He Stuck To His Guns—Guy Madison

It happened about a year ago—at the premiere of “The Charge at Feather River.” The applause was enormous, a sure indication that the picture was going to be a hit and its hero a star again. But one large, gray-haired woman in the audience didn’t take part in the clapping and the shouting. She sat in her seat, sobbing like a child.

During the past twelve years she had known, and believed in, the picture’s young star. She knew that for him there had been few ups and many, many downs, that it had been a long, hard road to tonight’s success. For Guy Madison, this was one of life’s rare moments of triumph.

Once before Guy had made a big splash only to fizzle out. He’d made his debut ten years earlier in a three-minute scene at a bowling alley in a tear-jerker called “Since You Went Away.” That scene drove bobby-soxers into hysterics and made Guy a star overnight. Supremely handsome, he became the nation’s number one pin-up boy.

The large motherly looking woman who sat sobbing in the audience that evening knew the story well. She was Helen Ainsworth, the woman who had discovered Guy and is his agent. “He looked so cute with his little sailor cap, I fell in love with him at first sight,” Miss Ainsworth relates, referring to the oft-told incident of how she discovered Guy in a picture on the back of a naval publication while she gulped down coffee at a drugstore counter. She got in touch with him by mail, persuaded him to visit her in Hollywood and saw him signed for a contract that same day. No doubt about it, Guy Madison—until then, Robert Ozell Moseley—was cute. But cuteness wasn’t enough. It didn’t wear well.

“I became a victim of my own publicity,” Guy comments on that phase of his career today. “The build-up was terrific. It made me into sort of a male Marilyn Monroe—only more so. The trouble was I had nothing to back it up.”

He’s still one of the handsomest men in Hollywood, but Guy Madison today is a far cry from the downy-cheeked sailor lad he was ten years ago. Nobody in his right mind would think of calling him “cute.” It takes a while, in fact, to find in his taut, virile features the faint echo of the tousle-headed youth he once was. It’s a man’s face now, a face full of character on which life has left its imprint.

“It took a little seasoning to bring it out, but Guy’s always had a strong spiritual quality,” Miss Ainsworth says about him in a more serious vein. “He couldn’t have held on through all those years if he hadn’t had character right from the start. What few people know about him is that he has strong religious faith. One of the men he admires most and has looked up to all his life is an uncle who went into the ministry and who is today a missionary.”

He himself is a little resentful at having the former Guy Madison dismissed too cavalierly. “It wasn’t my fault that I was young,” he protests. “What else was there to expect from a twenty-year-old kid fresh from Pumpkin Center, Cal.? It was like coming to fairyland—the fuss everybody made over me! One brief appearance in a film, and I was right at the top of the heap. And I didn’t know beans about acting. Naturally I promptly proceeded to slide down.”

Guy’s first picture after his release from the Navy was “Till the End of Time,” in which he was co-starred with Dorothy McGuire. Cruelly overshadowed, he looked stiff, awkward and self-conscious, and completely failed to come across. After that, his studio decided to loan him out instead of using him in its own productions. Guy’s reputation failed to improve, however. Nor did his performances.

“One of my bad failings was that I used to resent criticism,” he admits.

Guy didn’t know much about acting. It was quite the fashion to pan him. “Harvard, I think, once voted me the worst actor of the year,” he recalls. “It seemed almost like a conspiracy. After all, hadn’t I become a star with my very first picture?

“Altogether, I guess I must have been pretty full of myself in those days. Maybe I didn’t show it—I hope I didn’t—but you can’t have a bunch of teenagers go into convulsions over you and pretend not to notice it. It embarrassed me all right, but I won’t claim that it didn’t affect me to some extent. Deep down in my heart, I probably considered myself pretty hot.”

During his early days in Hollywood, Guy was shy and blushed easily, though. Once a famous beauty with an equally famous reputation cornered him at a party and asked him what he liked to do for his amusement and whether perchance he liked to play postoffice.

“No, Ma’am,” he replied, reddening to his ears. “I like to go rabbit-hunting.”

Maturity has since given him a lot more poise without taking away from his attractiveness. According to some of his associates, there’s rarely a female who doesn’t immediately shine up to Guy. During a recent personal-appearance tour with his tv partner and sidekick in the Wild Bill Hickok series, Andy Devine, a party of fifteen women raided his hotel room in New Orleans. They left hurriedly when Andy instead of Guy greeted them in bulging shorts. In Seattle a young mother pushed her son toward Guy. “You go and shake hands with Wild Bill,” she coaxed him.

“You go and shake hands with him yourself,” the offspring replied. “This was your idea.”

And in still another receiving line, a girl in her late teens squeezed through to the front of the crowd. “I bet my girl friend five dollars that I could kiss you,” she giggled, pursing her lips expectantly.

Guy looked her straight in the eye. “Lady,” he said, “I’m sorry but I’m afraid you just lost yourself five bucks.”

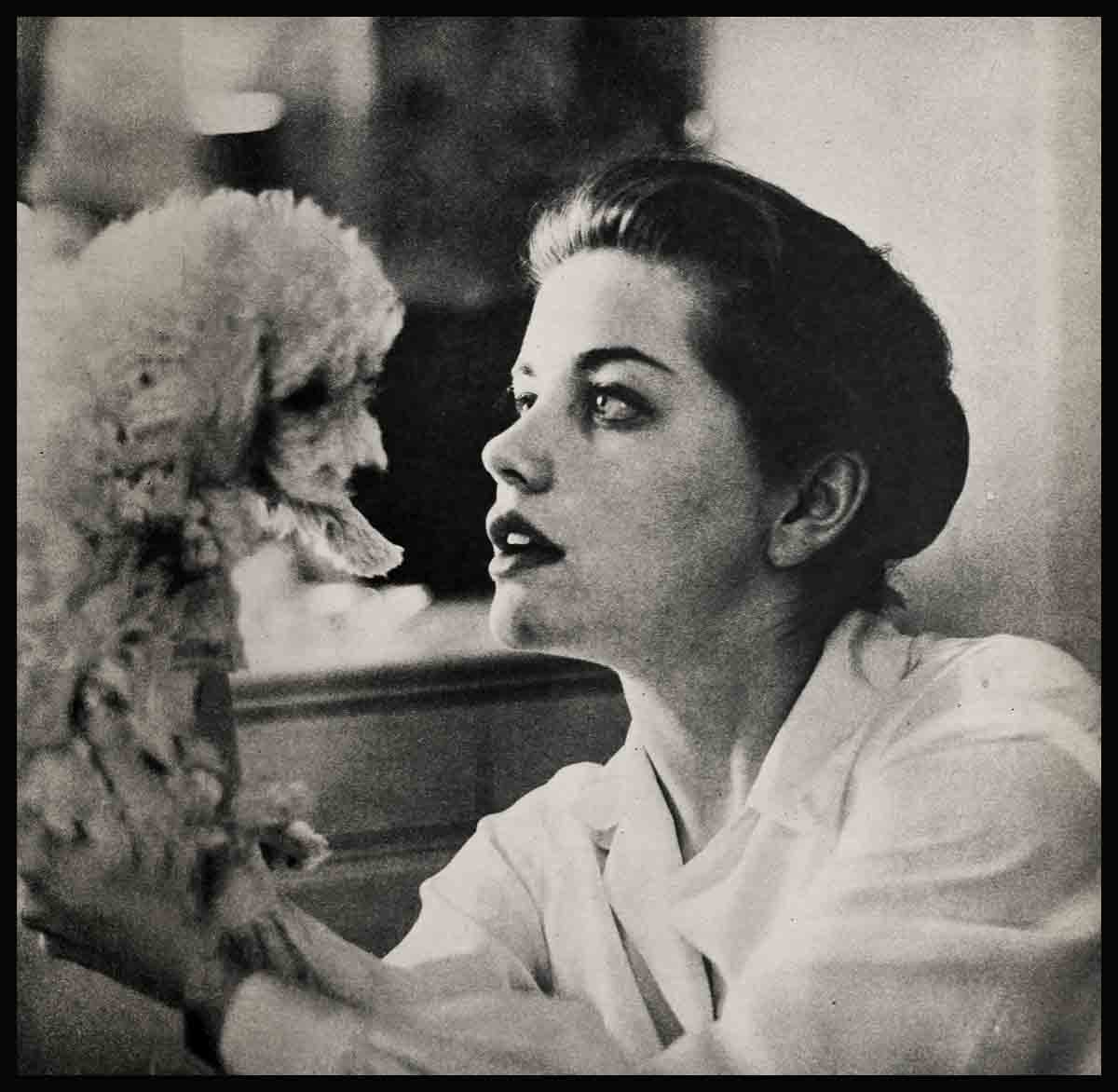

Despite his enormous mass appeal, he’s personally always been a one-woman man who doesn’t run around and scatter his affections. He did some experimental dating for a while, but fell in love with Gail Russell soon after he came to Hollywood, and for a long time Gail was the only girl in his life. He admits, however, that it hurt a little to see the admiring crowds and his popularity vanish. “There were a lot of years when nobody knew I existed,” he says. “I was still in my twenties and already a has-been. There’s one good thing about being on the skids, though. It gives you back your sense of proportions. There’s nothing like it to teach you the proper valuation of yourself.”

The years he refers to were the ones when Guy slipped back into oblivion almost as fast as he’d gone to the top—although with a lot less noise. They were Guy’s bad years in Hollywood. He wasn’t quite broke yet and he didn’t starve, but it wasn’t very funny all the same. Guy has a lot of pride, and disappointment with oneself is never very easy to take. Harder, though, a lot harder to bear than professional disillusionment, was the personal tragedy engulfing his young wife.

Guy is willing to talk candidly about almost anything else, but he refuses to discuss this phase of his life. He’s the kind of man who fights his battles alone and, during the years of prolonged crisis, even his closest friends had little direct insight into his mind or heart. His intense loyalty restrains him from making any but the most general comments to this day.

So much has already been written about the break-up of the marriage between Guy Madison and Gail Russell that the details needn’t be repeated here. Guy didn’t go into the marriage blindfolded. They were married in 1949 after he’d courted Gail for close to four years. He knew well that she was a sick girl then, abnormally shy and suffering from pro-found depressions. But he loved Gail and thought he could help her by giving her the security she lacked.

It didn’t work out. He had to stand by helplessly, watching an exquisitely beautiful and talented human being destroy herself.

He feels no rancor toward her. “Gail can have anything she needs and wants from me,” he was quoted only recently. He’s grateful for the honest emotion she let him experience and resents it when outsiders shift all the blame on Gail. “There are always two sides to every problem,” he insists. “I’m certainly not entirely free from guilt for the break-up myself.”

These—briefly—were the events that took the baby flesh off Guy’s face, and it was during these sad, unhappy years that he acquired the reputation of being something of a hermit who lived in seclusion, rarely went out into company and never was seen in a bar, at a night club, a gala premiere or a party. Guy was too strong to let heartache and disappointment break his spirit, but neither did it all simply run off his back. Suffering left its stamp on his face, refashioned him from the handsome young boy he once was into something rarer and infinitely more valuable—a man.

There is a stubborn streak in Guy that wouldn’t let him give up even during his darkest moments. While Gail, who’d been in many more pictures than Guy and had by far the bigger reputation, ceased struggling and eventually collapsed, Guy had a powerful drive to make good.

“In a left-handed way, being cut down to size somehow gave me more real confidence in myself than I had before,” he comments on that. “I remember how everybody used to tell me what to do and what not to do. I had to comb publicity people out of my hair. They told me to wear a tux, and I wore a tux. In my whole life I don’t think I’d ever even worn a tie before then. I was as uncomfortable as the dickens. The collar itched and kept sticking me in the back of the neck. But I was told to smile and I smiled. They told me to go to some party or another, and I went to the party. Always had a heck of a time trying to figure out what to do with all those knives and forks. Every move I made was dictated in advance. I felt as though I was smothering.

“I’m sure they meant well and did their best, but they tried to make me over completely and I just wasn’t the right material for them. Not that I wasn’t anxious to please. Too anxious perhaps. I figured I could put up with the acting business all right till I made myself enough money to buy a ranch and retire from pictures. Only it didn’t work that way.”

The turning point came when Guy began to realize that all those people who kept telling him what to do weren’t necessarily right. It gave him the confidence, at the very moment when he was hitting the skids at a rapidly accelerating pace, to rely on his own judgment.

Though his contract with Selznick assured him of pretty good eating money for some years to come, he secured his release from it, feeling that it was stifling him. He took drama lessons and joined a road company touring the country in “Light Up the Sky” and “John Loves Mary.” “It’s the old story that any job worth doing at all is worth doing well,” he says. “I’d never dreamed of becoming an actor before Helen Ainsworth tapped me on the shoulder, so to speak, but being in it I found that there was more to it than I’d thought. So I decided I might as well start learning my craft.”

Guy frankly concedes that he’ll probably never be a first-rate dramatic actor capable of portraying a wide range of different characters. Rather, he hopes to be considered a competent performer. “By that I mean that the part has to fit my own specifications instead of the other way around. ‘Be yourself!’ Eda Edson, my drama coach, told me that some years ago, and it turned out to be the best piece of advice anybody ever gave me. I’ve made that my yardstick by which I judge a new part. Can I, or can I not act naturally in it?”

When Guy was signed for his part in “The Command,” he read the script, sat down and wrote the producer a long letter. “I want to make it clear for the writer’s sake,” it started off, “that this script probably would be perfect for the type of actor he had in mind when he wrote it. But you’re stuck with me. It’s been my experience that to come across believably I have to be able to believe that I, personally, could act and react the same way as the character I’m playing.” This was followed by fifteen tightly written pages of specific suggestions. The kid from Pumpkin Center had indeed come a long way.

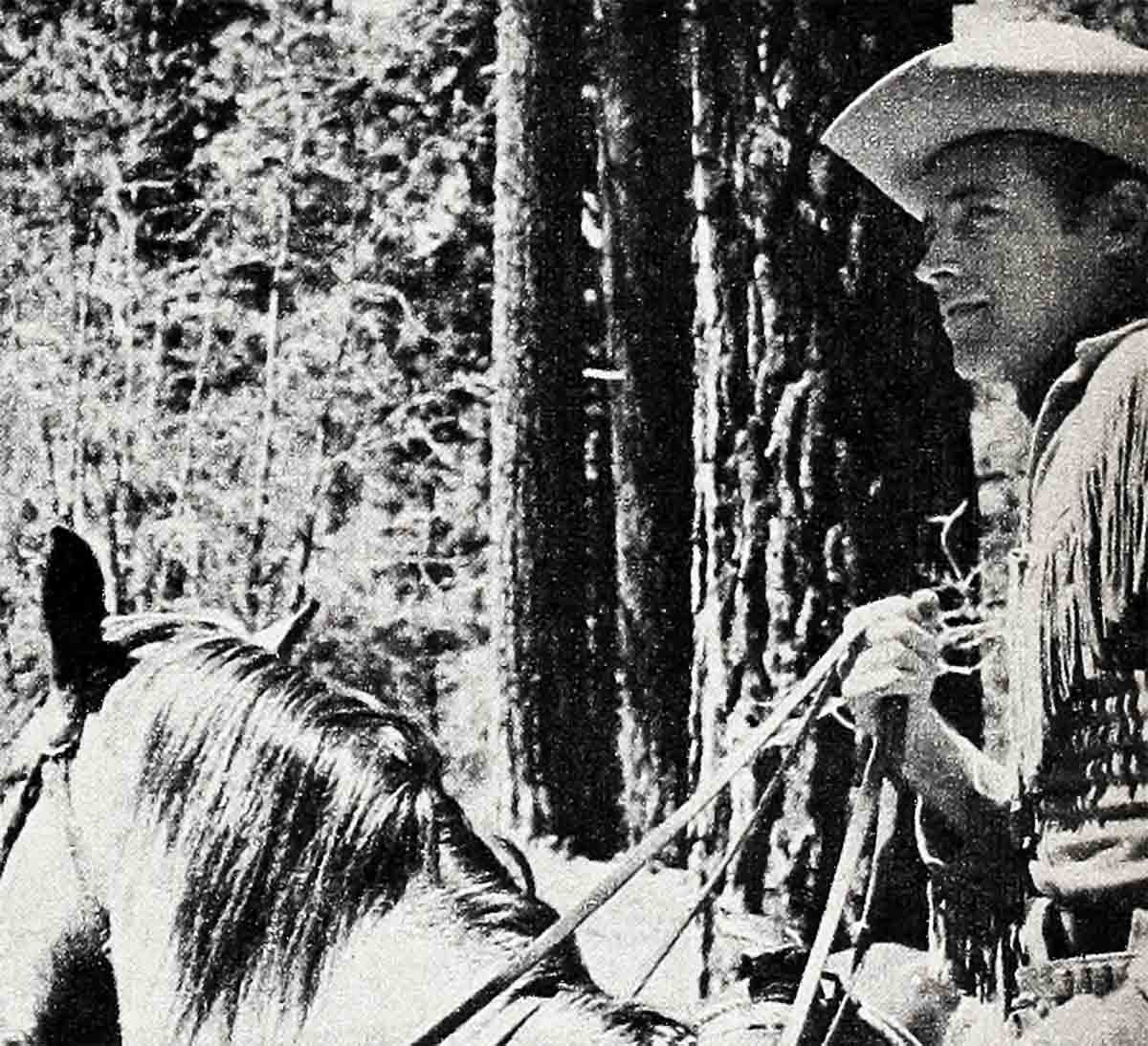

Few actors in Hollywood ever get a second chance, fewer still make the most of it. Paradoxically, Guy’s second entry into moviedom came about through his success on television where he’d portrayed the part of Wild Bill Hickok for some time. He’d been advised against taking it, but he liked the part and stuck by his guns. “For the first time since I came to Hollywood, I felt completely at ease from the minute we started shooting,” he says.

As a cowboy star he quickly became the idol of millions of youngsters. Kids can spot a phony any time, and they knew that Guy was the McCoy. It was one of them, Susan Trilling, eleven-year-old daughter of Warner executive Steve Trilling, who was directly responsible for bringing Guy back to the movie screen. She happened to overhear her father complain at the dinner table that he had a hard time finding a star for a picture his company was about to produce. “Why don’t you get Wild Bill?” she suggested.

Trilling listened to his daughter, borrowed a reel of the series and had it run off for Jack Warner and himself. “Get him,” was all Warner said when the lights went on.

The picture for which he was signed without a screen test after years of oblivion in Hollywood was “The Charge at Feather River,” one of the big hits of 1953. It re-established Guy as a star.

Ironically, the sharp up-beat in Guy’s career coincided with what was perhaps the lowest point in his private life. He and Gail had finally separated for good; he’d left their Brentwood home and moved into a small Westwood apartment, furnishing it with the barest necessities. The austerity of his quarters—he had to sit on the living-room floor to watch television—seemed to underscore his personal unhappiness and withdrawal from the world. He looked drawn and his friends seriously worried about his health.

Guy threw himself into his work. When the first rushes came in, the director excitedly ordered the script to be rewritten to give Guy a more important part. Helen Ainsworth, sobbing at the premiere, wasn’t fooling herself. She’d been in this business too long and had seen too many disappointments for that. She knew that this was the pay-off. Guy was in—and this time for keeps.

He has since scored in “The Command” and recently signed a long-term contract with 20th Century-Fox, for whom he’ll do “The Tall Men” with Clark Gable later this year. First, though, he must finish “Five Against the House” for another studio. He gets excited as he talks about that picture. “It’s about five ex-GI’s at college who hold up a gambling house. I’m one of the five, getting involved in it through no fault of my own. It’s a story with an unusual twist, a good story, I think. And I like my part.”

In addition to these two pictures, Guy will tape some eighty radio shows and do a score of television films in the Wild Bill Hickok series during the year.

Guy still wants to buy himself that ranch some day, but he’s no longer in too big a hurry for it. “It will have to wait,” he says. “I’ve got a job to do and I’ve come to like it. I don’t mind sticking around for a while.”

Proof that he’s serious about that is the fact that he’s building himself a house on Mulbolland Drive. “I picked a beautiful site with a terrific view over Beverly Hills on the one side and the Valley on the other. It’s not going to be a big affair, but a comfortable house with a swimming pool and a big workroom.”

There’s a good deal of pride in his voice as he talks about the house. Certainly he doesn’t sound like a man who has soured on life. Since buying a home usually means that a man intends to settle down in more ways than one, the question prompted itself as to whether or not he plans to get married again soon.

Guy may have seen the light of day on a farm, but he has the instincts of a gentleman to the manor born. “You shouldn’t have asked me that,” he scowled. “After all, I’m not even divorced yet. I’d be kind of a heel if I were to talk about any of that at this point. Sure I’ll want to get married again—some time.”

There’s been a normal amount of gossip linking Guy to a number of pretty girls, but he’s denied romantic involvement with any of them. It seems unlikely, however, that he’ll stay single for long after his divorce becomes final. He’s been separated from Gail for quite a while, is young, successful and, as noted, exceedingly attractive. And there are other indications as well that he’s no longer a recluse.

For instance, he’s recently bought himself a new tuxedo. Yes, Bob Moseley from Pumpkin Center, who used to squirm when he had to wear a tie, voluntarily went out and ordered a new tux. “The one I had was all out of style,” he explained. “It’s the one I got back in ’forty-six. It didn’t look right when I wore it at the premiere of Warners motion picture ‘The Command.’ ”

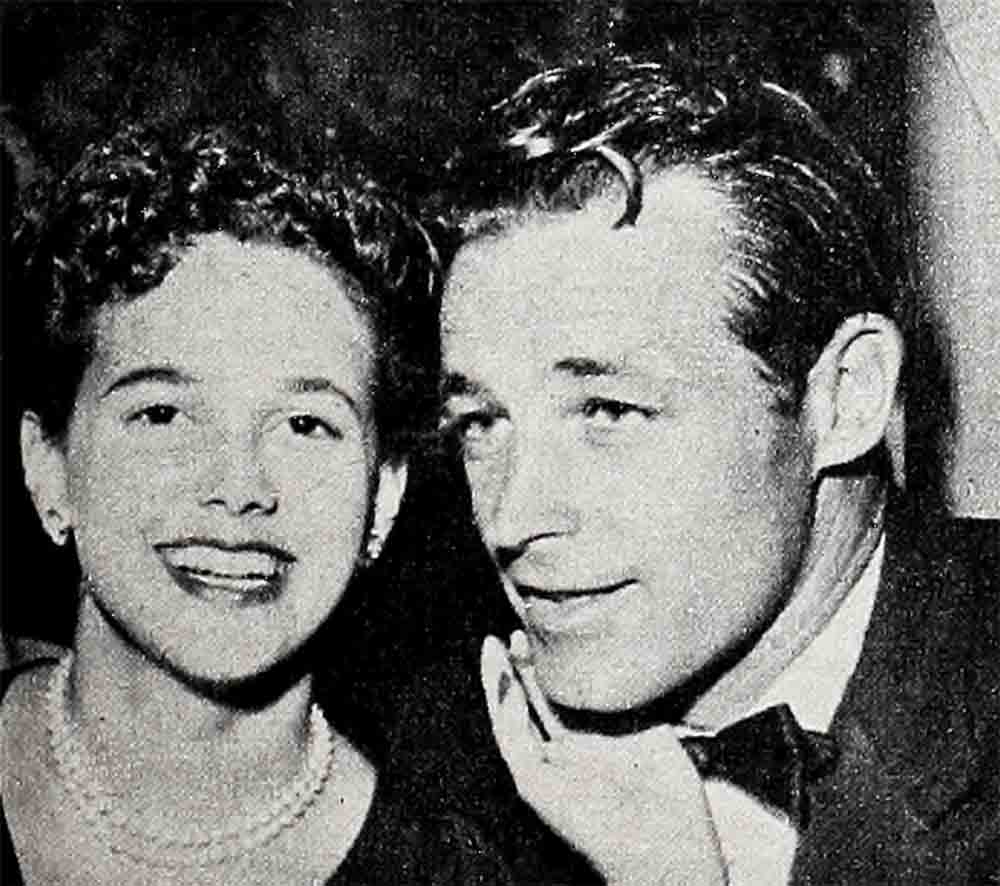

In years past you couldn’t have dragged Guy to a premiere. Being the star of the picture, he more or less had to be at the one for “The Command,” but he’s since gone to a lot of others. He wore the new tux for the first time at the premiere of “King Richard and the Crusaders,” and he didn’t go alone but asked Barbara Warner, Jack Warner’s daughter.

“Guy was worried about whether people would think he was buttering up the boss by taking out his daughter,” an associate of his commented. “I told him that was silly. For one thing, Barbara’s a real cute girl and is a lot of fun to be with. She can have all the dates she wants without trading on her father’s name. For another, Guy’s in a position today where he has to butter up nobody, and people know that.”

With an income estimated at a quarter of a million dollars a year, Guy Madison is indeed in an enviable position. Helen Ainsworth figures he’ll earn at least ten million dollars before he’s through, and the way he’s been going, that doesn’t seem to be such a wild guess. His contract for the Wild Bill Hickok television series calls for a percentage of the profits, and that alone, in addition to his radio and film earnings, is probably worth a small fortune. He’s only thirty-two and should easily be good for another twenty to twenty-five years of movie stardom in the type of roles he’s grown into. Guy’s manner is still unassuming, but he knows that he’s in a-strong bargaining position and the knowledge has given him poise and self-assurance.

One result is that after ten years in Hollywood he’s taking his place in the social life of the movie colony and no longer feels himself to be an outsider here. He joined the Lakeside Club about six months ago and took up golf, a sport that’s tame compared to hunting wild boars with bow and arrow, his favorite pastime since his early teens. “Howard likes the game, so I figured it must be all right,” he says, referring to his great friend and hunting companion Howard Hill, the world’s undisputed archery champion.

He’s also finally traded in the Ford pick-up truck which he drove the longest time for a snazzy Lincoln-Capri hard-top convertible. It isn’t the kind of car a man would drive who’s withdrawing from the world to nurse a broken heart.

He wouldn’t be Guy Madison without his great love for the outdoors. Whenever he can squeeze it into his busy schedule, he takes off on hunting trips. This fall he plans to go antelope hunting in Wyoming and this winter, if time permits, on a safari in Africa. Needless to say, he hunts only with the bow and arrow. It’s an interest he shares not only with Howard Hill but also with his other close friend, Rory Calhoun. These two and their wives, along with the Andy Devines, are the handful of people with whom he feels completely at home and relaxed and whom he visits frequently. In fact, he has most of his meals with them. Success hasn’t interfered with the loyalty he feels toward the few people he’s known for a long time, and it’s a good guess that it never will.

Guy was once quoted as saying that he wanted a round dozen kids. He didn’t have even one with Gail, and under the circumstances that was undoubtedly for the best. But Guy has a quiet way of going after and getting the things he wants. There’s no hiding the fact that he’s coming out of his shell—a new house, a new car, a new tux, and maybe a new girl. He’s found new pleasures, new assurance, and renewed joy of living. Luck, it would seem, has changed and is giving him a great big grin.

THE END

—BY ERNST JACOBI

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE DECEMBER 1954

No Comments