A Little Boy Lost—Pier Angeli

In the living room of a small apartment, high above the bustle and noise of London’s Baker Street, three-year-old Perry Damone sat twiddling knobs on the dashboard of his new, large model car.

“Zoom . . . were off!” he announced, placing his feet on the pedals and moving off slowly around the room. “We’re off to see Daddy in America.”

“No, darling,” said his mother, Pier Angeli, who had just come into the room carrying a glass of milk. “Please don’t say that any more . . . just try to be patient and maybe, maybe one day soon he will be here with you.”

“But I want to see him now,” insisted Perry, his large deep brown eyes opening wide. “Why isn’t he here with us like he always was?”

“He will be . . . he will be,” said Pier softly, placing the milk on a low coffee table and going over to the window to look out on a cloudy, grey afternoon. She shivered slightly, thinking how much more like late autumn it seemed than like a June afternoon. Turning around again, she glanced over at Perry and sighed. It was so hard to explain to him that she’d separated from his father and that they’d even had preliminary divorce proceedings and that from now on he would only be seeing his father on certain particular days and occasions. Because Perry depended on his father so, and at every opportunity would speak about him and about the things they had done together.

As she looked at him, it occurred to her again how long his hair had grown. He hadn’t let anyone cut it since Vic had left home almost eight months ago, and now it almost reached to his shoulders.

“Perry,” she began, kneeling down near where he sat in his car. “Why don’t you let Mommy cut your hair? It may be a long time until Daddy can do it again. He’s very busy now—working hard.”

“No! Daddy do it!” answered Perry, with anger in his little voice. “Daddy always do it!” And this certainly was true. For, ever since Perry had been old enough to have his hair cut, his father had taken him regularly into the pale blue bathroom of their Los Angeles home, sat him on a high table, and made him laugh as he snipped at the wavy dark locks until they were short again. Now Vic wasn’t about to do it any more.

“Please darling—just for me,” insisted Pier. “You can’t go around with long hair like that. Everyone will look at you.

“No, please, no,” pleaded Perry, putting one hand up to his head as though to save his hair.

Pier sighed and sat down in an armchair. What was there to do? She’d tried everything. She’d never forget that awful day when she’d even attempted to take him to a special children’s barber . . .

It had been a beautiful, warm sunny day in March, that day in Los Angeles when they’d gone to the barber. As soon as they neared town, Perry had begun to jump up and down on the car seat, excited that he was being taken out “like a big boy.” She hadn’t told him yet that they might be stopping in somewhere for him to have his hair cut. Because earlier that morning, over the telephone, the barber had insisted it would be better if Perry knew nothing about it until he got there.

“Perry get new toy?” the child asked, as they slowed and turned into a parking lot.

She laughed. “Yes, darling,” she said. And, bringing the car to a halt, she got out and walked around to let him out as well, thinking how smart he looked in his new navy-and-white suit. If only that heir . . .

Holding onto her hand, he hopped and skipped by her side as they walked along the street, pulling back at every opportunity to peer into shop windows. Then, suddenly, he stopped quite still. “Look!” he said, pointing to a little grey elephant that sat in the front of one window. “Oh

. . . Mommy!” he gasped, turning to look up at her. “For Perry?”

They bought the elephant and then, quietly, trying not to let him see she was worried, she said, “Perry, I want you to be a very good boy when we go into the next shop. There are going to be a lot of other children in there, and I want to be proud of you. I want you to be the best boy of them all.”

“Yes, Mommy,” he said, but he really didn’t understand.

They turned the corner and then went through a doorway, past a sign which read “Children’s Beauty Parlor,” and into a large room crowded with boys and girls of all ages.

“Look over there, Perry, at those horses!” she said, pointing to a long line of picturesque high-chairs, carved and painted like wooden horses on a carousel. In each sat a small child, with a white towel about his neck, and behind each chair stood a white-coated barber with a pair of scissors.

On Perry’s face was a look of bewilderment.

As they stood in the doorway, a tall, grey-haired man came over’ towards them. “Mrs. Damone?” he said. And she nodded. Then he pointed to one of the high chairs at the far end of the room, which had just been left empty, and beckoned for her to bring Perry over there. But, as she picked him up, she felt uneasy. He was unusually quiet.

He didn’t make a move when the man wrapped a towel around his shoulders, but, when the barber came back holding a pair of scissors in his hand, Perry suddenly screwed up his face and started to scream. With his fists clenched, he lunged out with both arms, trying to push the man away.

“Stop it! Stop it!” he cried. “Daddy do it!”

“Please, Perry,” said Pier, putting a hand gently on his shoulder, “he won’t hurt you.”

“No!” screamed Perry. “No!”

Pier looked around. The noise Perry had been making had attracted the other children’s attention and now they were all staring at him.

“I don’t know what to do, Mrs. Damone,” the barber was saying. “Usually, once we get them in these chairs, they think it’s so much fun that they forget all about us and the haircut.”

She didn’t know what to say.

“Mommy . . . Mommy, don’t let him,” Perry cried, clutching her arm. “I wait for Daddy.”

“Okay . . . okay,” she said softly. Then she turned to the barber, and said, “I think we’d better leave . . .”

Picking Perry up from the chair, she kissed his cheek, trying to calm him. But he was still whimpering when they drove off.

“It’s all right, darling,” she said, leaning across the seat and putting one arm around him. “No one is going to touch we We’ll wait until Daddy can cut your hair.

But it wasn’t till much later in the day that Perry seemed to forget.

“Mommy! Mommy!” The sound of Perry’s voice brought Pier sharply out of her thoughts. She looked up and saw that he’d gotten out of his toy car and was standing over in the corner by the door to his bedroom. He wanted her to open it.

She got up and opened the door, smiling as she saw him scamper in and climb onto the bed. Reaching up to a shelf on the wall, he took hold of two picture books and brought them down. They were both stories about his favorite characters—Ba Ba the Elephant and Zephire the Monkey. He held them out to her. “Read to me . . . read to me, Mommy?” he asked, looking hopefully up at her.

“Yes, all right.” She sat down on the bed, and he curled up next to her, eager for her to begin. But, as she opened the book, a tiny pair of bathing trunks, tossed in a corner of Perry’s room, caught her eye. They made her remember something she’d been trying not to think of made her remember the day in Las Palmas, in the Canary Islands, not so many weeks ago (she’d been on location for “SOS Pacific”) when Perry had shown her just how much he missed his father.

That day Pier hadn’t been filming and so she’d told the nurse, Abbie, to take the whole day off—she would look after Perry.

“What about the two of us going to the beach for the day?” she suggested to Perry as soon as the nurse had left.

“Mmm,” he answered, his eyes lighting up. And he began kicking the legs of his chair with excitement.

Humming softly to herself, Pier went through into the bathroom. She slipped quickly into a bathing suit, pulling a loose cotton wrapover over it. Then she took Perry by the hand and they walked along the corridor to the room he shared with his nurse. There, she found his bathing trunks and put them on him, collecting his large rubber toy duck before they left the room.

Once down on the beach, she looked around for a secluded corner, where Perry could build sandcastles and be quite safe, and then stretched out next to him on a towel. But it wasn’t many minutes before he began pulling at her. “Can I go in the water?” he asked, sounding so coy that she had to smile.

“Yes, of course, darling. I can’t come in with you, though, because I can’t swim. But I’ll take you down to the water and you can splash about on the edge.” She got up, took him by the hand and they went running down across the sands towards the sea. When they reached a shallow bank where gentle waves lapped over and over and then ran back again to the deeper ocean, Perry waded in happily.

But he had only played in the water a few moments before he said, “No fun without Daddy. I want Daddy.”

“He’s away in America—working and singing for Perry,” she answered, as she always did when he asked. Someday, she thought, he would have to know the truth but now he was definitely still too young to understand. There was such a lost look on Perry’s face that Pier herself felt lost. . . . His father had always taken him swimming.

Then, before she knew what he was doing, he threw back his little head and started running down the beach. “Perry!” she called. “Perry . . . come back!”

He didn’t answer. He just shouted, “Daddy . . . Daddy!”

She hurried after him and then her footsteps slowed. She had seen what had made him run off. For he had stopped by a man who, from the back, looked exactly like Vic. “Daddy . . . my Daddy is here,” she heard him say as he threw his arms around the man’s legs.

But when the man turned around, and Perry saw that it wasn’t his father, he flushed a deep red and put a finger up to his mouth. Then he began to cry softly, brokenly.

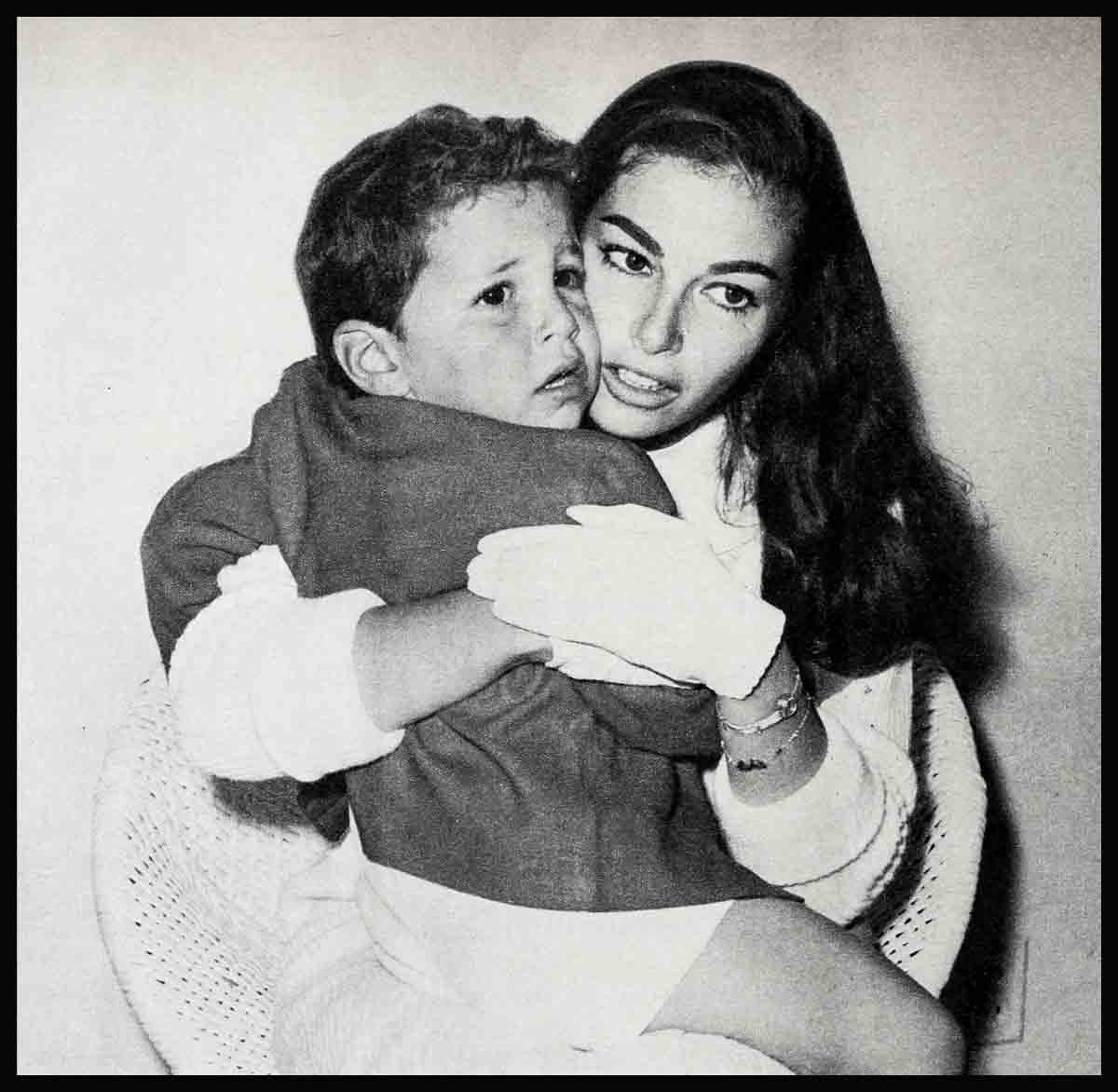

Pier reached him at that moment, and she bent down to pick Perry up. Holding him very close to her, she said, “No, darling . . . it’s not Daddy.” Then, turning to the man, she explained, “My son thought you were his father. I hope you will excuse us.”

“That’s quite all right,” he answered. “Is there anything I can do? Your boy seems terribly upset.”

“No . . . no thank you,” said Pier. And she took Perry away, speaking softly to him, trying to comfort him. “Daddy’s only away because he’s singing for Perry. He’ll be back soon,” she said gently. But the look of complete hopelessness on Perry’s face made her want to cry.

She carried Perry all the way back to the hotel, put him quietly to bed, and then read to him from his favorite Ba Ba book until he had calmed down and fallen asleep. Sleep did not come to her so easily that night, and, when it did finally, it did not last long. Waking suddenly, she heard him crying in his crib. “Where’s my daddy? Where’s my daddy?” he was saying over and over again.

Running into his bedroom, she picked him up and tried to comfort him. But it was a long time before he fell asleep again. She knew she had to do something. She couldn’t go on letting Perry feel so lost. But what? What could she do?

“Mommy . . . Mommy, why don’t you start reading?” Perry interrupted her thoughts again.

“I’m sorry,” she said softly.

And he snuggled closer to her. “It’s all right, Mommy,” he said, “but please—don’t look so sad.” Then, in one of those amazing spurts of understanding children sometimes have, he added, “I miss Daddy too.”

Pier smiled weakly and, looking back down at the book, finished the story. But she couldn’t help thinking about how much Perry talked about his father. He seemed to talk of nothing else these days, and it worried her.

Finishing the story, she tucked him in, and kissed him good-night. Poor little fellow, she thought. For weeks now, he’d been refusing to eat—except to have “eggs over easy” like his father always had, and spinach—“because Daddy likes spinach.” She’d taken him to doctors in Los Angeles, doctors in London and doctors in Las Palmas, but they hadn’t been able to help. She’d talked with friends who had boys of Perry’s age, but they didn’t know what to tell her.

He seemed to be pining so much—always asking why his father never played to him any more on the guitar; never sang to him or read to him when he went to bed; never took him to “that big park” (the golf course) to sit him in a caddy’s basket and wheel him around the course while he played. And whenever Vic’s voice came to them over the radio, singing one of his latest songs, Perry would always run to her and shout, “It’s my daddy!” He knew his father’s voice so well.

Lately, he’d begun to draw pictures, and he’d tell her, “This is my daddy.” She’d been surprised at the way he’d drawn the faces with curly hair—just like his father’s—and shaped the eyes exactly in the unusual shape of his father’s eyes. . . .

She heard the doorbell ring and so she left Perry’s pale blue bedroom and walked back through the living room to answer it, wondering as she went who it might be . . . she couldn’t remember having invited anyone to come over that afternoon . . .

When she opened the door she gasped and her hands flew to her face. For there stood Vic—laden with boxes and packages so big she could only just see his face.

“Vic . . . I . . . I didn’t know . . . why . . .” she stuttered in surprise.

“May I . . . may I come in?” he said in a small voice.

Pier stood back to let him pass, not knowing quite what to say. And then, as he walked into the living room, Perry saw him from the bed, and the boy came running over towards him shouting, “Daddy . . . Daddy. It is my daddy!” And he clung to Vic’s legs, struggling to be picked up.

Then Perry noticed that Pier was crying. “Mommy . . . why are you crying?” he asked, not understanding how such a marvelous thing as his father’s arrival after so long could make anyone want to cry.

“It’s nothing,” said Pier, embarrassed by her son’s question.

Vic sank into a chair and Pier knelt down beside him while Perry climbed onto his lap, wrapping his small arms tightly around Vic’s neck.

As the boy clung to his father, an un-spoken question seemed to pass between Vie and Pier.

“Are you home for always, Daddy?” Perry asked. But he didn’t stop for an answer. Instead, he climbed quickly down from the chair and disappeared into his mother’s bedroom.

A few moments later he came back with a pair of scissors. “Daddy cut my hair?” he asked.

Vic laughed and Pier laughed with him, but the laughter caught in her throat. “He hasn’t let anyone touch his hair since you left,” she explained, “and don’t think I haven’t tried. He keeps saying, ‘No, Daddy do it.’ ”

“I know, I know,” Vic said, as he began snipping away at his son’s dark hair, “a child needs his father.”

Pier looked at Vic, and then she looked away. “But—”

“I haven’t gambled in a year,” Vic said softly, “not even when I was singing in Las Vegas for a month. Not one dollar, Pier.”

Pier nodded, but she did not speak.

“And your mother I will try, darling. I promise I will. After all, she’s Perry’s grandmother. Pier?” He did not, perhaps he really could not, finish the question.

But Pier reached out and took his hand. “Yes, Vic,” she said, “let’s try. I think . . . it will work. It has to.” They both looked at Perry.

“He needs someone to play with,” Vic said, and Pier held Vic’s hand more tightly.

And then the boy had the answer to his question. “It looks like I’m back for always and always, Perry,” Vic told him.

Perry beamed, and, through her tears, so did Pier.

Then Vic began unpacking the parcels he had brought with him. There was a magnificent electric train—with fifteen different parts!—for Perry; for Pier, an exquisite ruby and diamond leaf brooch with earrings to match. And they began to talk about the future and about how they’d all go back to the States together (although Vic would have to fly just a few days earlier for singing engagements he’d already made) and when they arrived they’d stay in New York for a few weeks so that Vic’s parents could see Perry—they hadn’t seen him since he was six months old. They talked, too, of another child that they hoped they might have—soon.

That night, for the first time in eight months, Vic tucked his son into bed. “But, Daddy, I’ve still got to say my prayers,” Perry told him, as Vic was about to put off the lights.

So Vic watched as Perry climbed out of bed and knelt on the floor and said—as he always said—“God bless Mommy. God bless Daddy and make Perry good. God is great. God is good. And thank you God for . . .” he stopped and, turning his head around to look up at his father, added shyly, “for Daddy coming home! Make Daddy stay, and I will be good boy—always!”

THE END

PIER RECENTLY SIGNED WITH ROULETTE RECCORDS, AND VIC’S, OF COURSE, ARE COLUMBIA.

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE SEPTEMBER 1959