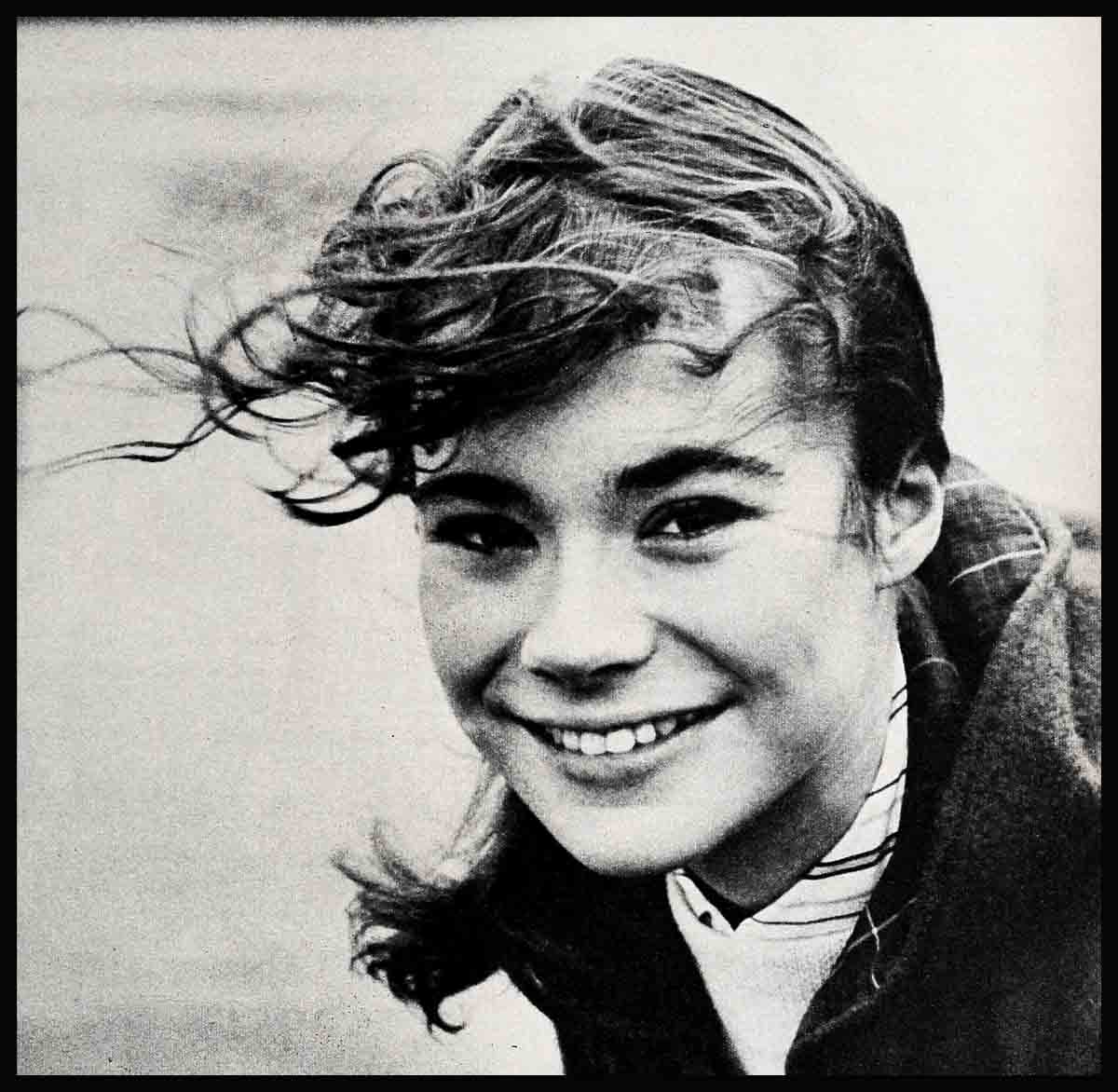

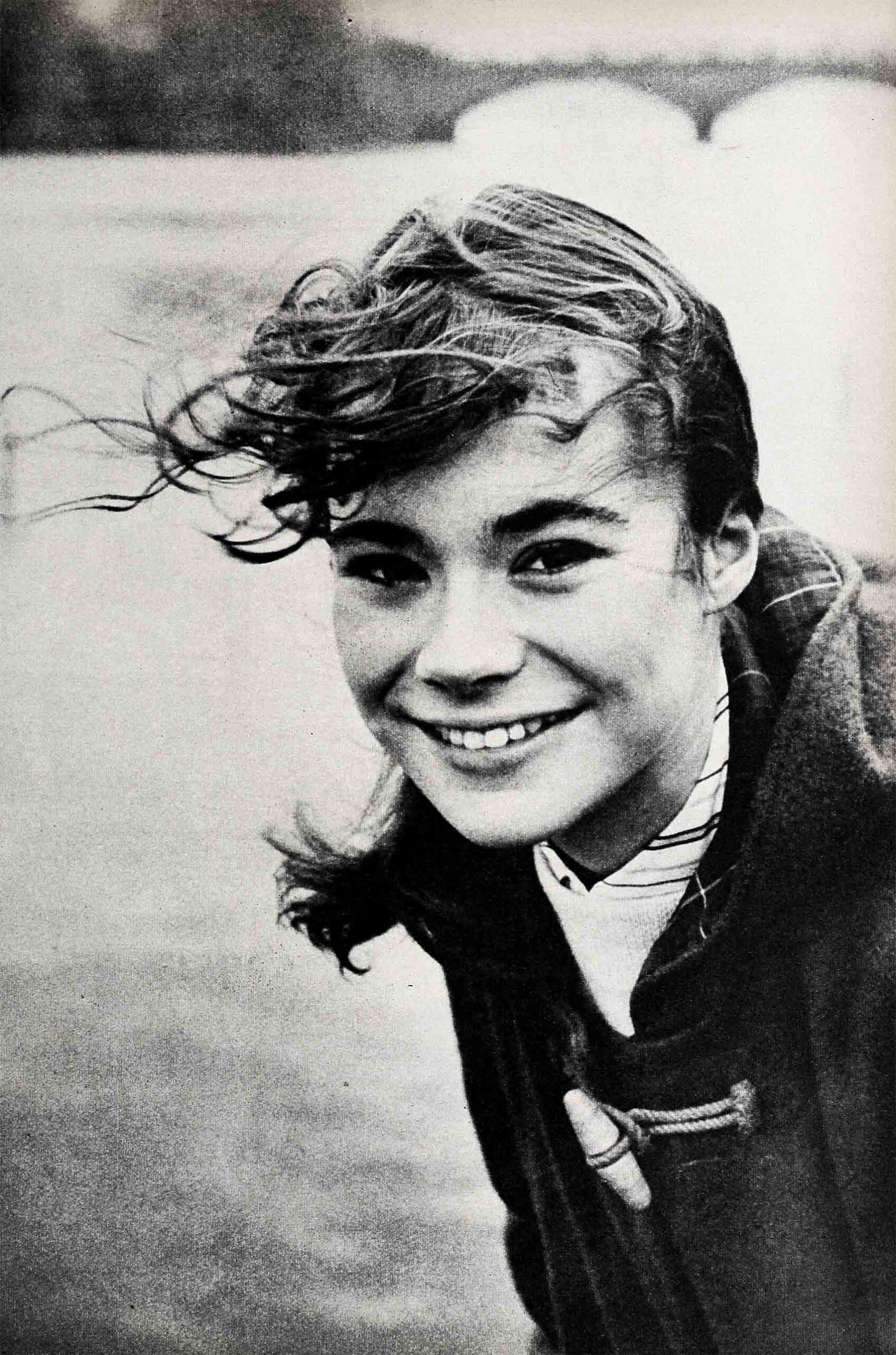

Here’s Heather Sears

An aura of excitement swept the plush London theater. It was a premiere atmosphere, electric with furs and perfume and chic-coiffured women with well-tailored men. Suddenly, their din of polite chatter softened to tense silence as the houselights went down.

Dr. Gordon Sears, one of London’s eminent physicians, sat with his wife and eldest daughter, Ann, in the theater’s special section. Within seconds, the lights were out, the music began and “The Story of Esther Costello” soared across the huge screen.

This was it, thought Mrs. Gordon Sears uneasily as she watched the screen credits unfold. And, as if he sensed her anxiety, her husband gave her hand a reassuring squeeze. “Don’t fret,” he comforted softly. “I think it will turn out fine.” The next few hours would be the result of the past months of anticipation and wonder, Mrs. Sears thought. And she could not help going over in her mind the events of those months.

She remembered that first afternoon, when Heather got the role. Heather, perennially gay and lighthearted. No, she never thought her youngest daughter had the determination to study the Braille method; to learn a whole new set of perceptions, those of a deaf and blind girl who is also mute; to develop that difficult a part to its fullest. And she remembered the afternoon, not long ago, when Heather came home from location and burst through the front door in tears, exasperated because she felt she was grasping her Braille lessons to slowly.

Well, too late now to worry about it, she told herself, and she let her thoughts trail off and become absorbed in the film.

Two and a half hours later, the house-lights came up and soft whispers broke the tense silence. Mrs. Sears, who had cried at the pitiable Esther, along with the rest, brushed her tears away, turned to her husband and remarked in amazement:

“I—I can hardly believe it. I always thought Heather was the funniest child ever born.”

Obviously, Heather Sears is many things to many people. She’s a five-feet-two inch brown-haired, brown-eyed, twenty-one-year-old mass of contradictions. The contradictions aren’t intentional. They’re simply Heather.

Wearing a plain tan skirt and plaid duffel coat, she can melt into a crowd with no fear of being recognized as a star. But when she dresses up, she stands out like an animated cover of Vogue, and she can be every inch the movie personality—if she really puts her mind to it.

With family and friends, she’s a reformed tomboy and a tease. With strangers, she tends to be shy. Perhaps it’s because she’s met so many strangers lately and stardom is still too new for her to accept with complete comfort the sudden attention and adulation brought by fame.

In any event, Heather’s no waster of words. If she has nothing to say, she’s politely silent. Providing she’s awake. In Frankfurt, Germany, on the second day of a recent personal-appearance tour, she began to quiz the lady publicist with whom she shared a room. “Did you go right to sleep last night?”

The publicist admitted that she had, much to Heather’s disappointment. “I talk in my sleep,” she explained. “And the next day I always wonder what I might have said.”

The publicist could never enlighten her, as she invariably dozed off before Heather began her nightly monologues.

Awake, she’s not one to beat around the bush, provided there will be no wounded feelings. However, her mother recalls one of Heather’s lessons in diplomacy with mixed emotions.

During the war, Mrs. Sears and her daughters were evacuated to Llanfairfechan, Wales. When Heather was seven, she and her sister Ann organized a neighborhood carnival in the garden, to raise money for the prisoners-of-war fund. Heather was appointed fortune teller, and before the grand opening, her mother took her aside for a little talk. “I want you to be sure and say nice things to everyone,” she warned her daughter. “No matter how you feel about them.”

Heather was quite agreeable. Since then, as now, she adored babies, she decided that the nicest thing she could predict would be prospective parenthood. That day in Llanfairfechan, according to Heather, everyone was going to have a baby almost immediately. The group included bachelors, bachelor girls, oldsters, youngsters. And if Heather was particularly fond of someone, that someone was informed that he or she could count on quints!

Heather was equally as certain of her own future. She would have children—lots of them—but first she would become an actress. “When we were small,” she remembers, “my sister Ann and I used to get up in the morning and right away be characters from a book we’d read, or somebody we’d seen in a film. We were never ourselves.”

Ann, an English star in her own right, never ceases to marvel these days when she hears the poised Miss Sears answer questions with the tact of a diplomat. Ann has been called “the prettiest girl in London,” but there was a time when she thought she was doomed to be the homeliest. Dubbed “Mop” by the family, she was constantly consulting her mirror to see if she could find even a faint resemblance to the girls’ idol, Rita Hayworth. Once, when the mirror failed her—or vice versa—she turned to Heather for some sort of assurance. “Do you think I’ll grow up plain?” she asked worriedly, a frown crossing her face.

Heather studied her sister for a long moment, then delivered her opinion. “Oh, I’m sure of it.” After another moment of thought, she added. “Yes, Mop, there’s not a doubt in my mind. You’ll grow up plain, all right. Awfully plain.”

Thus spoke the personality who received accolades from the critics, but who to her London hairdresser is probably the world’s worst actress—offstage. One afternoon, ordered by the studio to have her long hair cut, in favor of a more chic style, Heather dutifully appeared at the beauty shop. The hairdresser picked up the scissors and began to snip away at her beloved ponytail. As her hair got shorter, Heather’s face got longer. At last, when she could control her unhappiness no longer, two large tears appeared and started to roll down her cheeks. The hairdresser began to feel like the butcher of all time, a heartless cad.

Catching a glimpse of his face in the mirror, Heather murmured unenthusiastically, “It’s lovely,” feeling obliged to cheer him up. “It’s going to be just lovely. I’ll be just crazy about it,” she assured him dramatically. But somehow, the words coming between sobs, just weren’t convincing.

When Heather and the hairdresser parted company, they were quite possibly the saddest pair in the whole of England. “It is nice,” Heather tried once more.

“Yes,” answered the hairdresser glumly.

“Well, goodbye,” said Heather. And then, “How long do you think it will take to grow back again?”

“I suppose our looks were so terribly important to us,” recalls Heather, “because we used to go to the cinema so often. The first program began at five, which meant we’d be home by seven, and we’d rush down after school. Mother never objected. I think she was happy to get us out of the house for a bit.

“We’d never heard of Hollywood and knew nothing about the way movies were made. When we discovered them, we saw ‘Random Harvest’ four times, and were amazed by the fact that important people like Greer Garson and Ronald Colman could find the time to come all the way to Llanfairfechan to act behind our neighborhood screen.”

Heather, herself, preferred the character of Tarzan. (“I almost always got around to being Tarzan,” she recalls. “Or a horse.”) Because of her passion for horses, her acting ambitions were once temporarily put aside. “For a brief spell I thought I wanted to be a mounted policewoman. Then,” she says, “I found out that there were no such things as mounted policewomen and that more or less settled the matter.”

The idea of acting first came to Heather at the age of five, when she and Ann appeared in their first big production in Llanfairfechan. “Everyone told us we were terribly good and it went to our heads,” she grins.

The show was “Peter Pan” and Heather had the role of Michael. The general idea was for her to make her entrance astride a large dog. However, the performance didn’t go off as planned. The moment she made an appearance, the delighted audience broke into applause. Heather, in turn, was delighted to have such a nice audience. She began to clap, too. Off stage, the play’s director was hissing, “Heather . . . Heather . . . get on with the lines . . .”

By the time the director was in the initial stages of a nervous breakdown, Heather remembered her mission and went on with the show as per rehearsal.

Following her first triumph, Heather began taking note of the practical side of the acting game. During the war years, sweets were scarce except, it seemed to Heather, at the gates of a nearby Army camp, where evacuee children gathered to be deluged with candy bars by the generous soldiers. Heather had been strictly forbidden to ask anyone for candy, and she can honestly say that she never did. “I simply donned my oldest clothes, assumed a hungry look and joined the small-fry crowd at the gates. And came home with a fist full of candy bars every time,” she recalls, good-humoredly.

At the age of eight, she was writing plays and selling them for pennies to Ann and the neighborhood children. “There were conditions, however,” recalls Heather. “I insisted on a contract stating that whenever one of my productions was produced, I be allowed to play the little king with the beard. The little king with the beard invariably had a large part.” Today, Heather’s seven-year contract with Romulus Films is another shrewd triumph. It allows her an annual six months to do stage and television work if she wishes.

An individual in childhood as now, if Heather could have been described in a word during her formative years, that word would have been tomboy. She never stopped begging for a horse of her own, and she had a tendency to climb every tree she came to. Under pressure, she’d agree to wash her face and have her hair brushed until it shone, but she was cagey about the business of getting dressed up. Ann still tells about the time Heather accompanied her to a party. “From the neck up, the youngest Sears looked perfectly lovely,” she recalls. “However, when the hostess’ mother took her coat for her, Heather was a standout in the crowd of guests. She had chosen to wear a pair of old rumpled shorts and a sloppy sweater! I was mortified.”

In this respect, Heather hasn’t completely changed. A Columbia Pictures executive enjoys telling about the phone call he received from Heather when he was in London recently. “The phone rang and it was Heather,” he recalls. “The conventional Miss Sears was wondering whether she might attend a midnight preview of ‘Esther Costello’ in blue jeans!

“ ‘Blue jeans!’ I bellowed, and, gathering my patience, explained to Heather that the event was a swank sort; the cream of the British movie industry would be there.

“ ‘Oh!’ she said meekly. ‘The invitation says to dress informally and I thought perhaps it meant . . .’ Her voice trailed off sadly.”

Heather’s opinion of sister Ann is just the opposite. “Ann was always so dignified. Secretly I couldn’t help being impressed because somehow she was everything I wasn’t. But I kept the secret well. I teased her unmercifully.”

Heather’s favorite form of torture was to wait until Ann had rolled up her hair and cold-creamed her face and then break into helpless laughter at the sight. “It was a nightly ritual and Ann was at a disadvantage because if she raised her voice she’d wake our parents,” remembers Heather. “One night she settled for throwing an alarm clock. When it actually hit me, Ann burst into tears. For the next few weeks, she took all teasing and allowed me to follow her around, with no backtalk. I took full advantage of her guilty conscience,” Heather admits.

“Heather was always tagging along,” remembers Ann. “My friends and I used to try and tell her that she was a delicate child and couldn’t stand up to the ruggedness of our outdoor life. But it never worked. She decided that she’d prefer to court death rather than leave us alone.”

At eleven, when Ann began to take elocution lessons, nine-year-old Heather insisted that she have some, too, although she wasn’t quite certain what they were. When she was sixteen, she followed Ann to the Central School of Speech and Drama. At the time, it was a difficult decision. She loved history, and she’d read every book she could find on Disraeli. “At first I thought I might like to go to the university and study, then take up acting. But I changed my mind because I wanted to be an actress so badly I couldn’t bother to go to the university first,” she says.

Mrs. Sears was enthusiastic about her daughters’ careers. Dr. Sears, resident physician at London’s Mile End Hospital, was somewhat less than enthusiastic. “Mother had wanted to act, but her parents wouldn’t let her,” Heather explains. “Father wanted Ann to be a doctor and me to go to the university. He wasn’t pleased about the idea of having to support us for the rest of our lives,” she grins. “But now he seems very happy.”

As a matter of fact, when Ann and Heather began to wonder if two stars named Sears might be one too many, it was their father who settled the argument. “There will be no name changing,” he declared. “The name Sears has been good enough for me and it was good enough for my father, his father and his father. It’s good enough for the two of you.”

And it was. It was during Heather’s last year at Central that she was seen by a Romulus Films casting director and signed to a contract. She had small roles—“one or two lines”—in two pictures. She did stage work with the Windsor Repertory Company and the Cambridge Repertory Theater. She drew her first raves from the critics for her portrayal of a confused adolescent in the television show “Death of the Heart.”

And she won an invitation to join the scores of young actresses testing for the coveted role of Esther Costello.

While awaiting the results, Heather divided her time between painting pictures and sitting beside the telephone. She had no idea what might be happening at the studio. She knew that Joan Crawford had arrived in London and that the picture would start as soon as an Esther had been found.

The Sears’ large hall clock said six P.M. the evening the telephone rang and Heather heard the words she’d prayed for: “We want you to come over to the TV studio for an interview with Miss Crawford. You’ve got the part.”

Later, she was told that Miss Crawford had stopped by the studio projection room to watch some of the tests being run. One of them was Heather’s, and when it was over and the lights went on, Joan Crawford was the first to speak. “There’s no need to test anyone else,” she said. “This girl is your Esther Costello.”

The role of the blind deaf-mute was like none Heather had ever attempted. “Actually it wasn’t like working on a part at all,” she says. “It was like learning something completely out of one’s normal range.

“I had a teacher who taught me to read and write in Braille. I studied the hand alphabet. The teacher and I talked and talked and talked about the reactions of blind people. I built up a complete mental impression of their lives and what they’re like.

“It gave me an awareness of their problems, how they feel about things. I never really had to think how Estherwould react to certain things. It was something I knew. It was a part you couldn’t act. You had to live it.”

She still talks about the kindnesses of Joan Crawford and Rossano Brazzi. “Miss Crawford was wonderful. I learned so much from her. Things that were a help on this picture and acting hints I’ve tucked away in my mind and will use when I need them on other pictures.”

Rossano brought a touch of humor to the set happenings when Heather turned twenty-one. “It was the afternoon they were scheduled to shoot the scene in which he assaults me. In my dressing room that morning,” she remembers, “I found a large bouquet of roses and a note reading, ‘I’m sorry that I have to do this to you on your birthday.’ ”

“The Story of Esther Costello” brought Heather fame and critical acclaim. The picture also brought unexpected romance. Before the start of the film, Heather was introduced to its talented art director, Tony Masters. He looked down at her and was enchanted. She looked up at him and got a crick in her neck. “When I first saw him the only impression he made on me was that he was tall—he’s six-foot-six—and had a tremendous sense of humor,” she claims. “And I thought it would look a bit quaint to be seen with someone that tall.”

According to Ann, however, Heather came racing home one weekend in a daze. “Ann . . . I’ve met the most wonderful man. He’s so good looking. And he loves horses!”

During the production Heather and Tony lunched together daily. “And we saw a lot of each other on the set, although we didn’t have time to talk a great deal. After shooting, we’d have a cold drink together, then I’d go back to the hotel. We went out only two evenings during the whole film.”

They’d been dating for several months, and the picture was completed, when one night, out of the blue, Heather astounded the gentleman with, “Tony, I want you to propose to me.”

“You what?”

True, they had both begun to take it for granted that they were going to marry. In fact, they were considering themselves almost unofficially engaged. “But it’s the only proposal I’m ever going to get and I think we should do this properly,” said Heather. “I want you to say the right words.”

Tony said the right words and they were wed last April. “I rather imagine I would have married him anyway,” grins Mrs. Masters.

Has Tony solved the “puzzlement” that is Heather Sears? That’s another story—a long and happy one, let’s hope.

THE END

—BY BEVERLY OTT

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE FEBRUARY 1958