Mala Powers: “I Prayed . . . And God Heard Me”

Mala Powers sits by her warm fireside, content in the knowledge that her baby son is asleep upstairs in his crib, that her husband will be home from work at any moment. Tree trimmings have been bought; the first exciting packages are carefully hidden away. But she watches the glowing logs, and she hears the grandfather clock chime, and her mind goes back to a dark night only a few years ago, when other presences hovered close to her, bringing terror—and the faith that has made her present life possible.

The gentle firelight, token of home, seems to fade. She is back in the hospital room, waking to the sudden conviction: “This is it. This must be it.”

In Mala’s own words: “I got weaker and weaker, and everything just kind of disappeared all around my body. And I thought, ‘This must be what it feels like to die. I don’t want to die.’ ”

She was alone, but not alone, because she had knelt in the hospital chapel and asked a question—and been given an answer, a silent promise that has now reached complete fulfillment.

Mala’s story of faith begins during another Christmastime, in 1951, when she was invited to join a Hollywood troupe bound for the Korean battlefront. She was undecided. “I knew my mother would worry, but I had an urge to go. I felt somehow that it was important to my whole life that I go.” As usual whenever she had a problem, she prayed for guidance. “I told my mother, ‘If it’s not right for me to go, if God doesn’t want me to go, He’ll stop me some way.’ ”

Nothing happened to prevent her going. One twenty-below-zero night in Korea, she discovered why she was there. Mala, Piper Laurie and Johnny Grant found that the chaplain was going to conduct a midnight service for an artillery unit on the front lines, forty miles from where the troupe was staying. So the three talked the chaplain into taking them along in his jeep, for an unscheduled appearance.

They had been meeting GIs behind the lines, but here was an entirely different audience: men living in a vacuum, knowing that death for them was still within range, even while the truce talks went on. When Mala and Piper led the way into the small tent, there was only silence. “Everywhere else we’d been expected,” Mala says, “but not here. It was just like shock took over. They just sat and stared. The chaplain gave a little service. It all seemed terribly real and terribly unreal at the same time. But the words he said meant so much more in that place. I remember he talked about love.

“An atmosphere of awful loneliness so filled everything that it crept into you, and you felt you were part of whatever the fellows there were experiencing. And you thought, ‘I have a purpose here and a meaning. Human beings belong together. We cannot live without each other.’ I had a sense of really belonging to humanity for the first time. Before that, my world had been myself and my career.”

But in Korea, Mala became ill with a virus infection. By the time the plane reached Honolulu en route to California, she was burning with fever. As soon as she reached home, she went to her doctor, who gave her some capsules of an antibiotic, a “miracle drug” that was saving the lives of many. As far as it was known then, only a very, very few were allergic to it. Mala Powers was one of them.

For months, no deadly symptoms were apparent; her flu kept recurring, and she kept taking the capsules. Then, while she was making a picture at U-I, her condition rapidly became worse. She had violent headaches; she bruised easily and appallingly. Finally, the significant “blood spots” appeared on Mala’s shoulders and neck. When makeup boss Bud Westmore saw them, he promptly summoned a doctor, who ordered her into the hospital, first for a blood test and the next day for transfusions.

“After two or three transfusions,” Mala says, “I felt fine, and I wanted out of the hospital. I had one last scene to do in the picture, and I thought this was all nonsense.” Meantime, a bone-marrow test had been ordered, but Mala had no inkling of the fears that inspired it. “The doctors all looked pretty mopy. ‘When do I get out of here and go back to work?’ I’d ask. ‘Well . . . pretty soon,’ somebody would say.”

Suspicion of the truth came to her in a strange way, before long. She was allowed to leave her room and walk around the hospital, and one restless morning she went into the little chapel upstairs. Mala attends Christ Unity Church, but, she says, “Often if I’m passing a church and it’s open and I have time—it doesn’t matter what denomination it is—I’ll go in. I just like the atmosphere. So the chapel was there, and I went in.”

Only one other person, a lab technician, was there. Mala sat down in front of her, quietly lost in thought. After a moment, the girl came around beside her and said, “Even though you’re not a Catholic, please come into our chapel and pray whenever you want to, because Our Lady will listen to you.” The girl had tears in her eyes. “You’re so young—the important thing is just to stay in the ball game.”

Mala looked at her in astonishment. “What does she expect me to do?” she thought. “Walk out of here and drop dead?” Mala managed to murmur some polite words, but she was so utterly shaken by the girl’s tears and sympathy that she immediately went to a phone and called her mother.

“What’s going on around here?” Mala demanded, then explained what had happened.

“I don’t know,” her mother said.

“I believe you’d better go to the doctors and find out.”

Back in her room, Mala overheard doctors out in the hall discussing some patient. “How old is she?” one voice said.

“Twenty.”

“What a pity!”

These words were a second shock. From walking around the hospital, Mala knew that most of the patients on her floor were elderly cancer cases. She couldn’t think of any other twenty-year-old.

To Mala’s mother, the doctors revealed their prognosis. Among the few cases on record, small children had recovered from this condition, but for adults the fatalities were almost 100%. In their opinion, Mala’s life expectancy was—perhaps—four days.

The valiant mother began searching for words. How could she tell this girl, whose life was dearer to her than her own, that she was going to die? Yet, she says, “Mala and I had always been so straight and so honest with each other.”

“Well, what is it?” Mala asked. “What’s wrong with me? . . . This is my life, and I have a right to know what the doctors say.”

Forcing calm into her voice, in spite of her pounding heart and choked-up throat, Mrs. Powers softened the truth as best she could. “I don’t remember Mother’s exact words,” Mala says. “She didn’t, tell me they didn’t expect me to live over four days, but she made the whole thing very clear. It was a condition they knew very little about, and therefore they didn’t hold out a great deal of hope. But, while doctors were wonderful when you were ill, after all there was only one Doctor—and how could we say anything was impossible with Him?”

Mala was listening to words that held no meaning for her at first. Finally she said, without expression, “Yes.”

She explains, “It doesn’t sink in. You don’t comprehend it. You just can’t feel it. I stayed in this state of shock for a while. It’s like it’s all around you. You feel it out there somewhere. You know it’s there, and you can recognize it with your mind, but you just have to wait until it sinks in.”

Day darkened into night. “Then suddenly it penetrated, and I was frightened! Then I dwelt with it longer, into the next day, until I had a conviction: ‘Not my will but Thine be done’ I got out of bed and I went back to the chapel. It was afternoon—I remember the sun. It was quite warm, and the windows of the chapel were thrown wide open. I remember there was just one shaft of sunlight that came through a window close to the altar. As I was talking, I looked at it.”

No one else was there, and Mala Powers was praying aloud. “I said, ‘If you want me to live, then tell me what You want me to do. If You want me to die, than tell me what You want me to do . . .’ And the answer came—that I was going to live, that I would get well, but that I would have to help. The answer didn’t come in words, as a voice from outside. It was—an experience. Sometimes, when you dream at night, you see a flash of a picture, and in that picture is conveyed a story that might take you fifteen minutes to tell to someone. But in your dream you know what that story is in an instant. It was something like that in the chapel, because it happened in an instant—and yet the whole thing was as clear as if it had been a conversation I had heard spoken word by word. I felt secure and safe and protected, like being cold and then all of a sudden being warm all over.”

The key lies in the words “that I would have to help.” As Mala says now, “I felt if it was just meant for me to die without doing anything—I would have died. I couldn’t have gone through this time just lingering, if I hadn’t had to do something myself.”

Assurance came to her in a flash, but she was not to be healed so quickly. For Mala, there were endless-seeming months ahead, when her faith would be many times severely tried. But she didn’t realize this. After the conversation in the chapel, the doctors marveled at her unshakable belief that she would get well. When they took her blood count each morning, often it was down. Then she would say cheerily, “Don’t worry.” She was encouraging them!

“I just had the feeling that I was already cured,” Mala says. “I was only waiting for the laboratory reports to tell the doctors that I was. And I got impatient with the lab.” But there seemed to be nothing medicine could do to make Mala’s body begin producing blood again. ACTH cortisone was tried, and for a while her count varied up and down. “Then, all of a sudden one day,” she remembers, “It went voom—right to the bottom. And the ACTH never brought it up again.” So this medication was discontinued, and she was given constant blood transfusions, forty in all.

There came blue days. “Even though I knew I was going to get well, nothing in the experience had told me when, and I wanted to go back to work, and I would think, ‘How long?’ And it would seem so slow! I’d always been ridiculously impatient. Now I had to fight it.”

Some days, her heart seemed to beat to one rhythm: when? when? when? On one of these, she went up to the little chapel again, and again she was given an answer, this time wordless, for Mala herself to interpret. “There was a little clock that had a chime with the most beautiful tone. When I walked in, it was chiming five o’clock, and I thought, ‘These are five perfect strokes of time—and I have nothing better to do than just sit here and listen to them.’ ” Before this, Mala had always been thinking, working, trying to drive herself ahead of time. Now she realized how much of life she had missed this way. “It suddenly occurred to me that if God made twenty-four hours in a day, then there’s only twenty-four-hours’ worth he intends to be done, and there’s no sense trying to cram in forty-eight.”

During the weeks to come, Mala found a strange sense of peace in hearing little chimes that seemed to say to her: All good things in time—the right time. She learned the beauty of patience, and she felt again the sensation she had known first on the Korean battlefront: “We are all kind of indivisible—unless we shut ourselves off and build a little box around ourselves.” Through the long nights in a hospital, there are no boxes, no walls thick enough to shut out the cry of a sick child for its mother, the moan of an old man in the next room. Here pain and death were the common enemies, and each human being was kin to the next one.

So Mala was doubly armed on that terrible midnight when she felt that she was dying. She thought she was seized by an internal hemorrhage, the chief danger in her condition. Fear can hurry hemorrhage, she knew. If you panic, your heart pumps faster, and the blood flows more freely. She wanted to shut out fear—but how? Then the soundless, wordless Voice came to her again: “No, no. Let it go. Let it go ahead. Don’t worry. Have no fear.”

Her face glowing with the memory, Mala says, “I believe that I could have died that night, if it had not been for the faith that was given me. And I felt, in a sense, reborn, with spiritual beings everywhere around me.”

She did not have a hemorrhage, and soon she decided that she wanted to go home. She was no better; actually, she was worse. “My blood count was lower than when I’d gone in, but I was sure the hospital had fulfilled its purpose for me.”

Doctors told Mala’s mother frankly that it didn’t matter; she might stay wherever she’d be happiest; they could offer no hope. “They expected a brain hemorrhage—and she would just go,” Mrs. Powers says slowly. Mala was warned that she must go on having transfusions. She must avoid all crowds, since she had no defense against even a common cold. She must avoid falling, for a bruise might start fatal bleeding. She wouldn’t be able to walk even a few yards without being utterly exhausted.

But, one evening unknown to her doctors, Mala was acting again. A friend who produced “The Cisco Kid” on radio had called to ask whether she felt well enough to do a show—and gotten a quick acceptance. Throughout the program, Mrs. Powers sat in the control room praying. “There she was in front of a microphone, with cowboys and Indians all whooping it up and hollering.”

She shouldn’t walk? “But I was taking walks around the block,” Mala says triumphantly, “and going up and down our front steps—we had about fifty of them. I took a lot of minerals with my diet, and I made my own tempo. I did certain things at certain times, as I felt they were right. It was like I was being guided all the time.”

Yet, one unforgettable day, she had a sense of loss and loneliness such as she had never known. “The wonderful spiritual presences I felt all the time began gradually to fade—and disappeared. I was alone. I thought, ‘I’m not in contact any more. I’m doing something wrong.’ ”

In despair, she drove over to see her coach, actor and teacher Michael Chekhov, a man rich in human experience. The wise old man listened and watched as the young girl, crying, told him how she had been deserted. “Pixie,” Chekhov finally said, using his affectionate nickname for her, “how can you sit there and try to dictate to the spiritual world what is best for your own evolution? They came to you and they gave themselves to you. If they now feel that you’re ready to stand on your own, and they wish to depart from you a little bit, and you have to work back up to them—then that’s what’s best for you.”

“That’s true,” Mala said thoughtfully. “They’re still there. I’ll try to work up to them.”

“Remember this, Pixie—no human being is ever given a test at any time that we’re not capable of meeting. Some of us don’t meet it—but we are capable.”

In a faith like Mala’s there was all the strength that she was to need. Disregarding the lab reports, she began to feel better. “I had a little more energy, and my blood count began staying up a little longer between transfusions. At last, in a routine test, my doctors found that my bone marrow was rejuvenating itself. Then they knew I was better—but they didn’t know why. One of them said later, ‘There are just some things that we doctors don’t know.’ ”

In December, Mala was offered a picture, and she told her doctors she wanted to make it. She was going on location in Chicago, and they insisted on giving her three transfusions before she left, to get her blood count up very high.

These were the last transfusions she was ever to have.

By Christmas of 1952—a year since she had been taken ill in Korea—her blood count had doubled, miraculously to everyone but Mala. In a church in Chicago, she prayed to be worthy of the gift of life, and she thanked God for the lifetime of learning contained in that one year.

But there was a gift beyond just living still awaiting her, only two months ahead. She often remembered the sweet chime of the chapel clock: All good things in time—the right time. Now, without any effort on Mala’s part, a light-hearted and happy time was coming. She went house-hunting—and found a husband. A certain young man lost a cigarette lighter—and found a wife.

By February, Mala was feeling well enough that she could take a long look ahead and make plans that had an air of permanence. She and her mother had been living in an apartment; now Mala decided she wanted a house. “One day in February,” she recalls, “I ran into an actor friend who’d been having a difficult time in radio work and had decided to try selling real estate. I told him I’d been thinking about buying a house, and he said if he ran into anything suitable he’d let me know. Shortly after that, he called to say he had a place he thought I might like. Could he pick me up to show it to me? His boss was with him.”

The boss’s name was Monte Vanton. Some people might say this meeting was brought about by mere chance, but Mala has another name for the guiding force.

“Monte told me later,” she recalls fondly, “that when he saw me coming down the steps of my apartment house, it was as if he’d been ‘struck by a bolt of lightning.’ He had admired me as Roxanne in ‘Cyrano,’ but hadn’t remembered my name.”

The first thing I noticed about Monte was his terrific sense of humor. All of us, including my mother, went over to see the house. It was really an odd old place, not at all suitable, and Monte kept making so many funny cracks about it that we were all in near-hysterics before we left. Our little group went to Brown’s then for some hot chocolate, and there Monte offered to find me a home—without charging commission.

“Later, we went to my house, where Monte told us about himself. He had been in the British Merchant Marine during the war, had visited this country and fallen in love with it. After the war, he left England and settled in California. Oh, we talked about lots of other things, and finally he left. Then my mother and I found that he’d forgotten his cigarette lighter. Before this, I’d been telling her I didn’t want any more men in my life. But when my mother, who is very wise, saw the lighter, she said, ‘Mala, you’d better go out with him.’

“The next day Monte called and told me he had another house to show me. This time just the two of us went. It was a house he hadn’t seen before and it was even more unsuitable than the other one, but it was an excuse for us to be together. Monte did something that day that impressed me. The house was on the side of a cliff, and there must have been two hundred steps to the front door. Monte ran up the steps to ask the owner whether we could go through. When she said yes, instead of calling for me to come on up, he ran all the way back down to open the car door for me. I’ve always liked good manners in men, and this made me feel he must be a very considerate person.”

With such a promising start, the romance progressed—but slowly. Five months after their meeting, Monte asked Mala to marry him. “Well,” Mala says, “I didn’t want to get married just then. I knew that some day I would, but I was in no hurry.” True to the philosophy she had learned so painfully, she was willing to wait for the right time, and she knew that the decision would come to her naturally, without worrisome thinking and arguing with herself. And so it did. Monte found her a comfortable, two-story, English-style house off Laurel Canyon in the Valley, just the place for Mala and her mother. Looking back, she analyzes: “I think it was moving into the house and redecorating it that gave me the urge to get married. Every time I looked at wallpaper, my eyes would keep drifting to the nursery paper. It always seemed like the prettiest paper in the store.”

In September, Monte asked her to set a date. “Within the next year,” Mala promised. But a short while later, for no special reason, she decided she wanted to get married right away. When Monte dropped in, she asked, “How would you like to get married eight days from now?”

He said he would, and they were, on October 12, 1954, at Christ Unity Church. “We were too late to send out wedding announcements,” Mala smiles, “so we just called everybody. It was such a rush, we forgot some people we wanted to invite. I’d always said I didn’t want a big wedding, but when it came right down to it, I decided on the wedding gown and all the trimmings. Besides getting ready for this, I was also having wardrobe fittings almost every day on a picture I was to make. But I’m not sorry for my decision. Even thought it was hectic, it was a beautiful wedding, and we had a reception at my house for over a hundred people.”

Now, for once, timing seemed to be wrong. Four days after her marriage, Mala was shipped off to Sonora on location. But Monte came up to join her. “It turned out to be a perfect honeymoon,” Mala says softly. “We had a lovely guest cottage to live in, with a brook that ran right by our front door. And in the morning deer would be jumping over the fence. We were there almost three weeks, and during that time I worked only three days. We went fishing and cave-exploring. If we’d had a chance to plan our honeymoon, it couldn’t have been more perfect.”

In the same way, their hopes for starting a family immediately fulfilled not according to their own plan—but still at the right time. This past year, Mala had four pictures ready for release: “Tammy and the Bachelor,” “Man from Abilene,” “Death in Small Doses,” and “Unknown Terror.” She was finishing a fifth, “Man on the Prowl,” when she made the announcement that she was expecting a baby—in three months! “I was so small,” Mala explains, “that I was able to keep working in pictures up until my sixth month. Everyone was surprised.”

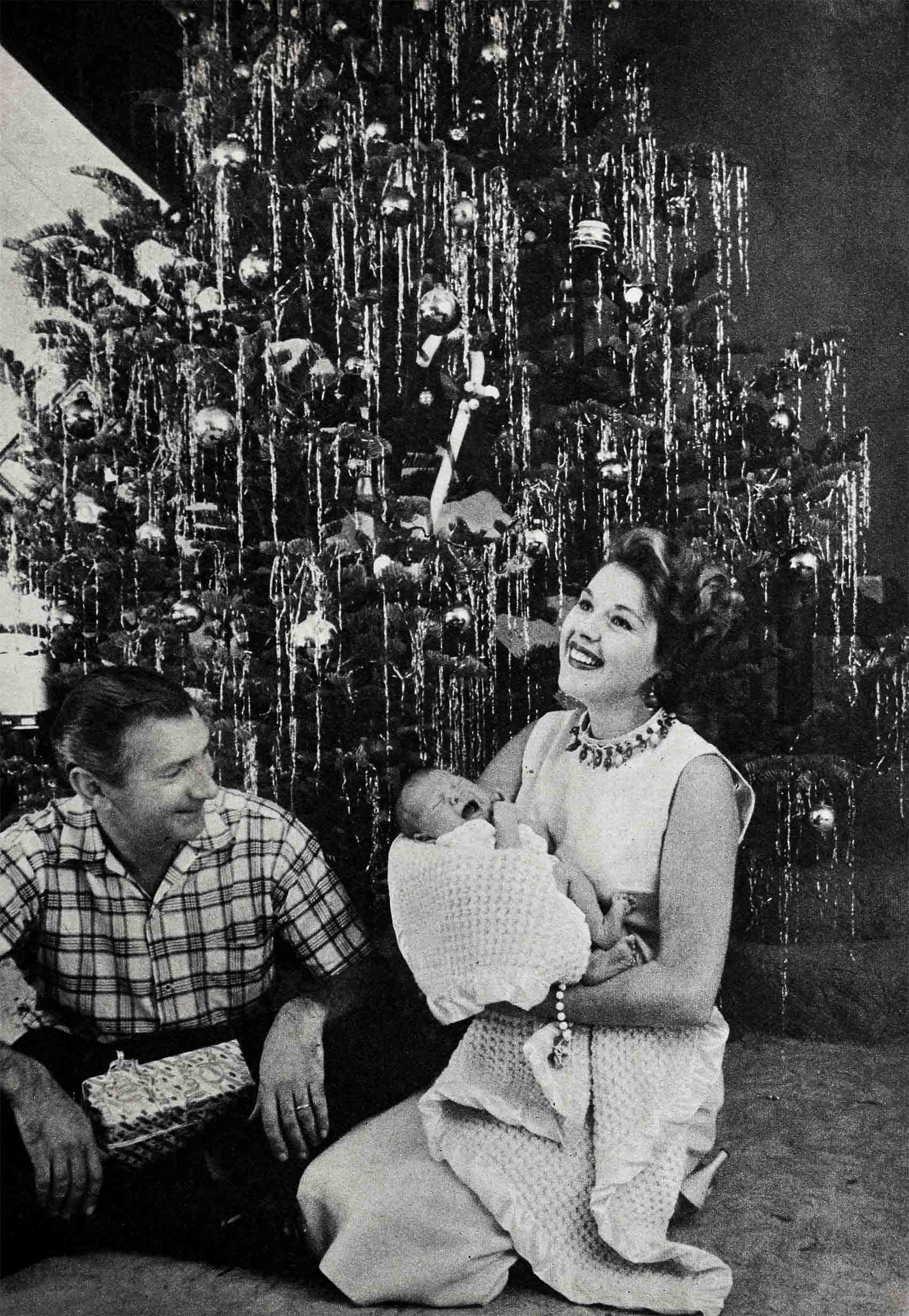

As you might guess, Mala made preparations for a “natural” childbirth, with exercises and—more important—a relaxed frame of mind. “I had no fear whatsoever,” she says earnestly. “I really looked forward to it. Although I wasn’t able to completely fulfill the ‘natural’ childbirth ideal, I’m grateful for all the time that I was conscious. I think it was rougher on my doctor than it was on me. I was so happy to be having a baby that I hardly felt the pain. And it didn’t matter to me whether it was a girl or a boy. When it turned out to be a boy, we named him Toren Michael. We call him Tory for short. The Michael is for my teacher, Michael Chekhov, who gave me so much encouragement when I was ill. The Toren is just a name that popped into my mind from out of nowhere. I’m not even sure that there is such a name, but we love it. And we hope to have at least two more children.”

Here is a girl who not so long ago was delighted to be able to walk around the block, to go up a flight of steps. Now she has given birth to a child; she nurses him; while she was pregnant she did all her own housework for two months; she takes a singing lesson daily, exercise classes three times a week, dancing lessons three or four times a week—and relaxes with horseback-riding!

In the home that Monte found for her, the home they share, Mala comes out of her dream by the firelight. She hears the front door open, and she hears her husband’s voice. But in her heart she will always hear the chime of the chapel clock at the hospital—now a cherished reminder. All good things in time—the right time.

THE END

—BY MAXINE ARNOLD

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE JANUARY 1958

No Comments