The Day I Discovered My Heart—Tony Perkins

It all started innocently enough. It was just a studio-arranged date. Neither of us. expected it to turn out the way it did. . . .

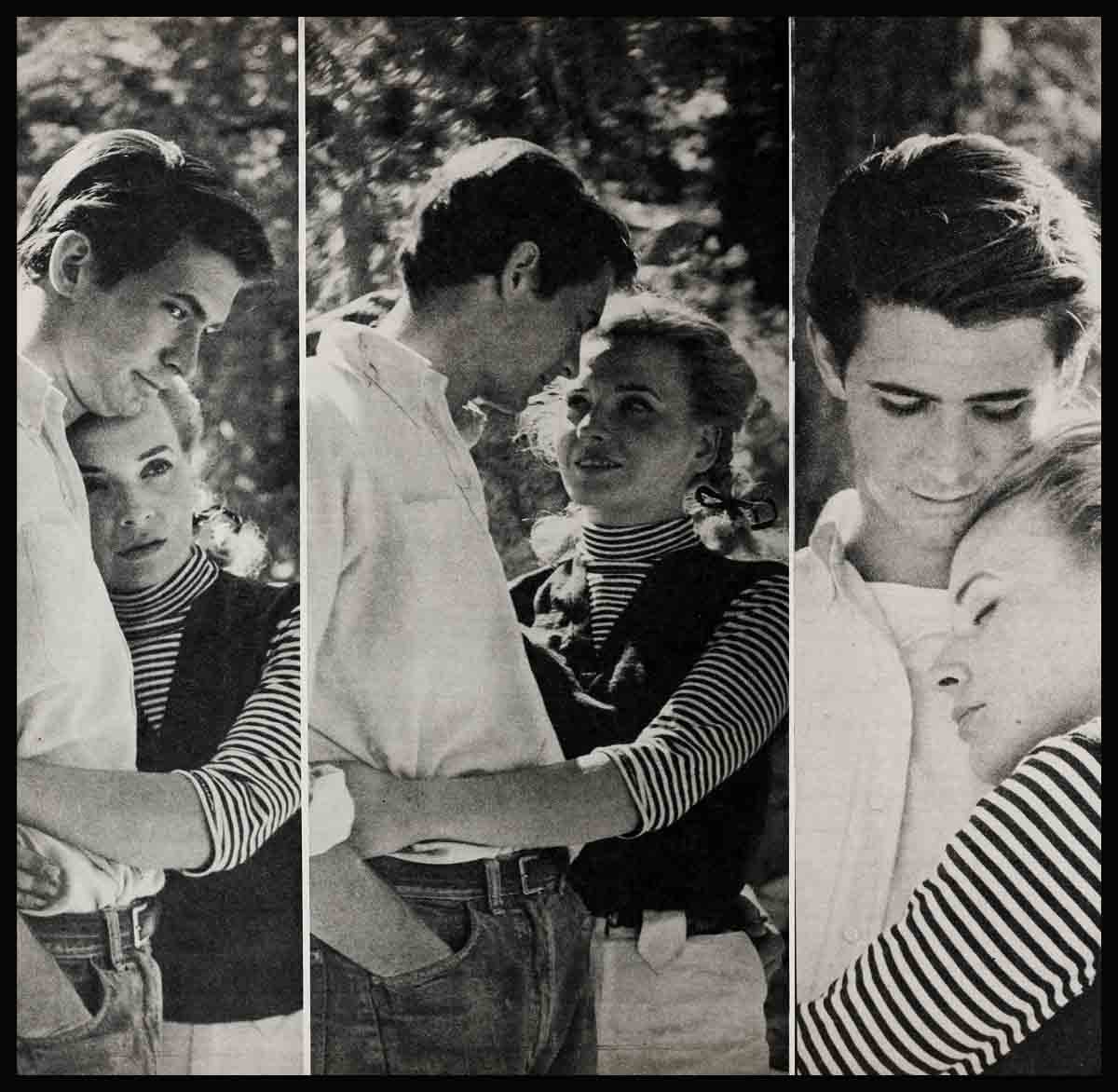

Elaine Aiken and I were in Lone Pine, California, on location for The Lonely Man. And on our first Sunday off from the movie cameras, we were asked by the studio. to pose for a magazine layout near Mount Whitney.

So, like I say, it all started o out innocently. It began as a picture date—more business than pleasure.

The photographer met us late that Sunday morning, and we drove to the Whitney Portal which is at the foot of the mountain. We drove out in two cars—Elaine and I in one, and the photographer and his assistant in the other.

The air was brisk, not too cold, the kind that puts a pink glow in your cheeks and warms you inside.

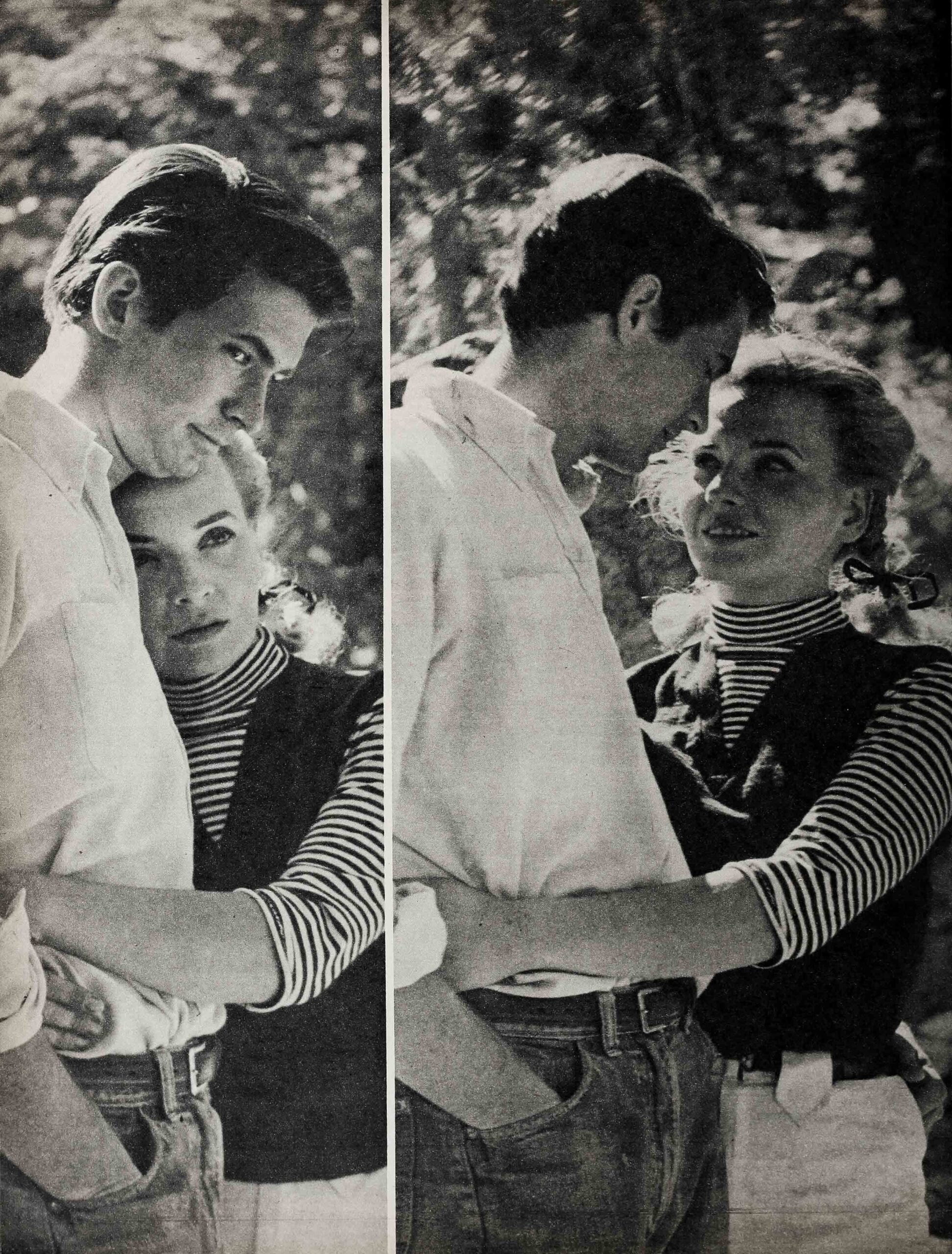

When we arrived at the spot the photographer wanted for the setting, the air was so invigorating that Elaine and I began to race around the trees, around the lakewater which was as blue as a summer sky.

The photographer was pleased. He preferred taking candid pictures. He didn’t like formal poses—and so he took a slew of candids.

It was then I realized how enjoyable Elaine was. She was willing to try anything I wanted to try. If I wanted to climb trees, for instance, she’d go along with me. If she scraped her hands on the tree trunks, that didn’t matter. She wanted us to have fun, and she let me be the leader which, no matter what they say to the contrary, a fellow likes.

Don—the photographer—took innumerable snapshots. About two o’clock in the afternoon I said I was famished, thinking we’d head back to the diner in Lone Pine for hamburgers.

Elaine ran to the car, took out a canvas bag, and gave me the surprise of the afternoon. She had packed a picnic lunch! A little early in the season for picnics, yes, but very thoughtful.

She had fixed it all the night before. We were living in a motel court while we were on location, and we all had tiny alcove kitchenettes in our rooms. The kitchenettes were the kind where you have a pint-sized refrigerator and a small stove on top of it and a baby sink that your two hands barely fit into when you wash a coffee cup.

Elaine really did a bang-up job with the picnic food. She had fried chicken and hard boiled eggs and potato salad and pickles and a chocolate layer cake—which she confessed was store-bought—and milk.

Picnic in the car

We all sat in the car the studio had loaned Elaine and me for the day, and we devoured the food. I never thought Elaine had it in her, this talent for cooking, so it came as a pleasant shock to me.

We told funny stories while we ate and we looked at the vast mountains and the calm lakewater. There was a peace about the surroundings which was comforting after the hectic week we had in front of the film cameras. The sun was bright, and it gave the snow a dazzling sparkle. And the air was fresh and bracing.

We finished our food and thanked Elaine. Don said the picture-taking was over, as far as he was concerned. We could return to Lone Pine and our motel.

I didn’t feel like breaking up the party. Don and his assistant were putting their stuff away in their car, and I looked at Elaine.

“Do you feel like going back?” I asked her.

“Doesn’t matter,” she said. “What would you like?”

I hemmed and hawed like a jerk. Women are so much better at expressing themselves. I wanted to stay, but I was ashamed to say it out loud. I didn’t say anything. Elaine came to the rescue.

“Would you like to stay?”

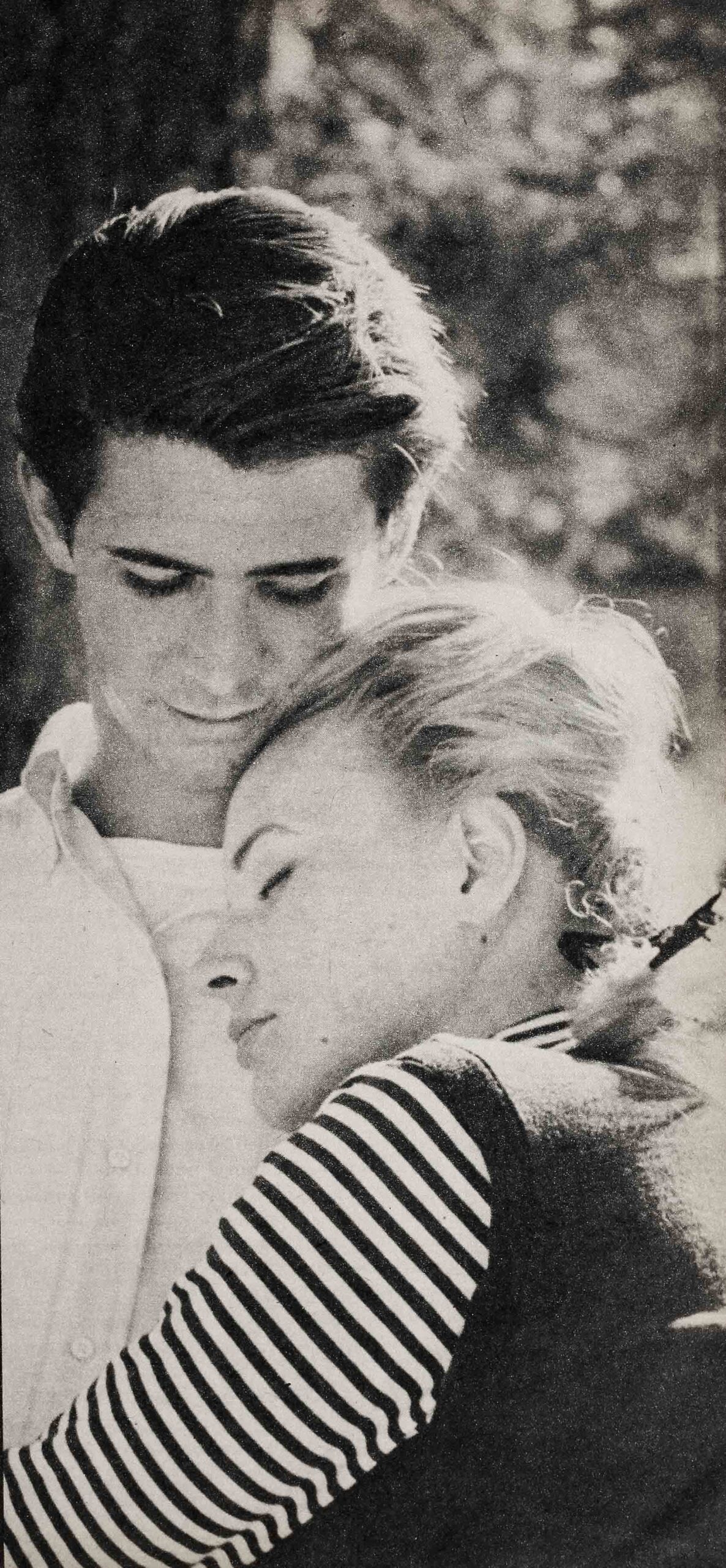

When she said that, I realized she understood me. She knew I wanted to stay. She was tuned in to my feelings.

“Yeah,” I said. “It’s so nice here. How you? How do you feel about it?”

“Sure,” she said. “I’m game.”

So we told Don to head back to town. We were going to explore the Mount Whitney country. Don and his helper left, and we waved to them as they traveled down the long, winding road.

Elaine and I were both smiling.

“I’m glad we stayed,” she said. We took a hike and looked for animals. We never saw any close up, but we did hear a lot of different animal noises. Elaine yelled out to me when she saw a flash of red wings in the treetops but we couldn’t make out if it was a cardinal or a red-winged blackbird. Far off, on snow-capped Mount Whitney, it seemed to me as though I saw a coon, but his coloring camouflaged him. When I went to point him out to Elaine, we could no longer see it. He was gone.

We returned to the car and the sunlight was beginning to wane. I turned on the radio, but couldn’t get a decent music program. There were either operatic selections or preachers lamenting the crisis in education.

Mountain dance

Elaine fiddled with the dial and in a few minutes, picked up a Nevada disc jockey who was hip on rock music. We listened to the program for a while.

“Let’s dance,” I said.

I turned up the dial all the way. We got out of the car and began dancing right out there in the open. I swear if anyone saw us they would have called us nuts.

But I couldn’t care less if someone did see us and say we were crazy. For the first time in my life I was really relaxing on a date. Elaine made me feel like myself. She didn’t push or press me in any. way. She let the conversation flow naturally. She was herself, I guess, and I was myself; it was wonderful to know that two people could get to know each other like this.

We danced in the setting sun, hardly noticing that the day was getting cold and dark. We danced to Elvis and Fats Domino and LaVerne Baker.

Evening comes early up there in that Whitney country, and so I figured the day had ended. We would go back to Lone Pine, and that was that.

We got into the car and began driving back. I was saying to myself that I didn’t want our day to end. I was hoping by some miracle it wouldn’t. It was too good to give up.

We arrived in Lone Pine and were driving along the main drag to our motel which was called The Portal. The neon sign of one of the restaurants caught my eye. I had to be reminded that we would have to eat soon. I guess men wait for their appetites to remind them. They never think ahead.

I suggested we go to our cabins to shower and dress and then go out for dinner and do the town.

She responded enthusiastically. But she added, “Let’s not expect too much of Lone Pine.”

Now Lone Pine is a hamlet of only a few thousand people. A general store, a saloon, a movie house, a barber shop, an alderman’s office and not much else—that’s the main drag of Lone Pine.

Both of us were used to living in big cities that have all kinds of entertainment within arm’s reach. In New York you can go to the theater or any movie of your choice on the spur of the moment. Movies play at hundreds of movie houses all hours of the day and night. There are restaurants everywhere—two, three and four in a block; and there are all kinds of them—Chinese, French, Greek, Mexican or plain old steak-and-potatoes American. If you like symphonies, there are concerts. If you like night clubs, they’re everywhere in town. So to ‘do the town’ in Lone Pine might take some meditating.

I parked the car in the motel courtyard, and I left Elaine at her cabin which was next to mine. We agreed to meet in a half hour.

Getting ready for a big night

I showered and shaved and put on a white shirt and tie and my dark brown herringbone suit. I was excited. Our day was turning out to be an adventure. We hadn’t expected it to be this way, and suddenly we were looking forward to spending the evening together.

When I went next door to pick her up, she was dressed up, too. She was wearing a smart neat-fitting red wool dress, little pearl earrings and high-heeled shoes.

She put on her coat. I was wearing my raincoat. We headed for the main drag of Lone Pine which was about a block long—like a Western frontier town.

We didn’t have much choice of restaurants. We walked to the one where the neon sign had attracted my eye.

The restaurant was called Mama Theresa’s. It was Italian. We weren’t full-fledged movie stars in the sense of people recognizing us, so we entered unnoticed. Anyway there weren’t many people eating.

Mama Theresa’s was small but cozy. The tables had red-checked tablecloths, and there were candles stuck in old raffia-covered wine bottles. There was a white trellis in the back covered with crepe-paper flowers, and it masked the kitchen area. In a corner was a juke box, and I got up and played some of the songs. All the titles were in Italian so I just punched a bunch of numbers, and in a minute the place was lively with that jumpy music I call Italian rock-and-roll.

An old man with a big white mustache and his fat wife, Mama Theresa, ran the place. I asked then what we should order, and he told us they’d take care of everything.

It was one of the best Italian dinners I’ve had in my life—Italy included.

We started off with a terrific antipasto. Then veal cutlet parmigiana, a side order of spaghetti al dente and a fresh green salad. It was so good, all of it, that I decided to celebrate and order red wine. I never drink, but this was turning out to be a special occasion.

The old man with the mustache served us the wine, and Elaine and I both toasted to the future and the good things it would bring.

For dessert we had spumoni and espresso coffee.

We could barely move from the table when we finished. The other guests had left, and the old man with the mustache and Mama Theresa showed us around the kitchen with its gleaming pots and wooden workboards.

They told us about the time they immigrated to America from Italy, and how they loved the United States, their adopted country. It was good to them, they said. It gave them work, and they raised their children and were able to send both their boys to college. They showed us snapshots of their sons who were handsome and rugged-looking.

After we said arrivederci—goodbye in Italian—we walked along the dark, empty street.

We window-shopped, looking into the few lighted store windows. The most exciting window in Lone Pine was the hardware emporium’s—there were all kinds of guns, knap-sacks, fishing tackle and bowie knives.

At the end of the street there was a dimly-lit pool parlor, and we walked in and watched some cigar-smoking, red-skinned Indians shooting pool.

A new game

We played some pool, Elaine and I. She had never held a cue stick in her life, but she told me she was willing to learn so I taught her a few fundamentals and we played a couple of games.

It was eight-thirty when I looked at the clock on the wall in the poolroom. I asked the Indians when the last movie was playing. They told us around nine. . . .

After the movies, we went to the soda parlor next to the movie house. We read movie magazines on the racks and wondered if we’d ever be in them, if we’d ever become important movie stars.

They kicked us out of the soda parlor because it was closing time.

But I didn’t want to go home. We walked in the direction of The Portal, our motel. Behind our motel was a baseball diamond with billboard ads—BUY MOXIE, BUFFERIN FOR QUICK RELIEF, GET RID OF YOUR FIVE O’CLOCK SHADOW. The moon was floating high in the sky like a bubble, and it cast a beautiful bluish light on the baseball field. We held hands and walked around the diamond; we touched the bases and looked at each other in the moonlight. Then I brought Elaine home to the cabin, wishing that we were just starting out, that it was Sunday morning and we were getting ready to go to the foot of Mount Whitney for the picture-taking.

Maybe you can’t believe it, but this was the greatest date of my life. It was so simple that we were very relaxed, and consequently we discovered each other. And I discovered something else too—I discovered my heart. I’ve never been able to discover a girl in the same way as I did Elaine—maybe because I’ve never experienced such an easy-going date again. Elaine and I talked about easy things, un-pretentious things. We were honest and down-to-earth with each other. When we held hands walking around the baseball diamond in the moonlight, I really felt a communication with her. I felt I had gotten to know her. We had shared something unexplainable. . . . and made a wonderful discovery.

THE END

—BY TONY PERKINS

Tony is now appearing in THIS ANGRY AGE for Columbia, and in Paramount’s THE MATCHMAKER; he can soon be seen in GREEN MANSIONS for MGM.

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE SEPTEMBER 1958