If You Were Betty Hutton’s House Guest

If you were a house guest of Betty Hutton you’d be the house guest of the giddiest and gayest human jumping bean in Holly wood. You’d be deafened, dazed and dazzled by the uproar—and delighted!

Your first mental upset would come when you pointed your car toward the Hollywood hills and began a devious climb up a snakelike road that led you higher and higher until you finally reached what looks like a tiny one-story tan stucco house with a “roll” roof. The tiny house is an optical lie, you shortly discover, for it really sprawls backward down a steep hillside for three stories.

AUDIO BOOK

You’d park your car in a neighbor’s flower bed to keep it from careening down the hilly road, walk past the garage doors and open a small gate that leads into the handkerchief-sized front garden—and in ten steps you’d be at the front door.

Twilight is falling, and in the clear evening air you can hear the neighbors’ dinner noises floating from one side of the canyon to the other. But now the door opens and a pretty colored maid named Mary invites you inside. ‘I’ll get Mrs. Hutton—Miss Betty isn’t home from the studio yet,” she says, ushering you through a small hallway—into an entrancing living room. It’s your first warning that the outside of the house belies the inside; for you find yourself in a big, square, gracious room entirely done in elaborate French decoration . . . and the comer made by the two farthest walls is lined with windows overlooking all of the twinkling lights of Hollywood and the nearby hills, encrusted with white houses.

After the lovely view, your eye is attracted back to the room. Its floor is covered in pale green figured carpeting, and while you wait for Betty’s mother to appear, you notice that the walls are tinted to match the rug, the drapes on the many windows are green with a gold rose pattern and the furniture is heavy gilt, upholstered in rich gold or green brocades. A dainty marble fireplace is opposite the windowed vista, with a section of modern glass outlining it. There are two couches and at least ten easy chairs scattered around the room—and under an ornate gold-framed mirror stands a console spinette. On either side of the fireplace are low built-in bookcases, sparsely sprinkled with books. This room is shiningly neat, formal and yet comfortable; and you’ve already noted that Betty doesn’t believe in family portraits . . . there isn’t a picture in the room except for some formal French water colors on the walls.

But now you hear Betty’s mother coming up a flight of stairs from somewhere below in this hillside house, and you turn to greet her. Her name is Mabel Hutton, but she’s known to you from this moment as “Mom,” and you love her at once. She’s a thin, energetic, young-looking woman with bobbed ash-blonde hair that’s flying around her ears, alert green-gray eyes and a sweet face. She’s wearing pastel-green slacks and a blouse, and swinging from one hand is her four-year-old blond grandson, John Thomas Philbin III—who is Marian Hutton’s son, and Betty’s beloved nephew. (John lives at his bombshell aunt’s house as much as at his own traveling family’s.) Mom and he settle on the sofa together, while Mom tells you how she located this house last November on the very day Betty got back from her South Pacific entertainment tour, and how they rent it furnished, and how much Betty loves it.

Right here Betty herself arrives— you can hear her (and so can the neighbors) for minutes before she appears. There are five blasts on a horn outside, the sound of Betty’s blue convertible Buick sedan shrieking to a stop in the garage, and then the front door bursts open and Betty has leaped inside—all flying blonde curls, dancing hazel eyes, a flapping yellow sports coat over a yellow sweater and skirt. Her feet are in sandals and yellow bobby socks, and she literally broad jumps across the room to you, yelling “Hiya, doll-face!!” Then she envelopes you, Johnny and Mom in successive bear-hugs. Within two seconds she has seized your heavy suitcases and is rushing them and you down the green-carpeted hallway. Behind you, you can hear Mom herding little Johnny downstairs for his supper.

Meanwhile, Betty is blithely informing you that except for the living room, this top floor is all her domain. To the left, off the hail, is your bedroom—a trim, square, small room with the same green carpeting as the living room and hall. The double bed has ivory satin for a spread and the same satin repeated in the quilted headboard. The walls are pale ivory-yellow, there are yellow drapes and a fluffy dressing-table in white with pink trimming. There are also a couple of easy chairs in pale green . . . but now Betty, having tossed your suitcases in a corner, is dragging you down the hall again to see her suite. “First time I’ve been living like a movie queen, and I’m eating it up!’’ she says in her gay, happy voice.

Her bedroom is something like your own, only a little bigger in size. Her rug is aqua blue, her walls a paler blue and her bed covered in a quilted ivory satin spread with a matching quilted headboard. The wall behind it is draped in the same satin, with two dark rose panels on either side. There’s also a blue easy chair with a blue baby pillow in it, and a pink chaise longue with a pink baby pillow on it. And a glass-topped dressing table in the palest pink net skirt whose top is jammed with perfume bottles—at least two dozen of them. But what really charms you is a stuffed Bambi deer, standing among the pale yellow and rose window drapes, staring soulfully at you.

“A wonderful priest, Father Sullivan from Newark, New Jersey, gave that to me,” Betty tells you, “because I took him on the set of ‘Going My Way.’ ” Later you realize that there are toy animals all over the house—they’re Betty’s one obsession—and the three books on the table beside the chaise longue are your first introduction to her versatile reading habits.

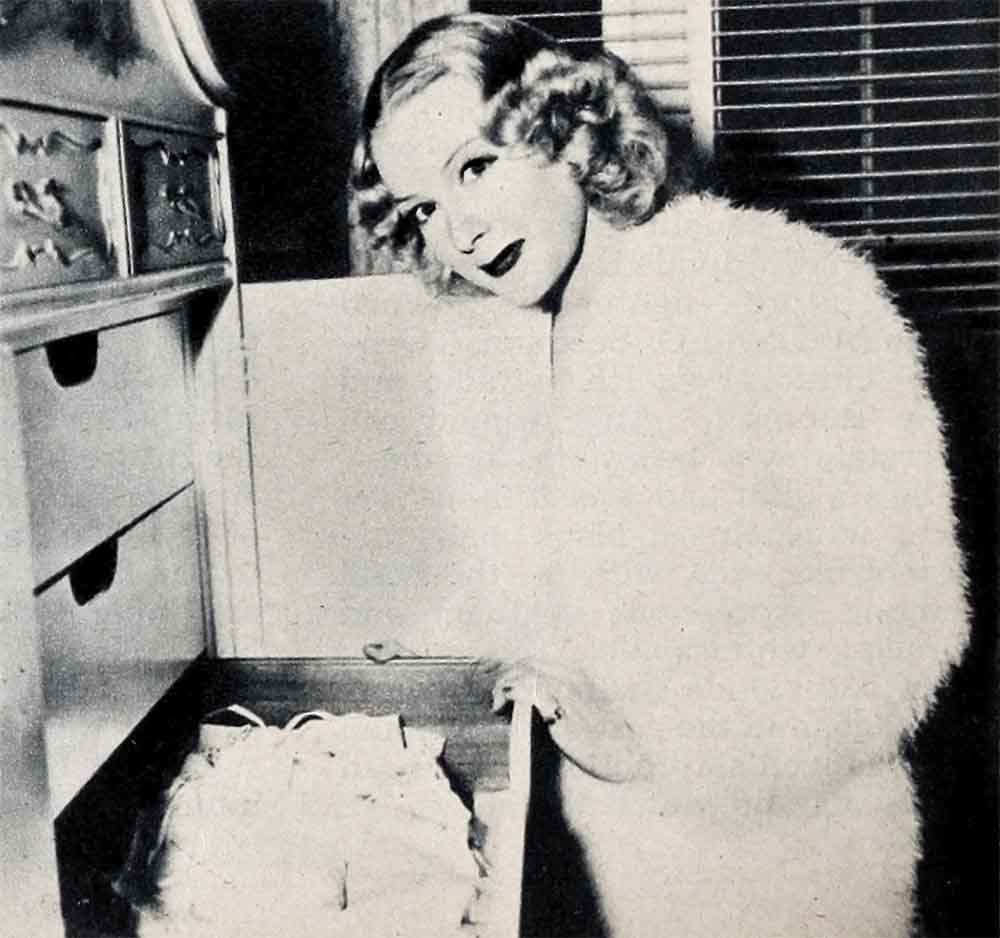

Next thing you know she has you peering into a closet where you see several pairs of high-heeled mules, six bed-jackets and quilted bathrobes and lounging pajama sets. On a shelf above are four cellophane boxes neatly packed with gay feathers for Betty’s hair.

Down the hail again, past her white and red bathroom with its towel racks crowded with big fluffy white towels marked “BJH.” (The J is for June.) Then she triumphantly heaves you into what looks like a giant closet. “Here are the rest of my clothes,” she announces. One complete wall is filled with two clothes-racks sagging under the weight of Betty’s many sport coats, sport dresses, date dresses. Against another wall stands Betty’s practical dressing table, the one she uses daily. It too is packed solid with perfume bottles, and its drawers, as Betty zips them open and shut for your benefit, show you neatness beyond a scientist’s dreams.

One drawer contains nothing but her stockings; the next nothing but her bobby socks (six pairs of them labeled “Betty” in red embroidery—Christmas gifts from her mother); the next two hold her collection of costume jewelry. There’s a chest of drawers with her gloves, belts, slips, underthings, handkerchiefs, purses, hair-scarves, hair ribbons and bows and hair flowers each in place. But you still haven’t seen the closet of this ex-bedroom. Here are Betty’s blouses and skirts, by the dozen. You notice though that shoes are noticeably lacking in the Hutton household. Betty took ten pairs with her on her Central Pacific tour, and the only ones that were able to stand the wear, tear and weather were the pair of G.I.’s presented to her by the Army. She is in the process of making application at her local ration board for two shoe stamps to get her through her latest picture.

At last, then, you’ve seen her whole wardrobe. So you go into your room and begin to unpack. But you’ve barely lifted the lid of your suitcase before Betty the human cannonball is back again.

Now she’s dressed in black mules and a stunning pair of black Chinese lounging pajamas, with the square box coat topped by a white embroidered collar—she brought the outfit back from Honolulu after her eight-week trip through the South Pacific. “Across the hall—march!” she orders, and you find yourself in a tiny sunroom-bar with one wall almost entirely windows overlooking the canyon and surrounding hills. She’s already behind the little white leather bar mixing up something; and meanwhile you notice the black-and-white-checked linoleum floor that looks like marble tiling, and the glass-topped table and white iron chairs. You’re barely settled in one, when Mom calls from somewhere below, “Dinner’s ready!” and Betty leads you down from this floor to the one below.

On this second floor down are the dining room, breakfast room, kitchen, Mary’s pleasant bath and bedroom—and a private wing holding Mom’s big bedroom and bath. (There is more to come, still another floor down, but so far you’re in blissful ignorance of that.) The green-carpeted long flight of stairs downward deposits you smack in the dining room, which is the least eye-stopping room in the house. It’s just a nice dining room, with a walnut dining table under a small crystal chandelier. Standing on the green rug, against the tan-striped wallpaper, are tan upholstered chairs; and the drapes are in ivory with a tan floral print. Here you, Mom and Betty are served a delicious dinner by Mary and you notice that Betty is not eating very much. “Gotta diet,” she says, “because yesterday I slipped up.”

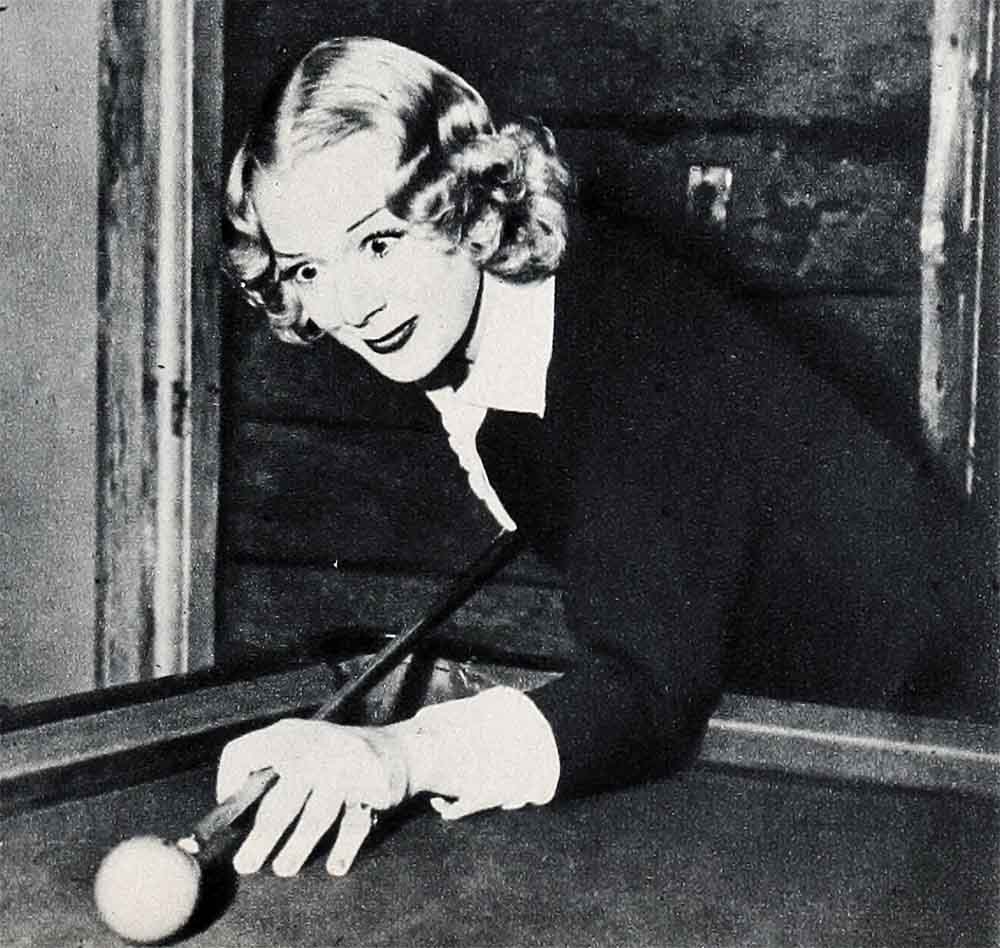

Her best friends are four, and they drop in as if by signal the minute dinner is over . . . Lindsay Durand of the Paramount publicity department, Eunice MacFarlane (Betty’s pretty hairdresser), her husband Hank MacFarlane who works at Republic Studios, and Jimmy O’Toole of the Universal publicity department. These four are closest to Betty’s heart, and at sight of them she whoops hellos and you find yourself being escorted down another flight of stairs to the playroom, three stories down the hillside.

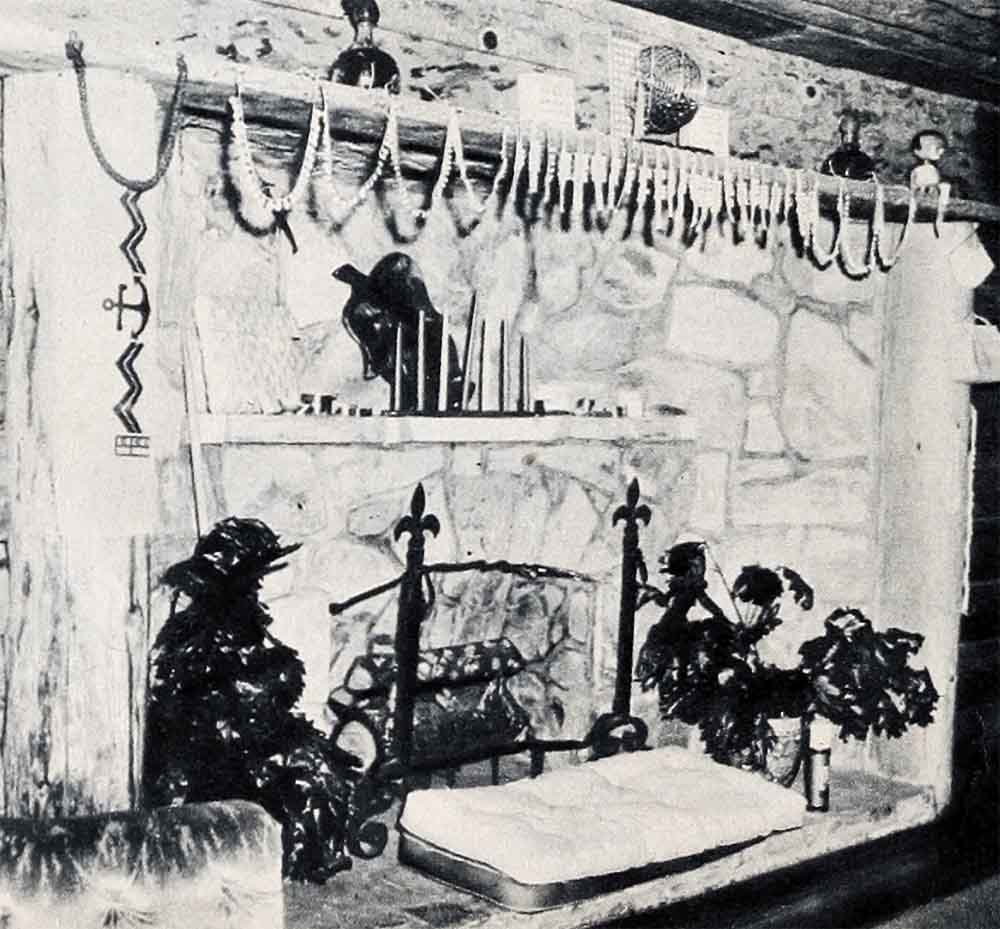

You can’t help gasping in sheer pleasure at sight of it. It’s everything a playroom should be. It has log-cabin walls and it looks like four low-ceilinged rooms in one—making a long, irregularly-shaped play-spot. One “room”-section has a Ping-pong table in it; another has a billiard table; a third has a card table, a blue couch and some easy chairs set on a rose rag rug—but the middle section is the one to which you all head instinctively. It has a huge natural rock fireplace with a wide rock ledge to sit on and blue velvet easy chairs grouped comfortably around it on a blue rag rug. A small bar faces the fireplace, and a big radio . . . and arranged around the mantel are Betty’s trophies from her trip into the South Pacific, which she immediately and enthusiastically begins showing you.

She has everything, from a bleached Jap skull with a lot of Yankee names scrawled on it in ink to Japanese prayer books; a Banzai (or Japanese death) flag; dozens of shell necklaces from South Sea natives; a hari-kiri knife; one American general’s complete decorations—and a beautiful rosewood cheese tray shaped like three big hollow leaves, which Betty carted back from Honolulu as a present for her mother.

Then Betty tells you what happened in the South Pacific to her complete wardrobe of Edith Head-designed clothes—they rotted and moulded away in three weeks of the moist tropical weather. Threadbare, she flew to Honolulu for a new wardrobe, and then headed back to the G.I.s in the remote islands—only to have wardrobe number two destroyed also. In order to have something to fly back to Hollywood in, she had to shop once again in Honolulu, coming home with a couple of suits and two pairs of lounging pajamas. Meanwhile she had lost $2,000 worth of clothes in two months. The result? She’s going right back to repeat her tour the minute her current picture, “Too Good To Be True” is finished.

She also tells of the powder room problems on Saipan—how every time she and the pretty dancer Virginia Carroll were faced with bathroom necessities, thirty soldiers had to escort them through the sniper-ridden trees to the improvised bathrooms. Then the men formed a discreet circle around the girls, with backs turned, and stood guard until the girls called to them—then the thirty men closed in on them again and marched them solemnly back to camp, in formation!

But suddenly it’s eleven o’clock, and the guests file through the silver-walled powder room off the playroom—and to an enormous cement storage room. Here is an electric stove, a refrigerator and shelves full of food and dishes . . . and in no time Betty has whipped together a pot of coffee, some scrambled eggs, and toast. After the late snack, the guests go home; and you and Betty yawn your way upstairs, turning off lights as you go, and head for your own rooms.

The next day Betty doesn’t have to report to the studio and long before you have awakened she has had her breakfast in bed on a tray, and has diligently read the Los Angeles Times, the Examiner and the Hollywood Reporter. Then she has taken her first shower of the day (she takes four, usually), and climbed into slacks and a shirt. Finally, it’s ten o’clock and you are still serenely asleep—when you are almost knocked out of bed by a blast of sound. As you plunge in bewilderment to the middle of the floor, it dawns on you that the Blonde Bombshell is practicing a song in the living room. You can also hear the tinkle of the spinette keys—Joe Lilley, music arranger for Paramount and the Hutton arranger par excellence, is playing to her singing.

Afraid you’ll miss something, you hurry getting showered and dressed, and you wind up in the living room watching Betty’s roof-shaking performance for an hour . . . side-by-side with her entranced little nephew Johnny.

You have breakfast. The minute you’ve set down your empty coffee cup, Betty starts rushing you through one of her dizzying days—dashing about town with her, horseback riding—any number of things. By nighttime, when you’re ready to beg for peace and quiet, Betty is still shooting on six. Though you may go out you usually end up staying at Betty’s with the same foursome joining you.

By another day you know the story of Betty’s climb to fame from poverty as a child in Lansing, Michigan, when Mom worked hard upholstering furniture to support her two daughters. You know that Betty began singing publicly when she was twelve, and that she sang progressively for Vincent Lopez’s band, for the Casa Manana night club in New York, in vaudeville and in Broadway shows before hitting Hollywood. You know that for many months at a time she owned only one cotton blouse and skirt, which she washed and ironed every night in her boardinghouse room so that they’d be fresh for the next night’s show. You know that years of a starved love for loveliness have made her clothes-mad now—and you know that somehow all that energy demands nine hours’ sleep a night, and gets it!

You know that she doesn’t own a hat, and that she came to Hollywood four years ago dressed like a boudoir doll in ruffles and bows—and that since then she’s become one of the smartest dressers in Hollywood. You know that she favors black, and all shades of pastel. You know that she’s one of the most famous girls of twenty-three in the world today; that she’s five feet four inches tall, that she weighs 112 pounds, and that she has toy pandas, dolls, dogs and horses all over the house in various rooms—beginning with the time Lou Costello gave her a toy monkey years ago in New York. You know that she reads every best-seller going, that she drinks milk all day long, that she’s very proud of having been chosen “The Most Cooperative Actress of the Year” by the Hollywood Women’s Press Club.

And you know—as if you didn’t know it by just watching her on the screen—that she can’t sit still a moment, unless it’s with a good book. You know that wherever Betty is there is noise, excitement and confusion . . . and that you loved every minute of your visit with her. Why, the minute you’re rested up again you’ll be back for more!

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE APRIL 1945

AUDIO BOOK