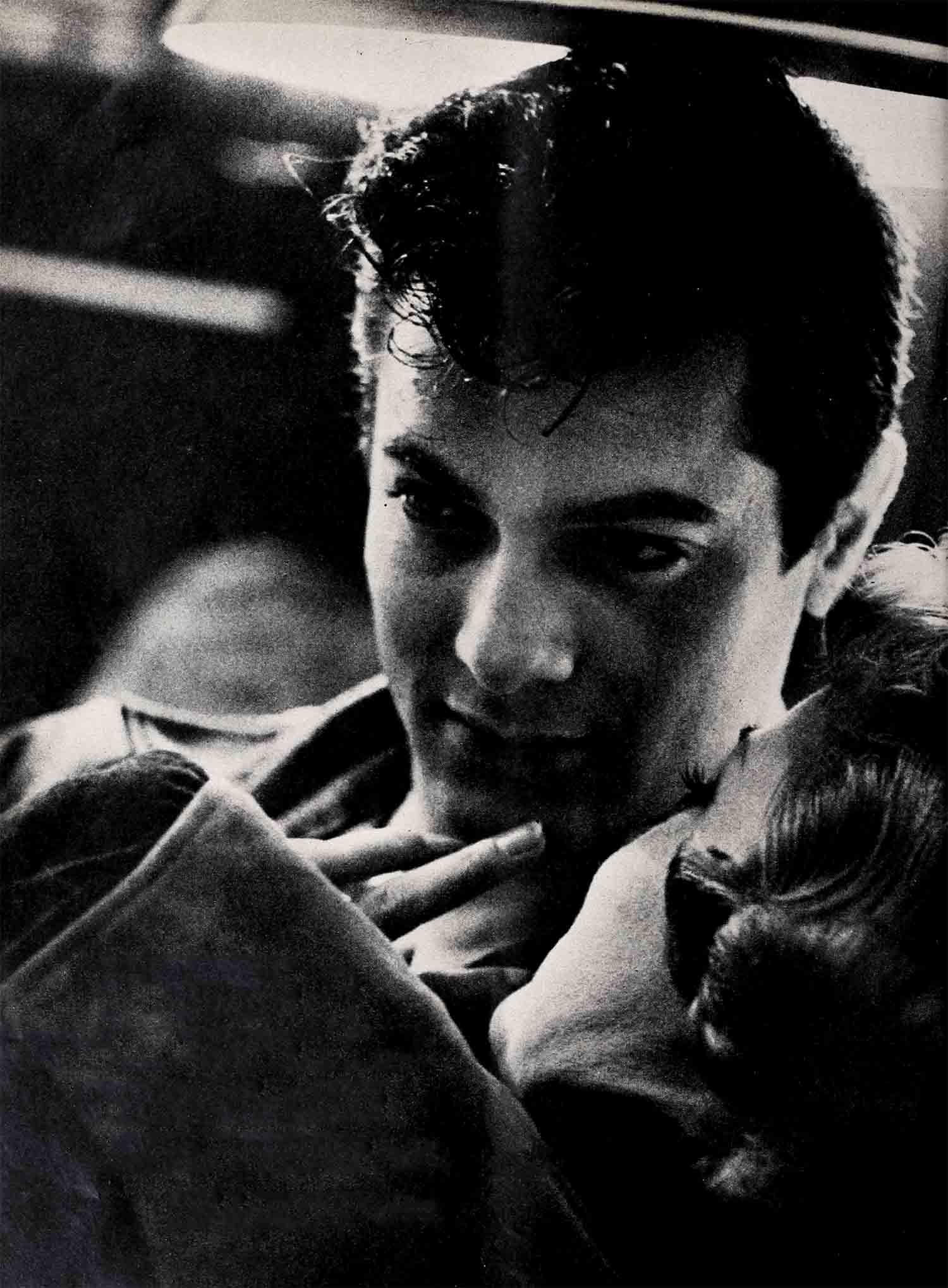

Tony Curtis’s Days Of Decision

He had a driving need to be noticed. The New York streets were his playground and constantly he felt the pressure of the big city. Near him, he saw opulent wealth while his own family lived in poverty.

To many a sensitive kid, this combination has been dangerous as a fuse attached to dynamite. Any sudden shock can explode it into juvenile delinquency and a life of crime.

For him, such a shock did occur. It was a shock so devastating that it threw his father into a serious illness and for a time broke up their home, their family.

Why, then, did Tony Curtis grow into a man who not only is a talented motion-picture star but who also is a responsible citizen whose public and private life is directed toward good?

Why didn’t he swing in the reverse direction and, propelled by this same driving energy, become an underworld character challenging all rivals for the title of Number One hoodlum?

Tony knows. He says crisply, “I met a settlement worker named Paul Schwartz.”

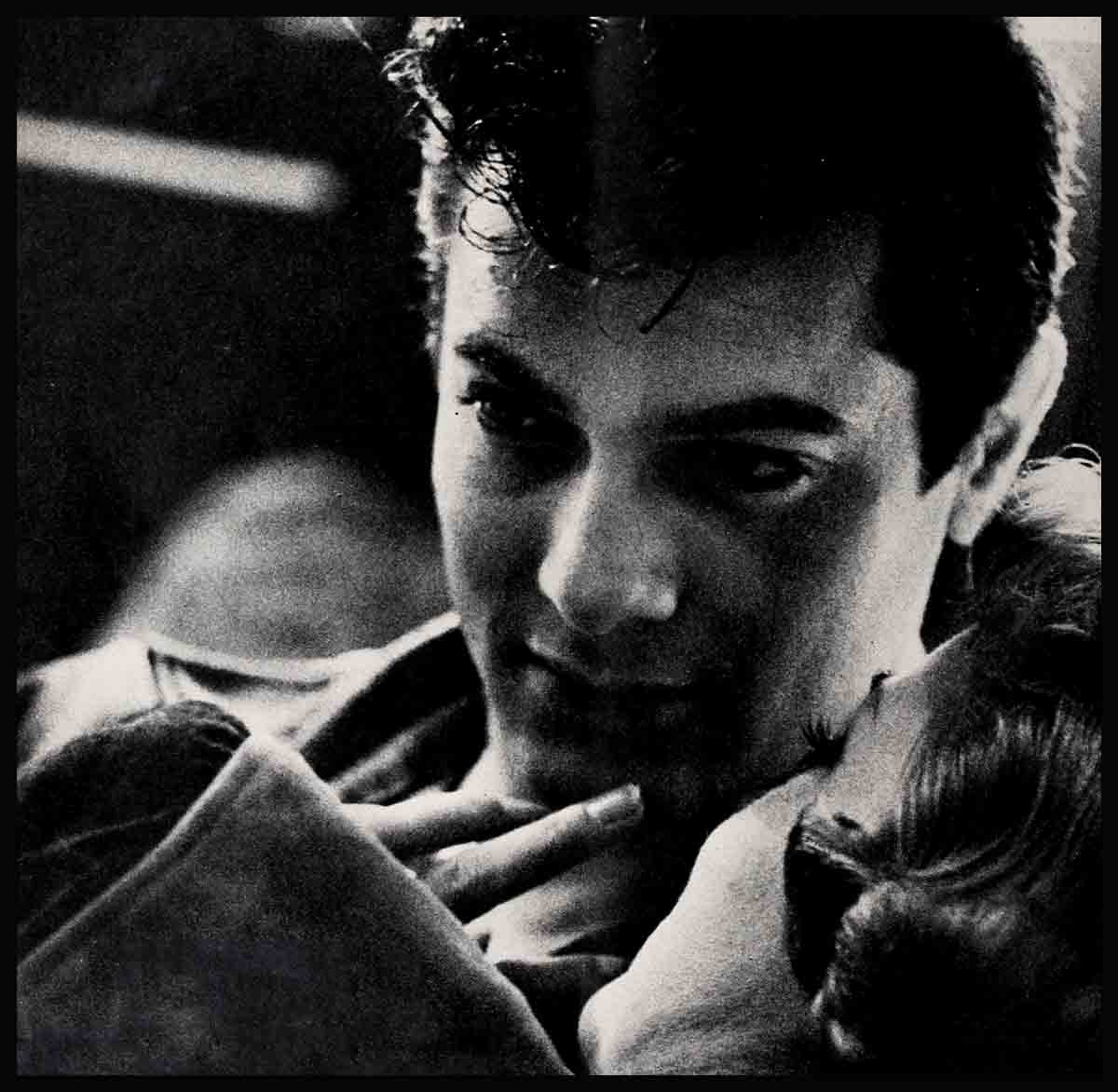

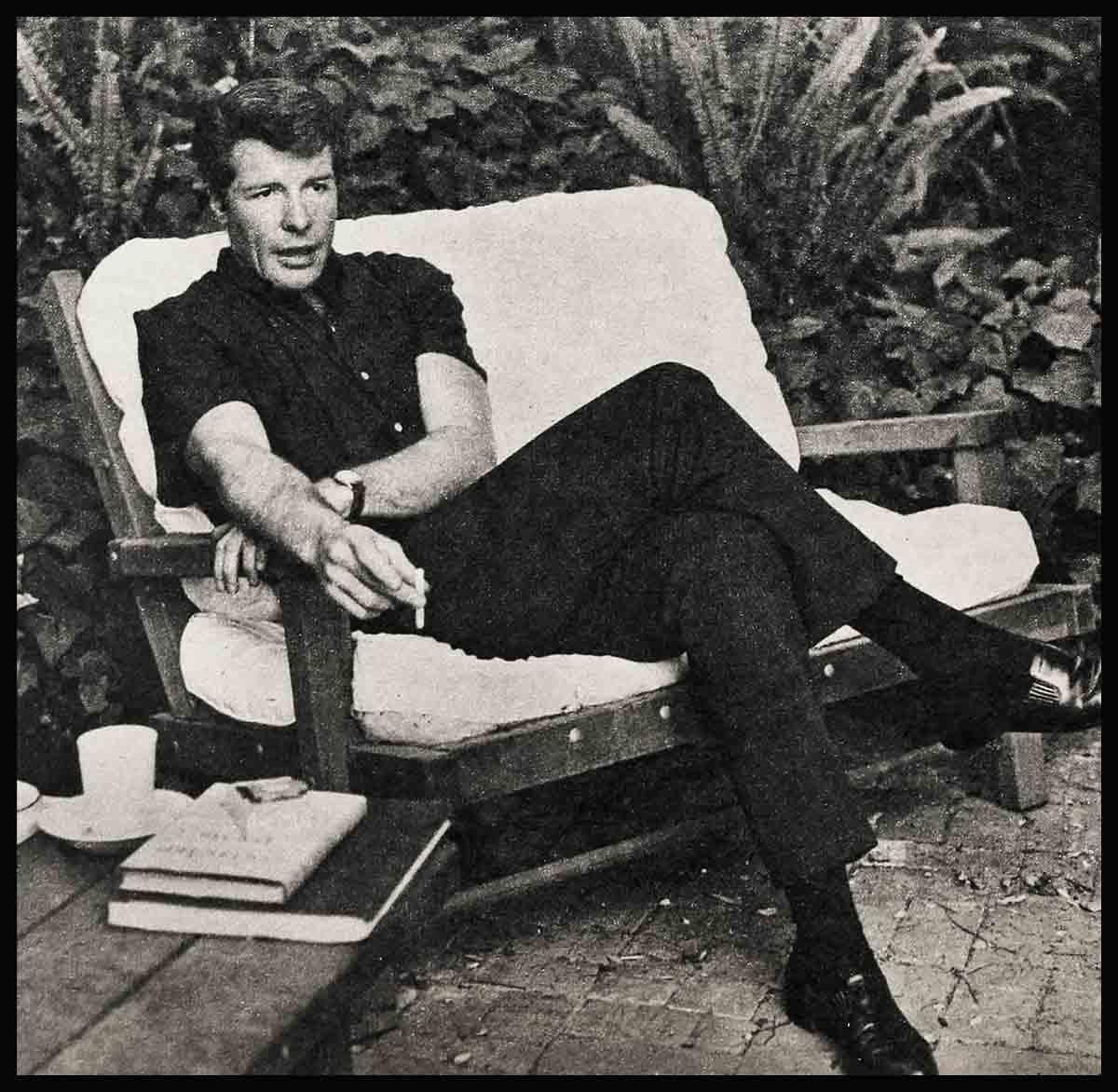

Tony’s wife, the lovely Janet Leigh, knows. Since theirs is a marriage where each has shared past as well as present, she knows the turning point in his life as certainly as if she had spent those trying childhood years beside him.

Eagerly, her face aglow with love, she says, “Tony could have gone either way. I respect him because even as a child he chose the right way. He had the courage to face a crisis.”

Tony’s boyhood friends, Sidney Schulman and Sam Negrin, know.

Sidney Schulman, who helps manage his own family’s prosperous supermarket, says, “His folks never failed him. They gave him love and freedom.”

Sam Negrin, who has chosen as his own career the work of social service among troubled juveniles, nods in agreement with all three, but casts his vote for Tony himself, saying, “You can’t discount the guy’s own effort. No family can give more than assurance. No social worker can do more than open a door. After that, it’s up to the kid himself to walk through it.”

But while his childhood was passing slowly into adulthood, things didn’t seem quite that simple to a sensitive kid. These three persons who hold Tony Curtis in respect and affection, unfold a story which rivals a film plot. Janet, particularly, feels its excitement. To her, Tony’s choice of which life to lead is more thrilling than any adventure which either of them has ever brought to the screen.

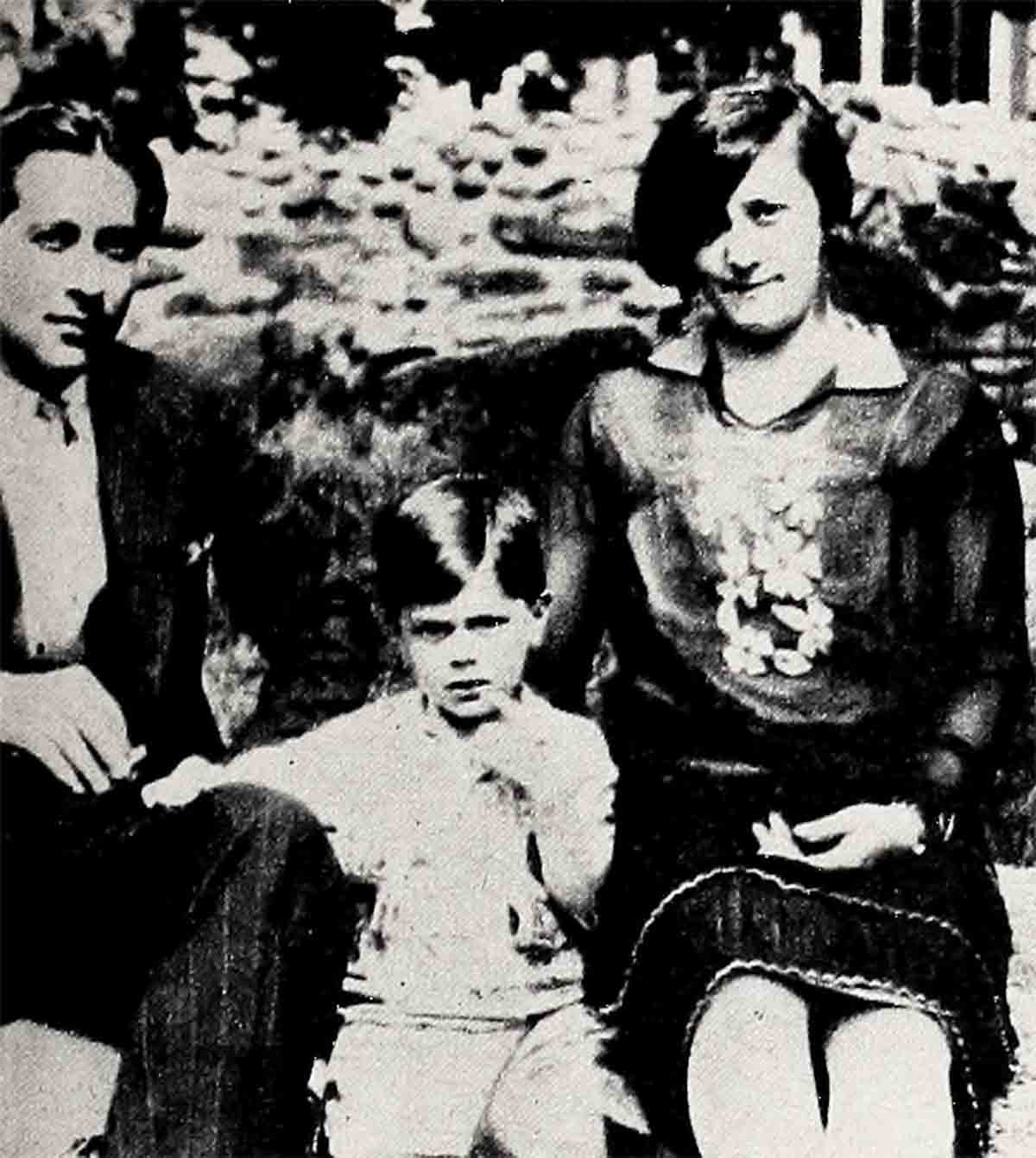

Tony was Bernie Schwartz in those days, a youngster with dark hair and bright blue eyes. Born in New York’s Flower Hospital on June 3, 1926, he was the first son of Mono and Helen Schwartz, Hungarian immigrants.

In Budapest, his father Mono had been a light-hearted, handsome young actor. In New York during the moneyless Thirties, his alien tongue barred him from the stage. To support his family, he worked as a tailor and operated his own cleaning and pressing business.

Times were hard for everyone, but for the Schwartzes they were bitter. They knew what it was to go hungry and to be dispossessed. Too often they saw their pitifully meager belongings dumped into the street when they could not pay their rent. Mono, laboring under the double handicap of learning a new trade during a period of financial distress, hadn’t a chance to provide the comforts he wanted to give his family.

When their second son, Julius, was born, things got even tougher. Proud Mono Schwartz had to swallow his pride and build Bernie a little shoeshine box. The nickels and dimes the child could earn on the street were needed to help Mono feed the family.

Only in love of each other was the Schwartz family rich. However bad things got, that never wavered.

The bright spots of those grim times were the Sundays when they could walk in Central Park. There, while Papa Schwartz told him of the colorful days of the theatre back in Budapest, little Bernie learned to dream and to try to act out his dreams. His parents were his indulgent audience—an audience which, in watching him, found brief escape from their own troubles.

Mono Schwartz, forgetful that his young son at the age of eight still spoke Hungarian, would watch the mimicry and see the boy replacing him on the stage. To Mama, he would repeat his favorite prophecy, “Our Bernie will be a fine actor.”

But at the same time, the city itself was teaching Bernie a different kind of acting. The shabbier he looked and the more eagerly he sought customers, the more he earned with his shoeshine box.

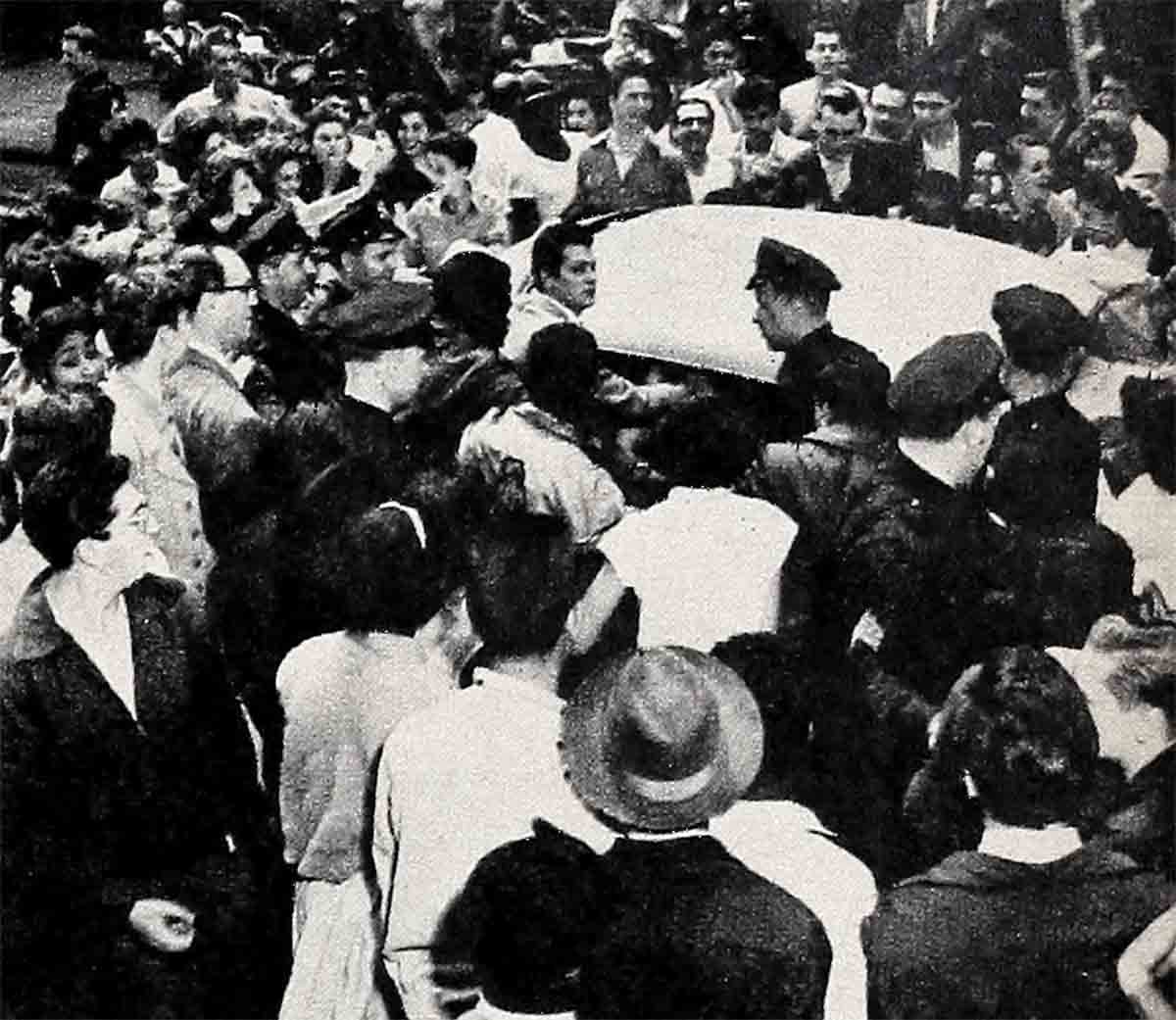

And then there was the neighborhood gang, kids from families as hard pressed as Bernie’s own. In the excitement of their games, they, too, could forget the empty cupboards at home.

Says Janet, “You know the way kids are. Tony wanted their approval, but he was just a kid on the edge of the gang. He didn’t really belong. So he’d try a little harder to excel. There’s always a challenge to make the game a little more exciting by making it a little more real.”

Bernie, by then age twelve, had one game where, because of his acting ability, he did excel. The dangerous game of “victim.”

It was an invention born of the East Side where truck drivers, intent on making the next light, roared along the arterial streets at a terrific pace.

Nimble Bernie and his pals made it produce both thrills and profit. Dodging in and out, they would pretend to be hit and fall moaning to the street. Bernie triumphed when he could make a driver pull up, thrust some money into his hand and rush away, calling over his shoulder, “I’m sorry, kid.”

The fact that he never once encountered a conscientious driver who would call the police or offer to take him to the hospital gave Bernie an extra measure of cynical daring. Playing “victim” was both more fun and more lucrative than shining shoes.

Then came the day when Bernie’s gang followed a parade. They were having a ball when friends ran up to tell them a child had been hit by a truck. One shouted to Bernie, “It looks like your brother.”

A minute later a traffic cop yelled at him, “Get over here and identify this kid.”

That was the shock. In that crisis, not only his brother’s life, but also Bernie’s future, balanced on a knife edge.

It is still in the front of Tony’s mind. He says, “That was the worst moment ever. Julie had always been more sensitive than I. I had planned how to help him over the rough spots so he wouldn’t have it so tough as I’d had. Now the worst had happened.”

Sharply, he recalls exactly how he felt. “I wanted to run for my folks. I wanted to scream for my mother. Then I knew I couldn’t do it. I had to act grown up. I think maybe I did grow up right then. I certainly was never really young again after I looked down and saw it was Julie.”

The streets, which nimble Bernie had regarded as his own playground, had this time claimed a real victim. In two days, Julie was dead.

Soon hate filed a sharp new edge to Bernie’s grief. In offering a two-thousand-dollar settlement, the lawyer for the trucking company said, “Too bad the boy didn’t live. That way you would have had a steady income for life. Not big, but continuing.”

Glaring at the man, Bernie promised himself that some day he would kill him.

Two months later, disaster again drove deep. Mono’s store was robbed and they lost everything.

It was too much for his father. Mono had a breakdown. Helen, Mono’s wife, overwhelmed by the tragic series of events, tried desperately to provide for her family. But her struggle went unrewarded and she was forced to put Bernie into a home. By the time his father recovered and reunited his family, young Bernie was carrying a heavy load of bitterness.

Says Janet, sharing that long-ago trial, “What does a boy do in a case like that? Whom should he blame? He could blame the trucking company. He could blame the city. He could blame society in general.”

There’s both sorrow and pride in her voice as she continues. “Right then, Tony found that wonderful quality which he has had to depend upon so many times. He faced up to the fact that his little brother had seen him play ‘victim.’ For Julie’s death, Tony blamed himself.”

But such self-blame also holds danger.

The feeling that he had brought death to his brother and sorrow to his beloved parents imposed a weight which not even their love for him could fully lift. Many a lad, bearing such a guilt, has concluded his own life is worthless and turned fanatically reckless.

Janet, recognizing how heavily the scales were tipping against Tony, says, “The gang was getting too old to act out a simple game of cops and robbers. That temptation to make it more real was creeping up on them. They hadn’t yet done anything seriously wrong, but they were close. Tony, wanting to find from the gang the companionship he had lost with the death of his brother, was ready to try anything to win from the gang the approval he could not give himself. I think he was close to doing something desperate. That’s why we bless Paul Schwartz.”

With the advent of Paul Schwartz (who was no relation) those tilted scales of fate got a man-sized heave in the other direction.

For Paul Schwartz, then program director at Henry Street Settlement House, was a dedicated man who had both excellent professional social-work training and also an inspired way of dealing with kids. Warm and friendly, he recognized the same thing Janet later identified—that many pranks are simply an attempt to act out an adventure. Paul Schwartz believed that a healthy session of dramatics on stage could eliminate a dangerous amount of malicious mischief on the streets. He let Bernie’s gang know they would be welcome at Henry Street.

Bernie was then about fifteen and alarmingly quiet. His grieving over Julie’s death, the separation from his parents while his father was ill had taken all the bounce out of him. He was frigidly withdrawn on the outside while seething with hurts, puzzlement, anger inside.

Says his friend Sam Negrin, “In the beginning, we had to needle him into coming out of his shell to try to do anything.”

Sam and Bernie met the day both turned up at Paul Schwartz’s office looking for the summer jobs which East Side kids regarded as fabulous.

Says Sam, “The official designation was ‘kitchen boy and counselor-in-training.’ In terms of work it actually meant that we went up to Henry Street’s camp at Mahopac Falls, New York, to wash dishes for one hundred and twenty-five people, scrub floors and ride herd on the smaller kids. The important thing to us was that we got a summer in the country, but we didn’t lose sight of the fact that we also were paid twenty dollars for those ten weeks’ work.”

Competition for the jobs was terrific and both boys felt as though they had just been knighted when they were among the lucky ones chosen. They were sent up to open the camp and get it ready for the other kids.

Sam’s recollection of that first night in the woods provides a capsule picture of fifteen-year-old Bernie Schwartz, his hopes, fears, anxieties.

This advance crew was small. To bed down for the night they set their cots in close formation in the dining hall, and as they prepared for bed even the toughest in the group was homesick.

Kids who had learned to sleep with neon signs glaring in their windows stared wide awake into the darkness; those who ignored the roar of the Third Avenue El jumped at the chirp of a cricket; boys who prowled vicious streets without thought were scared to set foot outside the door.

They were so jittery about the emptiness of the country that Bernie found no companions when he inquired timidly, “Don’t you want to go down to wash up?”

The washing-up shack was at least fifty yards down an unlighted path. One by one each of the kids answered, “Not me.” Bernie set out alone.

Sam grins ruefully as he recounts Act II of their little drama. “I should have had my ears pinned back,” he confesses, “but I set up a gag. We agreed that when Bernie returned, we’d give him a real scare.

The youngster was literally whistling in the dark as he approached the door. That was their signal to pile into bed and pretend sleep. Frightened and lonely, Bernie went from cot to cot whispering, “Hi, Joe. You asleep, Sam?” No one answered.

He bent to untie his shoes. That was the signal for all to jump up and yell “Boo!”

Says Sam, “I was no more than six inches from his ear and no one was further than a few feet away. We thought it hilarious when we yelled, but in a minute, we knew it wasn’t funny. Bernie fell back on his bed, his heart pounding so hard we could see it. For a half hour, he couldn’t get his breath. We thought he was going to die. That’s when I gave up practical jokes.”

But when it came to work, Bernie proved he was no weakling. He did more than his share of the scrubbing and never complained about blistered hands or sore muscles.

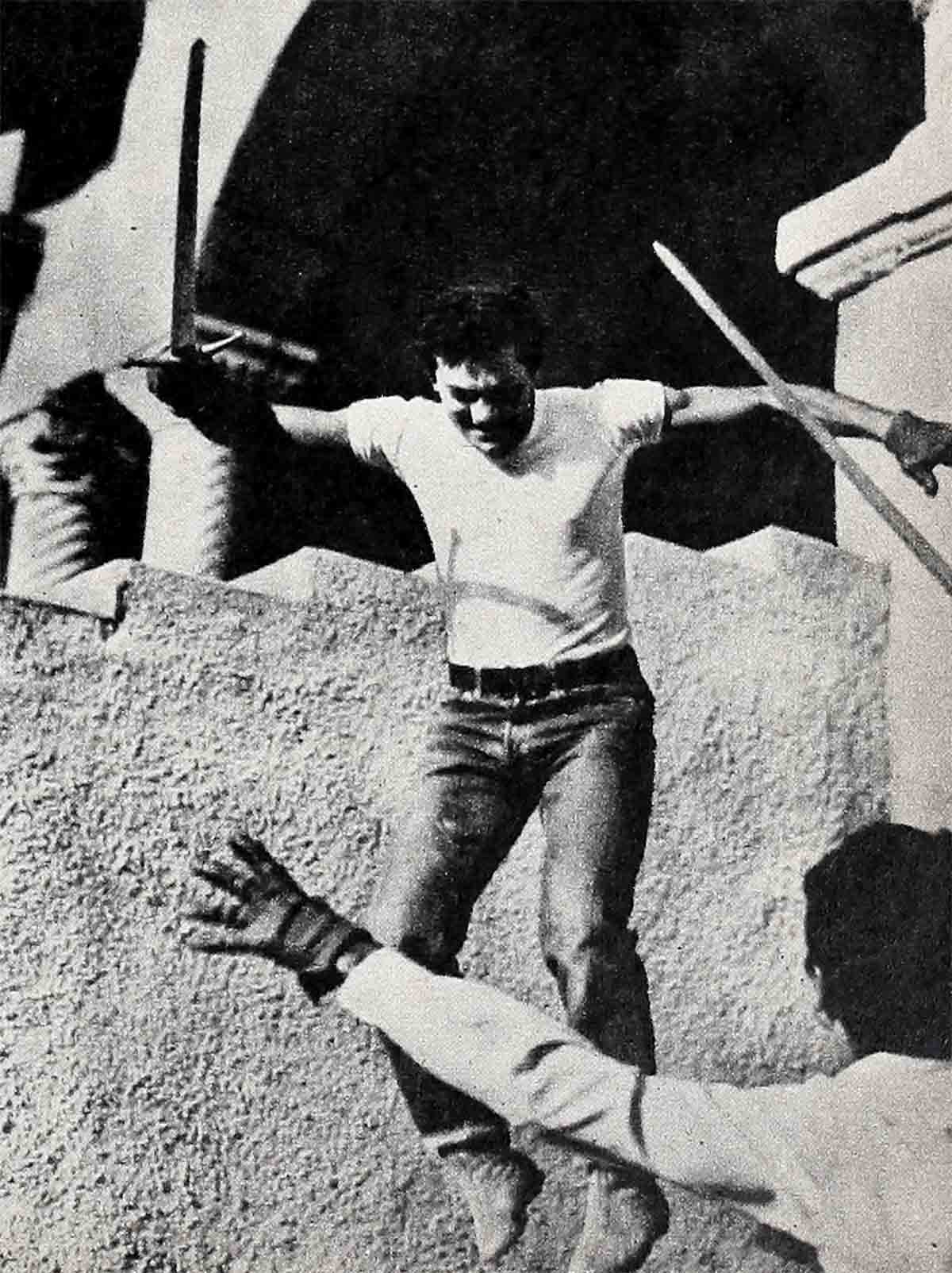

When the athletic program was started, Bernie came into his element. Says Sam, “He was our best tumbler, a sort of Douglas Fairbanks, j.g. He was so limber you wondered if he had a bone in his body. We spread our mattresses out on the grass ae could teach his tricks to the other kids.”

Bit by bit, Bernie Schwartz was coming out of his shell, but it was in the dramatic program that he really found himself.

Says Sam, “Paul Schwartz was hipped on dramatics. Putting on a musical show became the great project of the camp. We all pitched in to do everything. We wrote it, we rigged up costumes, we built sets.”

For Bernie, this was a realization of both his own dreams and his father’s. The theatre, which until then had seemed as distant and as impossibly unattainable as Mars, was suddenly alive and he was a part of it.

He was no star in that first camp production. In fact, the boy who was to become Tony Curtis, a big boxoffice attraction, never had a starring role at Henry Street Settlement.

But that never bothered him. Sam, with his present perspective, says, “He did find an opportunity to express himself. Besides that, he discovered in working on production that dreams could be turned into reality. He had the excitement of opening night and the satisfaction of doing a job well.”

Bernie Schwartz was a changed boy when he came back from camp that year. Sidney Schulman, who met him when both went to Seward Park High School, has a far different impression from that of the too-quiet, withdrawn, old-before-his-time kid whom Sam Negrin first saw.

Says Sidney, “Bernie was always acting, always clowning. We’d be riding the El home and he’d get his coat up over his head, pull his arms half out of his sleeves, waggle them and announce, ‘Look, I’m a rabbit.’ He’d do anything for a laugh.”

Bernie continued to go to Henry Street Settlement House. His second year at camp he was a full counselor. During the winter, there were always plays to work on under the inspired direction and example of Paul Schwartz.

Says Sam, “Bernie carried his own weight and worked well with the group. I was the real ham. I would have raised the devil if I hadn’t got lead roles, but not Bernie. He’d like as not be backstage pulling the curtain or going on in a half-dozen bit parts in each show.”

It was a proud night for Bernie Schwartz, son of Mono Schwartz, Budapest actor, when he first was able to invite his parents to see a show. Whatever his roles, he was able through them to breathe life into both his father’s dreams and his own. That was important to both of them, but an even more significant thing was happening so gradually that it was imperceptible at the time.

Bernie Schwartz was learning the give-and-take of living. He was able to accept guidance because he also had discovered that he, himself, had something to give back. He had started to find his place in the world. The danger of delinquency was past.

Sam Negrin, whose conversation blithely mixes jive talk with social-work terms, says, “He had begun to integrate—to accept his responsibilities as a young adult. He could make plans for his future. His parents had given him the assurance of being loved, and Paul Schwartz, who influenced us both so strongly, had opened the door, but it was Bernie alone who walked through that door and carried on from there. In fact, that cat was solid.”

Janet says, “It’s because of what Paul Schwartz and Henry Street did for Tony that we both believe so strongly in boys’ clubs and girls’ clubs.”

She’s too modest to add that their belief also turns into practical support. They have presented scholarships to Henry Street’s dramatic department, both to further the work that is being done for all the youngsters who need a healthy outlet for their pent-up emotions and to provide an opportunity for some really talented kid from the slums to have more advanced studies.

Even more important, both Tony and Janet give of their own free time whenever they’re needed. They manage to turn up at community houses in California to lend what is perhaps more valuable than money—the inspiration that comes’ from their example of the rewards of acting, both the financial rewards and the emotional rewards. Tony talks to the boys, giving tips on acting and on reading their lines. But most of all at these gatherings, Tony is remembering back a few years to the time when he too stood at the turning point of his life, a confused bundle of seething energy in a world that was too big for him to tackle and yet too small to help him try. And he’s wondering how many of these kids will find a solution as perfect as the one he has found. Not necessarily as an actor, although of course that would please him. And he’s hoping for the best, rooting for these kids the way his friends rooted for him not so long ago.

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE AUGUST 1954

No Comments