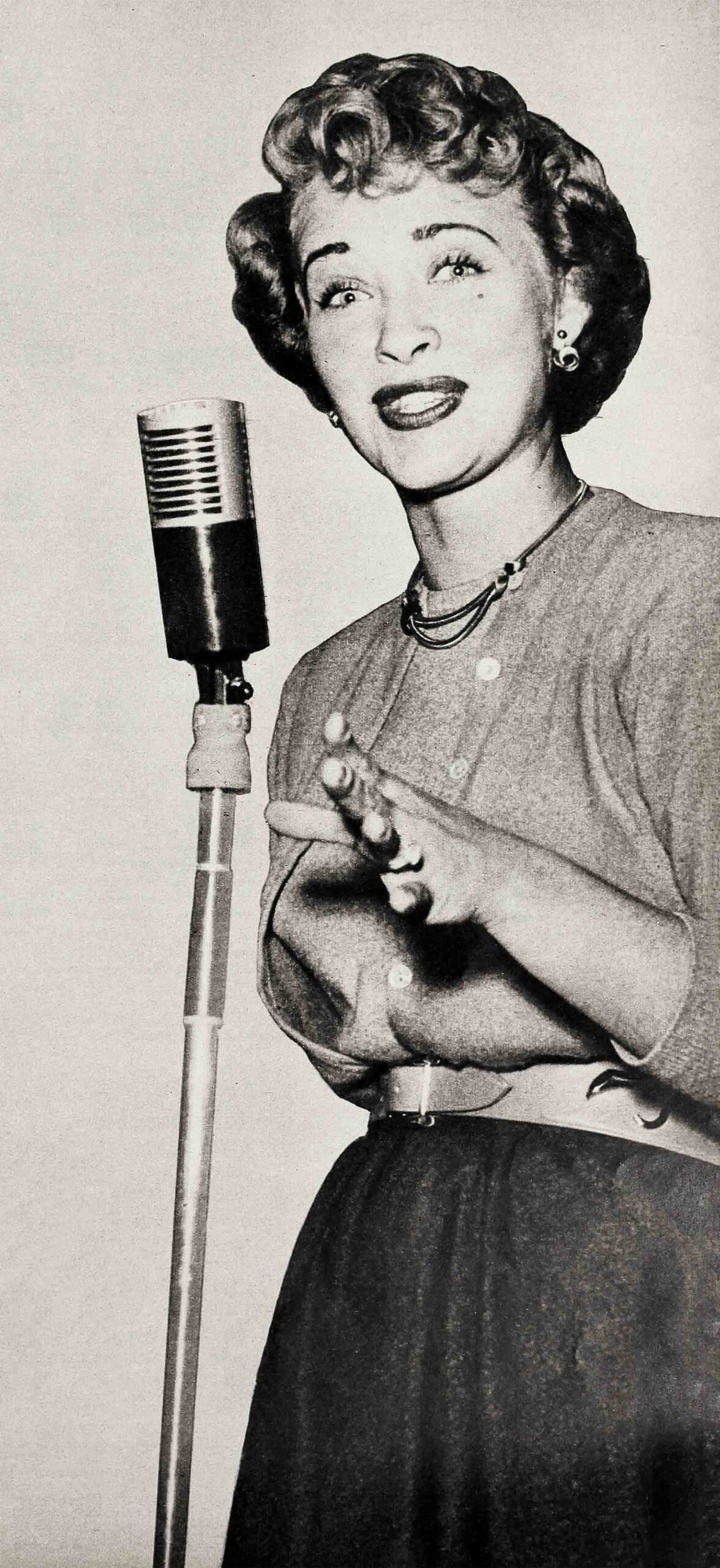

My Home Town—Jane Powell

Just about this time of year, Portland, Oregon, my home town, will be abloom with color and excitement and flowers. Visitors will come from all over America to see the famous annual Rose Festival. How I wish I could be there! I would like to stand on the sidelines with my husband Geary and watch the parade. Then I might recapture the wonderful thrill I had nine years ago when I was riding down the street myself on one of the biggest and prettiest of the floats.

Every now and then, I am overcome with nostalgia for my home town. I don’t think I’ll ever lose the special feeling I have for the place where I was born and where I lived the first 14 years of my life.

This spring, when I received an invitation to the pageant from the Portland Rose Festival committee, I showed the letter to Geary, who stared moodily into space after he read it.

“What’s the matter?” I asked.

“I just realized that I don’t know much about your life as a girl in Portland,” he laughed. “Maybe you had another fellow.”

“Of course, I did,” I replied. “Lots of them.”

That night, for the first time since we were married Geary and I had a long talk about my childhood. I don’t know why we haven’t discussed it before. I guess we’ve been too busy living our life together to do much reminiscing about the past.

It’s not easy for me to explain how I feel about Portland. It’s a big city, one of the biggest in the Pacific Northwest. Proud Oregonians will rush to tell you about its booming industry, its majestic scenic beauties, and its rapid population growth. But I don’t think of Portland that way. To me, it will always be the warm and neighborly place that ten years ago took a little girl named Suzanne Burce to its heart and helped her become what she is today.

I believe I owe more to my home town than any other performer in Hollywood. Some actresses got their first encouragement in their home towns. Others were given their first professional experience there. But no one I have met in Hollywood ever received the whole-hearted support I did from the people of Portland.

I might not be in Hollywood today if it weren’t for C. W. Myers, the late president of Portland’s local station, KOIN. Mr. Myers arranged for me to appear on “Hollywood Showcase” during the summer of 1943, when I was on a vacation in Southern California with my parents. At that time, I didn’t have the vaguest dream about a Hollywood career. In fact, my big ambition was to get back to Portland for the fall term at Grant High School. I never made it, I signed to make my first movie, instead. With Song Of The Open Road, the whole pattern of my life was changed.

Unfortunately; that is the point where most stories about me have begun. To be sure, appearing on “Hollywood Showcase” was one of the greatest moments of my life. But there were many things, important to me, that went before. Mother has told me that my first public appearance in Portland was at the annual recital of the Agnes Peters Dancing School, presented in the auditorium of Grant High School. I was only four-and-a-half at the time, and according to Mother, I wore a kitten costume she made and sang a number called, “Sitting On The Backyard Fence.” I remember the lyrics better than the occasion, I’m afraid, but it was at this recital that Carl Werner saw me. Later, as my agent and adviser, he played an important role in my career in Portland.

I don’t think I was precocious about dancing and singing. I remember little about my lessons. I took them with several other little girls, and was always glad to get away from studying to play.

My first year in school didn’t leave any deep impression on me, either. I know that I went to Irvington School, and that it was a long walk to get there. Mother used to worry about me because I always stopped to play hide ’n’ seek in some houses that were being built in the neighborhood. I quit this game after a board fell on my foot.

The next year, I transfered to Fernwood, a school 12 blocks from the Broadway apartment house my folks managed. I remember my second grade class very well because there I met my first boyfriend, Larry Larsen. It wasn’t exactly a romance, but we had a mutual bond. I bit my nails and Larry sucked his thumb. Our teacher, Miss Shaw, used to pay us a dime for each week that we controlled our nervous habits in class. All the time that I went to Fernwood, which was through the sixth grade, I came home every day for lunch, and I had to run both ways in order to get back before the bell.

My best friend at Fernwood was Larry’s sister Norma with whom I played every afternoon after school. I didn’t have a room of my own, but slept on a couch in the living room under a window, and I used to hand my doll things out to Norma through the window. Mother didn’t approve of this, but it saved a lot of time.

My grade school days were perfectly normal. I was an average student, thought more about playing than anything A else. Mother let me quit my dancing lessons when I lost interest in the third grade. I didn’t begin singing lessons un I was almost 11 years old, and I nearly stopped them because I dreaded practicing so much.

I took my first singing lessons from Mrs. Olson, who had an office in an old brick building across from the Lipman and Wolfe Department Store. Mother let me ride the bus back and forth by myself, and these twice weekly trips, my first solo expeditions into downtown Portland, made me feel important. More clearly than the lessons themselves, I remember the creaky old elevator in the building which stopped erratically whenever it took a notion. I was so afraid that I’d get stuck between floors that I usually walked up the four flights to Mrs. Olson’s office.

While I was in the sixth grade, we moved to another neighborhood but I still went to Fernwood, even though it meant walking even farther to school. Norma Larsen was still my best friend, too, and she often went downtown with me on the bus.

I remember the first shopping expedition we made together, one Saturday when our mothers allowed each of us to buy a dress by ourselves at Sears Roebuck. The dresses we selected were pretty enough, but my mother was furious because our dresses were exactly alike. After my first six months of vocal study, my singing teacher told mother that she thought my voice had promise and that I should be forced to practice. Mother didn’t believe in that method. But one Saturday morning a few weeks later, she and I went to an audition at the Hollywood Theater, which was running an amateur contest sponsored by 7-Up. When I sang for Del Milne, the theater manager, he encouraged me to enter, and no one was more surprised than I when, the following week, I won the contest, and later, the grand elimination prize.

During the weeks that followed, Mr. Milne arranged for me to sing at a number of benefit shows in Portland, including a Lions’ Club benefit for the blind to which Mr. Milne invited a number of the local radio station executives. Among that group was Mr. Joseph Sampietro, musical director of KOIN, with whose orchestra I sang many times during the next two years. A few days later, I was asked to audition by one of the other stations, but, when I sang, they told me I should go home and practice some more.

Then, one day in March, 1941, Mother took a girl friend and me downtown to see a matinee. We were preoccupied with window-shopping when I noticed Mother talking to a man on the street. It turned out to be Carl Werner, who had handled the publicity for the Agnes Peters recital. Apparently, Mr. Werner had asked Mother what I had been doing with my dancing, for she called me over to meet him. When he learned that I was singing, he suggested that I audition at KOIN for the Oregon War Bond Committee which was about to select an Oregon Victory Girl. I was thrilled when they chose me after I sang for them. But Mother insisted that I finish grammar school first.

“Mother, please let me try it,” I pleaded.

“You can’t just try it,” Mother told me. “You’ll have to give it your very best, and you can’t do that until you finish your semester in grammar school.”

“Oh, all right,” I agreed, reluctantly.

I could hardly wait until school finished that summer. But some of my impatience was abated by the thrill of getting my uniforms fitted, by the new songs I was learning, and by the tremendous opportunities which I knew lay ahead of me.

That summer I was almost literally adopted by the men who made up the Oregon War Bond Committee, whom I came to call my “uncles” as the bond drive progressed. They included Carl Werner, C. W. Myers, Mayor Earl Riley, Harvey Wells (Dean of the Oregon State Legislature), Larry Hilaire, Al Fink, William Mears, and other prominent Portland business men. They did everything possible to launch my career. Before school started in September, I was singing every week on KOIN’s “Victory Harvest” program.

In the midst of all this activity, I started back for my last year at Beaumont School. By November, I began to realize what Mother meant when she said that I could not merely “try” if I accepted the job as Oregon’s Victory Girl. It was too big for that. Very soon, I found myself taking on a second weekly radio show on KOIN, “The Million Dollar Club,” which honored the people who had sold more than $1,000,000 worth of war bonds. That November, I christened a Liberty ship at the Kaiser shipyards, sang at the USO regularly, made appearances at the shipyards and war plants around Portland. During that fall term at Beaumont, I missed 30 out of 90 days in class.

I don’t believe any 13 year old has ever been as busy, or loved every minute of it more than I did.

During the following spring, the war bond program gained momentum, and I gained momentum with it, traveling with the “Victory Harvest” program to a different Oregon city each week. In all, we covered 34 out of Oregon’s 36 counties. My traveling companion on the trips away from Portland was Carol Worth, Miss Oregon of 1943, whom I understand is now married and living in Long Beach, California. Sometimes, we entertained at war plants, playing a show for each of the shifts. The effort certainly paid off. Oregon was among the top five states in war bond sales.

It isn’t easy for me to single out the greatest thrills of my life as Oregon’s Victory Girl. There were so many. But I’ll never forget singing before the Joint Session of the Oregon State Legislature on Washington’s Birthday. Or the day, shortly before I was 14, that I was made a member of the “Million Dollar Club.” Or the time Carl Greve, a Portland jeweler who sponsored my first commercial radio program, presented me with a diamond ring—my first real diamond ring.

These are but a few of the experiences which tie my heart to Portland. I can still remember the special kidding I used to take from Chet Duncan of KOIN as he dropped the microphone down to my singing level. And my mother’s regular warning to stay dry and warm if I was to sing out of doors. And the many afternoons that Nancy Dickson and I spent roller skating on the tennis courts of the Beaumont School grounds, or the nights that we mystified each other telling our fortunes on her ouija board. I hope Nancy has found as much happiness as I have.

When I was signed for movies after my appearance on “Hollywood Showcase,” I started the ninth grade on the Universal lot, and finished the rest of my high school work in studio schools.

Of course, the biggest thrill of my whole life was the world premiere of my first picture, Song Of The Open Road, which was held in Portland during the Rose Festival of 1944. What a home-coming! On the day I arrived, rain was pouring down, yet thousands of people lined the streets to wave hello at me. Later, there was a big reception at the public auditorium and, that night, the premiere. I was 15, and absolutely speechless with happiness, especially when, the next day, Mayor Riley named the summer concert center, where I had sung the year before, as the Jane Powell Concert Center.

Unfortunately, I haven’t been able to make another prolonged visit to Portland. I went back for a benefit concert for the Symphony Orchestra a few years ago. But because of my schedule in Hollywood, I didn’t get a chance to stay long. It’s like so many things which are a fond but not an immediate part of our lives . . . we keep putting them off, while our anticipation grows and grows.

Now that our baby is getting old enough to travel, Geary and I hope that. it won’t be long before we can take a relaxed trip back to my home town. He was ready to go as soon as I told him about the wonderful skiing on Mt. Hood, whose majestic peak looms like a fairy castle against the eastern skyline of Portland. Because of my motion picture schedule, it won’t be this summer. But it will be soon. I miss my old home town.

THE END

—BY JANE POWELL

(Jane Powell can be seen in MGM’s Small Town Girl—Ed.)

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE JULY 1952

No Comments