Sophia Loren’s Own Story

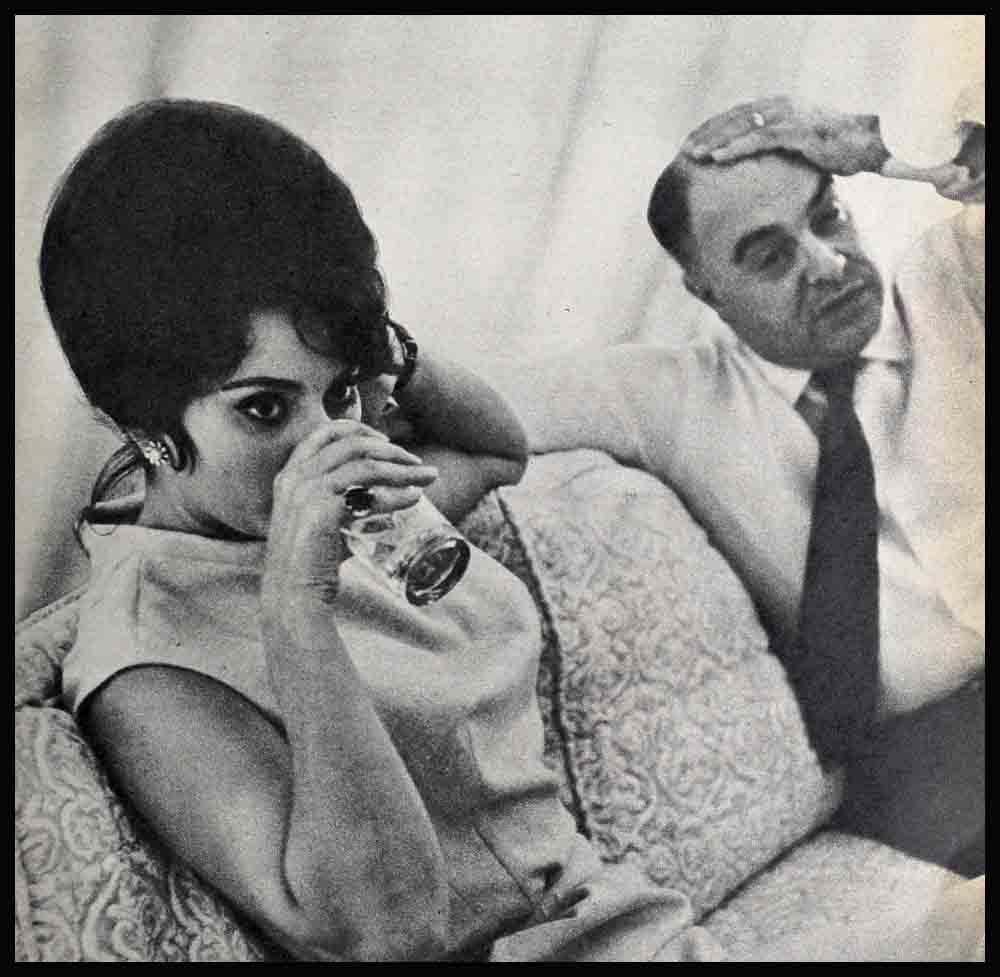

This is a report on how Sophia Loren is now forced by State, Church and Society to live with a married man. That man is Carlo Ponti, whom she has considered her husband for several years now, ever since their Mexican marriage-by-proxy. When bigamy charges were brought against them in Rome recently, they made the sad decision that the only solution was to annul their marriage. They looked on it as the first step, legally, toward a marriage that would be recognized as valid. In the meantime, their lives are terribly complicated by the fact that since Church, State and Society recognize Carlo’s separation from his first wife, Giuliana Fiastri, but not his divorce, he is considered to be still married to her. And Sophia, by continuing to live with her “husband, ” is technically a party to adultery and he, technically, an adulterer. Nevertheless, they seem determined to proceed with their plan to adopt a child. In Europe it would be possible—morally condemned, perhaps, but legally possible. Here, then, is an intimate account of Sophia’s feelings, based on interviews held just before and after her marriage to Ponti was finally dissolved.

INTERVIEWER (interrupting Miss Loren on the set of “The Condemned of Altona,” the film she and Ponti were making at the Italian seacoast town of Tirrenia): “Judge Carlos Uranga Munoz has just ruled in Mexico that the lawyers who stood in for you and Mr. Ponti at your proxy wedding ceremony in Ciudad Juarez did not have the proper power of attorney, and that, therefore, the court ‘does not recognize the existence of the marriage ceremony.’ How do you feel about the annulment? Does it make you feel happy or sad, Miss Loren?”

SOPHIA: “It’s the most wonderful news I ever received—more wonderful than the announcement that I won an Oscar.”

INTERVIEWER: “You lived with Carlo as man and wife until the annulment; do you consider that relationship as though you committed a sin as you look back on it now?”

SOPHIA: “Sin? It is such a harsh word. What does it mean? They say—I don’t hear anyone say it to me but I just read about it—that I have lived in sin. It is so ridiculous. We were married so we could be man and wife to live with our heads high in the eyes of everyone, even the prudes. Could we have just lived together without marriage? Then nobody would have bothered us. It is done every day, here and everywhere in the world. If they put people in jail for that kind of sin, then we will need to do nothing but build more jails to hold all the people who sin.”

INTERVIEWER: “What were your feelings when you finally decided to have your marriage to Carlo annulled?”

SOPHIA: “I worried and cried so much about the situation between Carlo and me that, when we finally made the decision to annul our Mexican marriage, I had no tears left.”

. . . “No tears left.” She had cried when the actual proxy took place in Mexico. Carlo was off somewhere in Europe, she was alone in Hollywood, and down there below the border. in a town she’d never visited, in front of a judge she’d never seen, two lawyers she’d never met were mouthing sacred vows that would join Carlo and her in holy matrimony.

Sacred vows. More accurate would be “legal mumbo-jumbo.” Mumbo-jumbo because she didn’t understand why she and Carlo couldn’t be married in church—a church like the Church of the Madonna deI Carmine to which, when she was a child back in Pozzuoli, she had gone faithfully to Mass every Sunday. After all, his wife had given him his freedom (also in Mexico—a proxy divorce.)

She had cried later also when Church, State and Society joined in declaring her marriage to Carlo “bigamous” because Italy does not recognize divorce. Cried because she loved Carlo and loved her church and her country, too. She said, “It’s impossible to change the law of the Church which is based on the sacraments,” but, almost in the next breath, she added, “Carlo is my life. I cannot imagine myself ever to be without him. Carlo satisfies me in every way. When we are apart, I hurt—really hurt physically.”

INTERVIEWER: “After everything that’s happened—the bigamy charges, the annulment and all the rest—do you still believe that you and Carlo will ever be allowed to get married?”

SOPHIA: “That is our dream, that somehow we can marry with the blessing of the Church and live in Italy. Our dream.”

INTERVIEWER: “Do you blame Carlo’s wife for the bigamy charge brought against you?”

SOPHIA: “I cannot say I do. I understand she and Carlo parted with understanding and on friendly terms. Someone else brought the charges against us. No, I have no hard feelings toward her because in my eyes, and in Carlo’s she is no longer his wife. I am.

“If it had been Carlo’s first wife who had lodged the complaint about us, it would have been understandable, but it was not.

“I was sued by a woman whose husband had left her. Anyone can bring a charge of bigamy against another person in Italy. This woman didn’t know me but she was miserable and bitter and she said, ‘I want to make every woman suffer.’ If it is any satisfaction to her. I have suffered.”

INTERVIEWER: “The name of the woman who sued you was Mrs. Brambilla. Just who was Mrs. Brambilla and how did she become involved in your affairs?”

SOPHIA: “Who knows? She made the charge in the name of some association. I think it was some association for the protection of the family.”

INTERVIEWER: “Doesn’t it seem ironic that of all people you, who have longed all your life for a real family, should be denounced as a bigamist and, in short, be prevented from making a family of your own?”

SOPHIA: “Ironic, yes. But a better word for it would be rotten.”

INTERVIEWER: “Speaking of a family, you said you wanted a baby. Does what happened—the recent annulment of your marriage to Carlo—change your plans?”

SOPHIA: “Not at all. I want marriage, a home and children. And I want these things with Carlo, together. My desires are like those of many, many women in Italy and all over the world. In time we will have these things.”

. . . “In time.” She’d once said, “We’d love to have a baby. But we don’t pick the time. Only God can pick the time,” but man and made-man institutions persisted in interposing themselves between God and herself and insisting, in the name of God, that she not have a child, until she cried out to one reporter, “They won’t let me have a baby. And I won’t be a complete woman till I do.”

When asked about how many children she wanted, she replied, “Five of them. And I would like to spend all my time being a wife.”

But she had no child of her own.

On another occasion she confessed, “l would like to have triplets. But there are not even twins in my family or Carlo’s.”

But she had no child of her own.

Once she explained, “I have mothered my sister and mothered my mother.” And, about Carlo, she said, “Sometimes I am a mother to him, too.” When she heard that her sister, Maria Mussolini, was expecting, she commented wistfully, “Brava, and hurry up so J that I may take this baby for myself.” The child came, and Sophia, the doting aunt. cooed at and cuddled and dangled and diapered the infant.

But she had no child of her own.

It was shortly after the charge of bigamy was brought against Carlo and herself that she returned to Italy to face the court, even though it might mean a jail sentence of five years. But she stood before her accusers with calmness and dignity. She had to clear her name, to unravel the tangle of her marriage. Now she had another reason—more important than silencing gossiping tongues: she was expecting a baby.

Shortly afterwards, however, her physician told her a mistake has been made. She was not pregnant.

But perhaps, perhaps, there was another way. Adoption. Just before her annulment ıvas granted, Sophia spoke about this to a reporter. “There was a train crash in Italy ] not long ago, and a little boy was orphaned.” she said. “I hoped to adopt him, but at the last moment they found he had an aunt. I was very sad.”

But she had no child of her own.

No child, but also no time to wait through the months and the years until someone, I somewhere, might officially declare: Now, at last, you and Carlo can have a child.

So almost at the moment when Carlo and Sophia’s marriage was annulled, columnist Sheilah Gruham announced, “Sophia Loren and Carlo Ponti plan to adopt a baby. Having one of their own is getting more and more impossible, what with the annulment of their Mexican marriage. They have no plans to live apart . . .”

Sophia, in effect, was saying. “We’re not married, but we’re adopting a baby.”

INTERVIEWER: “Your mother, according to what you’ve said in the past, never was married.”

SOPHIA: “It’s true, but it made no difference to them. In some ways, I suppose, it made my mother unhappy. It made me unhappy also, when I was old enough to realize it. But it was the way Fate wanted it. I am not ashamed of my mother’s and father’s relationship. I would not be ever ashamed of two people who live as man and wife when they are deeply and unalterably in love with each other.”

INTERVIEWER: “Like Carlo and you?”

SOPHIA: “Like Carlo and me.”

. . . “Like Carlo and me.” From the beginning, when she was in her early teens, it had been only “Carlo and me, me and Carlo.” When they’d taunted her for going with an older man, tears filled her eyes and she’d answered, “Why don t you try to see him with my eyes, the way I see him. You don’t understand; you’ll never understand.” It was simple. She was head-over-heels, yesterday—today—tomorrow—then—now— forever in love. “We are always on a honeymoon,” she’d said proudly. ” W e don t need a location to be on a honeymoon. H e are happy everywhere. We are good together.

INTERVIEWER: “If Carlo cannot get his divorce from his first wife, would you go to another country with him?’’

SOPHIA: “I hate to think of that. I want to believe he will get the divorce and that we will get married. I do not want to go through what has already happened again. But if new obstacles should be put in our way, then we may not have a choice but to do that—to go off somewhere. We are too much in love to be separated by a legal maneuver that is against all reason. against human nature.”

INTERVIEWER: “Would you have any regrets if you have to leave your native Italy to live with Carlo someplace else?”

SOPHIA: “Of course I would feel terrible if I had to give up my citizenship, but I would rather do that than go through life with this yoke they have put around my neck. The world is a big place, and Carlo and I can find happiness anywhere. But I have not lost faith in Italiaıı law. It is my country here, and I know something will work out. God willing.”

INTERVIEWER: “Would you live in America?”

SOPHIA: “I have a great feeling for America. I know Carlo and I would find happiness in America if we came to live there. But I know we will feel happy in Italy once this legal problem is settled once and for all. I get letters every day from Italians who are on my side. They understand and sympathize with my problem. I am fighting for a popular cause. it would seem. Love.”

INTERVIEWER: “If you and Carlo. for any reason. could not marry again, would you still stay with him?”

SOPHIA: “I have known Carlo since I was a little girl, maybe fourteen. I was skinny and not pretty. He was the first real person I’ve ever known. The only man I have ever loved. I come from that kind of family. We pick a man and love him until death. There is no other way for us. My sister and mother are like that, and I am, too.”

. . . There was only one more question to be asked. Not to Sophia, but to Carlo Ponti, the man who was accused of being a “bigamist” for staying with the woman he loved (despite the annulment, the bigamy charge has not been dropped) and who will be labeled an “adulterer” if he remains with her; the man with whom, despite the fact they’re not man and wife, she reportedly is planning to adopt a child. . . .

INTERVIEYVER: “Now that Sophia and you are no longer married, will you move out?”

CARLO: (glares at the questioner, looks lovingly at Sophia, and then blurts out) : “Do you think I’m crazy?”

—JlM WILLIAMS

Sophia is in “Boccaccio ’70” and will be seen in “Madame,” both films Embassy.

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE JANUARY 1963