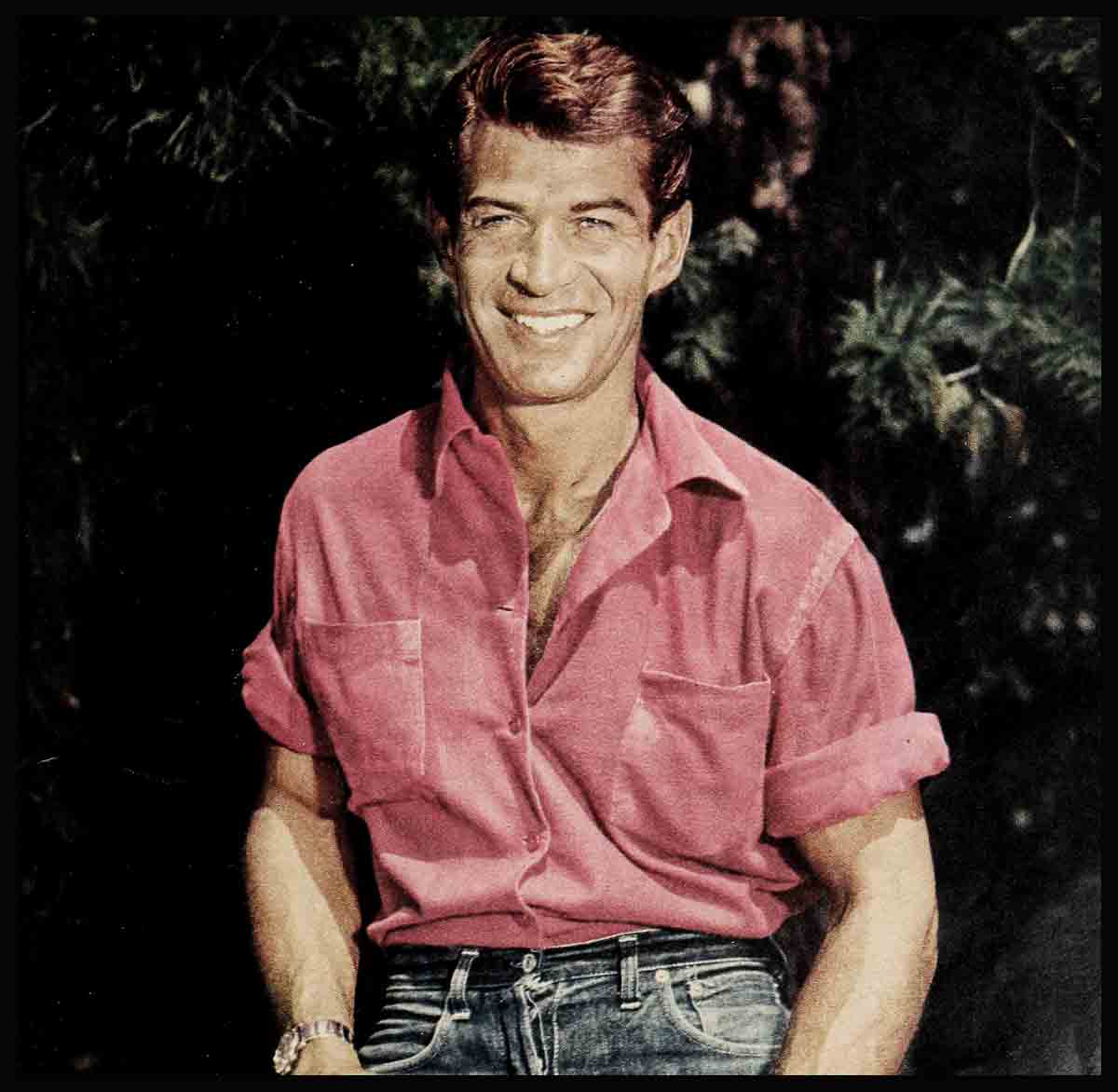

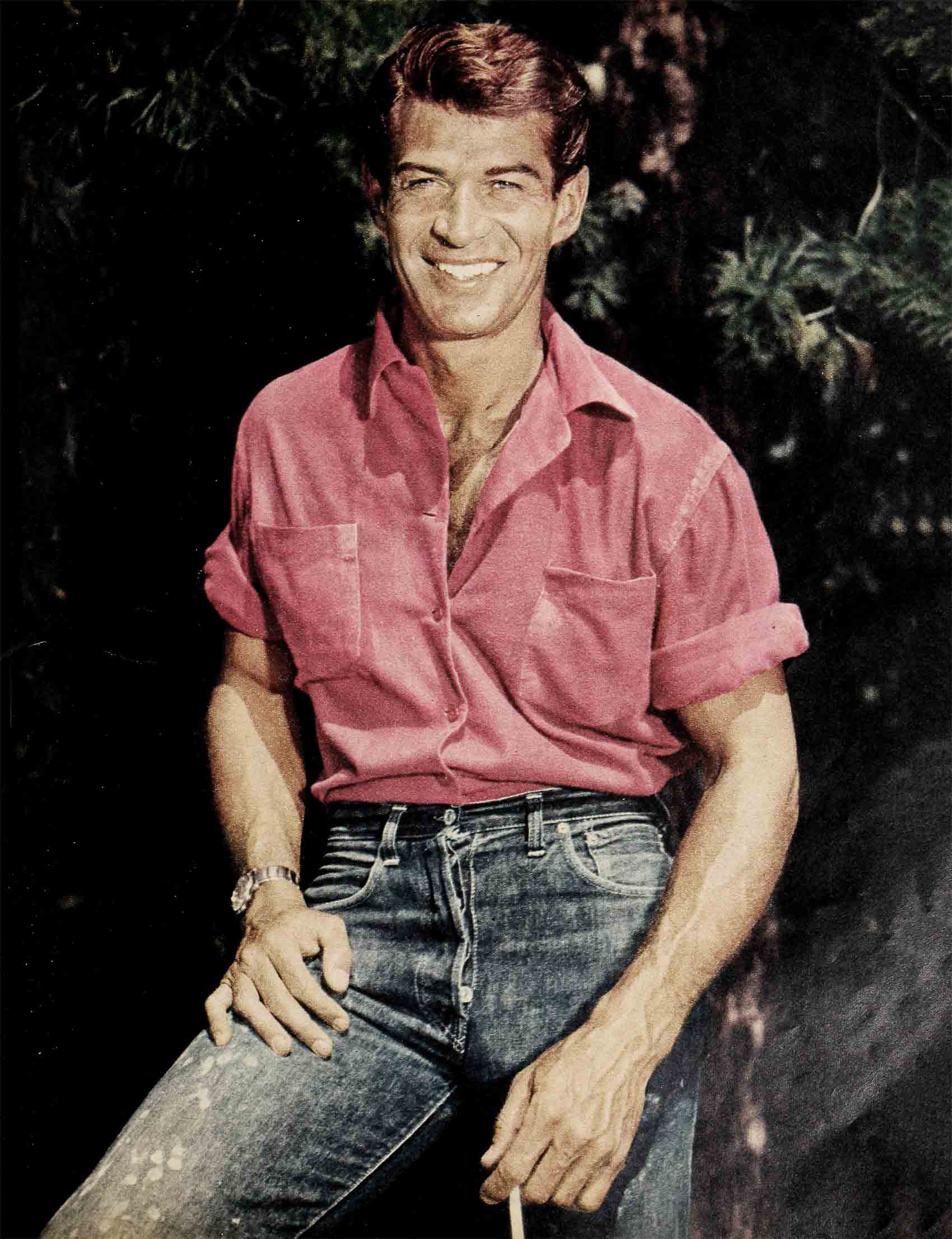

Wanted: One Good-lookin’ Country Girl—George Nader

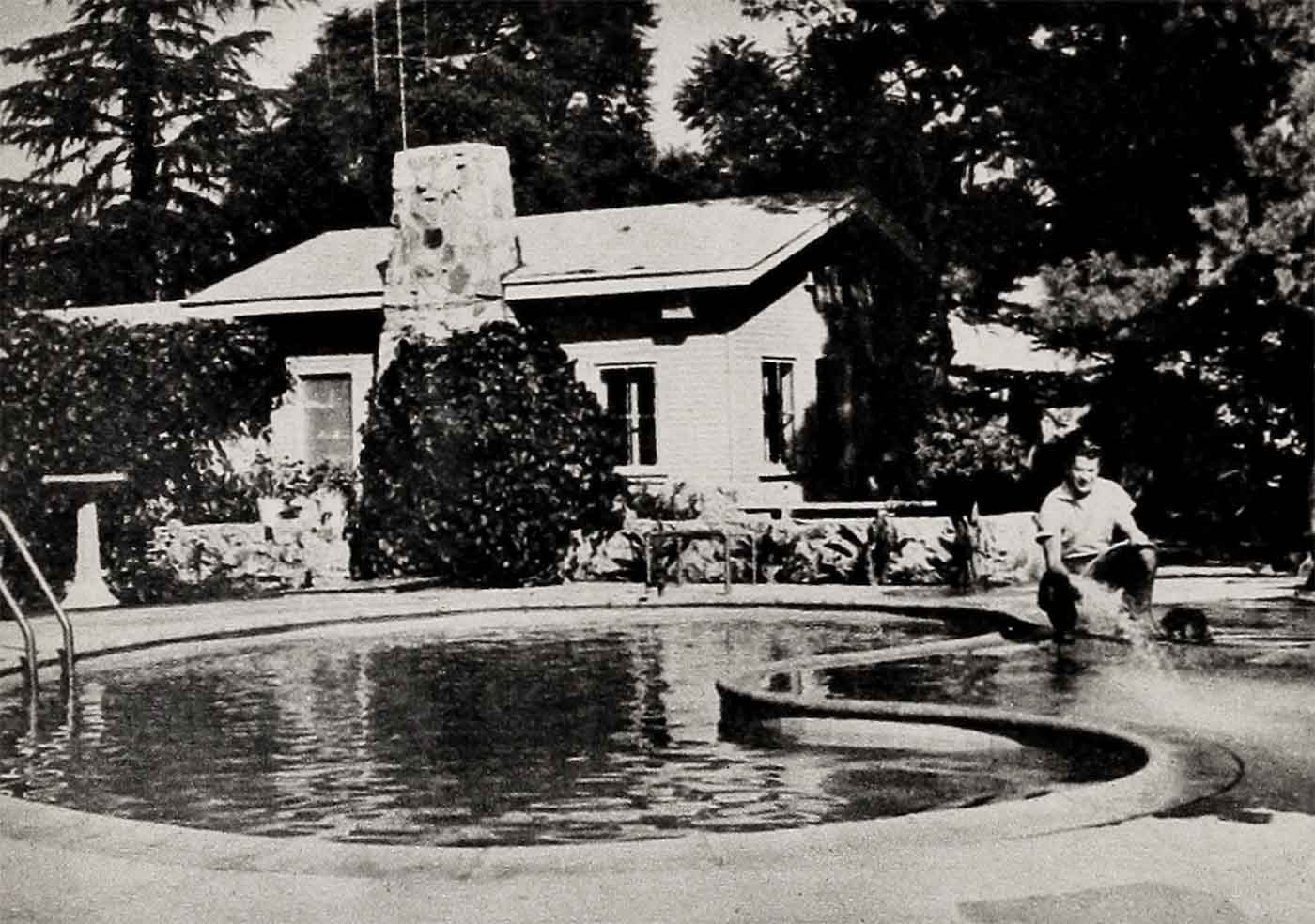

Rubbing his eyes, yawning, stretching, blinking in the early morning sun, out of the old white house came a young giant. He stood well over 6’ 1, clad in ancient jeans and comfortable t-shirt. In one hand he carried a hoe, in the other a spade. The hands holding them were well-calloused.

With a practiced eye he surveyed his domain. Around him trees stood tall, flowers turned their petals to the sun, weeds—weeds were non-existent. George Nader lifted the spade and the hoe to his shoulders and sighed. It was all his; he had done it all. And here was another day, warm with a sun that would eventually peel the shirt off his back, perfect for gardening, for finishing the path that led ’round the house, for repairing the hose—for spending the twilight at the piano without a neighbor in sight to be disturbed. How tremendous to have a couple of weeks ahead all to himself. How marvelous not to have to struggle into a shirt and tie and go somewhere. He thought he’d never in his life been as happy as he was today, yesterday, tomorrow.

Only—what was wrong today? He sighed, he felt restless and uneasy, he wanted—something. The greenery gave him little pleasure. Something—and then he remembered. Suddenly the simple, uncomplicated, outdoorsy young farmer was galvanized into action. Of course he knew what he wanted—he wanted to be at the studio. What on earth was he doing perched on a hill miles away from Hollywood? Why wasn’t he down there, acting up a storm? How had he avoided being bored to death here, without the hum of a movie lot, the smell of make-up and machinery, the thrill of knowing that his big scene was to start in a minute, that he, George Nader, would be before a camera, taking direction, moving into position—acting! What madness was this?

He dropped the spade and the hoe. Twenty minutes later, in the doorway where the young farmer and amiable putterer had stood, there appeared a movie star. Then he was driving his car down the winding roads back to civilization, crowds, people, the studio, the work he loved—the other life that gratified him, supported him, and was just as necessary to him as the garden he made.

Lonesome

But the closer he got to the city, the more nervous he became. Upon the hill he was safe and happy. Down there—the only trouble was, he got hurt sometimes.

For instance—there was the little matter of being lonely. A man may like his house and his garden and the world in general—but the nicer things are, the more he’d like someone to share them with. He often thought about his girl. He knew pretty much what she’d be like.

She’d have a sense of humor like his, consisting partly of a wry enjoyment of the confounded way things can go wrong, and partly of a quiet happy chuckle at something that tickles her fancy. If she wanted to play practical jokes or dance barefoot on tables, she’d have to find herself another partner; that wasn’t for George. Secondly, she’d be bright; thirdly she’d be neat and sweet to look at, not necessarily beautiful and definitely not gaudy—and lastly, she’d have a deep, abiding love for one George Nader and a desire to settle down and raise a family.

But in the world of a movie star, the trouble was—finding her. Once he thought he had. She was Dani Crayne, and she liked him, too. So what happened?

Dani got lost

Never were there two young people who got more lost under an avalanche of publicity. It started out as fun—not exactly friendship, but certainly not great love—just a nice, healthy, dating relationship. By the time they had been out three times the columnists were complaining that they didn’t know what Nader was stalling about—why didn’t they get married? He and Dani found out more about each other in print than in person—including that they were going steady, engaged, broken-up, seeing others on the sly, and every now and then, that they were secretly married. By the time it was all over, a bewildered George was saying, “Everyone keeps asking me if it was love. How should I know? We never got a chance to find out.”

Now, as his car hummed powerfully along, he suddenly realized he wasn’t even looking forward to love. A pretty sad thing to think, considering he was thirty-five years. old, earning a good living, and working in a town that probably had more cute girls than the rest of the world put together. Never mind, he told himself. Eventually, I’ll find her—here, somewhere else—who knows? And when I do, and I fall in love with her, and people say to me, “Well, George?” I’ll have an answer ready in advance to keep the hounds off the trail. Something like—“Oh, it’s just publicity. I need it badly.” He grinned to himself. At the door of the church, with the minister waiting, he’d tell the crowd, “Oh, it’s just publicity.” Ha!

He chuckled quietly to himself the rest of the way to town, parked the car and looked around for a place to grab a bite. Halfway down the block he spotted a guy he hadn’t seen in maybe three years, and waved. The guy paused, peered, then grinned from ear to ear and started leaping fire hydrants and dodging trucks in his mad dash to George, who stood petrified watching the advance. It was as bad as he feared. A wallop of tremendous power hit him on the back and a voice screamed in his ear, “Hey, George—hear you’re a great big movie star now!”

“Now, where the blazes,” George muttered to himself, “is the conversation supposed to go after that?” Aloud he said, “Uh, no. Well, yes. I mean—I got a date, I’m late,” and dashed off, leaving his friend to tell the old gang, no doubt, that Nader had gone Hollywood.

Friendship?

Well, it wasn’t always like that, he reflected bitterly. For instance, George had one set of friends, a married couple, to whom he felt free to fly in times of stress and strain. There was always a racket going on in their house, a bunch of pals sitting around chewing the rag, a good loud babble from friendly people, each trying to sneak a word into the conversation and accepting cheerfully the impossibility, of making themselves’ heard. Happily, George would head for this refuge, to be one of the gang. It worked great until one day he opened his mouth to make one of those vain attempts to be heard, and found that he could be. In fact, the minute he parted his lips, a dead silence fell on the room. With one accord, in all corners, conversation ceased and ears were lent to the words of Mr. Nader, the movie star. The sudden silence positively deafened him; in the middle of a sentence he sat with his mouth open, haying forgotten what he planned to say. Finally he came out of it and went on. Five minutes later he tried again. The same thing happened. It wasn’t a gag. “George,” said his hostess encouragingly, “do go on.” “Yes,” voices chimed in, “what is it, George? Don’t stop.” George recovered his wits. “What the blazes is going on here?” he demanded. “Listen, I don’t mind if you want to be polite, but what is this—I’m getting idolized? Here?” His accusing gaze swept the room. “Look, I knew you all when we used to borrow money from each other—when I—” But no one interrupted, no one said a word, sitting there fascinated. “Oh, what’s the use,” muttered George, and sat there, lonesomer than ever.

A fair exchange

Still remembering, George turned into a luncheonette and sat down at the counter. Quit this, he told himself sharply. The way you’re going on there’ll be nothing left to do but crawl into a hole and pull it in after you. Now figure—how many friends have you actually, honestly lost in this business? All? Good God, no. Half? Nowhere near. A third? A quarter? Well—maybe four or five. And how many new ones have you made? He counted. Two, three good ones, guys he could talk shop with and really learn something. Altogether, a pretty fair exchange.

His appetite restored, he reached for a menu and discovered that someone else had got it first, and was offering it back to him, with a pencil. “Autograph, Mr. Nader?” George roared with laughter.

“Did I say something?” the kid asked.

“No, not a thing,” George chortled, signing cheerfully. “I was just remembering the last time I got asked. . . .”

It had happened a few weeks before when he was in the east.

George had been lying on his back, letting the waves tickle his ears. He was floating, not only on the cool Atlantic ocean, but in his mind as well. It was a swell day. Soaking up the sun on the beach with an old friend, a hot dog for lunch, no place to go, nothing to do. He opened his eyes, blinked at the sun, and peered towards shore. There, a comfortable distance away, was a scattering of people who didn’t know who he was and didn’t care. No one had stared at him, whispered about him, asked him to autograph an album—who’d have an album at the beach? George sighed, blissfully content. Then, something tapped him on the shoulder.

May I have your autograph?

It was so unexpected that he jumped. His feet went down and his head went after. Gasping and sputtering, he came up for air, shook the water out of his eyes and stared. There, treading water like mad, was a little girl, ‘way out of her depths. In her eyes was a rapt expression, in her hand was clenched a soggy popsickle wrapper. She gazed at him adoringly. “Please, Mr. Nader,’ she panted, her short legs flailing the water, “will you autograph this?”

Now, chewing his lunch, he said to himself that that was the kind of thing that made it all worth while. Sure, he missed his privacy but, after all, how many men—even great men of history, say—had had their fans—or whatever they called them—risk drowning just for a signature? What, for that matter, had George Nader done to deserve such un-dampened ardor? Nothing. It was the business that did it. So don’t knock it.

Nader versus Nader

All in all, it was a good world. This afternoon he would astonish the still-photo department by showing up of his own free will and suggesting that they take those portrait shots they’d been yapping about for months. Then he’d go over and have a chat with the director who had that new action picture coming up and wanted to talk to him. Maybe he’d drop over to one of the shooting stages and watch a while. And this evening—well, tonight would be all right. He’d pick up Gia Scalla—what a doll that kid was—and he’d take her to the premiére. Maybe afterwards they’d go over to the Palladium and close it, dancing up a storm, the way they had a couple of weeks ago.

And when they got to the preme, he could see it all in his mind’s eye. At the door there’d be a man with a notebook, wanting to talk to him. “Hey, George,” he’d say, “I hear it’s quite a thing with you and Miss Scalla, here—and I can’t say I blame you. What say I put it in tomorrow’s column as a new romance, hey?”

But it wouldn’t faze him, not for a minute. “Oh, I wouldn’t,” he’d say casually. “Matter of fact it’s just publicity.” He’d lean over conspiratorially. He’d whisper, “I need it badly!” And then he and Gia would see a good movie, for free, no less. And if things didn’t go right—the day after he’d be ready for the country again—and it would be there—waiting for him.

THE END

—BY BEVERLY LINET

George Nader will soon be seen in U-I’s Four Girls In Town and Joe Butterfly.

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE NOVEMBER 1956