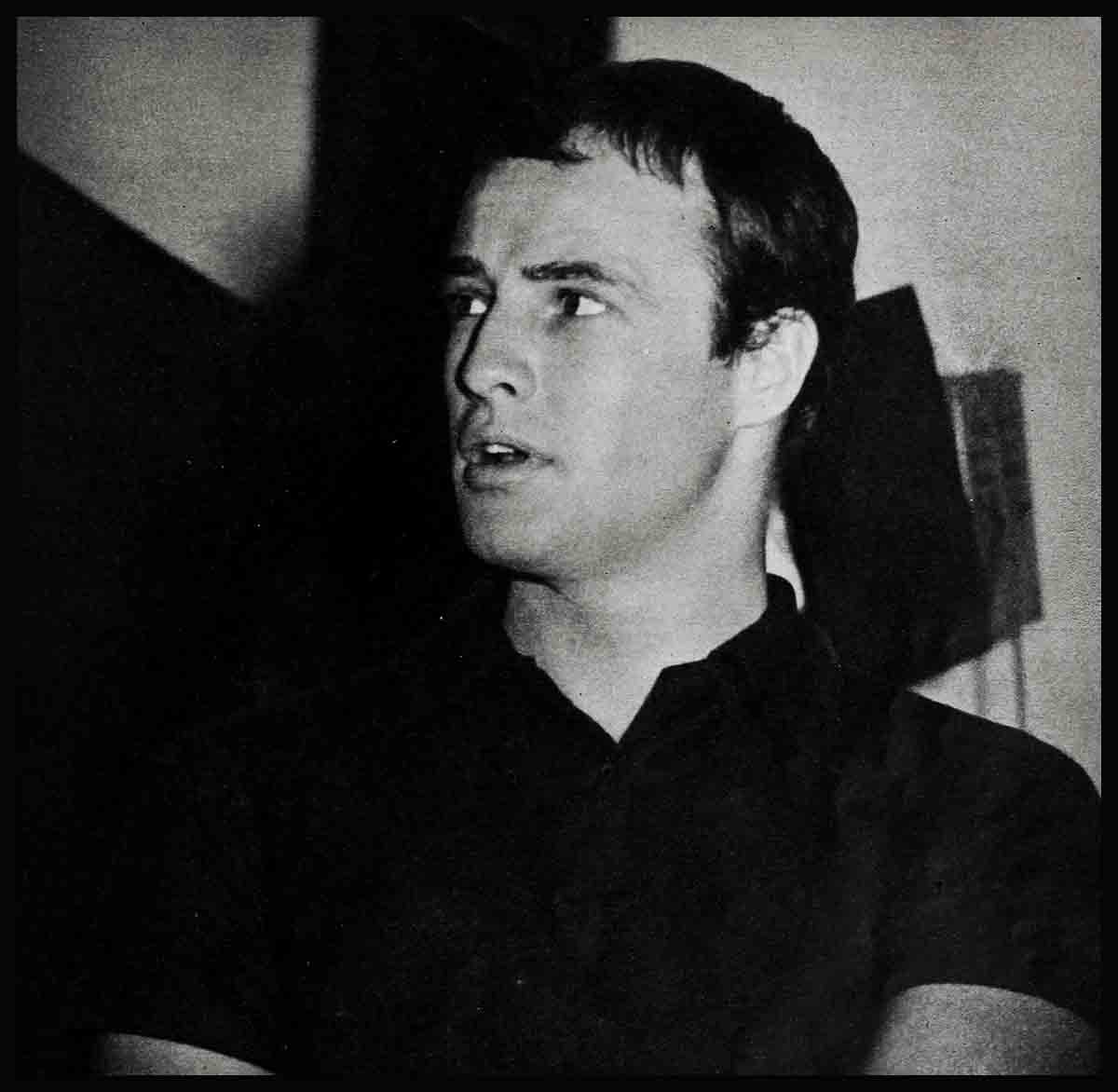

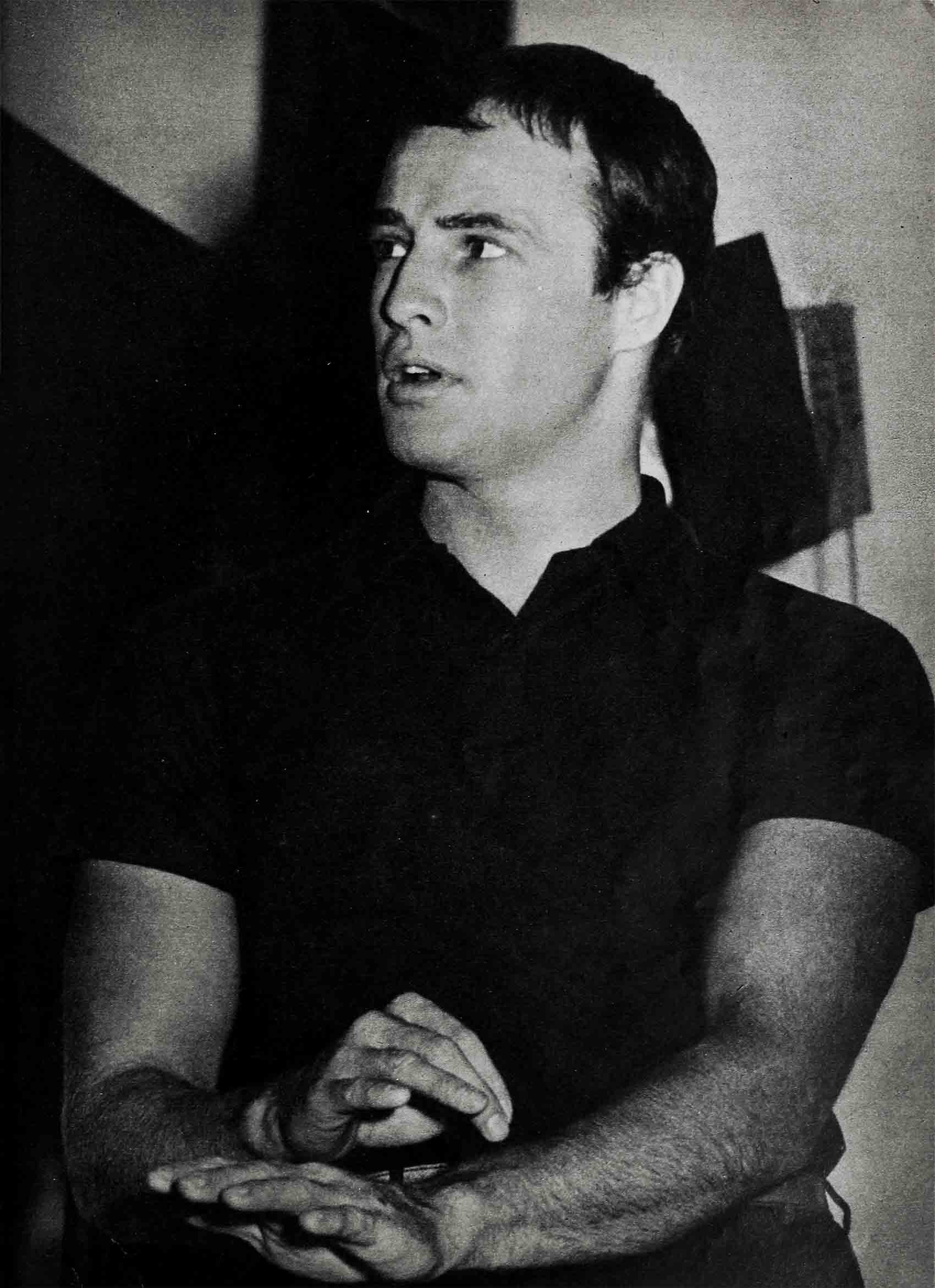

It’s A Brand-New Marlon Brando

“Look,” Marlon Brando said. “I’m not going to pose in any T-shirt. I’m tired of that screwball routine. From now on, I’m not going to have people say I’m a souped-up wack.”

Brando was talking to a group of photographers who were trying to shoot him on the set of Desirée where he had a few minutes off between scenes.

He looked around and borrowed a jacket from a friend. Slipping into it, he said, “Okay.” And the shutters started clicking.

“Got enough?” Brando asked presently.

The amazed photographers looked at each other. Was this docile, gentle, pleasant young man really Marlon Brando?

Was this the enfant terrible, the holy terror, the actor with the blazing, unpredictable temperament? Was this the very same fellow they’d been warned against, the actor Twentieth Century-Fox had sued for $2,000,000 because he’d walked away from The Egyptian?

He was humble, cheerful and helpful—and on the Twentieth lot, too. Jean Simmons, his leading lady in Desirée, passed by and said voluntarily, “Marlon Brando is the greatest.”

The publicity men, notoriously jaded and sophisticated, agreed that they never had worked with a more cooperative player.

Were they all sincere or were they merely climbing on the bandwagon because Brando is expected to win an Oscar for his superlative performance in On The Waterfront?

The answer is that Marlon Brando, the most enigmatic and talented young actor Hollywood has ever known, has turned over a new leaf. Ever since April, Brando has been a relatively new man—new in his attitude and in his behavior.

He has become outgoing. He has developed great warmth in his personal relationships. He likes people instead of fearing them. His conduct with Josanne Mariani, is different from his old manners with women. Josanne is a black-haired, brown-eyed Corsican actress Marlon had met in Europe. When Josanne came to Hollywood, she visited him on the Desirée set each day.

He was kind, considerate and attentive to her. In the past he’s been chary of showing any affection to a girl, particularly in public. But with Josanne he was every inch the courting gentleman.

When newsmen asked if they might take her picture with him, Brando grinned and shook his head.

“You better not,” he said. “Don’t you think so? We’ve got no right to intrude on her privacy.” Because Brando was so gracious, the photographers agreed.

They saw Josanne around Hollywood a great deal. Phil Rhodes, Brando’s friend, used to drive her to and from the studio, and they could have photographed her a dozen times. But why get Bud Brando sore when he’d gone out of his way to help?

Who is responsible for Brando’s new attitude? Why has he changed his tune?

Only a year ago he was saying, “I’ve had enough of Hollywood. Came out to the movies for only two reasons: loot and experience. Now I’ve got ’em both and I’m pulling out.” He talked about going to Europe and to the Far East and making pictures there but he was defintiely soured on Hollywood and its ways. He claimed that unjustifiably he had been depicted as an irresponsible screwball. After Julius Caesar, he said, it would be a long while before he hit the West Coast again.

For a while he was true to his word. He flew back to the East and presently his girl, Movita Castaneda, joined him there. Gradually, Movita helped weaken Bud’s prejudice against Hollywood.

“You’re too sensitive,” she told him. “You take everything so much to heart. Why do you care what they say about you? They think you’re rough and crude and crazy. But all the people who know you, all the people who’ve worked with you like and respect you.”

But Bud was still hurt.

When Julius Caesar opened in New York, he declined to attend, explaining, “I just couldn’t go through it.”

Asked if he’d read the wonderful reviews, he said, “I never read reviews. They either praise you or kick you. But they don’t help you.”

Then Stanley Kramer, the producer for whom Brando had made his first Hollywood movie, The Men,telephoned to say that he was making a picture to be called The Wild One, and he wanted Brando, that he needed him badly. Would Bud come out to Hollywood and do this one favor?

Bud went. He has an indomitable sense of loyalty and friendship.

He understood that certain of his pals would get minor parts in The Wild One. They didn’t and he resented it deeply. After the film was finished, he said, “I’m getting out of Hollywood and this time I’m really staying out.” Once more he flew to New York where he signed to play in summer stock for a friend at $125 a week. Bud has great admiration for Elia Kazan, the talented stage and film director. It was Kazan who gave Brando his first big break by casting him as Stan Kowalski in A Streetcar Named Desire.

In New York, Kazan began to talk with Bud about a script by Budd Schulberg dealing with waterfront scandals.

Brando agreed to make the picture. Most of it was shot in Hoboken, New Jersey. Bud loved making the picture. He reported to work each day in work trousers and leather jacket. He rode the trains and subways home hardly ever being recognized. When he was, he signed autographs until his fingers were numb. Never in his life has he refused an autograph.

In the Waterfront film, for example, Sam Spiegel, the producer, was a bit late in paying some of the featured players their salaries. Marlon raised a fuss about it.

“Sam,” he said, “you’ve got some nerve keeping these people waiting for their money. Where do you come off with that stuff? Spiegel paid off quickly.

After On The Waterfront was completed, Bud heard from his father Marlon Brando, Sr., that a cattle ranch was to be put up for auction in eastern Colorado.

“I’ve got about 800 head of cattle out in Nebraska,’ Brando says, “and I always thought it would be a good idea to have them feed on my own ranch. I’m partners with my father—we have a company called Marsdo, Inc.—and my dad said we needed another $150,000.

“Just about then MCA, my agents, called and said that Fox wanted me for The Egyptian. I could get $150,000 for the picture. That seemed to be the answer.”

When Brando arrived in Hollywood early this year, he knew in his heart that he was going to work in The Egyptian for only one reason—money. That realization ate into him. He is a sensitive young man who from time to time has denounced money-mad persons as “unconscionable hucksters.”

The resulting struggle with himself turned Marlon so sick that he felt he must have the help of a psychiatrist. So he got on a plane before The Egyptian started and flew to New York and the care of psychiatrist Dr. Bela Mittelmann.

Immediately, the studio filed suit and replaced him with young Edmund Purdom.

A few weeks later Brando was told that his mother, Mrs. Dorothy Brando, was ill in Pasadena. He flew back to California at once. When Bud arrived, she was dying.

Bud and his mother had always been very close. Mrs. Brando knew that in Marlon she had something of a maverick. She loved her son and sympathized with him and tried to bring him comfort and hope. Before she died, she said, “Bud, I want you to get along with people, to love them instead of fighting them. Don’t fight with the studio, Bud. Don’t fight with anyone. Sometimes it’s hard but you must get along with people. You must love them. It’s the only way.”

Marlon said he would do his best.

His mother died on March 31. A few weeks later Brando made his peace with the studio and agreed to report for the role of Napoleon in Desirée.

The studio believed that he would be vindictive and antagonistic.

Instead Bud has been all sweetness and light, and extremely discreet. “I promised my mother that things would be okay.”

When Bud was asked about his reported breakup with Movita, instead of blowing his top as he would have done in the old days, he said calmly, “We’re still friends and Movita is still a very lovely person. But let’s not pursue that subject.”

Movita spoke more freely.

“Isn’t it possible,” she asked, “for a man and woman to have a friendship without its ending in marriage or a quarrel? Bud and I are still good friends. We talk over the phone every few days. But I never had any intention or desire to marry him. Apparently he’s not yet ready for marriage.

“Before he settles down to family responsibilities he wants to travel. Marlon is a wonderful person involved in the sometimes painful process of finding himself.”

Another young beauty who dated Bud in Hollywood and is convinced that he possesses all the virtues is Rita Moreno.

“I went out with Marlon a few times,” Rita said, “and he was a perfect gentleman. He’s relatively quiet, but when he speaks he says something worthwhile.”

Marlon’s explanation of the stories of his alleged weirdness is simple. “The press,” he says, “is responsible for spreading all those wacky stories. When I was in Streetcar in New York a woman came backstage to interview Jessica Tandy.

“Jessica was about to introduce her to me but I said quickly, ‘I know, Jessica—your mother!’ I wasn’t trying to be smart or sarcastic or anything. I didn’t have my glasses on and I’m nearsighted. But this woman never forgave me and has been giving me the business ever since.

“Then when I came out to Hollywood to do The Men, the publicity guys told me to go around and visit another columnist at home. I didn’t have anything to say, and when they told this columnist I wasn’t about to go visiting, I became ‘naughty, naughty Marlon Brando.’

“Then I was interviewed by some writers and frankly I was shocked by the questions they asked—so intimate, such an out-and-out infringement on a man’s privacy.”

Marlon admits he wasn’t “too diplomatic” years ago. “But I’ve learned,” he says, “and that’s why I’m not posing for any pictures in blue jeans and a T-shirt. I’ve got suits. I’ve got shirts. I know how to knot a tie. I want to destroy the impression that I’m constantly bumming around.”

As a matter of fact, Brando is now pursuing the opposite tack. Ata recent Hollywood party, he was the only guest to show up wearing a tie and jacket.

The girls he quietly dated in Hollywood also report that he was dressed formally when he came courting.

When Marlon finished Desirée, he was heading for the Venice Film Festival where Waterfront was to be entered in the contest.

“How about that Mariana girl?” he was asked. “Will you see her in Europe?”

Brando grinned. “I’m trying to be very cooperative with all the press people,” he explained. “I’m trying to be nice and helpful. But somehow I don’t ever think I can get to the point of discussing girls I know. A man is entitled to his private life even if he is an actor, and attempts to invade it—well, I still consider them outrageous.” But he said it good-naturedly.

A year ago he would have grown sullen and morose and stalked off.

There’s no doubt about it—it’s a new kind of Brando, with love and kindness conquering inhibition and fear.

THE END

—BY ALICE HOFFMAN

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE NOVEMBER 1954

No Comments