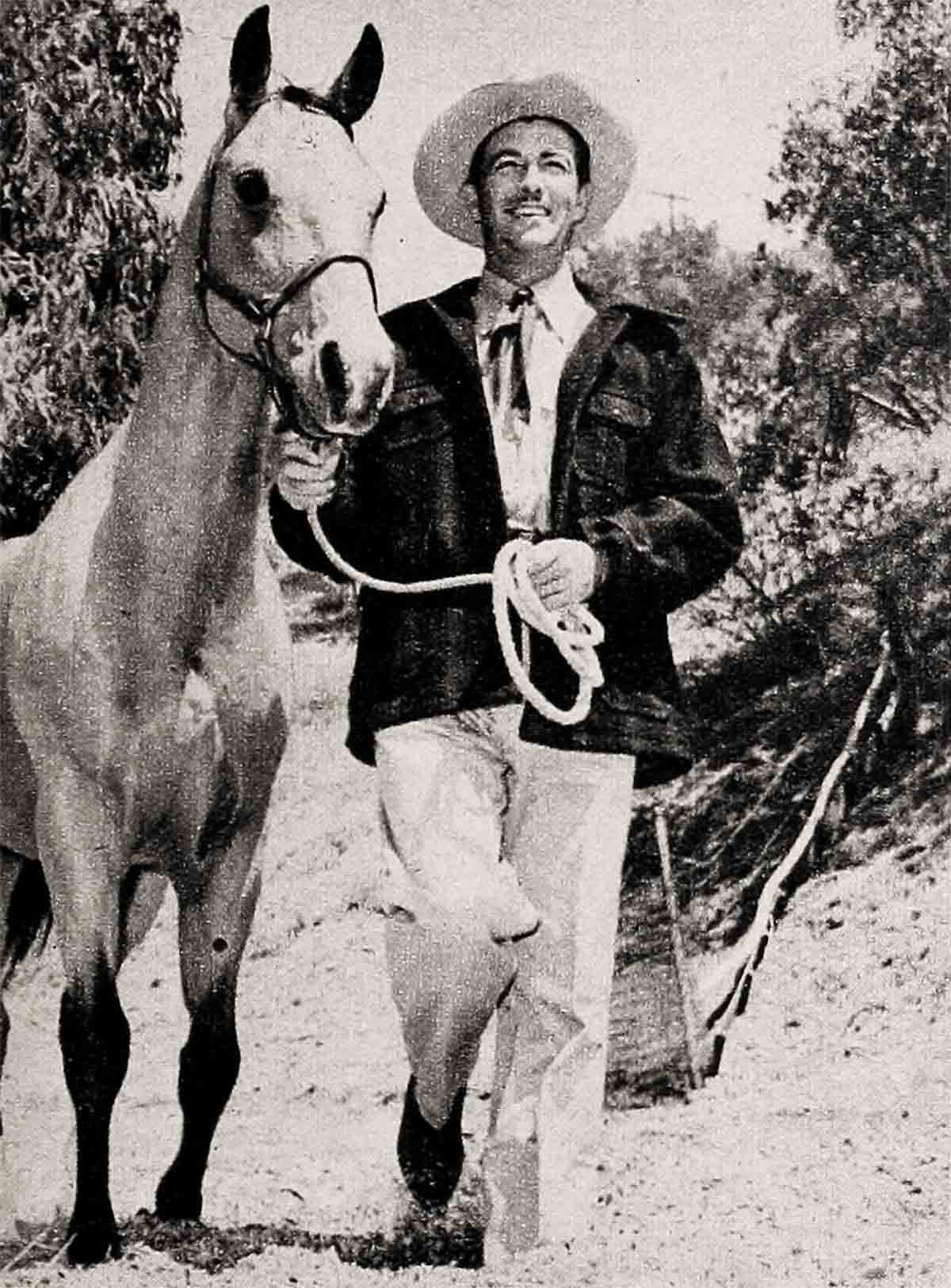

Pomona And The Queen—Robert Taylor & Barbara Stanwyck

“Hey, you!” the usher barked. “Where d’ya think you’re goin’?”

I was slipping into an empty seat beside Robert Taylor and Barbara Stanwyck in a Broadway theater, when a hand roughly grabbed my arm and turned me around.

We hadn’t been able to get these seats together, for the play. But during intermission, Bob had said the one next to them was empty. “Sit here with us, Helen,” he suggested. And that’s what I was starting to do.

“Lemme see ya stubs, lemme see ya stubs!” As I fumbled in my purse quite automatically, I felt hackles rise all around me. Bob was up first, his chin out, his shoulders back. “What’s it to

you, bud?” he gritted. I heard another seat slam back. That was Barbara coming up just as mad. Bob backing me up, Barbara backing him up.

The usher retreated. “Sorry, Mister Taylor. I thought it was maybe a fan botherin’ ya.”

“No fan,” Bob snapped, “and anyway, I like fans, see? And we can take care of ourselves with fans or anybody else.”

“Right,” seconded Barbara, right out loud.

I laughed. I was there, in my capacity as a publicist, to “protect” Bob and Barbara—and here they were protecting me! I’d come to New York and got them involved in a schedule of Manhattan interviews and press appointments when they returned from their European trip last spring, but, as usual with the Taylors, it was hard to tell just who was handling whom. Bob had rustled the theater tickets, filled my room with flowers, grabbed the dinner checks. He’d even given me an osteopathic treatment one hot day when I’d collapsed in their suite!

I should have known what to expect after eight years. It’s impossible to regard “The Queen,” as she’s most frequently called, and “Pomona,” as she calls him, only as clients. Not since a couple of days I’ll always remember.

I’d been handling Barbara’s publicity for about three years. Neither Bob nor Barbara is demonstrative on easy acquaintance; our relationship all that time was strictly business.

One day we were shooting a home layout, and while Barbara was busy making up in her dressing-room, I chatted with her maid and hair-dresser about my recent trip to the East. Just making conversation, I happened to mention an amethyst ring I’d seen in New York and had wanted to buy. I had no idea that Barbara could hear me. I forgot all about it.

Shortly after, I flew again to New York. A cryptic wire awaited me at The Essex House. “If the man from Trabert and Hoeffer’s comes to see you,” it read, “don’t throw him out. Barbara.” I was puzzled—until the man from that jewelry shop did come, and with him a 44-carat amethyst ring, the most beautiful I’d ever seen!

That was a pretty dizzy day for me. You see, it wasn’t only the exquisite gift that threw me—I knew Barbara’s generous habit of presenting golden gifts to those within her small circle of close friends, and my ring meant admission to that circle! I was proud to bursting!

The other day I won’t ever forget was ‘the one before Bob left for Corpus Christi for boot camp. Every photographer in town was at the house to get the only pictures Bob and Barbara had made together since their marriage. When the last one had gone, and Barbara went upstairs, I said goodbye to Bob. “God goes with you I finished, and we shook hands, hard.

“You take care of the Queen,” he said, unsmilingly. I knew I’d been given a trust, and I knew I’d been admitted to Bob’s close circle, too.

It’s not easy to write what I feel about Bob Taylor and Barbara Stanwyck. They are allergic to praise. They usually muffle me with a wisecrack—and both are trigger-quick in that department.

One summer Sunday just after they were married, I got a request for Barbara to do a free broadcast for The Children’s Society. Barbara’s evenings and Sundays are reserved for Bob, but I knew how she loved kids, so I called her. “Sure,” she answered. The day turned out to be a scorcher—hottest of the year. But Miss S. drove all the way from the Northridge ranch to Los Angeles and, after one run-through rehearsal, went on the air and put her audience in tears. Afterwards, I ventured, “You are really wonderful, Barbara, to do this.” She gave me an oblique look.

“Wonderful, hell,” she grinned, “I’m just bribing my way past St. Peter!”

Bob and Barbara are both really shy. Each has a distracting habit of scuttling off when you aim a camera at the other. They never take it for granted that you want them both in publicity pictures. Bob and Barbara figure their acting careers as separate deals entirely.

I was put straight early in our association when I called the house. I recognized Bob’s voice when the phone was answered. “Is Mrs. Taylor in?” I asked. “Miss Stanwyck is in the shower,” he said. “This is Bob Taylor. May I help you?”

I never forgot it.

on with the show . . .

Barbara, of course, came to Hollywood from “show business.” She lives by its creed: the show must go on.

In one of the first pictures she ever made in Hollywood, she and her leading man had to ride horseback. The man drew too fiery a nag and refused to risk it. “We’ll switch,” offered Barbara, “I’ll ride him.” She did, and was thrown and trampled upon. She got up, insisted upon remounting and finishing the day’s work. She worked all that day on pure guts. When the whistle blew, she collapsed. The doctors couldn’t believe she’d been able to walk after that fall. “I had to,” she said simply, “I was too scared to give up.”

The only time Barbara ever actually held up a production was on The Other Love. She had a beaut of a cold, and an outdoor swimming scene. November can be nippy in Hollywood. She swam all day, stayed wet. She had fever and flu that night and it was ten days before she could wobble again. She went to work and insisted she was okay. But it took three months to shake a nasty cough. But do I mention it? I do not. “Lay off my aches and pains,” warns Barbara.

Barbara and Bob would both shrivel me in scorn if I tried to gild the basic facts of their lives. Barbara’s forty. She’s always cracking about it. She has no terror of the several silver threads which have multiplied in her dark red hair. One day at a party, a certain sharp-tongued lady spied them and cooed, “I think your new blonde hair’s so attractive, Barbara.”

“Blonde, my eye!” snorted Miss Stanwyck. “That’s gray.” She asked Bob pronto, “Does it bother you?”

‘Hell, no,” he came back. “I love it.”

“Then that’s how it stays,” she said. And that’s how it is.

My favorite example of the Queen’s back-of-me-hand approach to vanity took place when she made Remember The Night with Director Mitchell Leisen. Mitch is meticulous about feminine glamor and in one scene Barbara wore a very chic hat. Before she stepped into the scene, the wardrobe girl brought the chapeau over and put it on her head.

Stany strode straight to her place before the camera. “Okay,” she said, “let’s get started.”

“My God, Barbara!” gasped Mitch, “aren’t you going to look at yourself in a mirror?”

“What for?” asked Stanwyck. “The front’s in front and the back’s in back. What else can you manage to do with a hat?”

Barbara’s just as frank and unpretentious about any less opulent chapter of her own life. In London, she had her first personal ovation. British lords and ladies, government dignitaries and titled bigwigs saluted her at the world premiere of The Other Love.

I said, “Weren’t you thrilled? Wasn’t it exciting?” Her eyes grew large, remembering. “I looked over that audience,” she said, “and all I could think of was, ‘Well, kid, you’ve certainly come a helluva long way from Brooklyn!’ ”

Barbara was Ruby Stevens, a Brooklyn girl. who rose from poverty to make a name for herself. She’s proud of it. met and bruised against a hostile world plenty, but she fought her way up—telephone operator, salesgirl, chorus girl—to earn recognition.

She hasn’t forgotten. She doesn’t intend to forget.

One day I noticed a new painting hanging in Barbara’s bedroom. It was a seminude by Paul Clemens, a girl slumped in a chair, her feet resting wearily on another chair, her arms hanging heavily at her sides. A dancer in her dressingroom after an exhausting performance. “Nice,” I said. “How did you happen to buy it?”

“Because,” said the Queen simply, “my feet have ached that much!”

Because she knows what it’s like to have-not, Barbara’s heart has a habit of melting like butter. She packet eight pairs of shoes in her bags for wear in Europe; she came back with one, scuffed and beaten. She’d given the rest away the first week in England.

Barbara never tries to duck a “knew-her-when” moment. The honor she’s probably most sentimental about is a bronze plaque with her name on it in Erasmus Hall High School in Brooklyn. Erasmus was Ruby Stevens’ idea of heaven at one stage in her struggling girlhood. She never got there; she had to go to work after the eighth grade. But even though it’s an error, she’s still proud of it. For years she explained carefully that she did not rate it. The name remained. So she relaxed, and enjoys the irony of that plaque, which lists the names of famous Erasmus graduates.

The only person I ever saw Barbara embrace in public was a waiter at the Stork Club. Reason: he was an old pal and benefactor. The Queen is reticent, as I said. When I met Barbara and Bob in New York after their European jaunt, we took in the Stork one night. The first thing Barbara said when we walked in was, “Where’s Spooner?”

I knew about Jack Spooner. He used to be the head-waiter at Billy LaHiff’s Tavern. When Ruby Stevens, and Mae Clarke and Wanda Mansfield, were struggling, often-out-of-jobs chorus girls tackling the Big Street, they got meals on the cuff at Billy LaHiff’s. Now, Spooner worked at the Stork. And in he came, grinning from ear to ear.

Barbara leaned far across our table, threw her arms around him and planted a big kiss.

“Well, Stinky,” cried Jack. “So you’ve been to Europe—see the King and Queen?”

“Not me,” cracked Barbara happily. “When they heard I was coming, they ducked out to Africa!” Everyone in the place was smiling, sharing the delight of their reunion, laughing at the insults the two exchanged so gaily.

shy beneath the skin . . .

Ordinarily, both Bob and Barbara are crisp and taciturn on the surface. It takes a long time before they let you discover the sentiment under that protective crust. When Bob calls me, he still identifies himself: “Helen, Bob Taylor.” First time I ever met Bob, I drove into their ranch in the valley. Halfway up the drive, a man leaped upon my running-board, poked his handsome head in the window and said, “Helen, Bob Taylor.” Just like that. I almost ran into the rose bushes. When I call Barbara and she answers “Yep—” crisply, I make my business short and snappy. But when she says “hello” soft and easy, it’s pretty sure she’ll talk for maybe a couple of hours. The only subject she won’t mention is her own. Generosity.

I remember one day my doorbell rang. I opened it and there was Barbara, her arms sagging with a half-dozen beautiful gowns. She looked as if she’d been caught raiding a bank vault, and glared as she thrust the dresses at me. “Dammit,” she complained, “what are you doing at home? Here—take these.” She whirled and ran back to her car. But pinned on the gowns was a typically Stanwyck note explaining that she couldn’t use the party frocks, and she hoped maybe I could.

She’s that way with all her friends—and Bob. When the Taylors were abroad, Bob, who’s gun and plane happy, took in the continental shooting matches in Belgium. A certain hand-made weapon won the Grand Prix, which means it was at least close to the finest gun in the world. He wanted it. Barbara squawked. “You’ve got enough guns. Take it easy.” But of course, the next day she personally tracked down the gunsmith who’d fashioned the Grand Prix shooter. Bob went out of this world when she gave it to him.

Barbara’s even shyer of planes than she is of shooting irons. If there’s one thing that turns her green, it’s flying. Bob’s a real flyer, and when he begged “Missy,” as he calls her sometimes, and as he named the plane, to let him take her for a ride.

“It’s a long way down,” vetoed Barbara, “and I’ve already seen the view.”

Until, one morning, Barbara pulled another switch. She softly remarked, “I’m flying with you today.” She and Bob hopped off to Palm Springs for lunch, and Bob walked on air for three weeks thereafter. You could tell he was dreaming maybe the Taylors would fly to Europe—maybe, come to think of it, around the world. The Queen cautioned him, after her fashion. “Don’t dream it up too big, Bob.I left my stomach on that mountain bush near Palm Springs.”

Bob Taylor and Barbara Stanwyck both wear wedding rings. They’re sufficient unto one another. They haven’t a wide circle of Hollywood friends; they come close to being a closed corporation. That’s why I appreciate having been admitted so many times to their thoughts. The other night they were outlining plans for another trip abroad at some later day. Barbara said suddenly, Say, what about Helen going along?”

“She’d be a swell dame for a trip like that,” Bob exclaimed. I was thrilled.

two of a kind . . .

Neither Bob nor Barbara likes big Hollywood parties. Each can order a meal for the other without changing an item—shrimp cocktail, rare steak, baked potato, green salad and coffee. Plenty of coffee. Both love horses but both gave up horse ranches when they analyzed the cost sheets. When Bob joined the Navy, Barbara followed him to his stations like any war wife, between jobs. When pictures kept her in Hollywood, she walked strictly alone. They share a consuming interest in their jobs and the industry. They see every movie Hollywood turns out, at their regular Saturday night screenings. It annoys Bob that Barbara’s been nominated for Academy Awards three times and hasn’t an Oscar yet. It doesn’t annoy The Queen. “I just feel like one of Crosby’s horses,” she says.

I couldn’t tell you who has the most devastating sense of humor because it’s a tie. They both like to howl on Saturday night, but it’s a mild form of howling. Just dinner—at La Rue most often—and the screening of two pictures at the studio. Bob likes a Scotch highball; if Barbara drinks at all, it is champagne. Both like to sit on the floor. They prefer to eat buffet style, and they agreed that the first installation in the house they’re planning will be a tennis court. They adore a tiny French poodle, named the inevitable “Missy.” Barbara likes Bob’s moustache, and when she snipped her hair short the other day for B. F.’s Daughter, he raved about it.

The Taylors share, too, what they consider the greatest compliment ever paid them. It didn’t happen in Hollywood but in Paris, where Bob and Barbara went before the London premiére. They’d just left the Arc de Triomphe, when a couple of American sailors trotted past, did a delayed “take” and stared back at those two famous faces.

“Hey,” one said. “You Bob Taylor?”

“That’s right,” smiled Bob.

“You Barbara Stanwyck?”

“Uh, huh,” grinned Barbara.

The gob whirled toward his mate down the street and cupped his hands.

“Hey, Steve!” he yelled as loud as he could. “Americans! Americans!”

THE END

—BY HELEN FERGUSON

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE JANUARY 1948