The Whole World Over

TOKYO, JAPAN

Dear Pete,

What a welcome, finding your letter here at the hotel wailing for me! I’ll try to answer all your questions. First: What is it like over here?

I think the best way to answer that one is to tell you about a little incident that took place in a museum once. There was a fantastic “painting” there called “White on White.” I stopped to study it, and another man near me did the same.

“What do you think it is?” he asked me.

“I don’t know,” I said. “It looks like a snowstorm to me.”

“No,” he decided. “It looks more like a white building through a fog.”

Another man walked up and scoffed at the painting. “This is a masterpiece?” he said sarcastically. “A blob of white on a piece of white canvas? Anybody can do that.”

“I’m not so sure,” the superintendent of the gallery said, having overheard us. “People come here from all over and study it. They look at it and put their own interpretation on it. ‘White on White’ makes people think, and what they see is the result of their own thoughts.”

And that Pete, is what Japan—what any country or any person, for that matter—is like. To some extent we see our own thoughts, our own reflections, wherever we go. But as long as we question, as long as we think—whether or not we agree—we’re learning. So now I’m about to set out to learn about Japan so that I can answer all the questions I hope you’ll be asking. Remember, I’ll worry the day you stop asking questions. Your pal, Dad

TOKYO, JAPAN

Dear Pete,

Today down on the “Ginza,” which is the Broadway of Tokyo, I saw a Japanese mother in a kimono, with a beautiful, black-eyed baby strapped to her back, staring in a shop window, watching TV.

That answers your question about East meeting West. Yes, today the East and West are meeting here wherever you look.

You may be surprised to know that the Japanese are very sportsminded. For instance, Sumo wrestling is pretty spirited stuff. The rules state that one of the wrestlers wins when he throws the other bodily out of the ring! And when it comes to rooting—and rhubarbing—the Japanese are great baseball fans. The New York Yankees are even bigger heroes over here than at home.

Tokyo today has all the sounds and rhythms of both the present and the past. You see and hear and feel all around you the softness of Japan. The softness and the music of its voices, the cherry blossoms, the sampans floating silently along the canal. You hear the cry of the noodle vendor, the sound of a flute in the still of the night, the thundering rush of the subway, and the clickety-clack of wooden sandals pulling a rickshaw.

Yes, they still have a few rickshaws here, Pete. But I have no desire to ride in one. I’ve refused to ride in them or be photographed in them. I don’t like to see any man pulling another man. There is a respect for human dignity which we must honor wherever we are, regardless of the “style” of living in any particular land. I hope you’ll remember that always. Your pal, Dad

KYOTO, JAPAN

Dear Pete,

Youngsters in Japan are really on the move! I’ve never seen so many young sightseers. They begin to know their country at a very early age. We’ve been in Kyoto a few days, filming interiors for “The Teahouse of the August Moon” at the Daiei Company Motion Picture Studios, and every day new groups pour in.

The children travel in student groups of from twenty-five to 200, with their teachers in charge. The boys are dressed in their dark blue school uniforms, with brass buttons. They wear little billed caps. All the girls wear Standard blue-skirt-and-blouse outfits.

They’re spilling out of trains and buses every day, each of them carrying a little bag, and each with a stamp book carefully in hand. Youth hostelries—hotels for boys and girls—are a big thing over here, and every hostelry has its own stamp. The children take great pride in their collections and some of them have stamps from all over Japan. You see the youngsters marching along the cobblestone streets, singing as they march.

They go to Mount Fuji and to Tokyo. They go to Nara and its Todaiji Temple to see the famed Diabutsu, the biggest bronze Buddha in the world. They watch the women dye silks and rinse them in the river. Before a boy has reached his fourteenth birthday he’s often traveled the length and breadth of Japan. He’s studied and visited every important city and he’s developed a great sense of pride in his country and its traditions.

I was thinking as I write this, Pete, what a wonderful thing it would be for children in our country to take sightseeing tours like these. How great it would be if every boy and girl could visit New York and Washington, D. C., Mount Vernon and the Alamo, if they could explore all our places where the greatness that is America was made—and is still being made today. Your pal, Dad

NARA, JAPAN

Dear Pete,

Age in any form is at home here in Nara, and considering that today is my birthday, and I’m beginning to feel a little antique, this is just the place to be.

Nara is thirteen centuries old, the oldest city and the first Capital of Japan, and a treasure-house for the country’s arts, literature and history. We’ll be on location here for “Teahouse” for several weeks. M-G-M has built an Okinawan village right in the middle of a rice paddy about forty minutes drive from town. We’re using one hundred of the local people to portray Okinawans, and have twelve interpreters working with us. But language is no barrier here. The Japanese are so anxious to help us, so eager to please and to understand.

This I have learned in traveling, Pete: There is no actual language barrier between any people away from home. And certainly this is true in Japan. With a pleasant smile and a sincere “Thank you” you can travel anywhere in this world. “Domo Arigato,” which means “Thank you very much” in Japanese, is the most important phrase to know here.

Speaking personally, the only time there’s any language barrier is when I’m trying to order a hamburger! Don’t be surprised if we have nothing but hamburgers to eat for the first few weeks after I come home. I’m so hungry for them! I’m afraid a pleasant smile and a sincere “Thank you” hasn’t helped me to explain what a hamburger is over here. I tell them it’s ground-up meat cooked in the form of a patty—and they cook me a beautiful steak, then very carefully grind it up. I go through the whole bit again and I’m pretty sure I’ve made myself understood—and they cook another steak and then put it through the chopper. I’ve been getting more hash this way!

But that sort of thing is the exception rather than the rule, and it hurts them far more than it hurts me. Our Japanese friends are very embarrassed when they can’t understand you. They feel that they’ve failed terribly. If I order a boiled egg at the hotel and our little waitress, Suziko, brings it fried, she’s mortified. She laughs, but only because of a complete sense of bewilderment, and the laughter is very near tears.

The Japanese are a very sensitive people, Pete, far more sensitive than we have often supposed. They may not, for example, be able to say “Happy birthday” the way we would say it in English, but they know well enough what it means. And what it means to have a birthday far from home.

Today many of the Japanese sent me black-edged cards of sympathy! With their wisdom and sensitivity, they interpreted this not as a happy but as a “sorrowful birthday,” because I am so far from my family.

It was very touching and thoughtful of them, and no command of English could express it more fittingly. Your pal, Dad

NARA, JAPAN

Dear Pete,

Today is “Boys’ Day” in Japan. This is an important national holiday, and in my opinion it should be an international one. We have Mother’s Day and Father’s Day, why not Boys’ Day? I’m all for that.

The carp fish, or koi-nobori, as the Japanese call it, symbolizes great courage. And so carp-shaped streamers fly from the rooftops on Boys’ Day here to symbolize the strength and courage of all sons, and’ to encourage manliness and determination in overcoming all of life’s difficulties.

At this hour the sky around Nara is alive with carp streamers “swimming” from the bamboo poles. There are big ones in red and black, and white for the eldest sons, and there are small salmon-colored carp for the younger ones. In some yards there are several carp flying, one for each son.

We Americans are celebrating “Boys’ Day,” too. Since Danny Mann and Eddie Albert both have their young sons with them, we have two carp streamers flying proudly from the top of the flagpole out in front of our hotel.

I wish I could hoist one for you, but we’ll have our “Boys’ Day” when I come home. I’m bringing you a whole school of carp, including a fantastic black one. I have no idea how a fifteen-foot black fish will look flying from the yardarm in Beverly Hills, but we’ll fly it anyway. We shall probably be taken in for piracy— “Long Glenn Silver” and “Pete the Creep”! Your pal, Dad

NARA, JAPAN

Dear Pete,

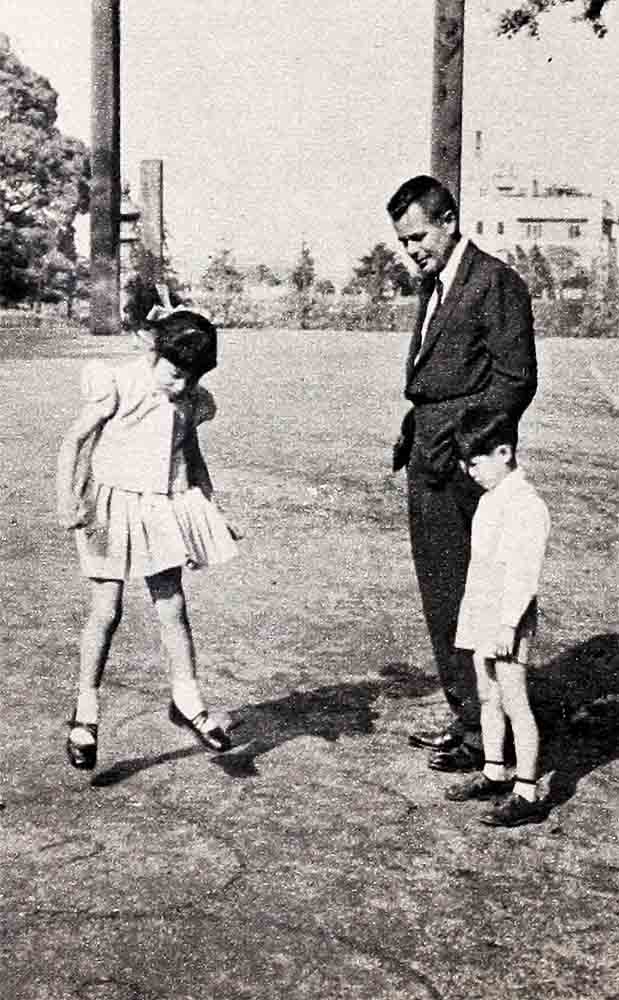

Tonight I had dinner with my “adopted son.” To adopt a member of another family is an old Japanese custom, I find, and I’m not just clear who has adopted whom, but every morning little Harashi Jiro is out on the set of “Teahouse” bright and early, and he spends the entire day with me.

Harashi is eleven years old—just your age—and we’re becoming very good friends. He’s a fine boy with a shiny round face, bright black diamond-shaped eyes, short-short hair, and he’s always smiling. He calls me Ford-san, which is the respectful manner of speaking over here.

Tonight Harashi invited me to have dinner with his family, and I know you would like to hear about this in detail.

When we stopped at the little bamboo and rice-paper house, the whole block where Harashi lives turned out to welcome me, each of them bringing me a gift of rice or raw tuna or something like that.

At the door of the hut Harashi’s mother asked me to remove my shoes. She set them carefully outside the door and invited me to come on in and sit down—on the floor. As is customary in Japanese houses, the floor was covered with a thick straw mat, called a tatami, and you sit on cushions, called zabuton. You eat on little teakwood tables about a foot-and-a-half off the floor, and it’s traditional to cook at the table. Each item is prepared on a hot brazier right in front of you, and between courses they give you a hot cloth with which to wipe your hands.

First they served green tea and brown rice-cakes wrapped in seaweed. Then came tempura, shrimps of a magnificent size dipped in a batter and fried. With it they served fried vegetables—string-beans, squash and sweet potatoes—all served in a little basket made of grass. The whole basket is dipped in a batter and french fried, and when you finish eating the fish you eat the basket, too! Believe it or not, fried grass is very good.

But we were still not through. They served raw red tuna and a big bowl of steamed white rice. This was followed with sukıyaki, which is strips of lean beef which you dip in raw eggs. The whole thing is prepared in a chafing dish with onions, bamboo shoots and other green vegetables. For dessert there were mandarin oranges, tiny little things served in sections.

After dinner they played games. While at first sight these games may seem strange to us, they become intriguing as you grow used to them. In Japan they specialize in games which test physical strength or muscular coordination, and in one they played tonight a girl balanced a plate with a pipe on it on her head. There’s a hand game in which your opponent holds two of your fingers and tries to catch your thumb. And there’s a wonderful game for two people played with a forty-foot rope. You stand twenty feet apart and try to pull your opponent off-balance. You tighten the rope, then release it suddenly, and the other guy tumbles on his back—you hope. This is a great game for getting into shape for my job as assistant scoutmaster of your Boy Scout troop.

Incidentally, you are now an honorary member of Scout Troop No. 4 here in Nara, and they’ve given me a special scroll to present to you. At the same meeting of Scouts in this area, they made me an honorary member of the Far Eastern Council of Boy Scouts, which takes in Okinawa, Japan and the Philippines. How about that? Your pal, Dad

NARA, JAPAN

Dear Pete,

Nara is a national park, and there are hundreds of tame deer roaming around—so tame they come up and feed right out of your hand. The deer are regarded as “divine messengers” here; they’re protected by the priests, and every evening a priest comes out and plays the trumpet to call the deer in. It’s a colorful sight, with hundreds of deer answering the trumpet, hurrying to their pens.

The Japanese are very religious, Pete, although some of their devout expressions of faith may seem a little strange to us at first because we worship differently.

During the commemoration of Buddha’s birthday, small images of Buddha are displayed in public, and a tea called amacha is poured over them with tiny ladles, to express the devotion of the Japanese. During the famous Hollyhock Festival, the leaves of the hollyhock are offered to the gods and goddesses in their shrines.

The Water-Drawing Festival is a time-honored religious rite here, too. This begins in the temple at midnight, with the ceremony of the Otzimatsu, or Big Torch, during which torches measuring thirty feet are lighted and young priests brandish them in firebaskets, shaking off the burning pieces. The believers rush for the fireflakes, believing them to have magic power against evil. At two a.m., to the accompaniment of ancient music, the priest draws water from the sacred well.

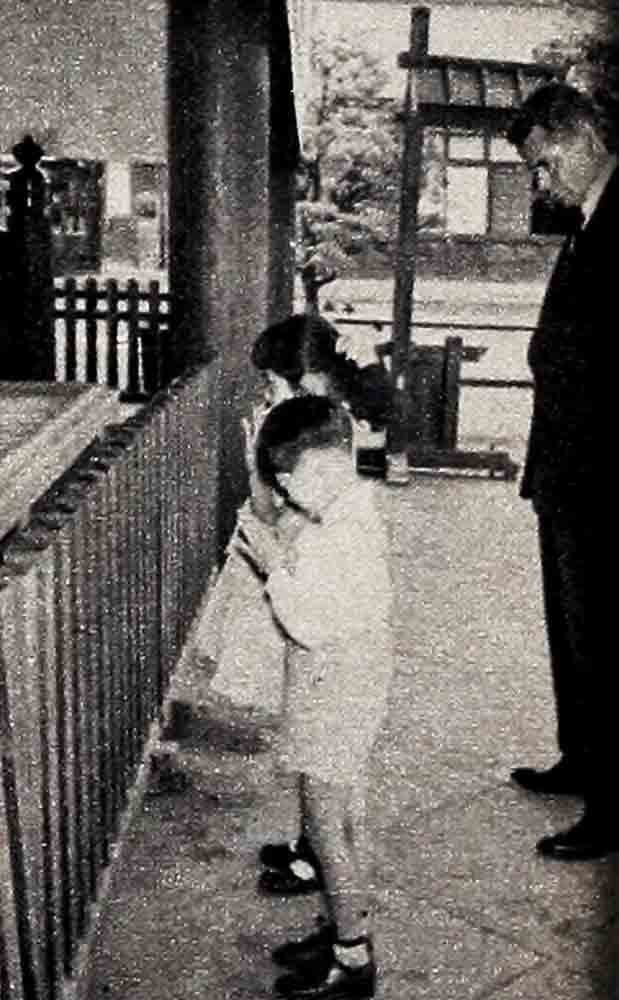

Every day I see children going to pay homage. They go to the temple, ring a little bell, and give offerings of lotus blossoms to the Great Buddha.

Seeing these things makes me feel more strongly than ever that to believe, to have faith, whatever form that faith may take, is the important thing. Someday that same faith that moves mountains may move men closer together again. Your pal, Dad

NARA, JAPAN

Dear Pete,

Today, something happened to me which brings to mind talks you and I have had.

This morning, driving out from town to the “Teahouse” set, we passed a very old Japanese man who’d fallen by the side of the road. His face was very gray and you could tell by looking at him that he was desperately ill. We stopped the car and I went over to see about him. But, ill as he was, something in the old man’s eyes stopped me, told me that he wanted no help from me.

The driver said we must leave him alone and drive on. “But we can’t just leave him here like this,” I said. “At least we can elevate his head, make him more comfortable.” But the driver insisted I must do nothing, not even touch him.

You see, to help him was the American way, but not the Japanese way, Pete. Even if he were in danger of dying he would not want my help. He would then feel indebted to me—a debt he would never be able to repay. This would mean loss of face and to him that would be worse than anything.

Sometimes it’s hard for us to understand another man’s way. Or another nation’s way. Just as it’s sometimes hard for children to understand another child’s way. You and I have talked about how cruel children can be, ridiculing or criticizing some kid who’s different from their own gang, who may dress differently or speak differently. You’ve never done this, and I’m sure you never will.

Human nature being as it is, we are sometimes tempted to ridicule or criticize something we don’t understand, something which is different from our own accepted way. This can be very serious and can lead to intolerance of those who are of a different color, a different religion, or a different economy.

The world is full of all kinds of people, and they aren’t all people like Glenn or Peter Ford. If we want them to respect our way of life, then we must respect theirs. Your pal, Dad

NARA, JAPAN

Dear Pete,

We’ve been having so much “unusual weather” here that we’re breaking up camp and coming home!

Now that we’ll soon be saying “Sayonara”—which means goodbye in Japanese —I can think of so much I’ll miss.

I’ll miss all the sounds—of the shutters closing at night, the tinkling of the wind-bells, and the constant clickety-clack of wooden sandals going up and down the cobblestone streets. And I’ll remember all the beauty that is Japan’s.

But most of all I’ll remember the people, their gentleness and their generosity. Our Japanese crew on “Teahouse” cried unashamedly today on the set when we had finished the last scene. We have become very close, working together during all this time. They just stood there looking at us and saying “Sayonara,” with tears in their eyes. I can’t tell you, Pete, how moving it was.

And there’s little Suziko, the waitress at the hotel, who’s been wonderful to us. This morning she handed me a note, very carefully written in English, saying she’d like to see me. “I see you out front,” she said, and darted away.

As I was leaving the hotel, Suziko suddenly appeared from nowhere and handed me a package. “For my Tomo Dachi,” she said, meaning “dear friend.” I opened it, and there was a beautiful geisha doll which must have cost all of 3000 yen. That’s two weeks’ salary, a lot of money for a little girl who’s just fourteen. But you can’t refuse to take it. That would be the worst thing you could do.

Suziko’s concern was what would happen with it. “Where you keep doll?” she wanted to know. I told her that I would put it in a very honored place where I would see it every day. Then she skimmed away down the path.

When I’m at the other side of the world, back home with you, Pete, I’ll remember many things. And whenever I think of the gentleness of Japan, I’ll think of a little girl named Suziko, who’s the symbol of all the lovely children over here.

I’ll remember all the scenic splendor of the Orient, the mountains, the temples, the pagodas, the cherry blossoms and the old, old beauty everywhere. But you don’t find the true beauty of this country in travel folders. The beautiful thing you can’t take pictures of is the beautiful heart these people have. See you soon. Your Pal, Dad.

THE END

Look for: Glenn Ford in “Teahouse of the August Moon.”

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE JANUARY 1957