The Girl With The Lavender Life—Kim Novak

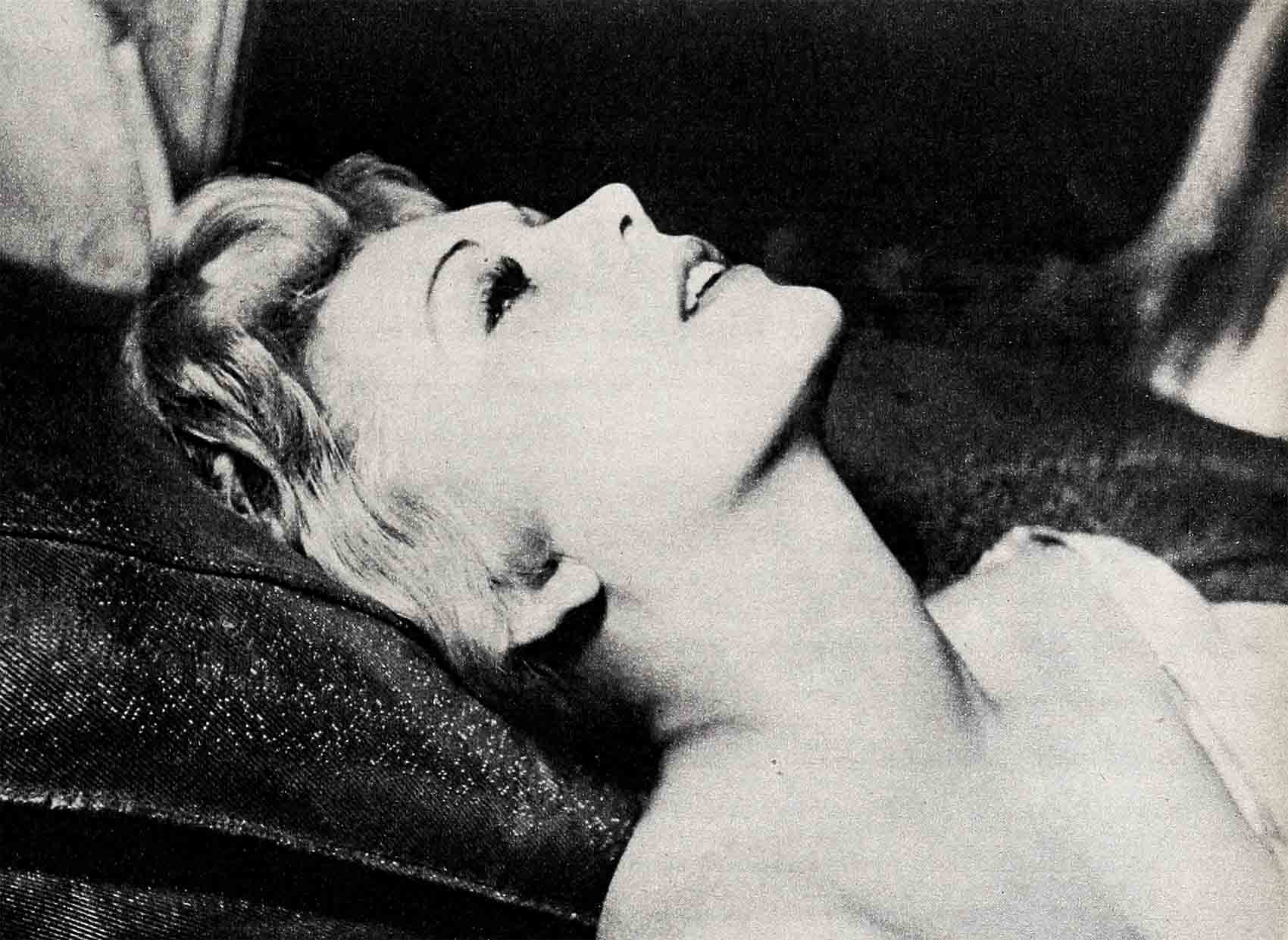

The girl between the lavender sheets with her ash-blonde head on a lavender pillow was not sleeping as well as she had been led to expect. There were noises. She sat up in bed, trying to draw what comfort she could from familiar lavender objects in unfamiliar surroundings, but in the darkness all lavender looked gray. There came a startling rustle from the dry palm fronds outside her window. “Man,” she exclaimed, clutching a sheet to her chin, “if this is fame and its so-called rewards, get me out of here.”

It was Kim Novak’s first night in her new apartment; her first night completely alone in her life.

The next morning the sun came through lavender curtains to glint on lavender walls, and all was right with the world. And the more Miss Novak thought about it, the more spectacularly right it was. This was her day, this morning of July 26th (automatically she noted that 26 was a double 13) and it marked an auspicious turning-point in her life. It was the day in which the girl who had become a movie star in spite of herself was to become a motion picture actress because of herself. There was a difference, and if to others it would not be strikingly noticeable, to Miss Novak it was enormous.

“I felt free, and I felt relaxed,” she recalls. “Why, I even felt grown-up, and about time, too, I’d say. I was twenty-three—there’s that number three again—I’d had a wonderful vacation in Europe, and now I was back in Hollywood in my own apartment. I don’t know how to describe it, but I wasn’t confused any more. I knew now that I wanted to be an actress.”

That Miss Novak should thus belatedly recognize her destiny was not so much a matter of indecisiveness on her part as it was an indication of the speed in which she had rocketed to the top. Not even Hollywood, grown accustomed to strange things, had ever seen anything like it. Contrary to all the rules of success as she or anyone else knew them, she had started at the top and gone up from there. Starring in six big pictures in two years, she had become a reigning Hollywood queen, an internationally famed beauty and the darling of the Cannes Film Festival while still thinking of herself as a misplaced fashion model.

Now she was the girl with the lavender life. Ahead of her were three more big pictures in sight, starting with the one in which she would play the role of Jeanne Eagels, the famed Broadway star of “Rain.” Around her were all her lavender possessions, some of which she could display for the first time. Even if the nights were lonesome and filled with strange noises, there was still one nice thing about having her own apartment. At least she had room to spread out.

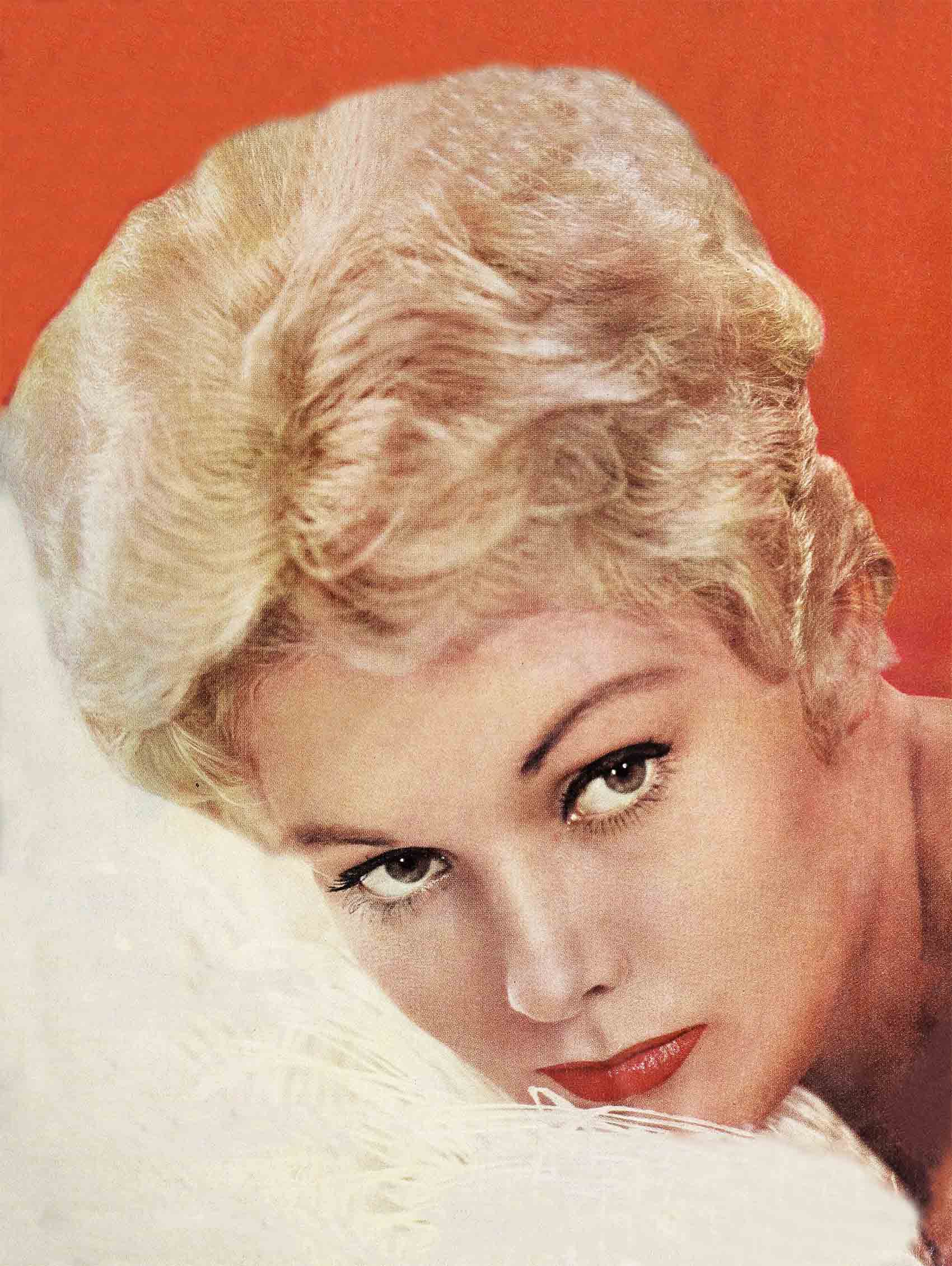

In Miss Novak’s life lavender has become an all-important morale-builder, lavender being her word to describe rather inclusively all shades ranging from rich purple to pale lilac. For the most part, her small objects like vases, Italian glassware, ashtrays, candlesticks, and even the candles are a deep purple, as richly hued as Malaga wine. The larger objects like curtains, sheets, table cloths, napkins, slip covers, porcelain fixtures and the walls themselves are of lighter hues, the somberness of the blue in purple yielding to the cheerful uplift of lilac and pink tones.

The same applies to her personal attire. Deep purple for her costume jewelry, of which she uses very little, often doing without even earrings. A purple sweater and gloves, a lighter purple scarf, and possibly a pale lavender parasol. On formal occasions, when she might sheath her regal figure in severe black, she will still give her spirits an added fillip by tinting her blond tresses with lavender or by sprinkling her hair with a few grains of crushed purple rhinestones.

Just when and how Miss Novak first discovered her pronounced preference for purple she does not know, and it is probably just as well. The Romans of 2,000 years ago could have explained it to her quite simply: “Either you are born to the purple or you are not.”

Modern psychologists favor a more complex theory. According to many, a preference for purple indicates a subconscious yearning for power, an inherited wish for the prerogatives of royalty possibly passed down by some royal ancestor.

However, there is no known royal ancestor in Miss Novak’s Polish-Czech background and West Chicago birthplace. If she nurtures a subconscious yearning for power, it has not become evident to anyone ever associated with her for as long as a minute. A friendlier, more cooperative star has never arrived on any studio lot. On the other hand, there can be no doubt about the secret strength she draws from lavender, both in color and scent.

By way of illustration, there has been only one time in her life in which lavender was threatened with the loss of some of its magic quality. That happened last spring in France. She had just finished her personal appearance at the Cannes Film Festival where, on the screen in “Picnic,” and on the avenue as “Mademoiselle Keem,” she had all but stolen the show. Now she was off on what was supposed to be a relaxing vacation tour. Placed at her disposal by Columbia Pictures was an enormous car driven by a courteous, English-speaking guide-chauffeur, and with her was her mentor-companion, Muriel Roberts. They came at last to Grasse, in the heart of the French perfume country.

“I would,” Miss Novak announced, “like to see how they make perfume. Especially lavender perfume.”

Though French perfume makers are intensely secretive about their processes and guard their formulas with their lives, for the blond queen of the Cannes festival there was no problem. A factory manager took the young tourists in tow, guiding them past banks of flowers from which women were stripping the petals. While the manager was explaining to them how only one drop of essence could be distilled from pounds of petals, the word was preceding them. “Mademoiselle Keem likes lavender.”

But of course. There was a flurry among the factory girls, and a few minutes later the deed was done. By the time Miss Novak and Miss Roberts returned to their car, it was a lavender gas chamber. Every inch of the vehicle had been sprayed, inside and out, not excluding the motor, with essence of lavender, an oil so potent that only a few drops are needed to scent a gallon of lavender water.

While the two girls tried to turn their gasps for air into gasps of delight for the benefit of their expectant audience, the mortified chauffeur drove away as rapidly as good manners would permit, but there was no escape. As the motor warmed up, the fumes from it became intense, and as the sun warmed up the body of the car, Miss Roberts feared to light a cigarette lest it ignite an explosion that would blow the roof off. Nor was that all.

“We took showers in the hotel,” Miss Novak says with a wince, “and not only did we still reek of lavender, but now the whole hotel reeked, too. We sent our clothes out to be cleaned, but that only made the whole cleaning plant smell of lavender. And the car! For the rest of the trip it not only perfumed us, but it perfumed all of our guests, some of them permanently, I’m afraid. As for our poor chauffeur, I wonder how he explained it all to his wife.”

That such an experience did not ruin forever Miss Novak’s appreciation of lavender is proof positive that her addiction is no affectation, but a deepseated and hardy thing. It is doubtful that Miss Novak’s eminence as a Hollywood queen, often compared to that of Lana Turner, Rita Hayworth and the late Jean Harlow, can be attributed to an energetic acquisition of lavender objects, but lavender and eminence have gone hand in hand. When she first arrived in Hollywood as a vacationing model, known variously as Miss Deep Freeze and Miss Ice Cubes of 1953, her authority over the color barely covered a small lavender monogram on a white handkerchief.

Had Miss Novak known what a furor her arrival in Hollywood was to create within a year, she might have felt compelled to keep an hour-by-hour diary. In the more than 2,000 press interviews she has had since, the question most frequently asked her is, “Didn’t Hollywood terrify you?” followed by, “How did you go about getting your first movie job?” These are routine questions asked of all successful movie stars, and Miss Novak answers them with an honesty that is almost blunt. But therein lies a cause for confusion; hers is not a routine story.

For instance: “Miss Novak, didn’t Hollywood terrify you?”

It was delightful. I had just completed a cross-country tour for Thor appliances. I was the model who specialized in demonstrating refrigerators. Another model, Peggy Dahl, and I had a whole week off before going back to Chicago. Do you know what we wanted to do in Hollywood? The only thing? We wanted to swim in the Beverly Hills Hotel pool. We stayed there a whole week with Peggy’s mother, and, like I say, it was wonderful.”

Or take the second question: “Miss Novak, how did you go about getting your first movie job?”

“Oh, I never did. I didn’t know the first thing about acting, or movie studios or anything like that. I was a model. If you want to get a job as a model, you just go to an agency and leave some pictures of yourself, and if they need your type they call you. That’s all I did. I wouldn’t know how to get a movie job. All I do now is worry about losing them.”

On the other hand, add this routine question: “Miss Novak, how do you like being a big movie star, famous all over the world?”

“It’s terrifying. They have me up there at the top playing opposite Fred MacMurray, or Jack Lemmon, or Frank Sinatra, or Tyrone Power, and the rest of the time I’m studying day and night trying to keep above the bottom of my acting classes. When I think of how little I know, and how much I have to learn—wow!”

She was not terrified by Hollywood, but she is terrified by Hollywood. She was not an actress, but she is an actress—one of the best; not only by current standards, but in keeping with the standards set by a long line of movie queens. She doesn’t know how to get a movie job, but she worries about losing them. She is the boxoffice attraction behind six films now comfortably passing the fifteen-million-dollar mark, and she is the student actress now learning how to act. No, routine answers to routine questions will not explain Miss Novak.

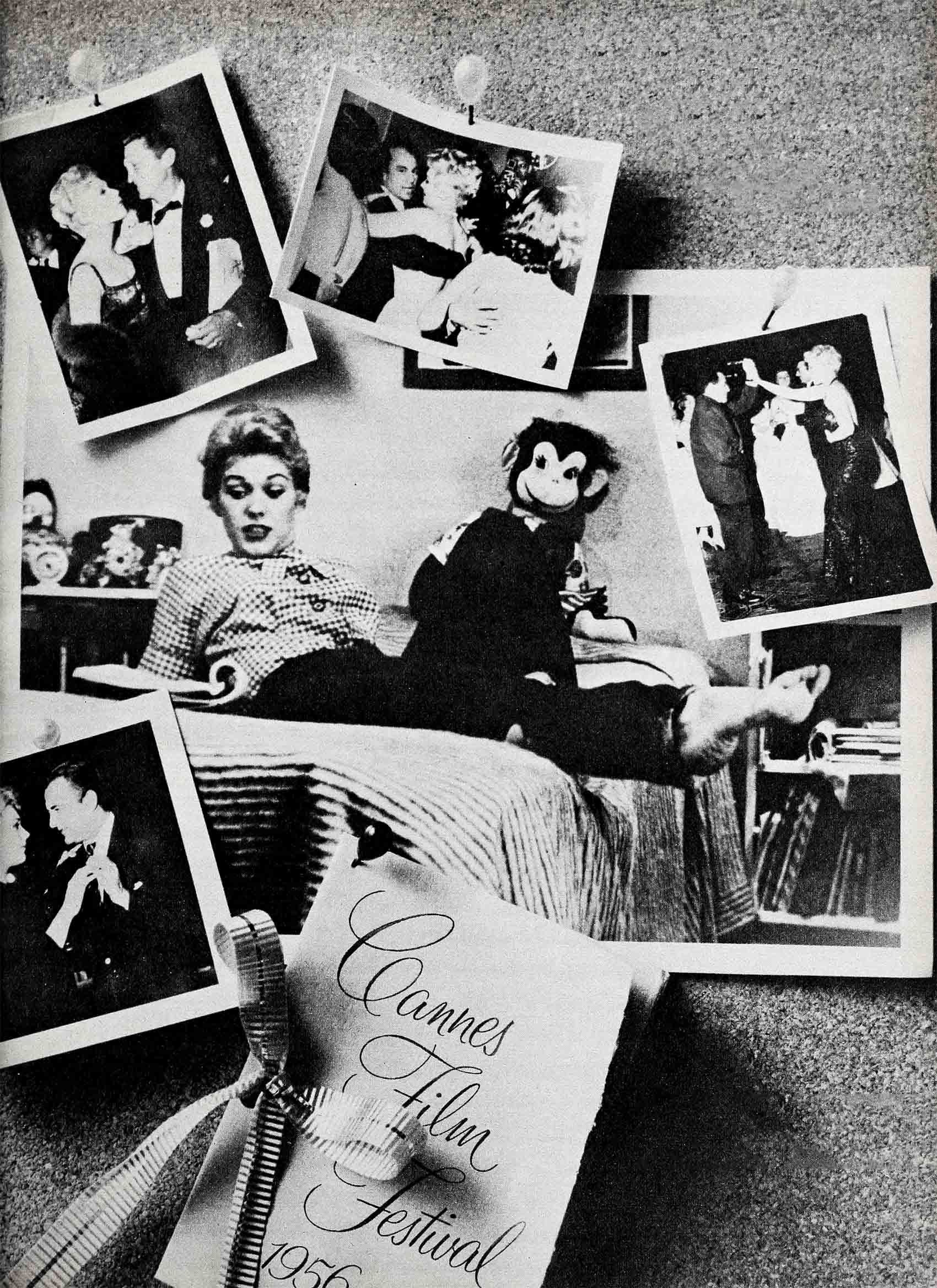

Kim’s Pin-Ups (clockwise from top left): Mac Krim, Prince Ali Khan, swinging it at Cannes, Count Mario Bandini.

Last August no less than sixteen influential magazines reaching all parts of the English-speaking world recorded the story of Miss Novak’s rise. All the stories bore a startling similarity, and for what can be considered a startling reason. They were true.

With relentless frankness Miss Novak outlined her career, adhering strictly to the truth and never deviating even for the sake of a good anecdote. She was told not to let the facts spoil a good.story. Instead, she leaned so far backward she let some poor stories spoil the good facts.

In brief, she was born in Chicago, educated in Chicago, and got as far as her second year in Wright Junior College before her interest in boys and the demands for her time as a model overcame her academic ambitions. She demonstrated refrigerators across the country, got a job as a model in Los Angeles, and it was as a model that she appeared in her first movie, “The French Line.” Then things began to happen.

As a proper Chicago girl who had once clerked in a five-and-ten-cent store, Miss Novak had moved into her first home in Hollywood. This was the Hollywood YWCA, otherwise known as the Studio Club, a congenial dormitory-sorority type of residence much favored by girls breaking into the movies. Rates were $19.50 a week, which included room and board. There she had the companionship her extrovert nature required; she had a choice of sports to work off her enormous energy; and she had long hours of talking shop with girls who had studied long and hard to make acting their career. As the girls chattered about what studio was hiring whom—a ballet dancer here, a coloratura soprano there, a girl to play piano in a Western barroom scene at still an- other—she quickly came to the conclusion that acting was not for her.

“I don’t believe in trying to fool myself,” she says, with her customary frankness. “I knew exactly what my acting limitations were. I could open a refrigerator door gracefully, and that was it, period. I could see where a lot of time might go by before any movie studio would want a girl to open an icebox.”

Serenely untroubled by the dedicated ambition that was driving her roommates to long hours of dramatic lessons, agonized breathing for tone control, tortured posturing for ballet and rehearsals for parts that seldom materialized, Miss Novak took her qualifications as a model to the Caroline Leonetti agency and immediately was comfortably employed as a clothes horse. By renting a bicycle to save cabfare she combined economy with exercise.

It follows, then, that the process through which she entered the motion-picture business was equally uncomplicated. One day RKO needed some models to back up Jane Russell in a luxury scene for “The French Line,” and the casting department, in an inspired moment, thought maybe real models might look more like models than actresses trained for the part. Kim Novak, the model, was hired to play Kim Novak, the model.

“I felt up to it,” she says with no false modesty. “It was a part I had been rehearsing for years, and I knew I could handle it.”

The camera has a sensitive and discriminating eye. It deals harshly with some, kindly with others, but with a highly select few it falls violently and inexplicably in love. To observers on the set, including the director, all the models went through their paces with equal poise and ease, Miss Novak along with the rest. But in the rushes it was Miss Novak, and Miss Novak only. The camera had chosen. It was a case of instantaneous love.

How agent Louis Schurr came into her life, closely followed—through still another lucky coincidence—by Harry Cohn, president of Columbia Pictures and by Max Arnow, the make-or-break man of the same company, has been told too often to need retelling here. Miss Novak pedalled home that night, found a phone message to call Arnow, and politely did so. She had, she was informed, an appointment for a screen test.

“I thought it was very nice of them,” she recalls now, and she is still painfully embarrassed at the recollection. “I knew how important it was to the girls around the Club when they were screen-testing for a special part, but I didn’t think of myself in that position. I thought it was like when you were a model—you know, drop around, leave some photographs, and ‘We’ll let you know if we can use you some day.’ I wasn’t screen-testing for a part. I was just screen-testing for—well, nothing.”

She arrived two hours late. More than forty people, including director Richard Quine, the late Bob Francis, the cameraman, the make-up crew, the script girl and assorted representatives of all the other arts and crafts that create a motion-picture scene had been waiting for her in various stages of patience or impatience. As the enormity of her offense dawned on her, she became more and more embarrassed and confused. When she was handed a scene from the Broadway play “The Moon Is Blue,” she could hardly hold it, let alone read it.

Bob Francis, the tall, handsome actor who showed so much promise before his tragic death, came to her rescue. Gently he ran through the lines with her, then kiddingly, and finally, when she began showing some response, seriously.

“Don’t worry about it,” he assured her. “Good lines make good actresses, and these are good lines. You can’t miss.”

But she could. “It was over my head. I was supposed to read a scene that Barbara Bel Geddes had made famous on Broadway, and I knew I wasn’t her. I didn’t know who I was, or what to do, and I was just terrible. If Bob hadn’t carried me through, I never would have finished. I just wanted to hide somewhere.” Her green eyes are -near tears at the recollection. “Poor Bob, he was so considerate.”

She was bad enough, but she couldn’t have been as bad as her tormented recollection leads her to believe. At least not to hear director Quine tell it.

“We needed a girl to play opposite Fred MacMurray in ‘Pushover,’ and we wanted somebody new,” is the way Dick explains it. “And Kim—she was Marilyn then—had something.” This was no doubt so, but this particular part called for a dramatic actress, and Miss Novak simply could not act.

Nevertheless, Dick, confronted with his first big picture and with his whole career at stake, persisted in his belief that Miss Novak was exactly what he wanted. It was a daring decision, and he won out. Miss Novak was notified by phone that she would start her acting career as a Star.

“You’re kidding,” she said flatly. Another ten minutes went into assuring her that she would indeed play opposite Fred MacMurray in “Pushover.” She remained unconvinced. “But it’s nice of you to say so, and I’ll come over tomorrow to see what part you really have for me.”

That night as the Studio Club girls gathered in the living room for their customary exchange of trade gossip, Miss Novak came out with her story of the “joke” Columbia was playing on her. There was a moment of shocked silence.

“Jokes like that they should play on me yet,” said one girl in her best Bronx accent. “Marilyn, you dope, don’t you know Columbia doesn’t play jokes like that? This is for real.”

Miss Novak listened in disbelief as the chatter rose to an uproar. When it finally dawned con her that the offer she had heard was to be taken seriously, her eyes brimmed with tears. Here were girls who had worked for years for the chance she was being given. They had worked on Broadway, on television, in bit parts, and some of them in supporting roles. They had studied dramatics, dancing, music, the whole realm of creative arts, and they were still awaiting “the big day.” And now she, the blond model whose one contribution to the drama was an ability to open an icebox, was being raised far over their heads. Her first reaction was that it wasn’t fair. They had worked so hard, and she had done nothing. She looked

around. There wasn’t a jealous eye in the crowd. Instead, everyone was delighted and encouraged. The magic wand had touched one of their number, and in so doing had restored to each one the belief that she was next.

“What a crowd,” sighs Miss Novak today, looking around the apartment in which she finds too much solitude. “No wonder I miss them.”

Stardom on her first picture was a torment that eliminated forever the possibility that Miss Novak might let her eminence go to her head. “I had never wanted a movie career,” she says firmly. “If I had, I would have studied for it, the same as everyone else. I was never even stage-struck. To be honest about it, when I went to Wright Junior College, I wasn’t interested in the dramatic club. I was interested in boys. So even when Columbia gave me a leading part, I didn’t know if I wanted to be an actress or not. I just thought of it as a lark, something to try so I could tell the kids about it when I got back to Chicago.”

Interrupting her story, she goes out into her lavender kitchen filled with bright new copperware, where she is checking out a new automatic grill. “It may be automatic,” she says, returning, “but you still have to cook hamburgers in the same old-fashioned way. Anyway, Fred MacMurray—what a darling—and Mr. Quine began to convince me that maybe I should take up acting as a career. Up to that point I had been thinking, ‘Just let me finish this picture, and never again.’ Now I began to think, ‘Now you really want to be an actress and look what you are doing—messing up the picture so you’ll never get another chance. Every night I went home thinking that I’d be fired the next day. Do you think that was fun?”

She had good reason to feel as she did. She flubbed scene after scene, and she knew it as well as anyone. Yet when she did knock off a take, Dick felt more than rewarded for the extra film he was using up.

Then came the critical point. In transoceanic aerial navigation it is known as “the point of no return,” meaning that point in the journey in which the aircraft no longer has enough gasoline to return, but must go ahead to the opposite shore. In Dick’s case it came when he had so much money invested in the film he could no longer substitute another leading lady, but had to finish with Miss Novak. And he was up against what appeared to be an insurmountable problem.

Kim still knew nothing about “the business” of acting, yet now she was going to have to act and no one could help her. She had to belt Fred on the jaw. That was all. Just haul off and belt him a good one.

The trouble was that friendly-as-a-puppy Miss Novak had never belted a man in her life, nor had she ever seen it done except in some half-forgotten movies. Furthermore, Fred was her good friend, the man who had helped her out of many a bad spot. Smack him a good one? She found it a physical impossibility.

But she tried. She got up a half swing, and a three-quarter swing, and finally managed to touch his cheek. Dick’s voice came booming, somewhat desperately, over the microphone. “The next one’s a take. All right, quiet everyone. Action! Roll it!” He watched tensely. The whole set watched tensely. Miss Novak swung from the floor, faltered midway, and finally connected with a weak smack. Fred withdrew his out-thrust, expectant jaw, and relaxed.

“I guess this calls for once more,” he said ruefully.

Not once more but a dozen more. And still there was nothing to print. Fred had been everywhere from one-quarter belted to seven-eighths belted, and his jaw was beginning to swell, but still there was nothing to show the public.

“Go ahead, hit me,” he pleaded. “Get it over with. This way you’re knocking me out by degrees.”

Along about the twentieth take a desperate and near-hysterical Kim reached for one, found it, and let it go with a smack that should go down in history. It actually rocked Fred back on his heels, and the cameraman nearly fell from his perch.

“Print it,” yelled Dick in high glee.

Miss Novak turned and fled from the set. She was inconsolable. No assurances from Dick or from Fred himself meant anything. Such statements as “You were great,” “You were terrific” and “It’s what we’ve been after all day” fell upon ears deafened by her own sobbing. She had slugged her good friend, and far harder than she had intended.

“But don’t you see, Marilyn,” said Fred. “That was your whole trouble. You didn’t intend to hit hard in the first place and that spoiled the picture. In this business, when the script calls for you to get slugged, you get slugged. Why, one time—” and he went on to relate the scores of instances in which he had been cold-conked by experts. Gradually Miss Novak’s sobbing subsided.

“But if this is acting,” she said at last, half defiantly, “I still don’t like it.”

It was a week before she could face Fred without apologizing all over again. And then she spent another week, after she realized the mental and physical torture she had put him through, apologizing for not having belted him a good one in the first place. Acting, she was learning, was a very confusing business.

In the meantime, the studio was beginning to realize that Dick Quine was developing a new and wondrously valuable piece of property in the girl who was still going under her christened name of Marilyn Novak. Possibly a million-dollar piece of property, in which case a proper name for the product was as essential as a good trade name for a new soap flake.

There were a lot of Marilyns in the business, dating back to the original Marilyn Miller, after whom another valuable piece of property over at 20th Century-Fox had just been renamed—another blond called Marilyn Monroe. The department-in-charge-of-names got busy. They found nothing wrong with Novak. It had a good, middle-European, somewhat Graustarkian ring to it; but the Marilyn had to go. They came up with three appellations, Kit, Lynn and Kim, but they could not come up with a final decision. Finally the entire studio was polled, and Kim, with an aptness not usually connected to a personality by an impersonal vote, won out overwhelmingly. Kim Novak she became.

What does she think about her new name? “I love it. Everything that has happened to me since I entered the movies is so new and different that it seems sort of fitting that I have a new name for it, too. Kim has a sound that sort of describes it. Not too fancy, and not too plain. Just about right, I’d say. I’m even beginning to think of myself as Kim.”

Every once in a while, though, she feels half-lost between the world of Kim and that of Marilyn Novak. “I call an old girlfriend on the phone, and do I say, ‘This is Kim Novak,’ or do I say, ‘This is Marilyn Novak’? If I say Kim I’m putting on airs like a movie star, and if I say Marilyn then I’m trying to be overly modest, because they know me now as Kim, and talk about me that way. It’s a real problem, believe me.”

In spite of her own and the studio’s satisfaction with the name of Kim Novak, it did enjoy one startling alteration recently. On the boat going to Europe, Miss Novak met Al Capp, the famous creator of Li’l Abner, and such enlightened communities as Dogpatch and Upper Slobovia. Capp was fascinated, to say the least, by the blond—slightly tinted with lavender— locks of the ravishing Miss Novak, and felt compelled to introduce her to his comic-strip readers. Lest she burst too suddenly upon them with all her sex appeal, he had her first appear enclosed to the eyes in a fur garment, and only reluctantly revealed her in all her glory. The name he pinned on her: Kim Goodnik.

Says Miss Novak with pleased resignation, “Well, there aren’t many who can tell their friends, in all honesty, ‘See you in the funny papers.’”

That Kim’s fame is not confined to her own home town or her own country was amply proved to her and to the world during that triumphal tour of Europe, where she danced with Ali Khan, captured the heart of the millionaire tomato king, Count Bandini, and started a small riot in Rome.

Leaving her hotel with her traveling companion, Muriel Roberts, she began to feel a little nervous as she watched the crowds collecting around her car on the Via Vittorio Veneto, which is to Rome what Fifth Avenue is to New York.

“Why are they all staring at me?” Kim asked Miss Roberts uncomfortably. “It must be because I’m a blond.”

“I doubt it,” said Miss Roberts, looking at the growing crowd. “It’s because you are Kim Novak.”

The crowd kept on growing until it filled the entire street and began blocking the side streets. Blue-caped, sword-carrying police tried frantically to cope with the jammed traffic, and ended at last by rerouting everything including the buses. Rome had seen nothing like it in many a year, and Miss Novak, her first alarm yielding to excited delight when she caught the spirit of the crowd’s friendly adulation, had never seen anything like it in her life.

The adventure left her awed if not completely overwhelmed. Everything was piling up on her so fast. “It’s too much,” she said. “Only a couple of years ago I was lying in my bed, crying my eyes out because of my first screen test. I wasn’t crying because I had flopped as an actress. I was crying because I had let down all those nice people. And now look what’s happened!”

Kim herself doesn’t really know what happened, because she is still in the labored process of catching up with her bewildered self. It has not been easy, nor does her future indicate that it will be any easier. Six pictures adding up to fifteen million dollars would be hard to absorb in any business. Rough and tough executives in steel or automobiles can only wish they could go before their rough and tough boards of directors with an asset like Kim. For a twenty-three-year-old, late of the five-and-dime, the accomplishment borders on dream-like fantasy.

What had she done, really, to deserve all this? And did she deserve it? For Miss Novak there was no interlude, no breathing period, no time to collect her thoughts and evaluate what was happening to her. She was moved into the major league without ever having played the minors. As she puts it, “They had me cast as a star, and I didn’t know enough to play an extra.” And when she says it, she is not running down extras.

No, when Kim makes a remark like that, her green eyes cloud over and the perfectly-profiled face looks thoughtful and more than thoughtful—a trifle uneasy. It’s the same kind of feeling she has when she talks about the reading kick she’s on, inspired by her discovery of Thomas Wolfe. Among other thought-provoking books, Mr. Wolfe wrote a fine story called You Can’t Go Home Again. By this he meant that there comes a time when people, while they may be able to go back physically to the home of their childhood, suddenly realize they can never again go back to the life they led as children.

That is what Kim was trying to say when, summing up the many and wonderful things that have happened to her in the past two years, she said:

“You know, I find a lot of that terribly true. I mean, not with my own home, my own family. I can always go home there and help with the laundry and the cooking, and help my sister Arlene with the diapers and things like that. But home, like when I call Chicago my home, has changed. Good gosh, I can’t walk along State Street any more like I used to. People stare at me and say, ‘There’s Kim Novak,’ and pretty soon I’m signing autographs. I like it and everything, but, gosh, my window-shopping has turned into a personal appearance. Sometimes I’d like to sink through the sidewalk.”

In her heart she still feels a little guilty. She doesn’t really think it’s right that all this should have happened to her and not to others who, she’s certain, are more deserving of such good fortune. She feels it as strongly today as she did two years ago, when of all those hardworking girls at the Studio Club it was she, Marilyn Novak, who was tapped on the shoulder for stardom.

But Marilyn Novak had that one tremendous, redeeming point that was to come to her salvation. It was what the camera saw, what Richard Quine saw, and a few others. It was a point she did not even suspect she had until, like everything else in her incredible life, she was called upon to produce it. And though she produced it in Hollywood, it was back in Chicago’s crowded West Side that it, like Kim herself, was born. It was the thing that was to take her to stardom and it’s the thing that will probably keep her there—in spite of anything she might do about it.

In next month’s installment you’ll meet the men in Kim’s life—from the boys she dated in Chicago to the millionaire Count Bandini—and find out what really makes Kim Novak the enigma she is.

THE END

—BY SCULLIN GEORGE

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE NOVEMBER 1956