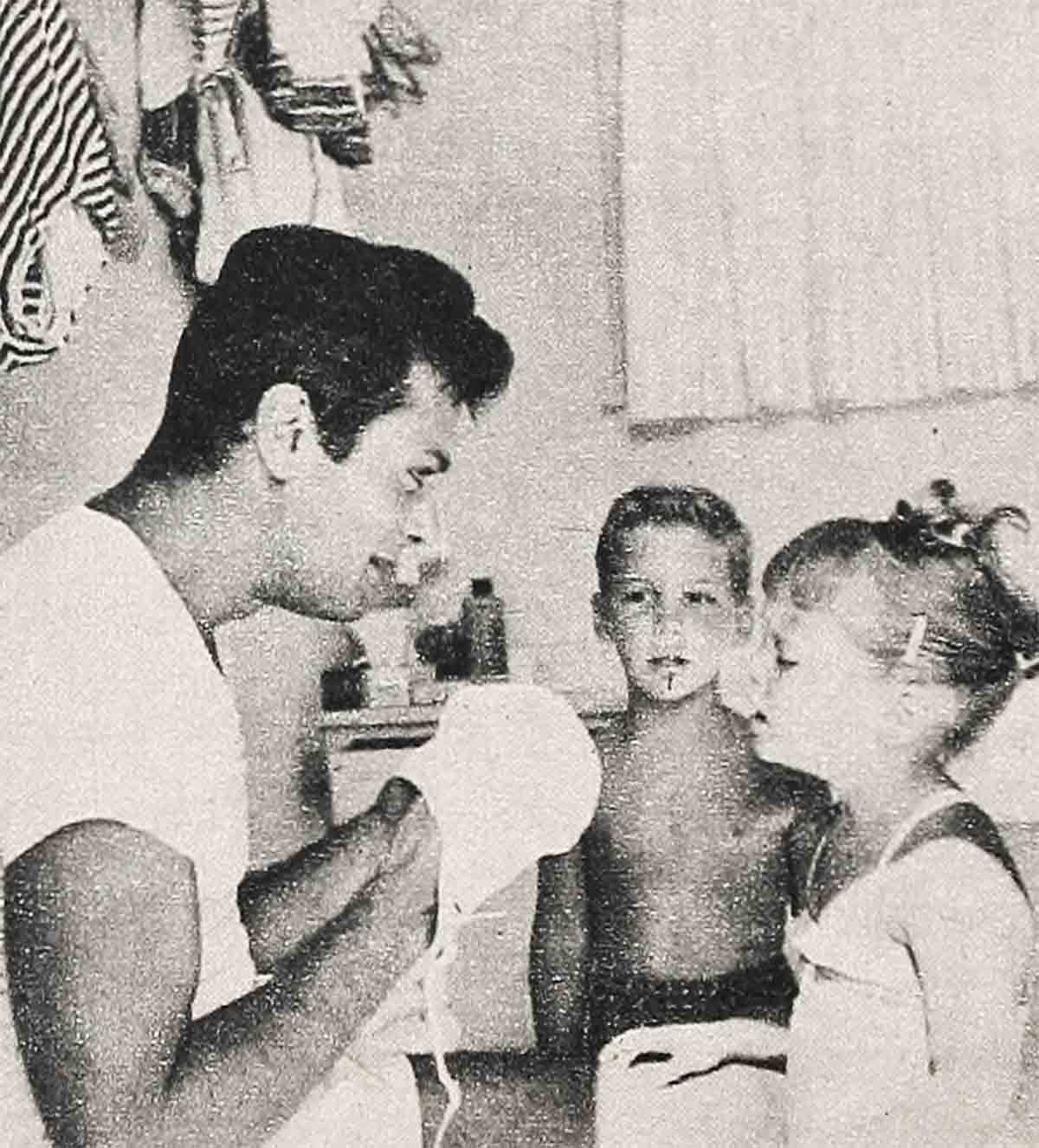

Papa Tony Curtis

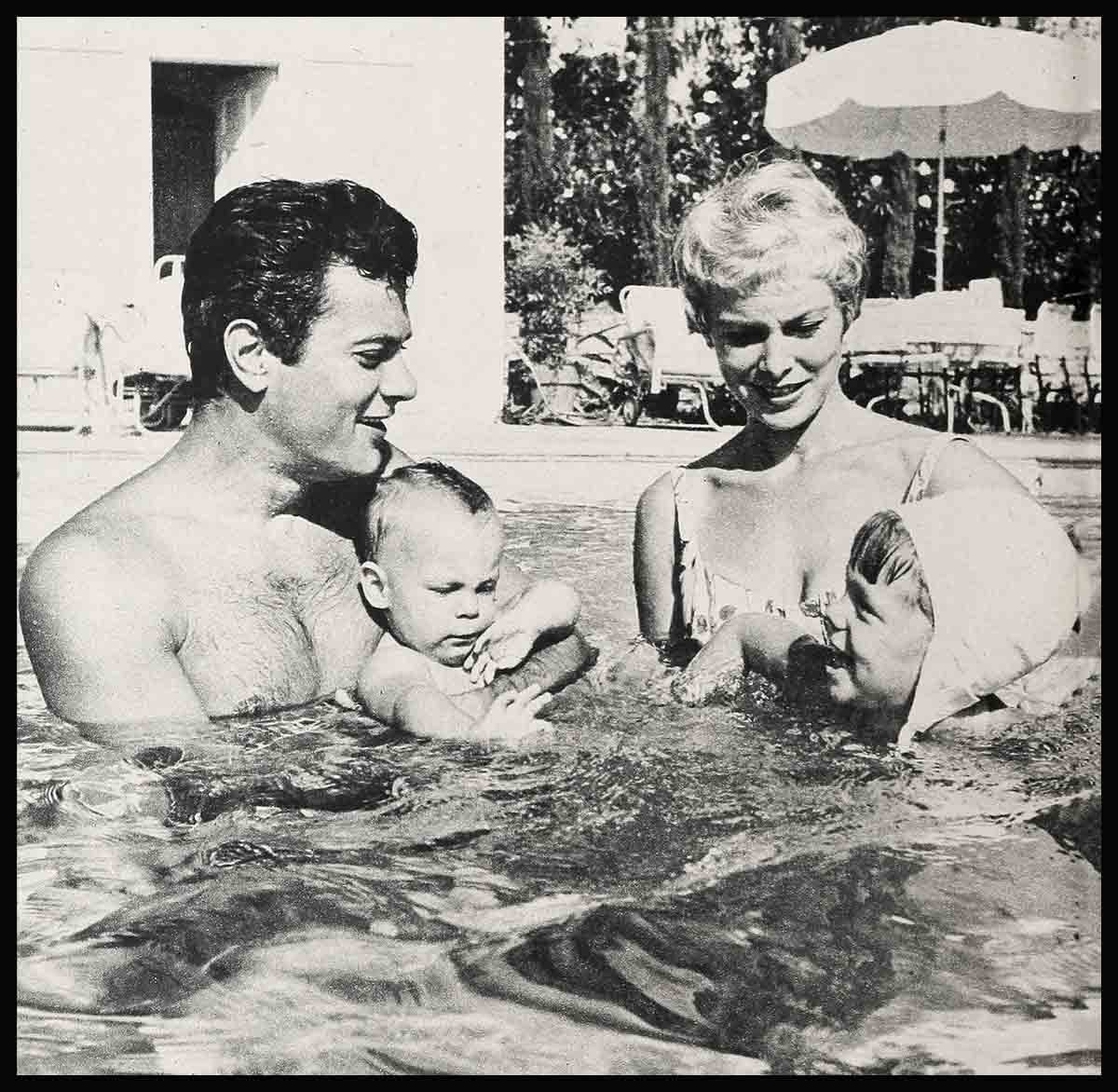

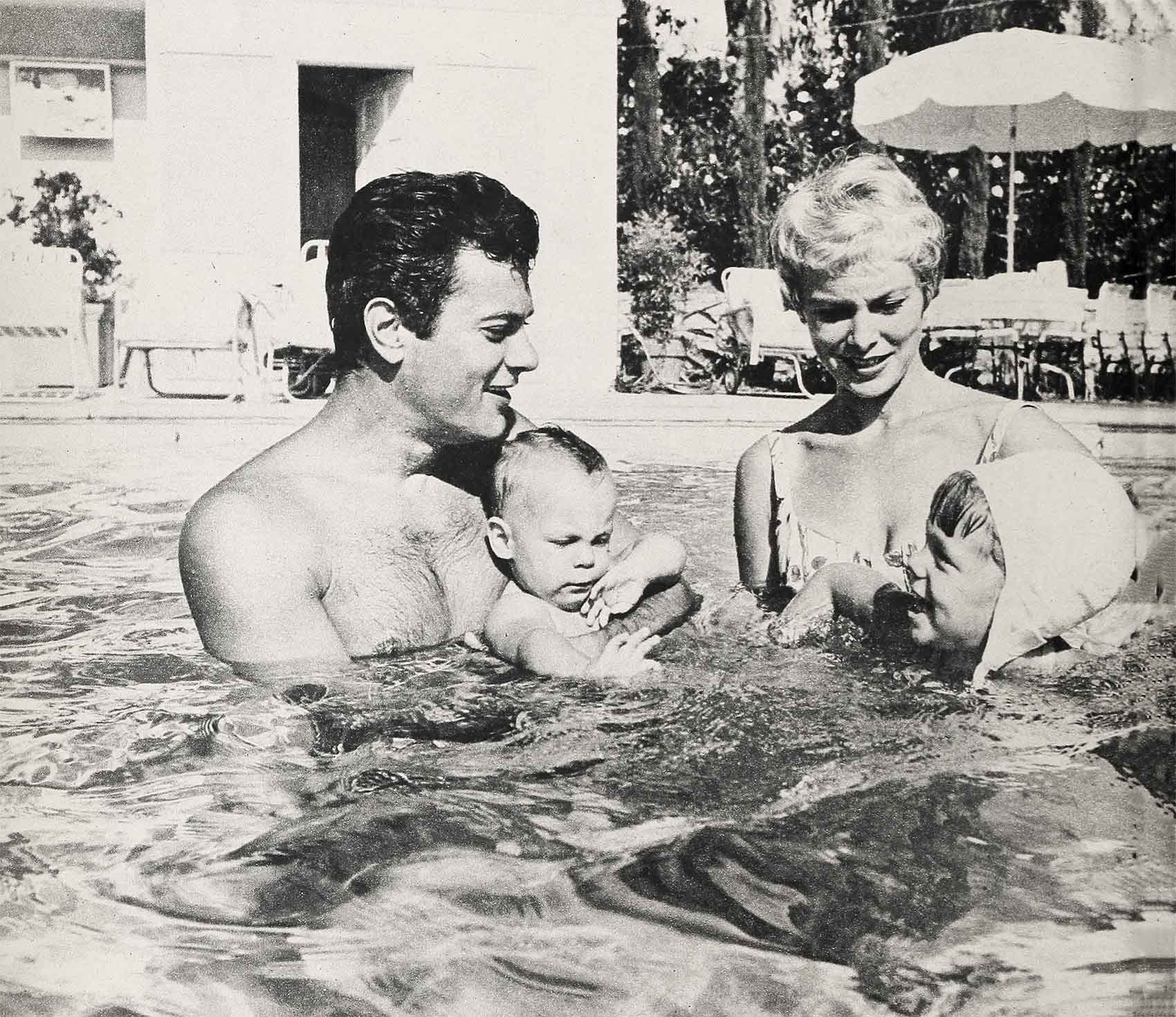

I doubt that in all the history of fatherdom any proud daddy has taken more pictures of his children—and in more farflung corners of the world and from more odd positions—than my husband has. To watch Tony follow our daughters, three-year-old Kelly Lee and one-year-old Jamie, with cameras dangling from all sides of him, he looks like a fugitive from a Rube Goldberg cartoon.

There isn’t a mood or a phase in their development that Tony hasn’t captured on film—the first step, the first tooth, the first haircut, the first diaper change, the first spoonful of food, the first dress. He’s taken jillions of pictures of them. No matter where Tony is making a movie, the walls of his dressing room are fairly papered with snapshots of the babies. We have literally hundreds of albums downstairs in our house.

Yet Tony is not one of those fathers who badgers his friends, whips out his wallet, and insists that they exclaim over the latest snapshots of his offspring.

Not that he wouldn’t. It’s simply that he never carries a wallet, so he has no way of keeping pictures of Kelly and Jamie on his person.

However, that doesn’t mean Tony’s friends are safe from his paternal pride. He buttonholes them with something even better than pictures. He stops them on the street, beards them in their offices, grabs them on the set, and sometimes even calls them long distance to announce with tears of laughter:

“Wait till you hear what Kelly did this time!”

Everything she says gets reported to everybody. Anything she does everybody knows. Tony goes so wild over some of her exploits that he tells them again and again. One that still breaks him up every time he relates it concerns the time he was lying on the couch in the den, watching television, and Kelly romped into the room.

Tony had had a hard day at the studio, and he was tired. As far as he was concerned, little Kelly couldn’t have picked a more touching moment to come over to him, as she did, run her hand soothingly over his face, and say, “Close your eyes, Daddy, and rest.”

He was all choked up. He thought it such a tender gesture for a three-year-old child, so giving. Of course, being putty in Kelly’s hands at any time, Tony did as she bade.

It was only because he was so overcome with affection that he cheated a little and peeked out of the corner of one eye. If he hadn’t he would have missed out on one of the thrills of his life. You see, although on occasion it takes great effort, Tony tries conscientiously to cooperate with me in enforcing various house rules with the children. Kelly can twist him around her little finger, and Tony loves being twisted. But he’s also adult enough to realize that certain prohibitions, painful as he may find them to impose, are for Kelly’s benefit.

This is all by way of saying that Kelly knows she is not to have any candy or nuts unless she gets permission. Consent usually is forthcoming unless she hasn’t had her dinner. On this occasion, Kelly’s craving came before dinner, and she knew that if she asked Daddy, he’d make her wait.

So she looked at Tony again to make sure that his eyes were shut, and she tiptoed to the table where there was a jar of nuts. She quickly popped one in her mouth and swallowed it. Then, an expression of exquisite triumph on her face, she went back to the couch and shook Tony’s shoulder.

“Now you can wake up, Daddy,” she said. “Did you have a nice rest?”

Tony constantly regales people with his adventures in fatherhood. He not only enjoys being with his children. His greatest pleasure is to talk about them—not in terms of how precocious they are, but in terms of what a joy they are to him, in terms of the never-ending wonder of childhood as seen through the eyes of a warm and loving daddy.

He whoops with delight every time Kelly tosses off another bon mot. She came home from the dentist’s office the other morning, for example, and reported proudly that by official count she now had 20 teeth.

“Twenty teeth!” Tony cried. “What are you going to do with all those teeth?”

“You’re going to eat with them, aren’t you dear?” I said.

“Yes, Mommy,” she smiled. “I’m going to eat with them.”

A second later she was shaking her little head vigorously.

“Oh no, Mommy,” she corrected herself. “I’m not going to eat with them. I chew with my teeth. I eat with a fork.”

The same morning Kelly asked my mother if she would read to her. Mother was happy to oblige. A few minutes later I called out to ask Kelly how she was getting along.

“Oh, just fine, Mommy,” she chirped brightly. “I’m helping grandma read.”

And don’t you know that Tony spent the rest of the day, practically, on the telephone circulating those stories all over Hollywood?

He is so sentimental about the children. Every time they blink an eye, almost, he feels it ought to be preserved as a great moment in history. Kelly’s baby book is full of cherished heirlooms collected by Tony, and now, with undiminished enthusiasm, he’s doing the same with Jamie.

When Kelly was six months old, she made her first scribble other than a straight line. Tony has kept that drawing as if it were a Van Gogh. He put her first lock of hair in an envelope and kept it in his dresser drawer for years before he transferred it to the baby book. While we were in Europe, Orlando Martins, the wonderful Negro actor who was in my picture, “Safari”, gave Kelly a large copper coin—the first he’d ever received. Tony has that, too, in safekeeping for posterity within the covers of her baby book.

Tony gets so carried away. He often makes his own entries in the white leather-bound documentary and pictorial record of Kelly’s development. With a sense of history that only a doting father could be capable of, he made the following inscription:

“Saturday, August 11, 1956, exactly at 5:43 and 40 seconds, Kelly smiled at me and Janet and Jerry and Helen and Manny and Bobby.”

Jerry is our friend, Jerry Gershon. Helen and Manny are Tony’s parents, and Bobby is his younger brother.

Tony is such a partisan father that he doesn’t even hesitate to tamper with official records. On a certificate of identification marks, there was a blank space next to the designation, “Shape of Head”. Tony wrote, “Beautiful!” Also in the book is Kelly’s first Medical Examination Certificate. Where it called for a description of her condition, the doctor had written, “Good”. Tony crossed that out and substituted a word he thought more appropriate, “Excellent”.

Kelly just had an operation for the removal of a double hernia. Believe you me, it was a lot harder on poor Tony than it was on Kelly. He was a wreck. Jamie had had the same operation, so Tony had been through it all before. But if you think that made it any easier for him, you just don’t know Tony.

Besides, Jamie was not a real person to him yet. She was only 13 days old, and it takes a Daddy a little time to grasp the fact that such a brand new baby actually is a person. It’s not like a mother who carries the baby and feels the baby inside. And Kelly is so much a part of Tony’s life. They adore each other. Tony just dissolves when Kelly says, “I love you, Daddy.”

He couldn’t bear the thought of this happening to her. He would leave the room whenever the doctor was examining her. He would go for a walk. He would get a magazine and not read it. He would sit for a minute, and then pace.

Kelly was in the hospital two nights. I slept in the same room with her the first night, and Tony spent the night in the doctors’ quarters upstairs. You’ll notice I didn’t say he slept there. He couldn’t sleep. Every ten minutes or so he would get up, and come down to our room to make sure that everything was all right.

On the second day he went home only long enough to change clothes and to play with Jamie before her bedtime. He spent the night at Harold Mirisch’s house. He just couldn’t come home with me not there, and Kelly not there.

When Kelly went in for her operation, Tony tried to talk, but he just couldn’t. Pretty soon it was over, and she was all right. Tony acted like the one who had been under an anesthetic. The shock of relief was so great that he couldn’t move. He was just numb. A couple of good night’s sleep, though, and he started to be his old self again—with all that wonderful aliveness he has.

It’s only natural that anyone capable of such love would be subject to great anxiety. If Tony has to be away from home any longer than two weeks, he insists that the family come along. But no matter how briefly he is gone, he worries. No matter what he’s doing, no matter what else is on his mind, he has to call the house at least four or five times a day to make sure personally that everything is all right.

I couldn’t join him until a week later, so when he went to Florida on location for “Operation Petticoat”, he had to leave by himself. I knew where he was every mile en route. I kept getting collect calls from every whistle stop between Los Angeles and Miami.

“How is everything?” he would ask. He was particularly concerned because Kelly had caught cold. “Is she better? Is she all right? How is Jamie? Are you all right? You’re not too tired or nervous, are you? That’s fine. That’s wonderful. I love you. I love you all.”

Some of our friends wonder why I don’t make a big joke of Tony’s worry streak. I couldn’t. I wouldn’t. It’s too real with him. I reassure him. Then he’s fine.

He’s certainly one of the most caring fathers I’ve seen around. One. thing I don’t have to worry about is Tony not wanting to spend time with the children. There’s nothing he loves better. He can’t wait to get home to be with them. He drops his things in his room. He says hello to me, and kisses me, and he’s off to find the kids.

Tony is so much. at ease with them. So many men seem lost with children. Most men don’t know what to do with them. Not Tony. Tony is not inhibited by children. He always has had such a wonderful way with them. This goes for any children, not only his own. They all love him.

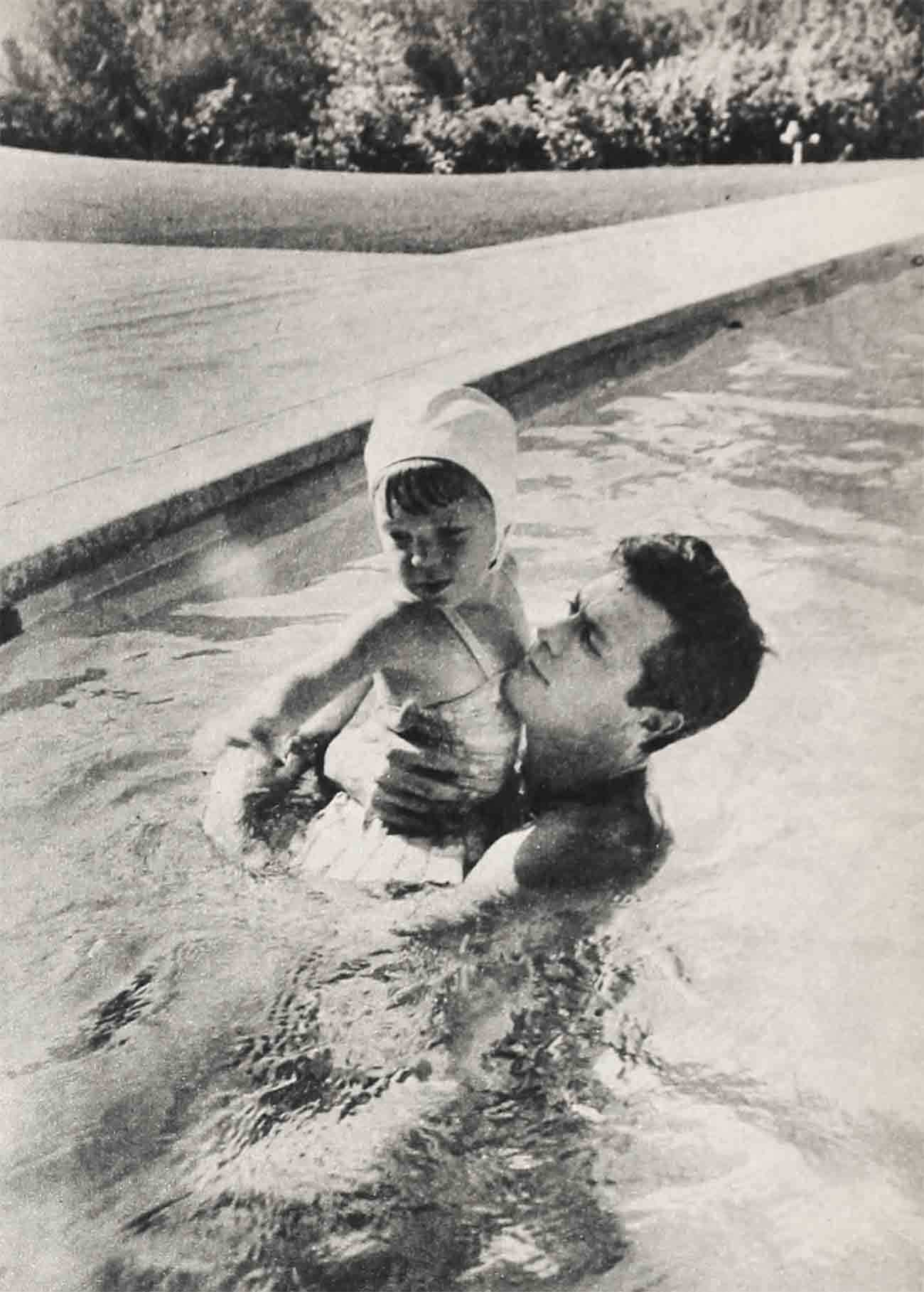

Part of it may be due to the fact that Tony was 15 when his brother, Bobby, was born, and he helped take care of him. When Kelly was an infant, Tony was better with her than I was. I’ve never had any brothers or sisters or cousins. I never was around newborn children. It didn’t take me long to learn, of course, but it sure was a comfort to have a husband who knew his way around a diaper, and who wasn’t afraid to hold a baby in his arms.

Nothing involving the children is a chore to Tony. When Jamie was born, his biggest treat was to change her, burp her, hold her and give her a bath. He adores playing with Jamie, and vice versa. Her big blue eyes go wider and wider, and she’s overcome with delight every time she sees her daddy. He throws her up in the air, goes ga-ga with her, and all that kind of stuff.

But not to hear Tony tell it. He says the trouble with the rest of us is that we just don’t understand Jamie’s language. He talks with her practically by the hour. He spouts his frightening gibberish at her, and she comes right back. They carry on the most incredible discussions that way.

Tony is such an imaginative, active and fun-loving father. Everything he does with the children is spontaneous and fresh. He plays a running game with Kelly in which he spins tales of a girl named Alice, who in reality is Kelly. Alice goes on imaginary trips all over the world. Tony tells about all the animals to be found in each country, and Kelly listens, entranced, or chimes in with observations from her own experiences when she was in Europe with us.

Tony razzle-dazzles her with card tricks, and makes her guess which hand the penny is in. Last night, he was in the kitchen baking cakes, and he made a game out of that, too. He used one of those squeeze things—oh, you know, one of those tubes of whipped cream or icing—and he drew all sorts of things on top of the cake for Kelly’s edification. She called for a flower, and he drew a flower. Then because we have mushrooms outside the house, he drew mushrooms.

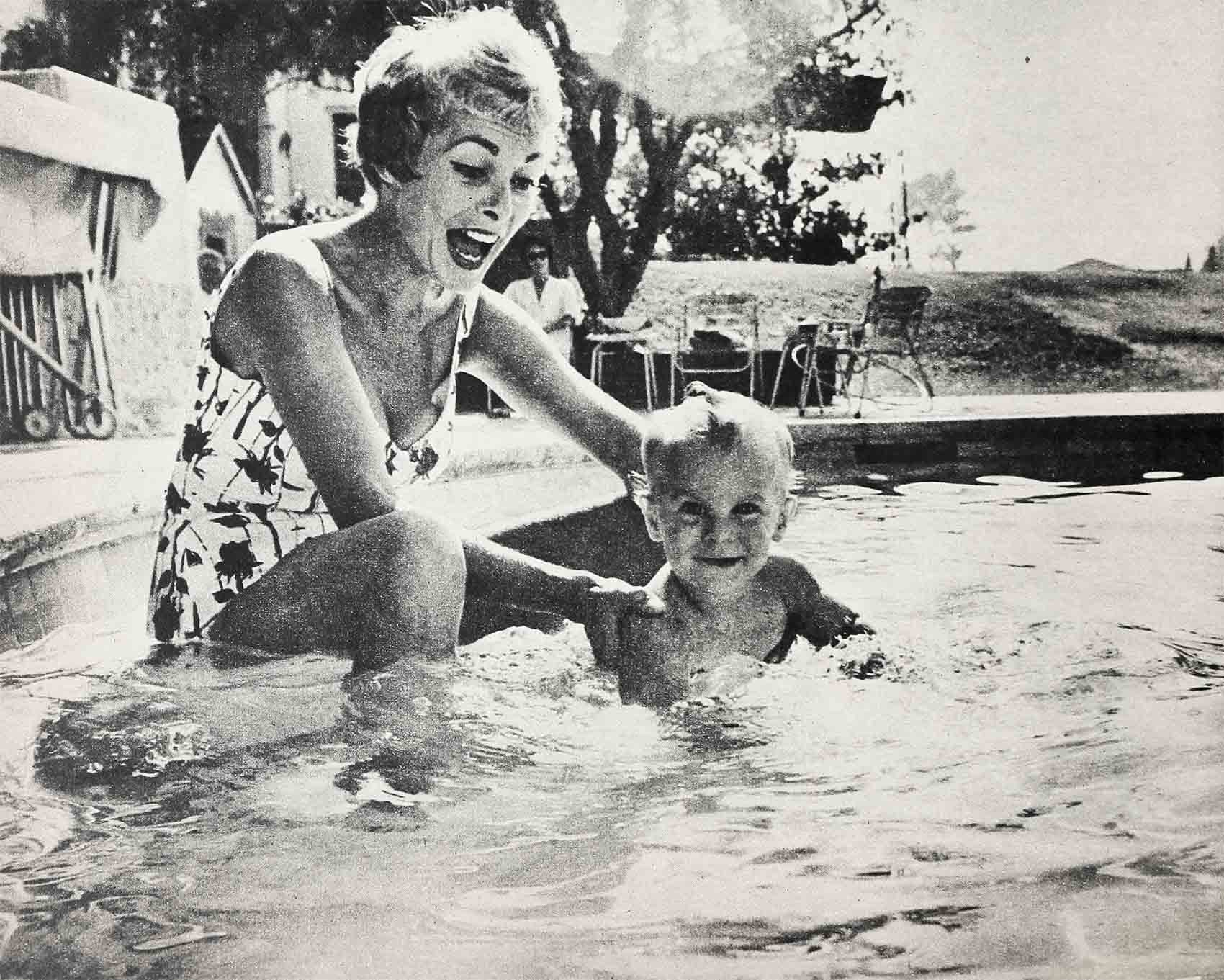

He makes everything fun. Kelly’s getting to be quite a swimmer, and Tony thinks up so many ways to help her overcome a child’s natural fear of going underwater. He throws her in the air in Superman games in which she is Super-lady. They hunt for their hands underwater. To quote a Hollywood cliche, they have a ball!

Of course it’s important that the children realize he is a parent, not a playmate. Tony recognizes this, so he gladly takes a hand in mundane things as well. He hears Kelly’s bedtime prayers, sees to it that she washes her face and hands, that she brushes her teéth, and he often bathes her. Yet even when he directs Kelly through these chores. it usually winds up with sounds of quaking laughter.

Kelly knows there are certain things she must do. She knows she can’t do or have everything she wants, and that she has to obey. Most important of all, however, she knows how much Tony and I love her. We are just as quick to praise as reprove her. Tony and I are thrilled with her sense of security. A few nights ago, to illustrate, Kelly did something very sweet.

“That was a very good girl, Kelly,” I complimented her.

“Oh,” she agreed matter-of-factly, “I’m a very nice person.”

Tony was so broken up that he had to run out of the room.

His rapport with the children is beautiful to behold. Kelly thinks of Tony constantly. If she does something well during the day, she says, “Will Daddy be pleased?” Toward evening she says, “Has Daddy come home yet? Is he still at work? Is he bringing home the bacon, Mommy? Is he bringing me home a little money too?”

No one needs to tell Tony how priceless the children are. So often we’ll be talking about them, and he’ll say:

“I knew I loved you before, Janet. We had a wonderful life before the children came. Now with them, I just can’t imagine our life before, and I love you more than ever. It’s so much better now with the children. Sometimes I wonder how we could have been satisfied before.”

I wouldn’t know how to rate a father, I suppose. I wouldn’t know how to compare one father with other fathers. All I know is that I like the kind of father my husband is. On my report card I’d have to grade Tony Curtis as excellent.

I can only offer amen to what Kelly says, and to what I know Jamie in her baby way tries to say:

“I love you, Daddy.”

THE END

—BY JANET LEIGH

It is a quote. SCREENLAND MAGAZINE MAY 1960