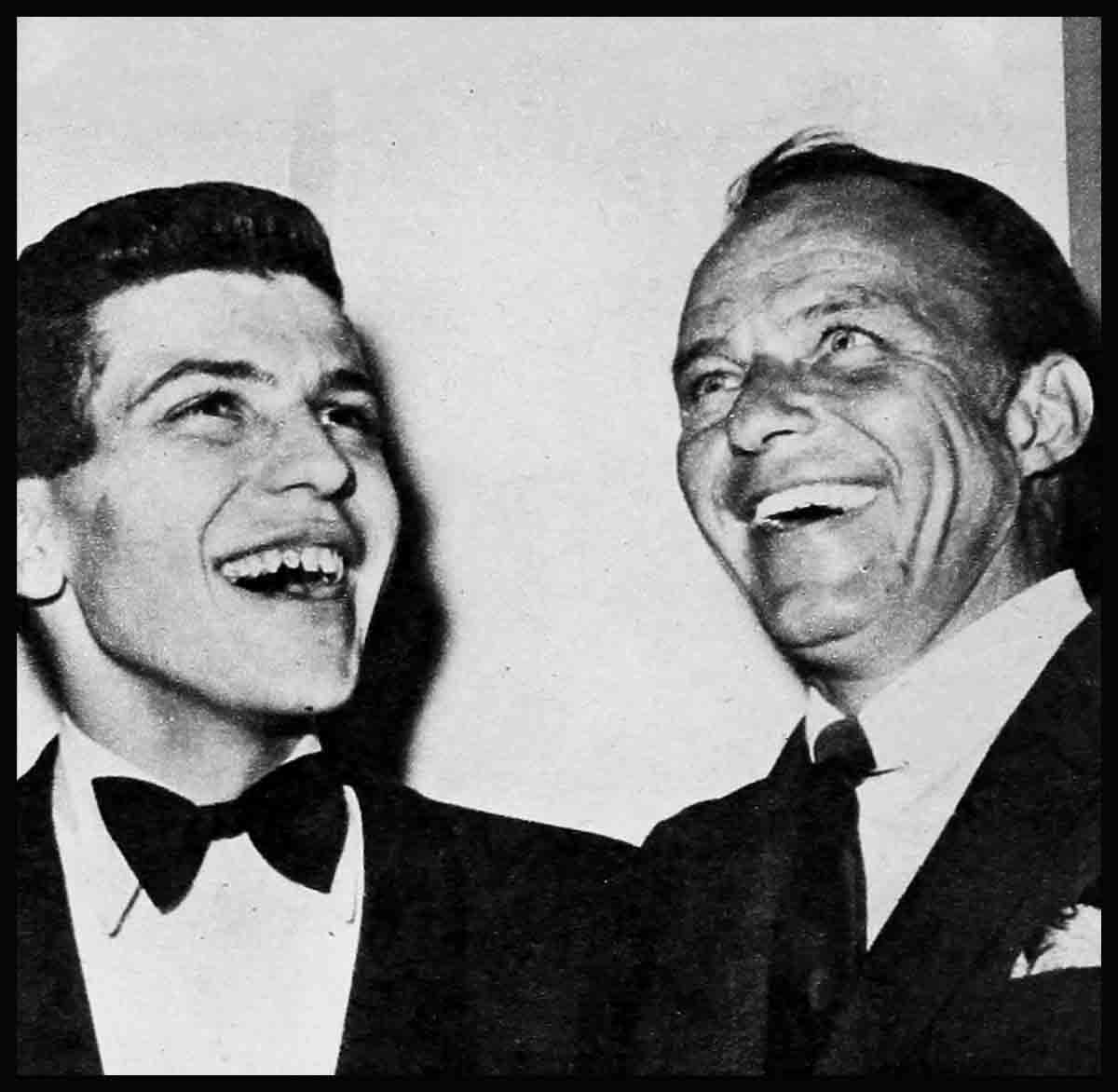

Frank Sinatra Tied To Gangsters! Son Defends Father . . .

As he walked out onto the stage I of the Royal Box at New York’s plush new Americana Hotel, the twin spotlights hit him smack in the eyes. It was a little like being in a police lineup, except that there were hundreds of strangers out there in the dark room instead of a handful of detectives and cops, and they were not there to pick him out as a criminal suspect, but to judge him as a singer. Or were they?

He was Frank Sinatra, Jr., and this was his opening night in the Big Town. His previous opening night performances—in Vegas and Atlantic City and all those other places—had been strictly from Podunk. This was the big-time; tonight was for keeps: win the works or go for broke. But surely he didn’t rate forty-five photographers and reporters—those guys milling around in the lobby. Besides, they hadn’t beaten a path to his dressing room and they weren’t wasting much of their film on his picture.

Most of the crowd out there behind the blinding blaze of the spotlight (as Milton Berle used to say, you knew someone was there because you could hear breathing) had showed up primarily because they were curious to see if he could make it big in his own right, or if he were just a blurred carbon copy of his famous dad. Or had they?

He knew they were there, all right, not because he could hear breathing, but because he could hear whispering—the buzzing of tongues. And, even if he couldn’t see their eyes because of the spotlights’ glare in his own, he knew that they weren’t fixed exclusively on him. They were moving back and forth like spectators’ eyes at a tennis game, turning from empty table at ringside to singer on stage: table to stage to table to stage—moving eyes keeping pace with wagging tongues.

It wasn’t just that his father hadn’t arrived yet for his son’s opening night. It wasn’t just that the empty table—reserved for “Frank Sinatra and Party”—stood out like a sore thumb in the over-filled room. It was just—it was just that they were saying that his own father was afraid, afraid to face the music.

No, not the music of Tommy Dorsey’s orchestra which was backing him up tonight just as it had backed up his dad twenty years ago, except that Tommy was dead and now Sam Donahue was giving the beat. It was the bitter music contained in those headlines in the papers out in the lobby, the same headlines that had brought the photographers and reporters on the double to get a statement from his dad if he showed and that had hyped up attendance here to the overflow point: Sinatra In Hot Water Over Ganglord’s Nevada Visit . . . Sinatra on the Spot—May Lose Gaming License—Accused of Playing Host to Gangster in Nevada . . . Sinatra in Jam over Hood Pal. . . . It was just—aw, nuts!

Frank Sinatra, Jr., nineteen, a huskier version of his famous father, cigarette held casually in his right hand (did the fingers tremble a bit, or were they just responding to the beat of the music?), closed his eyes (was this his usual stance, or was it to blot out the image of the empty table visible on the outer perimeter of the ring made by the spotlights?), leaned his dark-haired head back, opened his lips and sang. The words, the phrasing, the shading, the vocal mannerisms were similar to his father’s; but the emotion, the feeling in his songs, was shyly, uniquely his own.

As long as he kept singing, as long as he kept them listening to him, their eyes wouldn’t probe and stray and their tongues wouldn’t pry and wag. As long as he kept them listening to him, they wouldn’t buzz about the headlines. . . .

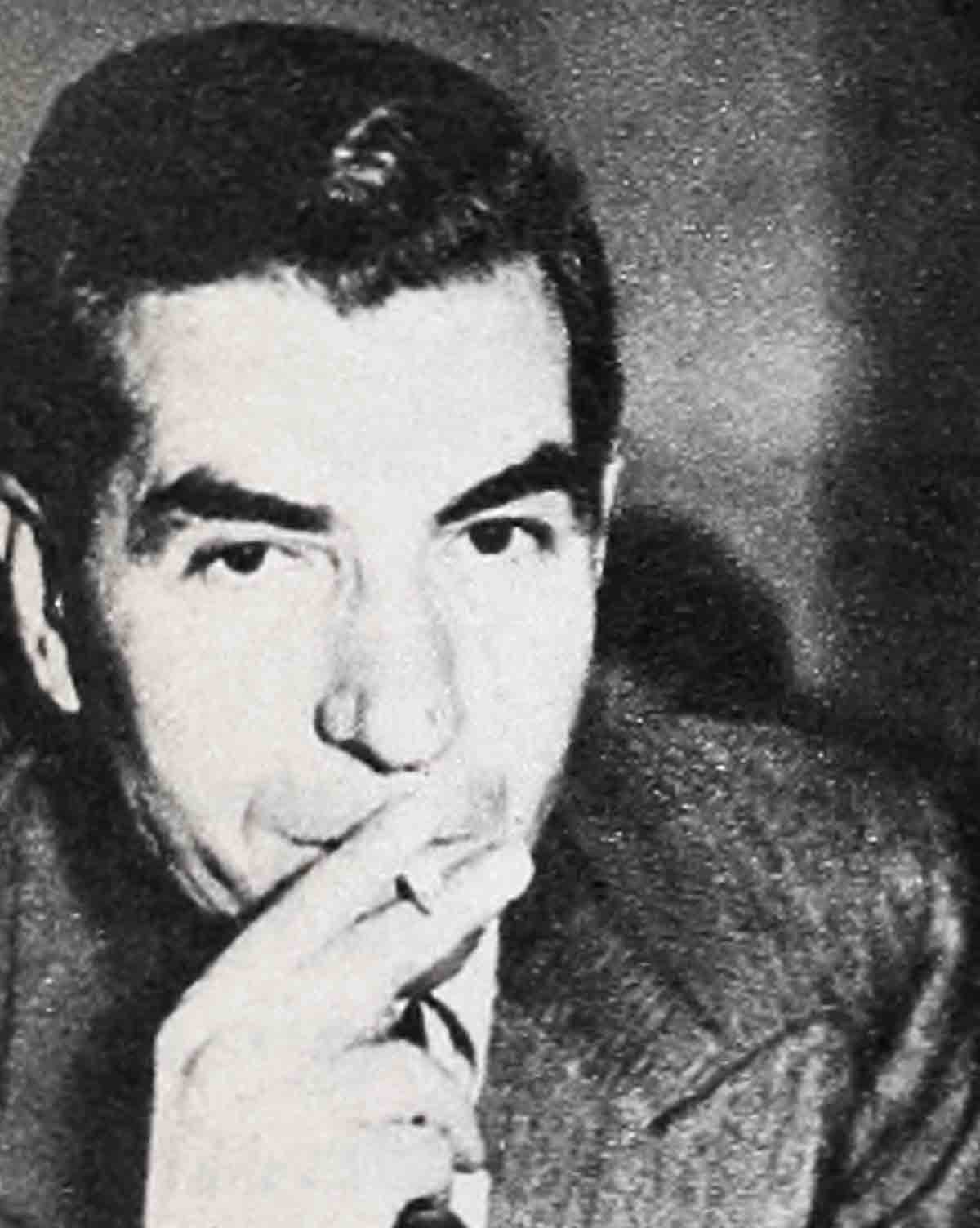

The Charges: A formal complaint, issued by the Nevada Gaming Control Board, charged that Frank Sinatra knowingly played host to a notorious underworld figure. That he had as his guest at his Lake Tahoe resort, the Cal-Neva Lodge, July 17 to 28, one Salvatore Giancana (also known as “Momo” and “Sam” and “Mooney”) of Chicago, who had been previously identified by the board as “one of the twelve overlords of the Mafia.”

Giancana is one of the eleven persons listed in the Nevada commission’s “Black Book,” whose mere presence in any gambling casino in that state is considered sufficient grounds for revoking the license.

Specifically, Sinatra was charged with allowing Giancana to stay at one of the chalets adjoining the casino. The complaint said “although chalet No. 50 at the time of the visit of Sam Giancana was registered to a female performer then appearing at the lodge . . . said Sam Giancana is known to have been entertained, harbored, and permitted to remain there and receive services and courtesies from the licensee (Sinatra). . . .” Gaming board chairman Edward Olsen, who filed the complaint, refused to identify the female performer.

It is known, however, that Giancana, fifty-four, thin and balding, was seen at the resort in the company of Phyllis McGuire, thirty-three, youngest of the McGuire Sisters who were performing at the lodge at the time the gang leader was there, and that he was photographed with her. Giancana, a widower (his wife Angelina died eight years ago and he is the father of three daughters), calls Phyllis “my girl friend.” He first met her at Las Vegas and since then, in addition to visiting her frequently at her New York City apartment at 525 Park Avenue joined her last year in London, where she and her sisters were performing in a club. Later, Sam and Phyllis toured Spain and Italy together. Although Interpol (the international police organization) keeps close tabs on Giancana when he’s abroad (just as the FBI checks on him constantly in this country), there are rumors that Sam and Phyllis (divorced in 1956 from TV announcer Neal Van Sils) managed to give the authorities the slip during their 1962 European trip and get married.

In any event, when Nevada investigators started nosing around the Cal-Neva Lodge last summer, it is alleged that Sam and Phyllis flew off to Frank’s Palm Springs ranch for a few days in the sunshine.

“Sinatra used vile language . . .”

Board chairman Olsen’s complaint further charged that when the singer talked to him (Olsen) about Giancana in a telephone conversation on August 31, 1963, “Sinatra used vile, obscene and indecent language, in a tone menacing in the extreme, (constituting) a threat. It was designed to intimidate and coerce the chairman and members of the State Gaming Control Board to drop the investigation,” Olsen said.

The board said Sinatra’s partners at the Cal-Neva—Henry Sanicola and Sanford Waterman—were blameless in the housing of Giancana. (Reportedly, Frank is in the process of buying out his partners’ interests in the lodge.)

The complaint also alleged that a Sinatra employee at the Lake Tahoe casino tried to bribe two gaming board auditors. It claimed that Paul d’Amato, listed on the Cal-Neva payroll as an “advisor,” “attempted to force money upon two audit agents . . . who were then engaged in their official duties of verifying the gross win at the gaming tables” at the club.

In asking that Sinatra’s license be revoked, the complaint asserted “Frank Sinatra . . . has for a number of years past maintained and continued social associations with said Sam Giancana while knowing his unsavory and notorious reputation, and has openly stated that he intends to continue such association in defiance” of Nevada gaming laws. (When Sam’s middle daughter, Bonnie [ then twenty-five ], was married in Miami Beach a few years back to the secretary of a Chicago Democratic politician, Frank was reportedly one of the guests; and, according to New York Journal- American columnist Dorothy Kilgallen, “When he (Sam) was involved with the Villa Venice of Chicago, which later was closed because there was a little gambling going on in connection with the night club [ although of course Frank and Sam didn’t know anything about it ] Frank persuaded members of the Clan, big names like Dean Martin and Sammy Davis, Jr., to headline at the Villa Venice at very reasonable fees.”)

The Stakes: Sinatra’s fifty per cent interest in the Cal-Neva Lodge and his nine per cent interest in the Sands Hotel in Las Vegas (he invested $50,000 in the Sands a few years back, an investment that has since increased in value seven times over) add up to assets of three million, five hundred thousand dollars in Nevada alone. (His estimated total wealth, accumulated during the past ten years since making a comeback in “From Here to Eternity” after sinking to a career and financial low, is $10,000,000.)

Loss of Sinatra’s license at the Cal-Neva would automatically, according to board chairman Olsen, amount to loss of license at the Sands. Not that Frank couldn’t unload his interests in both enterprises without suffering too great a financial loss, but psychologically and in terms of prestige it would be (to use one of Sinatra’s favorite phrases) “a kick in the head.”

The Beef: Who is Sam Giancana that his presence at the Cal-Neva should cause state authorities’ blood pressures to shoot up so high?

He is—according to stool pigeon Joe Valachi, now singing to Federal agents about underworld activity in the United States—the Chicago head of “Cosa Nostra” (“Our Business” or “Our Thing”), a loose confederation of gangs in at least eight states. Although when Valachi joined the organization in 1930 he took a blood oath (his finger was pricked) to die rather than betray it, he is in the process of “fingering” Giancana and a host of other ganglords.

Valachi’s information, added to that of the FBI, provides the following profile of Sam’s rise to gangland power:

• Suspect in three murders before he was twenty.

• Getaway car driver for the old Chicago 42 Gang under the leadership of Paul (The Waiter) Ricca and Tony (Big Tuna) Accardo.

• Draft rejectee in 1941 because of “strong anti-social trends and a psychopathic personality.”

• Ex-convict who did time for burglary and operating a moonshine still.

• “Enforcer” in 1943 for Accardo. Just before Ricca went to prison for ten years for a $1,000,000 movie extortion plot, he selected Giancana to be his avugad (or representative) while he was away. (The selection of Accardo was made at a meeting in Ricca’s palatial home in River Forest, a Chicago suburb, attended by Sam [ Golf Bag ] Hunt, Jake [ Greasy Thumb ] Guzik, Murray [ The Camel ] Humphreys, and the nominee himself.)

• Boss of the Chicago “family” of “Costa Nostra” in 1959, after Accardo was also indicted and convicted of income tax evasion. Accardo’s conviction was later reversed and federal “heat” was still on him. He became an “elder statesman” of the gang, and Giancana continued to reign supreme.

Anti-Sinatra: When word got out about Frank’s alleged association with Sam Giancana, the reprisals against the singer, verbal and otherwise, were both swift and discouraging.

Nevada’s Governor Sawyer declared his state’s gaming industry “must keep a clean house or get out.” He said the industry “cannot afford anyone who isn’t big enough to play by the rules,” adding that “threats, bribery, coercion and pressure would not be tolerated.”

Columnist Dorothy Kilgallen asserted that “show biz experts are betting that Warner Brothers will change the title of Frank Sinatra’s projected picture, ‘Robin and the Seven Hoods.’ Under the circumstances, it’s not so humorous.”

The president of two radio stations in Massachusetts and Connecticut, Lawrence Reilly, gave orders banning Sinatra’s records from the air, after the Nevada mess hit the headlines, on the grounds that “we don’t want to be identified with him.”

President of the United States John F. Kennedy, at the Inaugural Gala produced by Frank in Washington back in 1961, hailed the singer as “my good friend Frank Sinatra.” Now columnist Leonard Lyons reports JFK shrugged his shoulders when he “learned of Sinatra’s odd loyalties” and said, “He was Peter’s (Lawford) friend, not mine.” And columnist Charles McHarry reports that Sinatra now has trouble when he tries getting the White House on the phone.

There were others—people with long memories and a low opinion of Sinatra—who dredged up old charges (spread mainly by the late Lee Mortimer, New York Daily Mirror columnist) that many of Frank’s pals, over a number of years, are among the nation’s most notorious hoodlums.

These charges boiled down to the following: 1) Sinatra is the owner of stock in a Las Vegas gambling casino regarded by some as an underworld operation. Sinatra has been chosen by certain interests to take over the entire amusement industry. (Mortimer, April 5, .1960); 2) “Willie Moretti, alias Moore, kingpin of the Jersey rackets, and cousin of Joe Adonis, ‘discovered’ the struggling lad (Sinatra) in a Hoboken gym. . . . The mob got Sinatra a job in the Rustic Cabin, a Jersey roadside retreat, at thirty-five dollars a week.” (Mortimer, August. 1951); 3) Moretti (gunned down in the streets in 1951) threw two lavish weddings for the daughters of his cousin, mobster Frank Costello, at the Essex House in Newark. Later, Sinatra called his Hollywood independent film company Essex Productions; and the question asked is whether he had a financial interest in another Essex House in San Fernando Valley’s fashionable Encino; 4) In an article in the American Mercuryentitled “Frank Sinatra Confidential: Gangsters in the Night Club,” Mortimer alleged that in February, 1947, the crooner’s name appeared on a Pan American flight manifest from Miami, Florida, to Havana, Cuba, along with those of Joe and Rocco Fischetti, cousins of gangster Al Capone. Frank, Mortimer said, was carrying a “heavy suitcase,” and the three men were heading for a meeting with the international vice king, Charles (Lucky) Luciano. Mortimer continued: “The same week Sinatra and the flying Fischettis visited ‘Lucky’ in Cuba, the Feds reported that two million dollars in small hand bills had been delivered to Luciano ‘in the hand luggage of an entertainer.’ ” (Mortimer, August, 1951); 5) Sinatra, at twenty-eight, was grossing a million dollars a year. Were members of the Mafia brotherhood (the sinister underworld cabal) using him as a front and biting off huge chunks of his dough?

Pro-Sinatra: There were others—people with long memories and a high opinion of Sinatra—who countered these charges one by one.

They pointed out that while Frank had once said, “If it hadn’t been for my interest in music. I’d probably have ended in a life of crime,” he has the interest in music and he isn’t a criminal.

As for the specific accusations made against Frank in the past, they refuted them in order:

1) The Sands Hotel being an underworld operation—They quoted Rat Pack chronicler Richard Gehman, who in turn had quoted a “prominent Las Vegas citizen” as telling him: “It is hard to believe that a city so in the thrall of law-enforcement would tolerate mobsters unless they were so far underground they could not ever be detected.” Besides, as Frank is now finding out the hard way, there’s the watchful Nevada Gaming Control Board.

2) Sinatra as Willie Morett’s protege—They repeated Sinatra biographer Don Dwiggins’ exploding of this myth: “Mobsters don’t gamble on long-shots, and Sinatra was just that. The few dollars a week he was earning, or could earn, at the Rustic Cabin hardly seems worth the trouble to put in a fix.”

3) Sinatra’s financial interest in the Encino Essex House—It just wasn’t so, as policemen found out when they investigated.

4) Sinatra’s “friendship” with the Fischettis and Costello—They recalled Gehman’s explanation of this: “It was extremely difficult, some years ago, for any of the Toots Shor mob not to meet Frank Costello, for that gentleman was in Shor’s nearly every day when he was not in jail, whether Toots wanted him in there or not. I myself one day was bought a drink by Frank Costello, who asked me how the writin’ business was.”

Sinatra’s carrying two million dollars to Luciano—They put forth Frank’s own denial of Mortimer’s charge: “Picture me, skinny Frankie, lifting two million dollars in small bills! For the record, two million in dollar bills weighs five thousand pounds. Even if the bills were twenties, the bag still would have required a longshoreman to lift it. Actually I stepped off the plane in Havana with a small suitcase in which I carried my sketching materials, oils and personal jewelry.” (Luciano, now dead, was actually hurt, not helped, by Frank’s visit and commented, “I had a nice deal going for me. I owned a piece of the dice table action. I played golf in the afternoon and went cabareting at night.” Then, as Leonard Lyons points out, the Sinatra publicity, following that one-day visit, resulted in U.S. pressure on Cuba and blasted the vice king back to his native Italy for good.)

5) Sinatra as first a pawn of and then a front for the Mafia—They submitted the opinion of Capt. James Hamilton, of the Los Angeles Police Department’s Intelligence Division, that “Nobody has ever become a Mafiosa because of wealth, position or power. You have to be born into the fraternity, or at least marry into it.”

Finally, although they admitted that Frank has at one time or another had altercations (occasionally violent) with Lee Mortimer (perhaps that’s why Lee kept crying “gangster”) and with assorted publicity men, parking lot attendants, newspapermen, hotel clerks, gate crashers, racists and the like, they also emphasized that there’s a big difference between being a hot-headed guy who fights at the drop of a slur and being a mobster.

His friend Bing Crosby once said of Frank: “I think that he’s always nurtured a secret desire to be a ‘hood.’ But, of course, he’s got too much class, too much sense, to go the route—so he gets his kicks out of barking at newsmen and so forth,”

And there were others—close friends as well as disinterested observers—who defended Frank against the new accusations that were leveled against him.

Louis Sobol, by implication asking why Frank had been picked out by the Nevada gaming commission as its scapegoat, wrote: “What the local gambling fraternity can’t understand is all this fuss about Sam Giancana’s stay at Cal-Neva Lodge when it is no secret he has financial interests in several casinos in Nevada and has occasionally lodged in Vegas hotels, too.”

Both Las Vegas newspapers printed editorials supporting Frank and attacking the commission’s attitude.

Sammy Davis, Jr., speaking at a press conference in Melbourne, Australia, where he was performing, called the charges “hog-wash.” Sammy said, “I admit Frank is no Little Lord Fauntleroy, but these charges are ridiculous.”

Attorney Greg Bautzer stated, “I don’t think it should be possible that an individual can lose a property right by virtue of having a friend. I can even have a convicted individual as a friend if I desire and there’s no law that says I cannot.”

Son defends father

But it was Sinatra’s son, Frank, Jr., whom newspapermen called upon to defend his dad—and to explain why his father had skipped the New York opening. With the applause of the crowd still ringing in his ears—he had silenced their whispering all the time he’d been out there on the stage and he had shown them he could really belt out a song—Sinatra’s boy braved the questioning of a swarm of reporters. He didn’t fence or duck, but answered their questions directly.

Why hadn’t his father been present?

“I spoke to Dad on the phone, and he was coughing badly. He was very tired. He’d been working all afternoon on his record business. He thought he’d stay home until he felt better.”

Did his father fail to appear because of the Nevada situation?

For a moment the boy’s face flushed, then he controlled himself and said, “I’ve discussed it with my father and he said when he’s ready he’ll make a statement.”

Two nights later, Sinatra did show up and he did make a statement. But first he sat quietly at a small table, beautiful Jill St. John by his side, and listened to his son. And Frank, Jr., seeing his father’s face at ringside, sang his heart out.

When the show was over, Sinatra pounded his hands together in applause. For a moment he looked almost startled, as if he might be clapping all alone, but as he glanced quickly around he saw that everyone in the room was applauding, too, and he grinned as he saw that their eyes were not on him, but on his boy.

Photographers pressed through the cheering crowd, but he waved them away. Later, when he posed with his son in the lobby, he explained to reporters why he’d turned down the photographers inside: “I didn’t want anything distracting my son.”

And now, as he beamed and hugged his son to his side, his voice was filled with pride. “He sounds just like his old man,” he said. Then he shook his head as if that’s not what he wanted to say at all. “As a matter of fact,” he corrected himself, “the kid sings better than I did at that age. He’s got a good chance, a hell of a good chance. I think he’s more advanced than I am now—way ahead of me because he’s a studied musician, which I’m not. I think it’s a matter now of serving an apprenticeship.”

But now the reporters started firing questions fast and furious, but the elder Sinatra didn’t flinch and the younger Sinatra didn’t move from his father’s side.

What about the gaming board charges?

“I don’t know what they’re talking about. There’s nothing I can say. I won’t know anything until I get back to Los Angeles and talk to my lawyers.”

Would he give up his Nevada holdings?

“We’ll fight back!” (Later, columnist Earl Wilson asserted that Sinatra told a friend that he did not threaten the Nevada gaming board; he merely said to one member, “You’re a bunch of bums.”)

This is where herd come in

At that moment a pretty, middle-aged woman walked up to father and son. Ignoring Frank Sinatra, Sr., she held out a menu, giggled, and then asked if Frank, Jr., would autograph it for her—and if he’d add the words, “With Love.”

Sinatra grinned—this is where he’d come in twenty years before—and slipped away into the night, with Jill on his arm.

Two days later and the Nevada cauldron was bubbling faster than ever. Sam Giancana’s whereabouts were unknown to the press; Phyllis McGuire was reportedly resting in her sister Christine’s home in Ft. Lauderdale, Florida, suffering from “nervous exhaustion;” and Sinatra’s lawyers on the Coast were studying the charges against their client and readying their reply to the Nevada commission.

Where was Frank?

Well, he showed up at the General Assembly Hall of the United Nations in New York City, where he emceed a show for three thousand members of the UN staff.

Was he retiring, subdued, chagrined?

Well, after being introduced by Secretary General U Thant as “the great lifter of spirits” (a diplomatic touch—friendly, but not committed), which brought an appreciative laugh from the audience and a mock look of disdain from Sinatra, Frank asked the rhetorical question, “Do you mind if I smoke?”—lighting a cigarette at the same time, and then he set the tone of the evening by saying, “It’s essential to relax—with the stress and the hot spots around the world. Vietnam. Congo. Lake Tahoe.”

Then, as the audience was still laughing, he stepped forward a bit and said in a stage whisper, “Anybody want to buy a casino? I didn’t want it anyway. I’ve got four hundred dollars in six banks.”

Anyway, Frank Sinatra was already fighting back—with good humor.

But it turned out that he really didn’t want it. He was going to pull out completely, he decided. As we went to press, his Las Vegas attorney, Harry Claiborne, revealed Sinatra’s intention to “divest myself completely of any involvement with the gaming industry in Nevada.”

And Frank Sinatra, Jr.—there wasn’t any reason for him to say anything further, because he’d said it all already—before. “I’m proud of my name. I’m proud of my father . . . What I’ve learned from him is to abhor prejudice, to respect the other fellow, to be honest and uncompromising with principle. When it comes to principle, my father never wavers.”

There was no reason for Frank Sinatra’s son to say anything further—so he closed his eyes, leaned back and just kept singing.

THE END

—BY TONY ANTHONY

Frank appears in “Come Blow Your Horn,” Paramount, and “4 For Texas,” Warners.

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE DECEMBER 1963