Morals And The Movies

A violent controversy over movie censorship is raging across the country, from Culver City to Jersey City, from the luncheon tables at the Brown Derby to the august halls of the Supreme Court. Judges disagree; producers disagree; officials disagree; critics disagree. Almost everybody has been heard from—except the persons whose interests are chiefly concerned. That’s you, of course.

It’s your morals that are being corrupted by Hollywood movies—or adequately protected or uplifted, according to the viewpoint. It’s your sensibilities that are being shocked—or treated with tender care. There has been much talk about public opinion on censorship, but so far nobody can say exactly what that opinion is. Photoplay has decided to take the simplest way of finding out—asking you. The ballot on this page is your chance to speak up. Fill it in and we will see that your opinions are forwarded to the men now debating Hollywood’s censorship problems.

Should movies be given more freedom from censorship? Are they so fenced in by outmoded bans that they can’t get anywhere near the realities of present-day life? Do movies need tighter restrictions? Have they gone on a binge of sizzling sex and raw brutality? Or is the present balance just right? Is there only a healthy amount of regulation? Decide for yourself and vote!

The Hollywood end of the row began when Samuel Goldwyn, highly respected producer, suggested that the Production Code should be brought up to date to get into step with changed standards in real life. This code is the self-censorship system that the movie industry set up for itself back in March 1930. Toward the end of the silent era, Hollywood became pretty free and easy with scenes of sex and violence. And when dialogue and sound arrived to give movies stronger impact, the storm broke. Church groups, women’s clubs, civic-minded organizations of all kinds rained protests on industry heads. State and city censor boards grew so scissors-happy that a picture might wind up with practically nothing left except two people fading into the sunset virtuously holding hands.

Leading producers had earlier formed an organization at a time when a few private-life scandals had brought the whole movie business under fire. Now the producers went into action to defend Hollywood in the new crisis. They made arrangements for the formulation of the Production Code, to set standards of decency in motion pictures. Certain “General Principles” were stated, beginning: “No picture shall be produced which will lower the moral standards of those who see it. Hence, the sympathy of the audience shall never be thrown to the side of crime. wrongdoing, evil or sin.”

Then the boundary lines were laid down specifically under eleven neat headings:

I. Crimes Against the Law; II. Sex; III. Vulgarity; IV. Obscenity; V. Profanity; VI. Costume; VII. Dances; VIII. Religion; IX. Locations; X. National Feelings; XI. Repellent Subjects.

This code, accepted by the major Hollywood studios twenty-four years ago, still controls your favorite entertainment today . . . Or does it? Before we see whether or not it will really work, let’s see how it works.

The Production Code is administered by nine men, all employees of the Association of Motion Picture Producers. These men are trained social scientists, ranging in age from thirty-five to sixty-five. As a group they represent almost every imaginable kind of social philosophy. They represent all religious backgrounds, a cross section of world geographical experience and a fascinating mélange of intellectuality and vulgarity, naiveté and sophistication, piety and iconoclasm.

A witty director once complained it was a waste of time to tell a risqué story in the Breen office (as the Hollywood home of the Production Code is called). “First of all, everybody’s heard it; in the second place, somebody knows a funnier version; finally, these guys can tell you how to clean it up so it can be used as a gag in a picture and how to muddy it up so that it will take the roof off at a smoker.”

These nine very human, beings check every script turned out by studios belonging to the organization to see whether it violates any section of the code. But their work doesn’t stop there. A script isn’t a finished movie. Lines or bits of action that look perfectly innocent in print can turn out on film looking anything but. Just think what a cameraman can do with a clever angle, an actor with a meaningful glance or an actress with a toss of the torso!

So the movie itself gets a second going- over. If it passes inspection (after some cuts or reshooting perhaps), it receives a Production Code seal and starts on its way to you. Or maybe it will reach your local theatre even without a seal. The restrictions of the code are voluntary; they can’t be enforced by law. A few producers have bowed out of the Association (usually just temporarily) and released a picture that had been refused a seal. “The Outlaw” is one instance, though this movie was withdrawn after its first showings, cut to conform with the code and released again with the blessing of the Breen office. But “The Moon Is Blue” went on its way happily without a seal, though censorship bodies in some localities clamped down on it.

These are outright rebellions against the Production Code. Other producers, agreeing with Goldwyn, have merely urged that the Association get together to revise the Code. After all, they point out, almost a quarter of a century has passed since it was formulated. Only a handful of changes have been made in it, and two of these tacked on extra taboos. Meantime, our country has struggled through a major economic depression and World War II. Standards have changed, it is maintained; even the Constitution has acquired new amendments. An entire generation has been born, has gone through school, has undergone combat experience, has worked, bled, loved, married, had children of its own and developed its own viewpoints. And, the revisionists say, the viewpoints of this group differ from those of the last generation.

Movie producers must be in tune with the times or they won’t be in the producing business very long. If you, and you, and a few million more of you stay away from a picture—no more such pictures will be made. So subtle ways have been devised to get around the Code, and some pictures have even smashed straight through it, apparently with the full approval of the Breen office.

Here is the startling fact: If the Production Code had been rigidly followed and enforced, at least ten of the top boxoffice and critical successes of 1953 and 1954 to date could not have been made at all!

1. THE MOON IS BLUE

This film was made from the stage play written by F. Hugh Herbert, himself a parent of beloved daughters, whose conversation suggested many of his hit themes and witty lines. “The Moon Is Blue” ran for two years on Broadway, then toured thirty-five American cities, including Boston, without one snip from local censors.

Yet, when Otto Preminger made this play into a movie—a near-duplicate of the original—the Breen office refused to give the picture a seal. Under the “Sex” section of the code comes Subhead 3, “Seduction or Rape,” stating (under Sub-item b): “They are never the proper subject for comedy.”

Let’s recall a sample of the controversial dialogue. Maggie McNamara and Bill Holden are riding in a taxi after he has picked her up (with considerable co-operation from her) atop the Empire State Building. She has just discovered that they’re bound for his apartment.

Maggie: Will you try to seduce me?

Bill (somewhat astonished): I don’t know . . . Probably . . . Why?

Maggie: Why? A girl wants to know . . . After all, there are lots of girls who don’t mind being seduced. Why pick on those who do?

Bill: Okay. I won’t make a single pass at you . . . I won’t take an oath that I’m not going to kiss you.

Maggie: Oh, that’s all right—kissing’s fun. I’ve no objection to that.

What was the general reaction to such dialogue? Well, “The Moon Is Blue” has been cleaning up at the boxoffice. A poll taken by a Photoplay reporter returned the verdict that out of twenty-two persons asked, twenty-one found nothing objectionable in the picture. Number 22 objected to the character played by David Niven. Church groups and local censors, however, have been much rougher on “The Moon Is Blue.”

2. THE FRENCH LINE

This picture, starring Jane Russell, opened in St. Louis to sellout performances. Refused a Production Code Seal, it was sent back to the cutting room for deletion of a dance done by Jane (who promptly applauded the Breen office verdict). This scene, said the nine men, violated Subhead 4 under “Costume”: “Dancing costumes intended to permit undue exposure or indecent movements in the dance are forbidden.”

A dance recently landed another luscious brunette on the cutting-room floor. Taking one look at Debra Paget’s undulations in “The Prince of the Nile,” 20th Century-Fox decided, “This will never get by.” Out the sequence went before the Breen office had a chance even to brandish a blue pencil.

3. ROMAN HOLIDAY

Endearing itself to critics and public alike, this charming fairy tale will undoubtedly be shown for years and years and wind up on television to delight generations still learning how to smile.

Yet “Roman Holiday” violates the second General Principle of the code: “Correct Standards of life, subject only to the requirements of drama and entertainment, shall be presented.”

“Roman Holiday” is, in essence, the story of a rebellious young girl who runs away from what serves as her home. She is inspired by anger and boredom with her job, not by any reason which might be considered desperate, such as mistreatment or threat to her virtue. She falls asleep on a bench in the public street, is rescued by a strange man, spends the night in his apartment, wearing his pajamas. The next morning, instead of rushing back to those who are worried to death over her absence, she continues her truancy, accepts money from her volunteer landlord, drives a motorbike without knowledge of its operation and winds up in police court, where leniency is granted because she is represented as the bride of Gregory Peck. (She isn’t.) Finally she is involved in a slugging match with duly constituted representatives of her government, conking one gentleman with a borrowed guitar, which is reduced to splinters. Furthermore, when this miscreant returns to her home, she sasses back those who try to point out that she has caused grave concern to her parents and jeopardized their jobs.

Does such behavior conform to “correct standards of life’? Do you think “Roman Holiday” should have been dropped in the deep hopper labeled “unsuitable for motion-picture production”?

4. FROM HERE TO ETERNITY

If you read the book on which the picture was based, you were undoubtedly astonished at the thoroughness of the clean-up job accomplished in the transition from print to film. The movie was a rousing popular success. It reaped a record crop of awards. Yet, if the Production Code had been interpreted literally, the story would never have reached the screen. It violates at least four sections of the Code.

After the heading “Sex” is the general statement: “The sancity of the institution of marriage and the home shall be upheld. Pictures shall not imply that low forms of sex relationship are the accepted or common thing.” Says Subhead I: “Adultery and Illicit Sex, sometimes necessary to plot material, must not be explicitly treated, or justified, or presented attractively.”

The sanctity of the institution of marriage is clearly labeled a sometime thing when the facts of Deborah Kerr’s marriage to the captain are explained. These facts are “explicitly” treated when the captain goes out on the town with his current girl and is seen by Deborah Kerr and Burt Lancaster, out on a small adventure of their own.

The scene on the beach between Deborah and Burt is not only “explicitly treated” and “justified,” but if it isn’t “presented attractively” then all beauty has gone out of the sight of waves crashing on a moonlit beach where two handsome beings in a passionate embrace are studied through romantic camera angles.

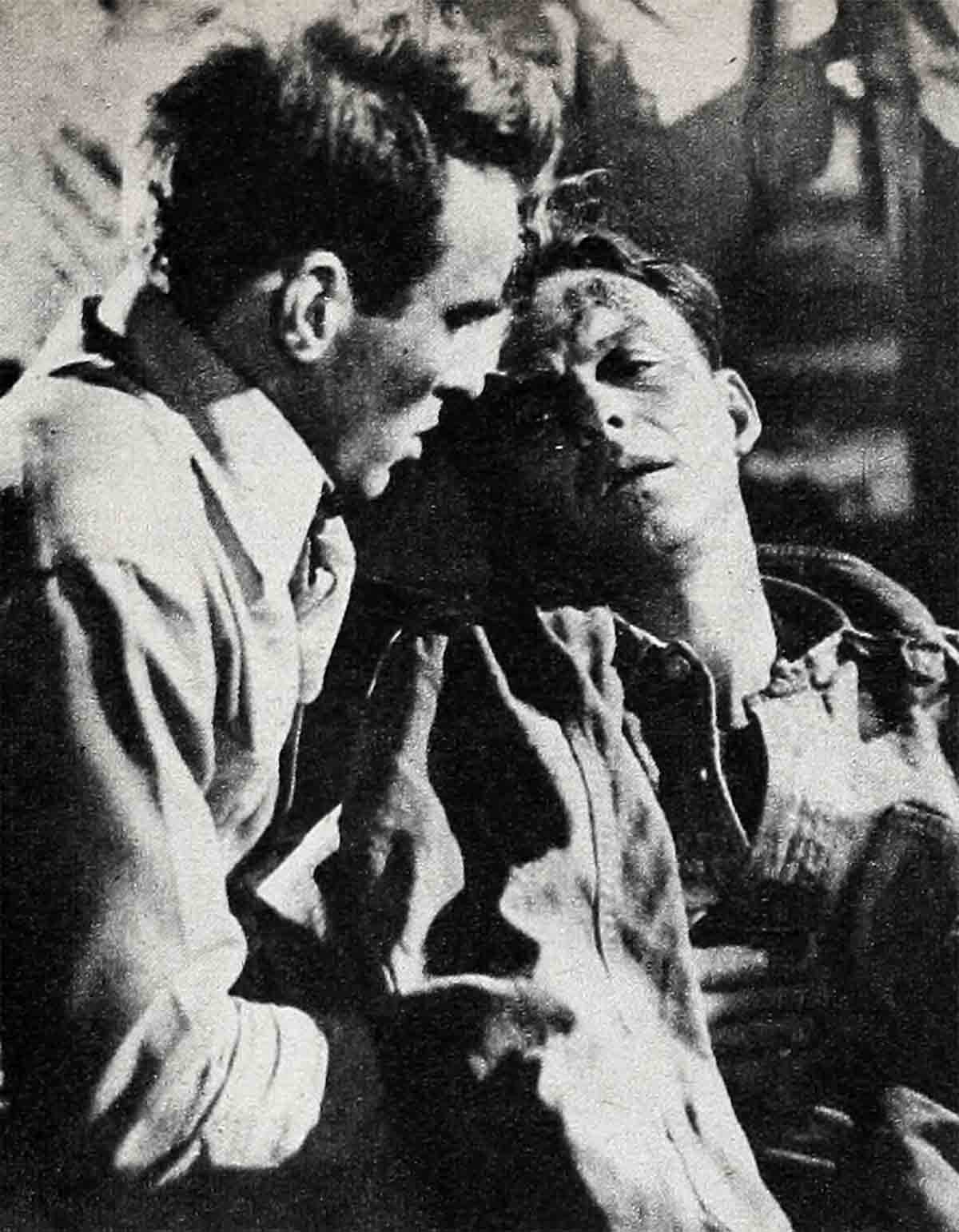

Also completely fractured is Subhead 3 under “Repellent Subjects”: “Brutality and possible gruesomeness (must be treated within the limits of good taste).” What about the moment when the sergeant steps on Montgomery Clift’s hand? Is this shocking? Should the implication that Sinatra was murdered by the sergeant have been censored because the sergeant represented “duly constituted authority”? What about that knife fight between Clift and the brutal stockade sergeant?

This knife-fight sequence, incidentally, edges warily around one part of the section “Crimes Against the Law.” Subhead (a) under “Murder” notes: “The technique of murder must be presented in a way that will not inspire imitation.” While Clift’s knife technique is shown graphically, the actual killing takes place out of camera range. But the same scene clearly violates Subhead (c): “Revenge in modern time shall not be justified.” True, Clift dies in the end, but not because he killed the sergeant. Should this drama have been presented in a different way?

5. MISS SAPRE THOMPSON

This picture is a fine lesson in ways to outwit the code. Reverend Davidson, a missionary in the original story and play, becomes Mr. Davidson, a blue-nosed reformer, merely the son of a missionary. This had to be done to satisfy Subhead 2 under “Religion”: “Ministers of religion in their character as ministers of religion should not be used as comic characters or as villains.”

How about Sadie’s costumes and gyrations? Jane Russell and Debra Paget got censored, but Rita got by, chiefly because the camera frame stops at her waist, leaving hip movements to the imagination of the audience.

Then there’s the Code’s word on “Locations.” Only one location is listed, and it’s just what you’d expect. “The treatment of bedrooms must be governed by good taste and delicacy.” Remember Sadie lying on her bed, holding the marines spellbound with her blues song? Is it adult to say this shouldn’t be a part of a screenplay? Or should the code be altered?

6. MOGAMBO

This remake of “Red Dust,” with Clark Gable and Ava Gardner, has provided entertainment for millions. But how did it get through the knothole of General Principle No. 2, calling for allegiance to “correct standards of life”? Look at the plot.

Ava has been invited to Africa by a maharajah (who’s never heard of Mrs. Grundy or chaperones) and has then been stood up. She falls into a casual relationship with hunter Clark Gable. (“Illicit Sex . . . must not be . . . presented attractively.”) She loses him temporarily to Grace Kelly, the wife of a member of the safari. (“The sanctity of the institution of marriage and the home shall be upheld.”) Should screenplays dealing with these subjects be banned?

7. STALAG 17

Bill Holden gives one of the year’s finest performances in this wry comedy spiked with melodrama. Yet the hero, in his very personality, violates the “correct standards of life” principle. He is, essentially, a heel interested in his own preservation and comfort, not in heroic self-sacrifice. He makes book on the escape chances of fellow POW’s, induces them to gamble (to his profit), and he sells them peeks through a telescope at female prisoners in a delousing chamber.

When his barrack mates suspect him of being an informer, they go in for code- banned “brutality” by beating him to a pulp and promising death for further informing. The death of the real informer at the picture’s close violates the same taboo.

8. HOW TO MARRY A MILLIONAIRE

This colorful investigation of the romances of three ambitious models raises cain with “correct standards of life.” First, Lauren Bacall secures the Park Avenue apartment which is to serve as base for husband-and fortune-hunting operations by shameless misrepresentation. Next, she sells the furniture (pure theft) for operating capital. Betty Grable goes off to

Maine with a married man, thinking that she is to attend an Elks’ shindig, and she is punished for this nonsense by falling victim to measles and by falling in love with Rory Calhoun.

Marilyn Monroe is fairly well-behaved in this film, but in “Niagara” she kidded the pants off Subhead 1 under “Costume”: “Complete nudity is never permitted. This includes nudity in fact or in silhouette.” The shower. at the tourist cabin had a translucent (not transparent) partition, but did anybody think Marilyn was bathing with her clothes on?

9. SHANE

Held high in the regard of public, critics and Hollywood, this picture would seem—offhand—to be supersafe from a censorship standpoint. Yet it smashes the general principle covering “Law”: “. . . nor shall sympathy be created for its violation.” “Shane” ignores another caution: “The technique of murder must be presented in a way that will not inspire imitation.” Anyone can fire a gun; moreover, Alan Ladd is shown teaching little Brandon De Wilde how to handle a shootin’ iron.

Think what an exact observation of the Code would do to that mainstay of the industry, the Western. Says the Code’s second supplementary warning on crime: “Action suggestive of wholesale slaughter of human beings, either by criminals in conflict with police, or as between warring factions of criminals, or in public disorder of any kind, will not be allowed.” Tenth warning: “There must be no scenes, at any time, showing law-enforcing officers dying at the hands of criminals.”

Do we only imagine that we see on the screen gunslingers bush-whacking sheriffs, posses battling mobs of rustlers, ranchers and homesteaders fighting range wars, rival bandit gangs shooting it out? All this is contrary to the code—but is it really wrong?

10. JULIUS CAESAR

Even Shakespeare must be given generous concessions to get him past the Production Code. Practically all of this play would have to be refused consideration if “correct standards of life” were always adhered to on film. The story deals with the assassination of a head of state. It depicts that assassination graphically. (“Brutal killings are not to be presented in detail.”) It shows the corpse clearly. (To be avoided: “possible gruesomeness.”)

The lovely silhouette shots of Deborah Kerr and Greer Garson in their filmy nighties (what’s the Latin for nylon?) are a welcome distraction, but they find a happy idea, rather than a warning, in Section 5 under “Costume”: “Transparent or translucent materials and silhouette are frequently more suggestive than actual exposure.”

Laurence Olivier’s “Hamlet,” currently being revived, is an absolute dictionary of Production Code don’ts. It even hints strongly at one theme so far out of bounds that the Code formulators didn’t think of mentioning it. But the nine men of the Breen office understandably seem to make special allowances when a classic comes up for approval.

There’s the record: ten important pictures, all ten made in direct violation of the code, yet only two unadorned by a Code seal. Do you believe the Code should have been applied strictly in every case? Do you believe the Code should be revised to allow a wider range of movie material?

When the public speaks, Hollywood listens. Your answers to the censorship questions on page 45 may affect the future of your favorite entertainment. Vote today! Mail your ballot today!

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE MAY 1954