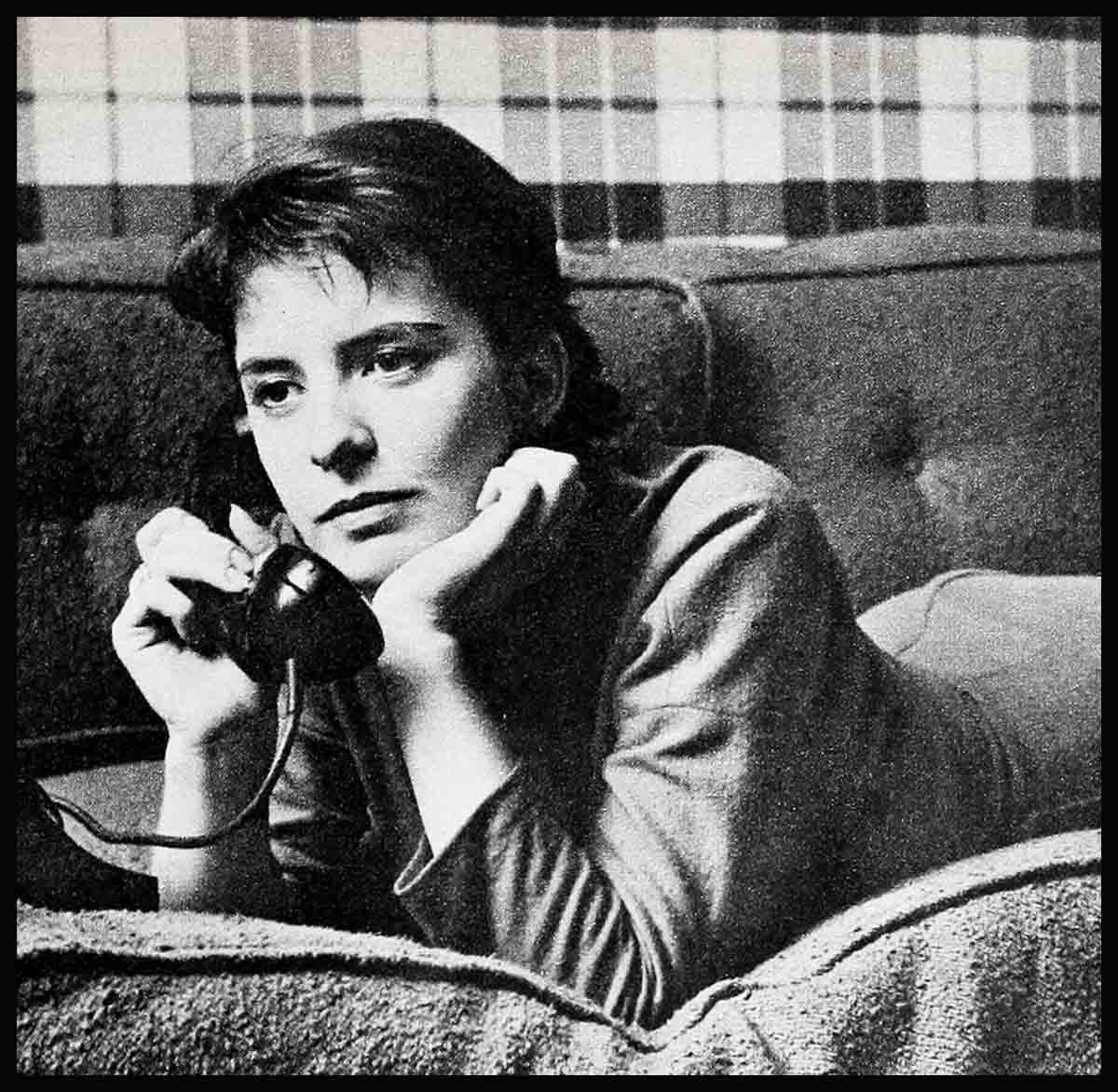

Margaret O’Brien: “Who Can I Turn To Now That I’m All Alone?”

The hospital corridor was dark and very still. A single light shone in the middle of the hall, casting a wide circle of light on the floor. At the far end of the hall, a nurse lit the desk lamp and glanced at her watch. It was time for her to make her early-morning rounds. She picked up her searchlight and started to walk along the corridor, the searchlight’s small beam dancing jerkily up and down as she walked. She checked the first two rooms, but walked past the third door knowingly. As she passed, the door opened and the nurse stopped and turned to see a girl about twenty step hesitantly through the doorway—her young body shaking as she tried to stifle the sobs that managed to escape her lips. She swayed for a moment, but the doctor who followed her grabbed her arm and she leaned weakly against him. The nurse shook her head and walked slowly toward the fourth door—there was nothing she could do. The doctor led the girl slowly down the hall, and, as they passed through the circle of light, the girl stopped for a brief moment. She felt the light surround her and for a moment she felt safe—it felt so familiar. Margaret O’Brien was again in a spotlight, but this time the drama was real—this time it was not make-believe—this time . . . it was true. Her mother had just died, and Margaret, for the first time in her young life, was alone, completely alone.

Suddenly, two small hands entered the circle of light and took her arm. She heard a soft voice whisper, “Let me take her into the lounge, Doctor. I will help her.”

“Thank you, Sister. I’ll be back in a little while to take her home.”

The nun led Margaret to the lounge and sat her down on the sofa. She smiled understandingly at her and began to speak in a very low voice—and as she spoke Margaret looked at her young face and stopped crying. She had never seen her before, but her words were right and good and Margaret listened.

“You cannot believe she is dead, can you?”

“No—no, I can’t,” she cried.

“Death is final, Margaret. And yet, I have seen you with your mother and I am sure there are many lovely memories to keep alive.”

“Yes,” she managed to say. “Yes, but you don’t understand. I need her so.”

“You must learn to stand alone. You’re . es girl now. We must trust to in this as in all things. I’m told you had a lovely day with your mother today.”

Today, she thought. Was it only today?

She looked at her watch. “It’s a quarter past three,” she said, not quite knowing why.

“My mother’s been dead now for . . .” And then she cried. “Why wasn’t I here with her when she died? I didn’t think she would die. She was coming home in a day or two. No one thought she would die.”

The room was silent. The nun leaned forward and looked at her hands—then she lifted her head and said, “I was told that you and a nurse wheeled your mother down to the hospital gift shop . . . yesterday.”

She nodded: “Yes, Mother loved to buy gifts for people.” She took a tissue from her purse and wiped her tears. “She bought a gift for my Aunt Marissa and a beautiful evening bag for me. She looked so wonderful. She was happier than she’d been in a long time. We sat talking for quite a while, and when it was time to leave, I told her, ‘I’ll be down tomorrow to bring some of your clothes.’ . . . And . . . she asked . . .”

“Asked what, Margaret?”

Margaret leaned back against the sofa and closed her eyes to keep back the tears and said, “She asked, ‘Am I really going home?’ I smiled at her and said, “Yes, you’re really going home.’ ”

They both believed it, and then, at 2:30 in the morning, the phone in her apartment rang and she heard the head nurse tell her that her mother had taken a turn for the worse. She dressed, got into her car and drove down alone. “I remember having a funny feeling all the way down,” she told the nun. “Dr. Ress—he’s our family doctor and close friend—he was waiting for me. He told me Mother was dead. ‘She couldn’t sleep, he had said, and, a little after two that morning, she had asked the nurse to help her to a chair by the window. ‘I think I’ll go back to bed now,’ she said, after about twenty minutes. She died without moving.” Margaret leaned forward and put her hands to her head. “Just like that.”

“It’s a shock to lose someone you love—unexpectedly, so suddenly.”

She heard the nun’s voice, but her thoughts wandered. Mother was only fifty-two. She was with you constantly. She did everything for you. Well, now it’s time to learn to do things for yourself, Margaret.

“At first, it will be difficult, and you will feel alone and will become despairing,” the nun told her. “But you will begin to see that your mother has prepared you for this day, and as you learn you will grow up and mature. This, too, will be difficult, but as you grow, you will learn to understand other people, and when you see the needs of others, with this, will come a freedom from fear.”

The door of the lounge opened and Dr. Ress came into the room.

Margaret wearily lifted herself to her feet and smiled at the nun. She looked so young—not more than twenty—and yet she seemed to have so much wisdom.

“Thank you so much,” Margaret said softly. “God knows you have helped me.” The nun smiled as Margaret O’Brien turned and left the room.

The early morning air was cool as Margaret walked toward the car. She was silent during the ride back to the empty apartment. Thoughts kept coming to her—there was so much to be done.

“If Mother had died in the apartment, I couldn’t stay there,” she thought. “I must make the necessary funeral arrangements. I must telephone Aunt Marissa in Fresno. I’ll have to meet her plane. Services must be held at the Good Shepherd in Hollywood. What about Mother’s things? Where will I find the strength to go through her belongings? I can’t do it! I’ll keep the medal His Holiness gave to Mother, and I’ll save that with the evening bag she gave me today. I will keep them forever.”

The car turned onto South Beverly Drive and came to a halt before the duplex that Margaret bought only four years ago, at her mother’s urging. She stepped out of the car and looked about her. It was the same as when she left. Only she was alone now . . . her mother wasn’t waiting upstairs for her. How do you survive when you’re all alone?

The doctor opened the door to the apartment and reached for the light switch. Light flooded the room. Margaret was home. She walked across the large living room and looked carefully about her, aimlessly touching vases and small knick-knacks.

“She had no pain, Margaret.” Dr. Ress had interrupted her thoughts. She turned to him and smiled shyly. “Remember, she would have been an invalid if she’d lived. She wouldn’t have liked that.

“Do you have any other relatives besides your Aunt Marissa?” he asked.

“Only a cousin in New York.”

They were both silent for a moment; and then she said quietly, “I know many people have heart trouble and live for years. Why did my mother have to die just now when my career suddenly has been going so well?”

Margaret had been working so hard she had been almost too tired to make the hospital, but she had gone anyway. “Thank God,” she thought.

They’d been inseparable, Margaret and her mother. Her mother never tried to hold on to her—those rumors hurt. When she went on dates, her mother merely suggested a reasonable hour to be home. “I chose my own friends, my own jobs, my own clothes,” she thought. “She was helping me—paving the way for the day that has now come. It’s just like the sister said.”

Her thoughts turned to Robert Allen. He was an aircraft designer and Mother had liked him very much. But they’d both agreed that it would be wrong to rush into marriage. “I want to be sure that marriage and a career will work for us,” she’d told her mother after a date with Robert. Now, was she sure? She’d have to make that decision alone now.

The room was so silent that Margaret was startled when the doctor suddenly asked, “Shall I call your aunt for you?”

“Oh. Thank you.” She was jolted back to the present. “Here, let me get her number. It’s over by the telephone.”

“What are you thinking?” the doctor asked.

She turned, looking at him timidly. “I’m almost ashamed to tell you. I was thinking of my future! Do you know, it’s come to me just now, that my mother has taken care of my future. I’m going to think very clearly about what has to be done. I don’t know what I have to say to people. I don’t know what is ahead of me. But maybe if I try hard, I can cope with it. My mother is still with me—she’s inside of me. She taught me so well—I should try to live up to her standards.”

And she began to shake and cry again, very softly. The doctor came to her and she leaned against him, like a child, and cried for a little while longer. Then she stopped and looked up at him with a little smile. “Dr. Ress, can you make coffee?”

“Why, yes Margaret. Why do you ask?” he said, with some surprise.

“I’d like to have some and, since we have time before we meet Aunt Marissa’s plane, I’d appreciate your teaching me. You see, I realize I’ve an awful lot to learn.”

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE DECEMBER 1958