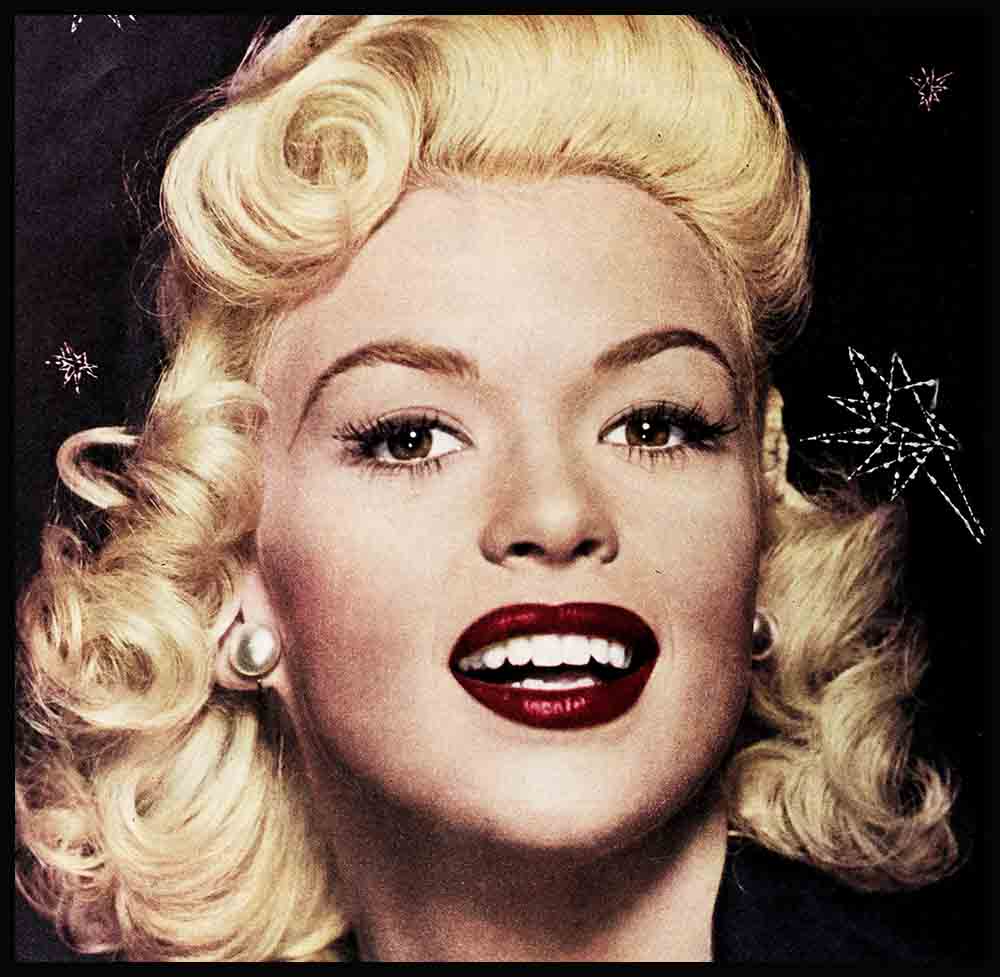

All She Wants To Be Is A Movie Star

Miss Jayne Mansfield, whom you will be seeing in the 20th Century-Fox picture. “The Girl Can’t Help It,” has always wanted to he a movie star. Ever since she was a very little girl in Bryn Mawr, Pennsylvania, a slightly less little girl in Dallas. Texas, and a spectacularly big girl, first on Broadway. New York, and now in Hollywood, California, she has wanted to be a movie star.

“I could taste it and smell it and live it.” she told a friend recently. “First I wanted to be an actress, then I wanted to act, now I want both. But especially to be a star.”

AUDIO BOOK

Nor did she want this in the approved. simpering manner. known here and there as the Art-Is-All-Money-and-Autographs-Nothing approach. She wanted to be a star in the grand old manner, the nearly forgotten scope for which Hollywood old-timers sigh nostalgically. She wanted—she knew she wanted—a pink Jaguar, a glass house, excursions to Vegas and Palm Springs and Mocambo, a wardrobe of a sort that would turn Joan Crawford frumpy. The pattern was crystal clear, the determination awesome. In fact, it was inflexible: Today she drives a pink Jaguar, lives in a glass house, dresses like a model who never had time to change to something simple, and may well be in hock up to her ears as a consequence. The trips she had—and has—planned wait only on the completion of her picture. Miss Mansfield is, at last, a movie star.

But there also existed in Jayne Mansfield a geographical confusion. Stardom to her meant Hollywood and only Hollywood, and to be torn away from it for any reason was unthinkable. Hours spent in such nearby outposts as Compton, California, where she lived as a yearning bit player, gave her a sense of time and opportunity fleeing; and certainly it never occurred to her that the straight line from Schwab’s drugstore to a film contract ran through Times Square.

Therefore, it was with a mixture of foreboding and indifference that she agreed to audition for a sexy comedy part in a projected Broadway play by George Axelrod called “Will Success Spoil Rock Hunter?”—the play was, nastily enough, a spoof on fan magazines and their writers. Her indifference was due to the fact she was sure she wouldn’t get the role, her foreboding to the wild suspicion that she might.

History, of course, knows the answer. She did. Her agent called her, jubilant with the news. His client placed a hand against the wall to keep from fainting from pure chagrin. “You can’t mean it,” were her grief-stricken words.

“I can remember my feelings so well,” Miss Mansfield has recalled. “New York! It was like going to—oh, to Yankton, South Dakota, or lower Tibet. It was as far from Hollywood as I could imagine. Besides, I didn’t want to set Broadway afire, or whatever they call it. I wanted to be a movie star. When the agent said this could be the wedge, I didn’t believe him. Can you imagine, it was the second lowest moment of my life!”

And what was the lowest?

“Well, that’s part of it. Maybe if the lowest hadn’t happened, I wouldn’t have gone, no matter how much my agent urged me. But I’d been let out by Warner Brothers. That was the lowest. I wanted to die. Not in any active, suicidal sense, but just in the way you want to stop living when everything is gone, every hope. You have to understand. I want to be only one thing—a movie star—and if I couldn’t be that, I didn’t want anything.

“Then a friend came over to the apartment, the man I was dating then, and he brought me presents and cheered me up and convinced me this wasn’t the end of the world, even though I knew it was. So that made it both the worst night of everything and just a kind of turning point. If I had been alone, I might have quit entirely inside. But he was there and I’ll always love him for it. Just being there. There are moments when a person should not have to be alone, and that was one of them.”

In point of fact, Jayne’s screen career at that moment was not prepossessing. She had appeared for Warners in three pictures: “illegal,” “Pete Kelly’s Blues” and “a dreadful thing called ‘Female Jungle’.” The quote is Miss Mansfield’s. And that last is in for a frantic session of re-releases, now that Miss M. is on the verge of becoming a household name.

After her release from Warners, Jayne made an independent with Dan Duryea titled “The Burglar.” After that, “Rock Hunter” came into her life.

Actually, there was no formidable reason for Miss Mansfield to dread “Rock Hunter.” In the first place, she had had some stage experience in high school and college (where one more semester will get her her degree). She had also worked out with little theatres in Dallas. And finally, she is a young woman of great poise and assurance and belief in her abilities, not at all the dumb if imposing blonde of her professional characterization. Nor did she dread it as a dramatic assignment. What troubled her was simply the sense of isolation from her beloved Hollywood.

But neither did she expect what happened: the brilliant success of the play and New York’s amused, uproarious embrace of Jayne Mansfield, of whom it had never heard until then. It happens once every Broadway season, once in a while twice. This time it was Jayne Mansfield.

But how had it happened? Surely not by public acclamation alone?

“Oh, no,” said Jayne, who is a forthright girl. “There has to be something else. Well, it all began with the press. Especially the columnists. They were all so wonderful. Then I—well, I did quite a lot of promotion myself. It seemed I was always promoting. Snipping ribbons, shoveling the first dirtful for a building foundation—oh, anything, I guess. You might call me ambitious. Not ruthless. I’d never hurt anybody else. But ambitious. I could see then how the play was going to help me be a movie star, and that made everything all right. I was seen in the right night clubs, the Stork and 21 and El Morocco. That was part of it. You see, I’m speaking frankly. This isn’t the usual way they talk, is it?”

No, not exactly. But would Miss Mansfield venture to go even a little further and explain the welter of daring still pictures of her that suddenly inundated the market?

She laughed delightedly. “Aren’t you cute? Well, that was part of it, too. There was more than one market to sell to. The middle-aged women, for instance—you know, they liked me! That would be one kind of Jayne Mansfield. Then for teenagers, another. And for the men, what you just said—the cheesecake.”

In New York, when Jayne was not promoting herself vigorously or distracting theatre-goers, she was wandering in Central Park with her daughter Jayne Marie, now six, or haunting her beloved motion picture theatres. The dream within her was as strong as ever.

There were few suggestions of romance, except for inconclusive newspaper accounts involving Mickey Hargitay, a professional strongman then employed in the night-club nip-ups of Mae West. Jayne, who on October 23 won an interlocutory decree of divorce from Paul Mansfield, whom she had married in Fort Worth on January 28, 1950, usually declines to comment on Hargitay, explaining only that his presence on the same plane with her when she arrived back in Hollywood was “a coincidence.”

“Will Success Spoil Rock Hunter?” threatened to run forever, but Miss Mansfield finally was pried loose from her contract and landed back at Los Angeles’ International Airport in triumph, no longer the obscure blonde who had left via the same runway. The press reception was clamorous, Fox spokesmen were deferential, and Jayne herself, never seeking to be inconspicuous, had on hand a large share of her extensive menagerie, which includes a Great Dane, a Scottie, two Chihuahuas, a toy poodle, three cats and a rabbit. Only the rabbit couldn’t make it. Jayne was carefully dressed for the occasion, causing television viewers of the arrival to leap from their chairs in amazement. Mr. Hargitay remained more or less in the background.

Jayne went right to work, this time co-starring with Tom Ewell and Edmond O’Brien. For her, the Hollywood air was sweet with jasmine and the heady scent of ultimate victory.

“I’ve had three wonderful breaks,” she recounted the other day over a lunch of fresh orange juice with just a little lemon added. “The first was being born. The second was that ‘Underwater!’ junket. The third was ‘Rock Hunter’. You remember the junket, of course?”

Her listener did. The “Underwater!” junket took place in January of 1955. It consisted of a flight of four planes— two from New York, two from Hollywood —to Silver Springs, Florida, on behalf of the world premiere of the picture “Underwater!” starring Jane Russell and Richard Egan. A handful of starlets went along to help sell the picture. So did Debbie Reynolds, as well as stars Russell and Egan. Miss Mansfield not only was there, she stole the proceedings.

This Jayne did solely by means of her personal activities plus one prop—a bright red bathing suit apparently a size or two too small for her. The photographers shot until their trigger fingers were numb. The starlets stood around and sniffed. But the art that ensued had national impact. It was serviced to every newspaper and many magazines—and promptly snapped up by a great number of them. After that few people knew who Jayne Mansfield was, perhaps, but everybody knew what she looked like.

As a matter of fact, nobody in the “Underwater!” party knew exactly what Jayne was doing there. She wasn’t in the picture, and she didn’t even work for RKO, which made it.

During much of the flight back to Hollywood, this writer sat beside her. He was impressed at first only as any male would be with so much spectacular femininity. But later there became apparent the sense of urgency that filled her, the almost pathetic ambition—except that it was more than ambition. It was a dedicated drive. If she wasn’t going to do it one way, she was going to do it another—within decent reason. Although fatherly advice of the Why-don’t-you-go-back-to-Dallas sort is customary in these circumstances, the writer said nothing. It was too good a guess that she was going to do it. Later, young and adjustable, she slept like a child in her seat while the rest of the party wore themselves out doing nothing.

“And you see I was right,” she said now, sipping at the orange juice with a little lemon. “I’d worked and studied and nothing happened. So I went to Silver Springs and put on a red bathing suit, which anyone can do, and lots happened.”

They surely did. Agents and studios grew interested, but while they were yakking about it, Warners stepped in. But then, as recounted, stepped out again. And by and by, “Rock Hunter” took over.

Yet Paramount could have had her first. That, by Jayne’s personal account, is not only true but a somewhat bizarre story.

She turned up in Hollywood in September, 1954, without much behind her but the title of Miss Photoflash of 1952, three years of education at various colleges (Southern Methodist, University of Texas and UCLA), and the burning urge for stardom. She had a baby and a husband and a smattering of invincible gall.

“I called Paramount right away,” she remembers now, “and asked if they had any opening for a movie star. They said they already had a movie star. But they were so—well, I guess staggered—by the approach that they did ask me over for a test. They really did. And I took one. Nothing came of it—I didn’t look a bit like Jayne Mansfield then, just a mousy girl. But later on a man who saw me in person said he’d give me another test any time. I must have shrugged or something. How should I know he was Samuel Goldwyn?”

Nor did she look especially like Jayne Mansfield, the Jayne Mansfield of “Rock Hunter,” on a Fox stage a few weeks ago. Her features had refined, her waist was willowy and she was quite well battened down in front. But the change was for the better. So was the acting, compared with what had been in the Warners and independent days. She played a scene with co-star Ewell that demanded wistfulness, loneliness, plus a naive and touching lack of knowledge of what physical assets could mean. It was a long scene and intricate. It was handsomely done.

When it was over a Fox spokesman said: “She’s going to make it. She has right now what she finally came around to wanting—to act and to be an actress, both. Of course, she’d better make it. She’s a gambler, you know. That silver mink coat of hers cost $20,000. The home in Beverly Hills isn’t for nothing. Her wardrobe’s by Oleg Cassini. You think she has that kind of money? She runs herself in debt because she’s sure it’ll pay off. The studio has her down for $75,000 this year and naturally that ain’t hay. But you can always drop an option.

“But she’s going to make it because she’s young and because she wants it so badly. Maybe it won’t always be that way. Betty Grable got older and really stopped wanting it. She’d had it all. Marilyn Monroe—well, who knows Marilyn? But this one, I’ll bet my shirt on her.”

“This one,” about whom there is precious little more to say, was born Jayne Palmer in Byrn Mawr on a certain April 19, twenty-three years ago. Her father, Herbert Palmer, died when she was a child, and her mother later married a man named Harry Peers, a sales manager who moved the family to Dallas. Jayne was six then.

In Dallas, she attended University Park grammar school and Highland Park High. When she was sixteen and still a high-school student she married Paul Mansfield, a classmate. Jayne Marie was born to them on November 8, 1950.

The Mansfields attended together the three colleges mentioned, Jayne maintaining a highly respectable “B” average throughout. She would like to get her B.A. degree, time permitting. One semester will do it.

In 1955, the marriage came to grief. Jayne prefers not to discuss why. She filed suit in Los Angeles Superior Court for separate maintenance. Later she amended this to read divorce. Mansfield contested both actions, but later withdrew his objections and Jayne obtained an uncontested divorce.

Our heroine is a fair linguist, speaking Spanish and German. She is something of an athlete, and a musician of interesting attainments, particularly with the violin. She is an actress, too. But first, last and foremost, she’s a movie star.

That’s the way she planned it.

THE END

DON’T MISS: Jayne Mansfield in 20th Century-Fox’s “The Girl Can’t Help It.”

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE FEBRUARY 1957

AUDIO BOOK