Ooh, What Polly Said! Ooh, What Phil Answered!

The rumor was going around that Sergeant Bilko had come up with a real dilly of a scheme for the platoon welfare fund—which, of course, is just another way of saying that the proceeds land in Bilko’s pockets. It wasn’t too clear what this scheme was all about, except that somehow Polly Bergen was involved. Now this made sense because Polly and Bilko’s friend Phil Silvers are old buddies from way back. Except another thing, though, which was that Polly just didn’t seem the type to get involved in a Bilkoan enterprise.

So we hopped over to Polly’s and started to explain the scheme, which was very difficult since it involved a parakeet, a calliope and a cigar box. Polly listened very intently, pot changing from the real serious expression that had come across her face as soon as the name of Bilko had come into the conversation; not blinking or even smiling when the explanation of the scheme got tangled up in the lonely stretch of highway that leads from Roseville, Kansas, to Fort Baxter—Bilko’s estate, you know.

She merely took her glasses off and started talking.

“Did you know that at the age of eleven Phil Silvers sang in a movie house in Brooklyn whenever the projector broke down?” she said. “The house lights would come up and Phil would have to jump up on the stage. take his glasses off, spread his arms wide and sing something soothing. On the face of it, there wouldn’t seem to be much future in something like that, not only because it didn’t pay much, but also because it depended on the film breaking or a projector popping a gasket. But even then, at the age of eleven, the Bilko technique was well developed. Yes, sir, those lights came on quite often in that Brooklyn movie house. I understand that the projectionist retired at an early age.

Polly: “Wait’ll you hear about the time I lent Phil my platinum wedding ring to marry Evelyn, and . . .”

“Excuse me,” she said. She rose and did a dainty pirouette. The NBC rehearsal hail, where Polly was working on her Saturday night “The Polly Bergen Show,” was just the right place for this sudden little touch of show business. She was dressed in tights and had been sitting, in the traditional behind-the-scenes show-business way, on a chair turned around. Finishing the pirouette, she came to a sudden halt, flung her arms out and started to sing—except that she was just mouthing it. Then, just as suddenly as she had started, she stopped.

“I feel so good! ” said the ex-Pepsi-Cola Girl. “Now that may seem odd since this is the Thursday before the show and we have been working awfully hard and there’s nothing but more work ahead for the next two days. But I feel good! Maybe it’s because you mentioned Phil. He always peps me up. Gee, I’ll never forget the recent sitting. Gee, I feel good!”

And the blue-eyed, brown-haired, pert Polly went into a soft-shoe routine that was anything but routine. She strutted a little, shuffled along, bucked-and-winged, did some of that stroll that is the big craze these days, threw in a quick little mambo step, went back to the soft shoe and wound it up in a statuesque and thoroughly convincing tango (she still claims she can’t dance) with an imaginary partner throwing her out into the final turn so that she ended against a pillar, limp yet oh so glamorous. Yes, even in those working clothes, glamorous!

“Bravo, Helen!” called a stagehand from the other side of the room. “Bravissimo! Helen want a cracker?”

Polly wrinkled her nose at him in mock disdain and sat down in the chair, still turned around, with her arms crossed over the back. She smiled and said, “Ever since I played Helen Morgan on TV, I’ve been kidded when I do something the least bit dramatic or torchy. The joke about the cracker comes from the fact that Helen Morgan, back before she became a star, once worked at NBC—only this was the National Biscuit Company and not the broadcasting company. Of course, what is supposed to make the joke funny is that my name is Polly and the usual line is ‘Polly wanna cracker?’ Well, I suppose it isn’t really funny, but that’s life, around here at least.”

She shook her head and gave a rueful laugh. It was just a month or so before that Polly had stood up on a stage in New York and received a coveted Emmy for her moving portrayal of the famous torch singer on “Playhouse 90.” She had shed a few tears in accepting the award, genuinely surprised that she had been judged top TV actress of the year. And here, backstage, it was treated irreverently—but it was an irreverence that carried respect and affection.

“Well, we were talking about Phil. He was a master of ceremonies for the Emmys, you know and it really was wonderful to hug him when I got to the stage! Helped me stand up. Of course, he and the writers of ‘The Phil Silvers Show’ also received Emmys, but to them it was nothing new. That show of Phil’s just keeps on winning.

Phil: “Ha—she tried to sing a hillbilly number at the wedding, but she’ll bust Sgt. Bilko in clay only!”

“But we were in that Brooklyn movie house, seems to me,” Polly went on. “Say, let me tell you a story about Mr. Bilko’s buddy Phil Silvers. When Phil and Evelyn got married, in the fail of 1956 (the same year Freddie and I were married), it was a sudden decision. Not that they hadn’t planned to get married. They had known each other for a year—my husband introduced them. They were definitely going to get married, but no date had been set. Phil was busy with ‘You’ll Never Get Rich’ and Evelyn (she was Evelyn Patrick) was doing commercials on ‘The $64,000 Question.’ But they decided there was no sense in waiting any longer and, since it was a sudden decision, they didn’t have a ring. So I loaned them a platinum wedding band.

“Well, the four of us—Freddie, Phil, Evelyn and I—had breakfast in the Fields apartment. Freddie is Freddie Fields, you know. Then we drove up to Connecticut for the ceremony, after which we came back to the Fields apartment for a private little wedding dinner.

“Well, there they are, happily married. and I do mean happily. You know they have a child now? Tracey, her name is. Well, naturally Phil was going to buy Evelyn a wedding band and I forgot all about my band. One day, about a week after the wedding, I received a phone call. It was a man, and I felt that I had heard the voice somewhere, but I couldn’t be sure, so I simply listened to this story.

“ ‘I am Sam Shanks,’ he said. At least I think that’s the name he gave. ‘I direct an investment establishment on the corner of Eighth Avenue and Twenty-fifth Street.’ Well, I immediately started thinking that it sounded awfully strange. It seemed to me that Eighth Avenue and Twenty-fifth Street was an odd location for an investment establishment. Immediately it came to me. He was a pawnbroker! And what in the world did he want from me?

“But I let him continue. ‘We have received a request for an appraisal of a wedding band—platinum, I do believe it is,’ he went on. ‘A chap dressed in a uniform of some sort has called it to our attention. We have been apprised of the fact that this band was yours. Madam, is it yours now or does this chap in uniform rightfully claim it? If the former, we will, of course, notify the authorities. If the latter, would you mind giving us an estimate of its worth?’

“Well, to tell you the truth—say, that’s the name of a TV program I’ve heard of, isn’t it?” Polly made a little girl smile and tilted her head slightly in a put-on pleased-with-herself attitude. On another network (CBS, of course) Polly is a panel member of “To tell the Truth.”

“Well, as I was saying,” she continued, “I was genuinely disturbed. I know that Sergeant Ernie Bilko might in some clever way that would make everything legal in the end do such a thing, but certainly not Phil Silvers. I hung up on Sam Shanks or whatever his name was and started to dial Freddie. But then I decided not to. I walked around the apartment for a minute or two and then went to the phone again to call Freddie. Then the doorbell rang. I went to the door and opened it. It was Maurice Gosfield, who plays Private Doberman in ‘You’ll Never Get Rich.’

“ ‘How do you do, madam,’ he said with a suave smile that Private Doberman never has. ‘I do believe that you are the rightful winner of a grand prize. Madam, with the compliments of the entire establishment of Shanks Limited, may I bestow upon you the Grand Award for Duty Beyond the Call of Bravery, 1956.’

“And he handed me my platinum band. And turned grandly on his heel and left.”

Polly shook her head and slipped her glasses on. She frowned. It was the sort of frown that a person gives after recalling something from the past that I really wasn’t so bad, after all.

“I was so flabbergasted,” Polly said. ”And I tried to be mad, too, but it didn’t come. No, I was so flabbergasted and tickled and—oh, I just don’t know how to describe it. It was so typical of Phil and his gang from the platoon!”

She laughed. “That darned platoon of his! Remember when the Emmy ceremony started? Phil was the first one to appear. He came marching up in a really grand uniform—seemed to me it was a cross between the French Foreign Legion and something out of the Roxy Theater—and the band played some marching music that had been jazzed up a bit. Behind him in their usual unsmart military dress came the platoon, Doberman up near the front. Phil gave a couple of Bilko orders and then moved on off the stage. Phil said, ‘There go the men who will put my child through college!’ Tracey has a long way to go before college days, but the way that platoon carries on, I think he was right.”

But there was this rumor about a Bilko scheme to attend to and so far there was absolutely no clarification on it. Furthermore, Polly had mentioned a sitting of some sort, and that sounded intriguing. Was it for a portrait? And who was the artist? Dali, perhaps?

But clarification was not forthcoming, at least not at this time. Polly rested her chin on her crossed arms and went on to another subject.

“Did you know that Phil was discovered at Coney Island by the famous Gus Edwards?” she asked. “That’s right. Phil was singing on the beach at Coney Island, doing some imitations of the stars who played the famous Palace Theater. The Palace, there was a place in the good old days!” Her lips parted in delight as she obviously was seeing visions of Eddie Cantor, Georgie Jessel, Al Jolson and the others who thrilled so many people at the Palace. “Not that I played the Palace in the old days, you understand,” Polly said hastily. “After all, that was just a little before my time.” (Since Polly will be just twenty-eight on July 14, she obviously isn’t of the same school as Cantor, Jessel and the others.)

“Well, as I was saying,” she went on, “Phil was singing away on the beach one day. all that work between broken reels in the movie house seemed to have done a fine job of developing his voice. He was just fourteen and there he was, singing away on the beach with some of the boys, and a man tossed him a card. On it was written ‘Come see me, young fellow,’ and the name printed on the card was Gus Edwards. Yes, the famous Gus Edwards, whose ‘School Days Revue’ was the jumping-off place for many stars. And in just two weeks Phil was singing at the Palace. Two weeks, mind you! Imagine! One day he was singing in a Brooklyn movie house as a substitute for a split film and just two weeks later he had moved across into Manhattan to the famous Palace. Just across the Brooklyn Bridge, but what a trip!”

Polly shook her head again in that rather pensive way that women have in looking back at the past—even someone else’s past. There was no doubt that she could recall it.

“Well, the next step was obvious,” she said. “He would simply wow them at the Palace and grow up to be a singing star par excellence. Why not? Well, because his voice soon cracked. In the process, it became something less than beguiling, and he was no longer a singer. Not even that Brooklyn movie house would let him back. This was really a tough break. But it didn’t stop this youngster. Like Bilko, the young Silvers was a resourceful sort. So, the next step was simply . . .”

It probably wasn’t the polite thing to do, but it seemed as though the only way to track down that rumor about the parakeet, the calliope and the cigar box was to find Phil Silvers himself. There was something in the background that sounded like “Joe and Flo” as we tiptoed away. (We really didn’t feel too guilty, since Polly had to rest and then go on rehearsing and it wasn’t fair to keep taking up her time, was it? That’s how it worked out, using a little rationalization.)

A half hour later, off on the other side of town in another hail, this one a CBS spot, Phil Silvers put out his hand to be shaken, nodded and said, “It was like this. Joe Morris and Flo Campbell had a comedy routine. When my voice cracked . . . oh my, how it did crack! Like a bamboo reed split with a fine knife, it cracked. So I became a brat in Joe and Flo’s sketches. My, but was I a brat! Loved it, loved it.”

Obviously Polly had not been deceived into thinking that her listener was still over at NBC, listening. Pert Polly had deduced that the next person on the itinerary was Phil (how the deuce did she deduce it, anyway?) and had called Phil to fill him in.

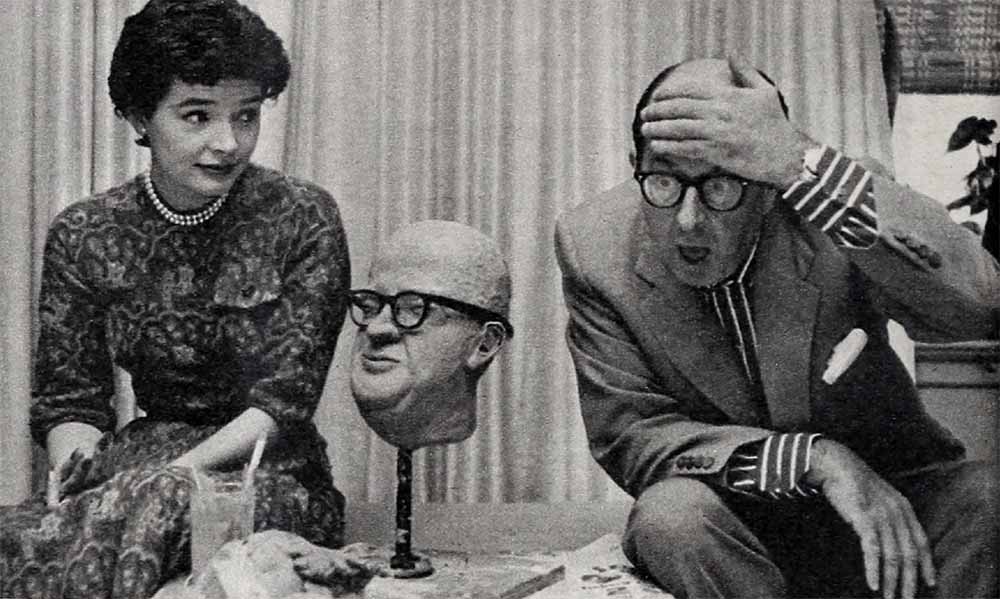

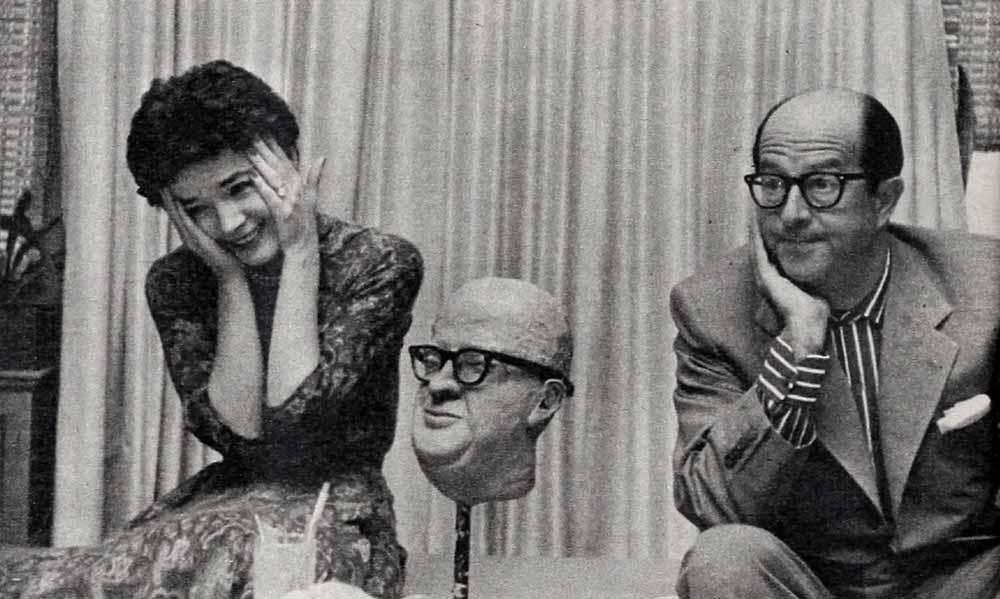

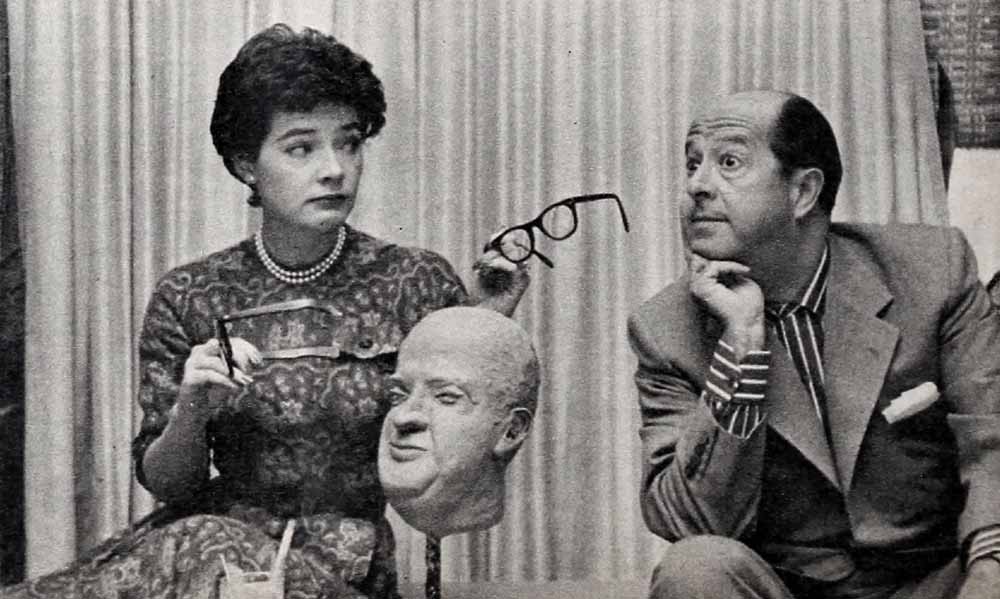

“Now I understand that you are interested in Polly the sculptor,” Phil said.

Since this was the first time that “sculptor” or anything like it had come into the conversation—either conversation—it was hard to agree. Yet it was also hard not to agree, not only because to do so would be impolite, but also because there was a very definite feeling that all this would make sense.

“Well, it was like this.” Phil said. “Polly sculpts. Is there such a word? Sculpt? To sculpt? Let me see.” He put his hand to his chin and stroked it. It was remarkable how much his deep-in-thought expression looked like Polly’s. Not that they resemble each other, of course, except for the inevitable glasses. Phil was wearing his glasses now and Polly had not been wearing hers much of the time. Yet despite this, and the fact that they certainly do not look alike, their expressions while in serious thought (or at least something like serious) were certainly remarkably alike.

“Sculpt? Ah, well, what’s the difference? She’s pretty good at it. Cooks, too. Say, did she tell you about the time she did my bust? Boy, that was a riot! I sat and sat and sat—never thought I could get off the chair. Every time I tried, she said, ‘Give me a soulful look from those blue eyes,’ and down I’d go again. I was like clay in her hands. Say, that’s a good one! Have to tell that to Bilko’s writers, if I ever meet them. Amazing. Amazing! How a show like this can be written and the star never sees the writers. Amazing!

“Boy, was I ever clay in her hands. She shaped me and looked me over and shaped some more and looked some more and I would get up and then would come those soulful blue eyes and down I’d go, clay again. Funny thing, she was working, but I was wearing the glasses. I ask you! When she was through she put glasses on the bust and I guess it looked like me. Only don’t tell Polly I said ‘I guess.’ Anyhow, she can cook. And another thing, I was only kidding about writers. We’re always kidding about the writers. You know, here a guy stands up here day after day saying a line forty-eight times over until the director and the sound technicians and the cameraman and who knows who else say it’s okay. And do you know what? It took the writer forty-eight seconds to borrow that line from some place or other, and me it takes forty times to get a simple, two-sentence line down on that film. Sometimes I feel like I’m in that Brooklyn movie again, waiting for the film to break. Did you know that I got my start singing in a Brooklyn movie? Oh? —you know?”

Phil slapped his khaki-clad leg and chuckled. “Well, if you’ve been to see Polly I guess you have the story. Maybe not the exact precise story, because she’s inclined to elaborate a little when it comes to me. Probably even told you the one about the wedding band.” Phil looked up sharply, putting out all that stern Bilko militarism to ferret out the truth. When he saw that the truth was out, he relaxed and nodded.

“Thought so,” he said. “Well, never mind. From me you will get facts about Polly. Facts!” He slapped his leg again as he repeated this. “You know, our girl Polly leads her family life with as much pep as she conducts her career. Her husband, Fred Fields, who’s vice president of a big talent agency, is an old friend of mine, and so the four of us have some real balls when we get together. Even our bridge games are full of wise-cracking. And eleven-year-old Kathy Fields, Polly’s stepdaughter, is her biggest fan—next to Freddie and Evelyn and me, natch!

“You know, Polly was married once before—to Jerome Courtland, an actor, but it didn’t work out. Polly was too young.

“The interesting thing about her is that her musical upbringing was a genuine family thing. Her father, whose name was Bill Burgin (maybe you saw him on her show a few times), was a hillbilly singer and Polly learned all the songs her father loved. Why do you know, she even started to sing ‘When My Mammy Cried to the Hound Dog That Little Ole Hound Dog Cried Right Back to Her’ at my wedding! Yes—but here here! Facts! The facts, man, are that that isn’t true at all.

“But it could have been. That’s an interesting thing about people in show business. You may hear a lot of stories about how cold or tough or this or that they are, but I can tell you they aren’t much different off the stage than they are on it. It’s just plain impossible to be one way in front of the camera or the footlights and a completely different way behind the scenes. It wouldn’t be long before it would show up and then what chance does the entertainer have to hold his audience?

“So what I’m getting at is that when you watch a Polly Bergen joshing with Bud Collyer or Henry Morgan on a TV panel show, just kidding back and forth, that’s the same Polly who could have sung a classic about the hound dog. And she could have made it up, right on the spot, too.”

There was a lot of activity suddenly blowing up. As Polly’s rehearsal hail had been at the start, this CBS spot was a well-organized center of disorganization. Sets were suddenly put into motion, cameras came careening around on one wheel, men shouted odd phrases and then, just as suddenly as it had started up, it was quiet, with Phil Silvers standing in the middle of it. His corporal buddies were all ears as Sergeant Bilko was obviously preparing to bestow upon an unsuspecting world—or a platoon, at least—the latest fruits of his genius.

“Rocco, tell you what,” he said, elapping his hand on the shoulder of Corporal Barbella (real name: Harvey Lembeck). “You get down to the colonel’s house and . . .” and then Phil (TV name: Ernest Bilko) leaned over and whispered in the corporal’s ear, upon which the latter’s eyes lit up in an appreciative salute. “And Corporal Henshaw (real name: Allan Melvin), you slip over to the supply room, through the back window, of course, and pick up . . and he leaned over to whisper in the second corporal’s ear. This one’s eyes lit up, too, although not in salute. This one is more like a fellow-conniver than a devoted follower, such as Rocco, and his eyes had a distinct and eager leer. Both corporals nodded and dashed off, a Napoleonic voice stated “Cut” and disorganization once again.

Phil came back. “Come into my boudoir,” he said, and led the way. In the dressing room he sat down and placed a record on a turntable and leaned back to listen. It was Polly, singing “The Party’s Over,” the theme of her TV show.

“Isn’t that lovely?” he said with a sigh. “Really got a nice way with a song, has this young lady. Yes sir, Columbia Records did a good thing with that song, waxing it with Polly. And to listen to that, you’d never think she can cook, too. Sculpt? Well, maybe. But cook! The greatest! Now there’s this item right smack out of Dixie, with beans, pickles and good old corn bread.

“And furthermore, she has a passion for party games and she shoots pool. I ask you, how she shoots pool!” Phil clapped his hands to his forehead and then looked up at the ceiling with that speechless Bilko request for divine assistance. “Why, I wouldn’t let that girl into the recreation hail with a ten-foot cue stick! She would take the platoon apart. Say, there’s an idea for a Bilko story. Must make a note of that.”

Phil looked around for a pencil.

The parakeet, the calliope and the cigar box never did get into the boudoir. It didn’t make much difference, though. A day with P and P at NBC and CBS went PDQ and it ended with the last charming notes of the song—yes, the party was over and a delightful time was had.

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE JULY 1958