All In Her Lifetime—Betty Hutton

Betty couldn’t sleep. The Michigan pictures had arrived that day, and all evening she’d been poring over the faces of old friends. They swung like bright bells through her mind, ringing back five fabulous days, ringing the past alive, too.

The scenes kept shuttling, fading in and out. From triumph to misery, from heartbreak to acclaim. Five days of honor and royal welcome. Bespangled carpets flung out for the home-town girl who’d become a movie star—for her mother who’d worked at the Chrysler plant in Detroit. Five days of cheers and tears, of thrills and laughter—a tour of glory and an emotional binge.

And always in the movie star’s shadow walked a child, invisible, who’d smashed her small fists against walls of hopelessness. “You wait, Mom, someday I’ll get you out of this. Someday I’ll buy you a fur coat down to the ground. Someday I’ll be a star—”

AUDIO BOOK

Nothing seemed less likely. Mom had drawn her close, to hide the thrust of pain. Betty pulled away. “You believe it, don’t you, Mom—?”

“Sure, honey, I believe it—”

“That’s good, because it’ll happen. And you know why?” Blue eyes blazed into her mother’s. “I’ll make it happen—”

She’d made it happen—from beerhall to band to night club to Broadway to movies, her indomitable spirit never wavering. There had been many payoffs. But these five days stood alone, if only because her mother had shared them. . .

The idea had sprung fullblown from some promotional brain at Paramount, “We want to premiere ‘Let’s Dance’ in Detroit, Betty. And we want to key the whole thing around your mother.”

Yelps from Betty. From Mom, who up to now had watched from the sidelines, “Oh, Betty, d’you think I can—?”

“Mom, we’ll doll you up like Mrs. Astor never dreamed of. Start dancing now, because you’re the belle of this ball. Me? Don’t be silly. I’m just along for the ride—”

Things started buzzing at the Detroit landing field. Chryslers packed end to end. Banners this high: WELCOME, BETTY HUTTON AND MRS. MABEL HUTTON. Flashbulbs popping. People falling all over each other. Mabel falling on the neck of her old forelady. . .

“Remember me, Betty?” Betty whirled. Mr, Miller, principal of Foch Intermediate. Remember him! She must have spent more time in his office than in the classrooms. Smiling, he handed her a couple of tattered textbooks. “Take a look at these. I thought you might like to keep them as souvenirs.” In her own childish scrawl on the flyleaves: “I love J. S.”

“Jack Smiley!” she whooped. “I bet he’s married now and has fifteen kids.”

“Last time I heard,” said Mr. Miller, “only five—”

. . . Into the cars and down to City Hall, where Mayor Alfred Cobo gave them the keys to the city. On to the Book-Cadillac. Betty’s glance caught her mother’s. Dozens of times they’d passed this same hotel, and the scrawny kid would always linger, awestruck. “Oh, Mom, can’t we just go in and walk ’round the lobby?”

“Honey, look at our clothes. I wouldn’t dare—”

Now the hotel was plastered with welcome signs for them. Now the presidential suite was reserved for Betty, and Mabel was given a beautiful suite to herself. With Mabel in a tizzy of ecstasy, and calls coming in from her old pals at the factory.

Betty was trying to assemble herself when the phone rang. Mom’s voice sounded strangled. “Drop everything, and get right over here. Fast.”

Betty sprinted through the corridors, opened the door, plunged headlong into the waiting arms of Cele and Bub . . .

Cele still works for Chrysler. Bub’s retired because of a heart condition. Mom and Cele, spitting tacks together in the upholstery department, had become close friends. They had moved into a basement apartment with Cele and Bub. “We’ll split the rent,” said Cele. “Be easier on all of us—” Marion and Betty shared the second bedroom, Mom slept on the living-room couch. She and Cele took turns cooking. The girls did the dishes and, after school, the laundry. Betty found herself an extra job. At $5 a week, she washed and cleaned for a family up the street. Unless they reached starvation point again, this fund was untouchable. She was saving it up to buy a dress to perform in.

You might smile to yourself—and it wasn’t a happy smile—but outwardly you had to go along with this kid who held fast to the conviction that someday she’d need a dress to perform in. Bub was head of the American Legion in Detroit. “Will you take me along, Bub? Will you let me sing for them?” He’d tip the crowd off, so they’d blister their hands, clapping. Night after night Cele would dance with her. All Cele craved after dinner was to rest her bones. But here’d be this hungry little face peering up at her. “How about it, Cele?”

You couldn’t resist her. “Okay, kid. Start the music.”

“Gee, thanks. I wouldn’t bother you except I need training. You can’t be a star unless you know how to dance.”

. . . Now Bub was holding her off, surveying her. “The little crumb always said she’d do it, and she did it.”

“Tell me the truth, Bub. You never believed it.”

“Honey, as God’s my witness, I thought you were nuts.”

The premiere Thursday night. Mom all gussied up in the beautiful black gown Paramount made for her. Her hands, well-groomed now but bearing their scars. Almost more than anything else, those hands, bleeding and swollen where they’d missed the tacks, would eat into young Betty Thornburg’s soul. She’d drop her face into them and sob, “Oh Mom, someday—”

“I know, baby, I know.” And one battered hand would creep up to caress the stricken head . . .

There she stood in the wings now, hands and all shaking like crazy. Betty threw her a grin and went on. The place was packed to the rafters, with all the factory workers down front. They rocked the joint. Their memories went back with Betty’s, weaving bonds between them. She sang for them as she’s never sung before and may never sing again. With the ache of old sorrows, and a heart of thanksgiving.

At last quiet fell, and a kind of hushed waiting for the big moment. “I want to introduce someone who needs no introduction to many of you. Without her, none of this would have been possible—” She smiled toward the wings. “Ladies and gentlemen, friends and neighbors—my mother!”

Poised as though she’d been born a Barrymore, Mabel made her first appearance on any stage and took her first bow. Betty alone heard her quaver through the thudding roar: “What am I going to do?”

“You’re going to sing.”

“I can’t—”

Betty leaned toward the orchestra leader. They had to play the first bars over and over before she could make herself heard. “My mother’s going to sing ‘Shine on, Harvest Moon,’ and you’re all going to join in the second chorus.”

Mabel’s voice broke at first, but in a couple of seconds she was going strong. Waves of warmth washed over them from the audience. Betty was their girl, who could do no wrong. Mabel belonged to them more closely still. She’d worked with them at twenty-two cents an hour, helped organize the union to get them better pay. And because the fairy tale of America had come true for these two, it had come true in a way for all of them.

The song done, Mabel stepped toward the footlights. Like a veteran, smiling and composed, she waited for the noise to die, then said her brief say. “I want to thank you for the happiest night of my life. And I want you to know that I take no credit for this. This is God’s work.” With which, she marched off.

They shouted themselves hoarse and forced her back. Betty took her hand. “I have no words to tell you how we feel. But I have a song. Forgive me, Paramount, because this is from a Metro picture.”

It was of course “There’s No Business Like Show Business.” Through Betty’s released emotions it poured, and swelled from her throat. For who knew better than she the thrilling reality of every word?

She was back at Billy Rose’s Casa Manana—not part of the show, just singing with Vincent Lopez’s band while the people danced. Good enough, most girls would have thought, for a sixteen-year- old who’d been getting nowhere fast till a year ago. But not good enough for a wildly impatient Betty, who had no use for crawling from rung to rung. Her idea was to fly.

The regular bill featured Lou Holtz among others. Holtz used to come down from his dressing room to watch her. Having watched his fill, he sauntered in to the boss. “Ever take a look at the dame who sings with the band?”

Mr. Rose looked, listened and sent for the Lopez thrush. “I’m putting you in tomorrow night as a warmer-upper.”

The tone was casual, its effect was anything but. In a trance Betty went home to Mom, who’d quit her job, sacrificed her treasured seniority at the factory to take a gamble with her girl. The girl’s face was solemn. “This is it, Mom, live or die.”

In the dressing room next night, they knelt down and prayed together. It’s a Hutton tradition. Their faith in God is simple and unquestioning. Any crisis finds them on their knees, laying their problems in the lap of God.

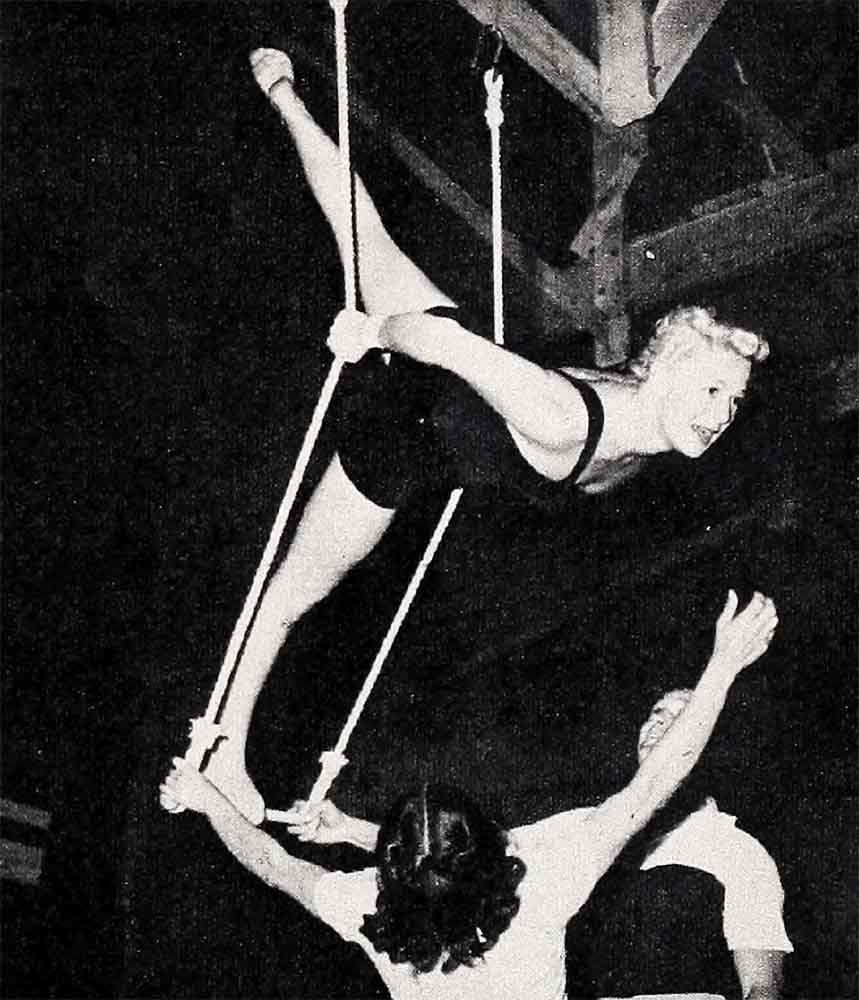

Betty made her entrance. In the sea of faces, she sought her mother’s and found it. Mom’s thumb and forefinger lifted in a solid okay, and Betty’s spirit soared. Plunging into “A-Tisket, A-Tasket,” she let herself go for the first time in a style that has come to be the Hutton trademark. A small whirling dervish, she bounced in and out among the musicians, assaulted the mike, tore the stage apart and wound up swinging from the curtain. Catching her infection, the audience went mad and refused to let the next performer go on. The next performer happened to be Mr. Holtz. After three encores and prolonged salvos of applause, he shut them up by leading her out and indicating that he had something to impart:

“Ladies and gentlemen. Tonight theatrical history has been made. You, the public, have recognized a new talent, and so a star has been born. This, ladies and gentlemen, is show business.”

The star spot on any bill is next to closing. That was Betty Hutton’s spot the following night.

HER head shifted against the pillow. Her memories shifted like a movie montage. Back to the tour and Friday morning in Detroit. Back to Foch Intermediate, where she’d once been a problem child and was now a celebrity, come to sing to the kids. Back to the arms of Miss Jones. She couldn’t get to Miss Jones fast enough . . .

. . . Deborah Jones had been her home room teacher, her champion, her light in darkness—one of those rare persons who could see through a child’s defensive crust to its source. If many of the children were poor, Betty was poorer. Her clothes, spotlessly clean, were patched and worn, and her pride streamed like a banner in the breeze. With an active loathing, too fierce to be contained, she loathed her poverty. Her impulse was to strike out at an unjust world, and her more fortunate schoolmates represented that world. You had only to appear in a pretty new dress, and while pain twisted through her, she’d kick you in the shins and growl: “Meet me outside—”

She was always in trouble. Miss Jones remained her compassionate friend throughout “Don’t you see the child’s all mixed up?” she’d plead with the others. “She’s not bad, she’s unhappy. Her emotions are too strong for her. She’s simply battling for life.” And to Betty, smoothing the hair from a tearstained face: “Someday you’ll have lovely clothes, dear. Then you’ll find out they’re not as important as you think. Nothing really matters except what comes from inside. And inside, you’re one of the finest people I know—” Betty worships her. To the last day of her life, the name of Deborah Jones will be a light in darkness . . .

The Green Tree was Betty’s idea—an unscheduled stop on their way to the Chrysler luncheon. “I’ve got to show you this beerhall where I used to sing.”

Her heart gave a little lurch as they crossed the threshold. She might have been eight again, for nothing had changed. Same old chairs in the same old spots, same old piano, same old threadbare rugs. Same guys—anyway, they looked the same- sitting around with their sleeves rolled up. Same friendly “Hiya, Betty—”

. . . During factory layoffs, with an income dropped to minus, Mom used to bring her here. Partly because they had to eat, partly because Betty gave her no peace. “Please, please, Mom, let’s go, and I’ll sing for them and earn money.” Her repertoire consisted of “Dinah,” “Lazybones” and “Some of These Days.” At the close of each number, the customers would throw nickels and dimes on the floor, and she’d pick them up in a hat. This was no case of charity, but of give-and-take in a spirit of fellowship. The customers were all factory workers. Betty was Mabel’s daughter, and Mabel was one of them, fighting to get them more dough. Why shouldn’t they help when she was on her uppers? Besides, the kid gave them their money’s worth. Look at her! Half-pint of pluck and fire and a voice, knocking herself out to entertain them. “Yeah, Betty!”

Betty blinked and came to. She was no longer eight and nobody was throwing nickels and dimes. “Hiya, fellas. Just wanted my pals to see where they raised me from a pup.”

On the tour of the plant Betty was an incident. “Where’s Mabel?” they yelled, and hoisted her to their shoulders. Took her to the upholstery department. Gave her a hammer—the kind she used to hit tacks with. Showed her the new car Betty had picked for her. Queen Mabel! With Miss Hutton of Hollywood trailing happily along.

Then the executive dining room and a luncheon by Chrysler’s top brass to honor the Huttons.

They made speeches to Mabel, and as Mabel rose to reply, Betty prayed alone. “Oh God, please, please, God, don’t let her make a mistake.”

At the age of nine, Betty’s mother had been sent to work, and her formal education came to a close. Understandably, therefore, she sometimes fails to stick to grammarbook rules. That Betty should have cared so much may seem out of proportion. The fact remains that she’s passionately protective of her mother. Shaking inside as Mabel rose, she prayed.

Mabel gave out with a speech that fractured them. She spoke briefly, pointedly and in the purest King’s English. Closing, she turned to her hosts. “Gentlemen, when I was fighting for a union in your factory, had I known what wonderful people you are, I wouldn’t have been bitter. You must be wonderful people, or all these friends of mine wouldn’t have been working for you all these years.”

On this note she sat down, while bedlam broke loose and Betty’s tears overflowed. She cried even harder when the director of the junket repeated what Mabel had said to him. “Have I done anything wrong? Did I make any blunders? Did I embarrass you in any way? Don’t red-apple me, I want the truth.” He told her the truth. “Thanks, Jerry. You’ve taken fifteen years off my life.”

Saturday in Lansing, Riding in the parade with Governor Williams. Watching them hang a plaque on the old house: “This is where Betty Hutton lived.” Sitting with Mabel between the Governor and the Mayor at the Red Stocking Luncheon—to kick off the drive for such underprivileged children as Betty had been.

After all the speeches were done, a minister rose—for what they supposed would be the benediction. It was a benediction. He prayed for Mabel and Betty. He thanked God Who had given them strength and courage to clear the narrows, and Who had led them to a place where Betty could bring gaiety to a troubled world. Mother and daughter gripped hands, humble, grateful and more profoundly moved than by all that had gone before.

And of all places—in Lansing, which they’d left in a hurry. Not to put too fine a point on it, they’d been virtually thrown out. Mom ran a blind pig in the very house where the plaque now hung. Her husband had left her. Somehow she had to put food in the mouths of her kids. People came for beer and gin. The beer was okay, but the gin was illegal, and one night the cops arrived. Friends stalled them long enough for Mom’s trembling fingers to bundle the children up. Three forlorn figures, they fled out into the snow and made their way to Detroit. . .

Now the two who had come back sat there, heads bowed under the lovely light of God’s blessing.

In the old days, Lansing had provided another blessing—Aunt Cuma. On the Sunday after the Red Stocking luncheon there was a family get-together at Aunt Cuma’s. She cooked for twenty. The dishes towered to the ceiling. Betty shooed them all out of the kitchen, and washed every last dish, same as she used to do. Left the kitchen immaculate, same as she used to do.

Cuma was one of Mom’s most loyal friends. She was also the one person who used to say: “Take it from me, that kid’s going places someday. Nothing’ll stop her.”

“Need any training?” Aunt Cuma asked that Sunday, as Betty appeared rolling her sleeves down.

“Sure. Let’s sing—”

“Let’s dance, you mean—”

“Let’s do both.” So they did and had themselves a ball.

. . . Battle Creek on Monday. They hadn’t much time in Battle Creek, but they saw Aunt Jessie and Uncle Ray and the cousins.

Jessie was Mabel’s real aunt, Betty’s great aunt, and she’d always made much of Marion. Betty felt like the outsider, looking in. Marion went to Battle Creek every summer and returned well outfitted for school—new dresses, new shoes. Betty, two years younger, wore the cast-offs with a sense of burning injustice and terrible envy.

“I’ve read some of the stories,” Aunt Jessie said, “and they hurt me. You were such a frantic, restless child, Betty. Marion was quiet. She liked our quiet ways. You never cared for them.”

“I understand. I’m old enough now to understand lots of things. But there’s one thing I’d like you to understand too, Aunt Jessie. All I ever really wanted from you was love.”

Her aunt’s eyes filled with tears. “I loved you, dear. Maybe I didn’t know how to show it. But I do now. This is the first time since my daughter died that I’ve ever gone out. The first time in fifteen years.”

Betty pressed her warm cheek against the older one. “Thanks for coming, Aunt Jessie. And let’s forget all the rest—”

She was three when they left Battle Creek, six when they took flight from Lansing, not quite fifteen when she stormed out of Detroit. “I can’t stand this place. I can’t stand school, I can’t stand the way we live, I’ve got to get out.”

. . . She’d been singing at the Graystone Ballroom, telling everybody she was eighteen. Among the few who fathomed the desperate urgency that drove her was Charlie Stanton, manager of the place. He was kind to her, called her Tomato, earned her deathless gratitude by arranging an audition with Tommy Dorsey .

Betty was beside herself with excitement. Charlie wasn’t excited. An expert driver, he guided the car carefully as they started out for a place they never reached. Somewhere along the icy road they skidded, and hit a chicken truck. He died within ten minutes. The car looked like a flattened accordion, but Betty escaped with a concussion.

The concussion was nothing to the emotional shock. Her friend was dead, her chance was gone, and the accident made the local front pages. Once she was well enough to go back to school, she found herself marked, at best—eyed with curiosity, at worst—shunned by the holier-than- thous. Tsk-tsk, a girl who got her name in the papers! It brought years of seething rebellion to a boil. “I’m through with this town, Mom, and this kind of living. I’m going to New York.”

To Mabel, hampered by her own lack of education, a high school diploma was the passport to a full life. Betty’s clamorous pleas always shattered against that rock. “After you finish high school, you can try your luck. You’ve got to finish high school first.” Now Mabel could fight no longer. Betty’s will to go defeated her own will to keep her. A group of ambitious kids had formed a unit, with which they planned to stampede Broadway. Betty went along. Strangely, Broadway refused to be stampeded or even to take note that they were alive. A big-hearted agent forked out enough to send them home, and Betty was back where she started.

Disappointed, of course, but not for a moment disheartened. Still looking for spots, still looking for chances to sing. By now Marion was singing too. One night her boy friend picked Betty up to call for her sister, who was working at The Nut House. They were a little early. Passing the Continental Betty said: “Let’s go in a minute. Maybe they’ll let me do a number.” The management obliged. A man at one of the tables sat and listened, and whispered something to the waiter. Presently the girl was threading her way toward him, fainting inside. “Sit down, Miss Hutton. How would you like to sing with my band? I’ll pay you $65 a week.”

This was more money than she’d ever heard of. But she’d heard of the man all right. His name was Vincent Lopez.

A year of travel with the band. The night at Casa Manana when the heavens spun. Then vaudeville and “Two for the Show” and more vaudeville, and Vincent suing to keep her with the band, though he might as well have sued a soaring lark.

One day she paced the floor of Abe Berman’s office, explaining her troubles. He fought the suit and won it for her, but that’s incidental. Berman was Buddy De Sylva’s lawyer too. “Do you know De Sylva?” he asked.

“Not to speak to. But I’ve seen him around. You can’t forget his face—”

“He wanted you for ‘Louisiana Purchase.’ They told him you weren’t available.” He picked up the phone and called De Sylva in Florida. “I’ve found your Florrie for ‘Panama Hattie.’ Whom do you think? The girl you’ve been crying for. Betty Hutton.”

“Sign her,” said Buddy.

. . . Not long ago a story appeared that took note of Betty’s gratitude to De Sylva. It went on to say that, grateful or no, she never let emotions tangle with professional ambition and that, during the last year of his life, Buddy refused to speak to her because she reneged on a picture she’d promised him.

Like all half-truths, this story masks the real truth. De Sylva was to Betty the kind of friend you find once in a lifetime. After the success of “Panama Hattie,” he went to Paramount as head of production, and asked her to make a picture test. She was riding high on Broadway and she was stubborn. “I’ve made tests, Buddy. They dyed my hair black and stuck me into drah-ma. I’m through with tests.”

His faith in her was such that he talked Paramount into signing her without a test for “The Fleet’s In.” Her movie history needs no re-telling here. It’s been rung up merrily on the box office of the world. If De Sylva’s contribution is less well known, that’s not because Betty hasn’t shouted it to the housetops. “He just taught me the picture business, that’s all, from A to Z and all the letters in between. He never failed me—”

When he fell ill, Betty went to the hospital. Except for his wife, no one but Betty was admitted. It was then that she gave her promise. “As soon as you’re well again, Buddy, I’ll make a picture for you.”

But he had a second seizure that affected his brain. No longer the acute-minded man of his normal days, he sent Betty a script that made her weep for him. Heartsick, she called his wife. “Have you read it, Marie? Then you know how bad it is. I’ll do anything for Buddy, including a lousy story. But for his own sake, he shouldn’t make it like this. Can’t we get someone to fix it up?”

“Listen, Betty, if it were the greatest picture in the world, he still couldn’t make it. He’s far too ill. Forget it.”

She was never able to reach him again. Which proved to Betty that her friend, whose large spirit held no room for pettiness, was gone. The real Buddy would have talked things over with her. The real Buddy died with the stroke that went to his brain. In the warmth of her memory he’ll never die.

“Someday I’ll be a star,” the child had l» cried, struggling like a little tiger against the bars of circumstance, fighting her hard-pressed way out of darkness toward a vision, radiant and remote. “I’ll make it happen—” It was a pledge to herself, and she’d kept it in spades. Dancing star now with Astaire. Singing star of “Annie, Get Your Gun,” for which she wins the Photoplay Gold Medal for the actress giving the most popular performance of 1950. About to be starred under Cecil B. De Mille, the greatest showman of them all, in “The Greatest Show on Earth.”

“I’ll do Annie for nothing,” she told her agent, tight-lipped, when it looked as though that super-deal might fall through. Paramount naturally nixed this proposition, though left to herself, Betty would have made it good. She still can’t get over the wonder that, for doing something you couldn’t keep her from doing, she’s achieved economic security beyond her craziest dreams. Show business had lavished the gifts of life upon her. But one gift lay beyond its power to bestow. . . .

In the nursery Lindsay and Candy slept—her children and Ted’s. What every woman wants, Betty wanted too—happy love and marriage. These had escaped her.

It was nobody’s fault. Searching the past, she could blame neither Ted nor herself—except that they should have waited to know each other better. But who waits when love strikes? It had been a whirlwind courtship in Chicago and they laughed at the crepe-hangers. Betty added a room to her new house. Ted started a branch of the Revere business in Santa Monica, so they could live happily ever after.

Ted was the product of a well-to-do. conventional background. He couldn’t understand Betty’s world of the studio. She couldn’t understand his world of business. At first the clashes were inconsequential, for they always made up. And the children, to whom both were devoted, did much to hold them together for a while. But under continuous conflict of temperament, the illusion of love broke down. Last March Betty filed for divorce. Ted returned to Chicago.

In her teens, when it’s normal for a girl to date, Betty was too busy carving a career to waste time on boys. Maybe that was the trouble, she decided. Maybe she’d missed out on something important, maybe she ought to learn about men. So she started dating, hitting the night spots, living it up. And found the whole business as empty as a gourd. Betty’s a complex character. She revels in the excitement of her profession and yearns at the same time for domestic anchorage with a good man.

Ted Briskin’s a good man. His instincts are kindly, decent, clean. Betty continued to value that aspect of him even when she stopped being in love with him. Last July she went away to set her mind in order, then flew to Chicago where she and Ted talked things over. They agreed to try it again. For their own sakes, and especially for the children’s. Ted would stay in Chicago. He belonged there as surely as Betty belonged in the picture business. But he’d fly out for weekends and holidays, and when Betty wasn’t working, she’d bring the children to him.

It was a valiant effort, foredoomed to failure. No marriage can thrive that keeps husband and wife 2,000 miles apart most of the time. One day last December they faced and accepted this reality. In January Betty filed for divorce again. Ted’s free to see the children as often as he likes. To Betty, it would be little short of a crime to cut them off from his love or deny him his paternal rights. As she explained it to Lindsay: “Even though he doesn’t live here any more, he’ll always be your daddy and you’ll be his little girl. He’ll always love you and he’ll always come to see you—”

She’s too honest with herself to call it a happy solution. It was just the only solution possible. And the shadow of loneliness remains. . . .

Awake in the darkness, she’d come full circle. From now to then and back. This was her life. A strange and wonderful life. A regular storybook life—except that the wrong prince had kissed the wrong girl. Well, you can’t have everything. Maybe someday the right prince would come along. If not—

Slipping out of bed, she laid that problem too in the lap of God. Then she fell asleep.

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE MARCH 1951

AUDIO BOOK