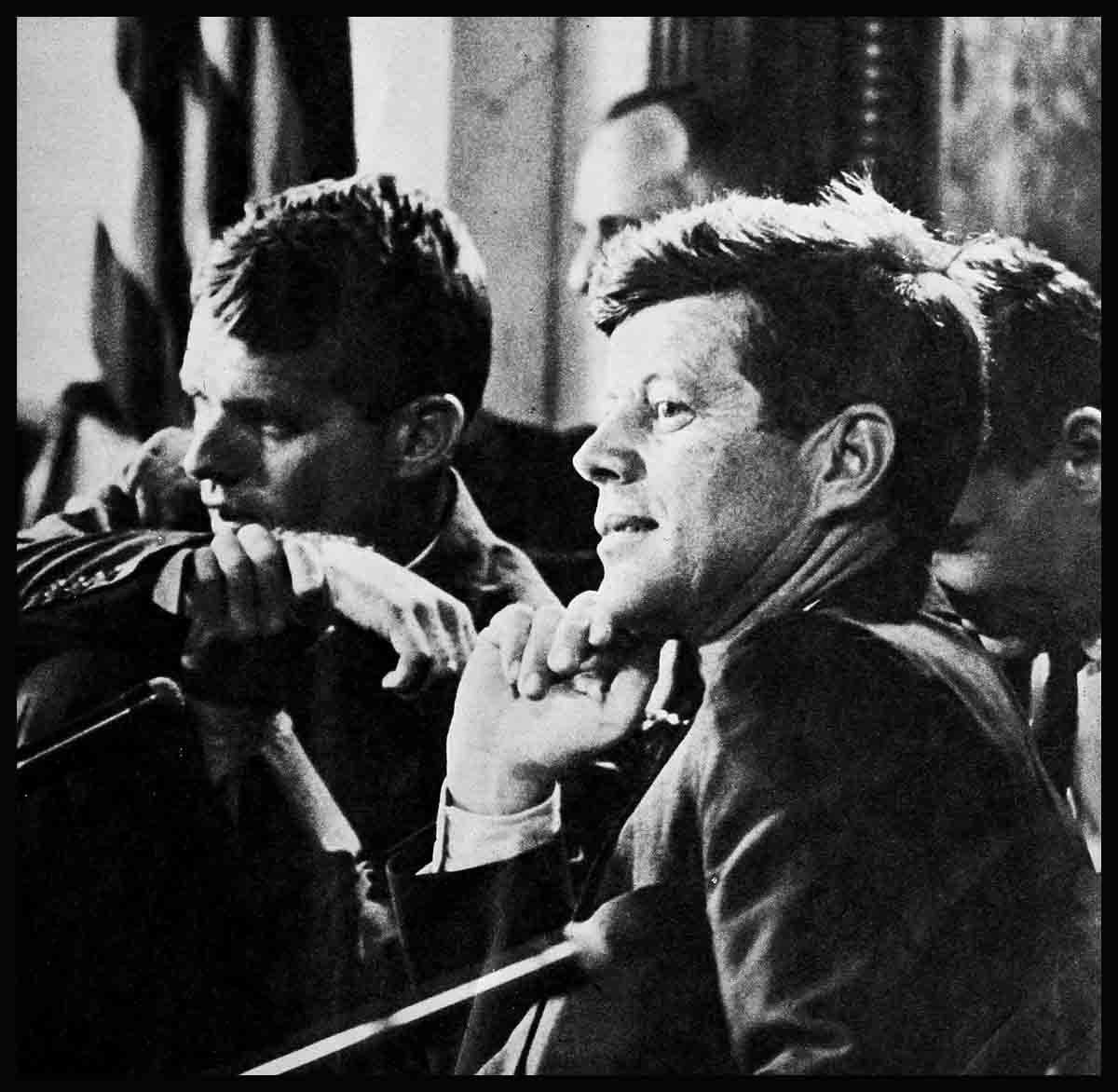

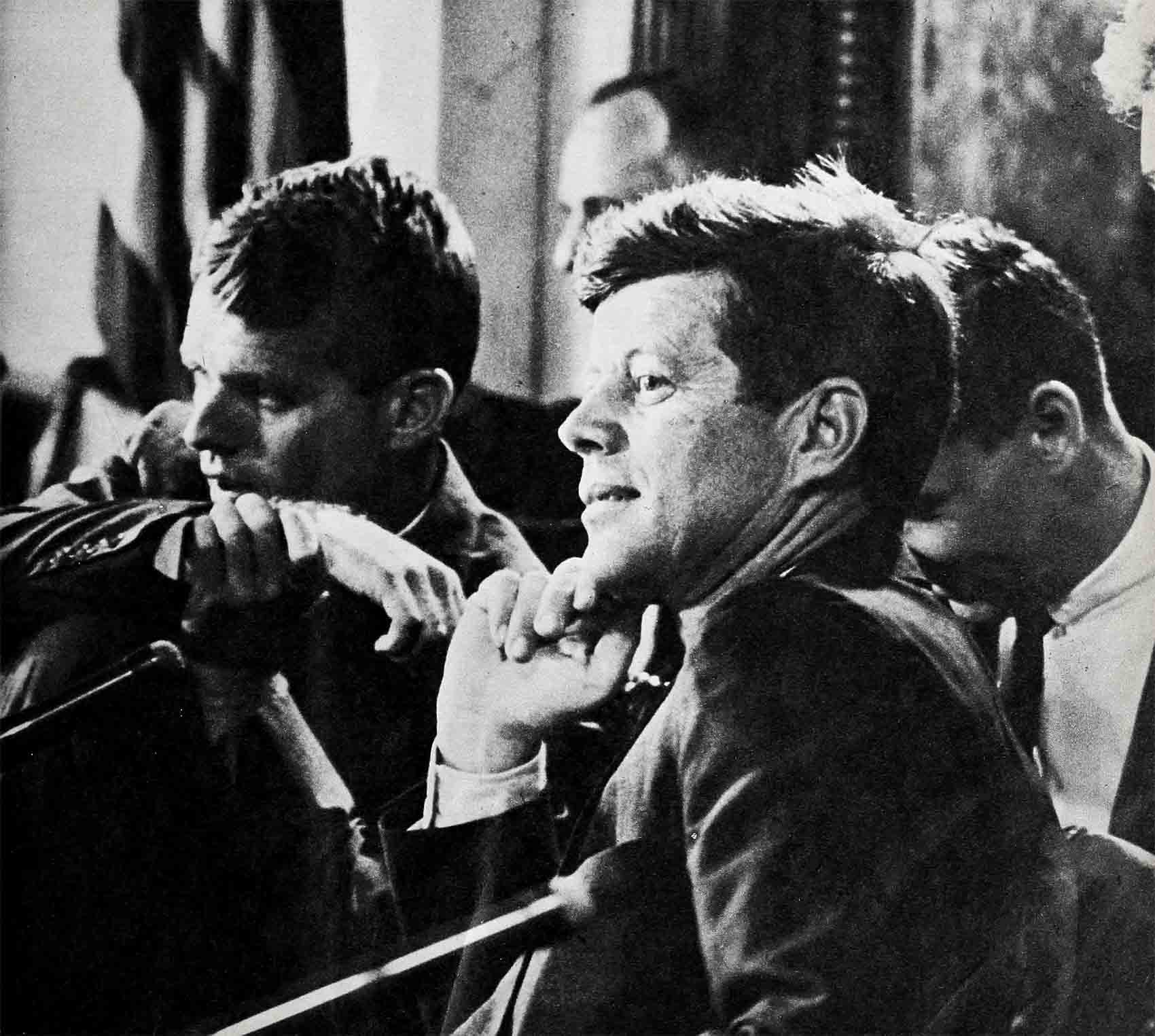

Bobby Kennedy

You’ve probably seen those ads. On one side there’s a “before” drawing: a thin, scrawny fellow is lying on the beach. His girl, sitting next to him, is glancing admiringly as a big, strong brute kicks sand in her date’s face. On the other side of the page is the “after” picture—“after,” that is, the skinny fellow has taken a six-week course in body building. Now his girl has eyes only for him and his brand new muscles.

The “before” and “after” story of Bobby Kennedy, the President’s kid brother, isn’t mainly a case of brawn and muscle. But the transformation from a shy “boy most likely to recede” to the “second most important man in the United States” is equally miraculous and unbelievable. His tremendous change wasn’t accomplished in six weeks or six years—but it did happen. And there was a woman beside him, too.

An early color portrait of the Kennedy family reveals the “before” character of Bobby as vividly as the “before” drawing in the physical culture advertisement exposes the dilemma of the scrawny weakling. In the faded photo, you can hardly see Bobby. His slight figure (today, he is still only five-feet-ten-inches and weighs one-hundred-fifty-five pounds), his bland blue eyes (almost covered by his tousled hair) and his round face are all very unimpressive. His expression (what you can see of it) is shy. But more significant, he is lost among his glamorous sisters and brothers—particularly his two older brothers: Joseph Kennedy, Jr. and John Fitzgerald Kennedy. Bobby must have seen the photo and come to the same conclusion, for somewhere along the line he decided to fight his way to the center of the family picture. And to do that, he had to test himself, to discover the depth of his own courage. His initial test came in prep school, at Massachusetts’ snooty Milton Academy. It didn’t cut any ice with his classmates that lie was an ambassador’s son ; what mattered to them was that he was a Catholic, and there hadn’t been many Catholics before at Milton. So they hazed him mercilessly and topped it off by breaking in and messing up his room.

Bobby struck back immediately. He went into the room of the ringleaders, threw open the window’s, and hurled everything he could find—books, clothes, furniture, pictures—out on the grass. That did it: he was accepted and went on, as quarterback. to lead his school’s team to a gridiron championship.

Later at Harvard, however, he was restless. The United States was at war and the history he was reading in books seemed pallid and meaningless compared to the history being written each day in newspaper headlines. His brother John was somewhere out in the Pacific commanding a PT-boat. His brother Joe had given his life to his country in an attempt to knock out a Nazi V-2 missile base. Yet here he was going to classes—not to war!

So he reversed the stereotyped notion of what a rich boy does in time of national emergency. He pulled strings to get into the conflict. Ironically, and even though he protested, he was ordered aboard the newly commissioned destroyer U.S.S. Joseph P. Kennedy, Jr., named after his heroic older brother. There, as a seaman second-class, he spent twenty-seven miserable months. The only action he saw was the dirt disappearing as he swabbed the decks.

Frustrated in his attempts to be a war hero like his brother Jack—who had accomplished feats of valor in the Pacific—Bobby returned to Harvard and set his sights on being a football star. But when the team photograph was taken in his junior year there was Bobby, a third-string end, once more almost out of the picture.

As a senior, Bobby actually started a game against Western Maryland, and he probably had visions of catching the winning pass against Yale in the final seconds of play. And of finding his photo, blown up to hero’s size, in the paper the next day captioned, “Final score: Bobby K.—7. Yale—6.” A dreamy, hero-style picture!

But the picture was wrong. As a friend tells it: “Bobby broke his leg trying to block a play around his end (this happened in practice), but he didn’t tell anybody. The coaches kept screaming at him and running the play over. Bobby was crying but he kept limping around and missing the block and trying again for fifteen minutes before he collapsed.”

He did get into the Yale game—for one play, hobbling onto the field and limping off again. The crowd in the stands applauded him perfunctorily, but the loud cheers, as usual, were reserved for others.

Enter Ethel

Kennedy discovered that being in the center of the picture—or being the only one in the picture, the conquering hero—wasn’t the most important thing in life. It was a pretty young girl, Ethel Skakel, former roommate of his sister Jean at Manhattanville College, who changed him.

Bobby met Ethel at a Canadian ski resort one weekend away from the University of Virginia, where he was a law student at the time. Maybe it was the way a silly little bow bobbed up and down in her hair as she raced him down the ski slope. Maybe it was the way her tongue got twisted when she was excited and the words came tumbling out all wrong (out somehow just right for him). Maybe it was the way she matched him shot for shot in golf, serve for serve in tennis and stroke for stroke in the pool (and miracle of miracles, she was good at touch football). Maybe it was the way she competed as furiously as he did. (She once said: “I like competition, but I like to win better.”) Maybe it was the way she looked at him and smiled, so that he felt bigger than Goliath, stronger than Samson and smarter than Solomon. Whatever it was, he had fallen head over skis in love.

And so they were married. Now, with Ethel at his side, Bobby began moving towards the center of the Washington political picture—first as junior attorney in the Justice Department, Criminal Division. Then in 1952, when Jack ran for U.S. Senate. Bobby took over as campaign manager. He got it organized in three weeks flat—in his way—no velvet gloves. JFK remembers wryly, “Bobby works at a high tempo, he can be a little abrupt. Some politicians came into our headquarters and stood around gabbing. Finally Bobby told them, ‘Here are some envelopes. You want to address them, fine. Otherwise wait outside.’ They addressed the envelopes.”

After Jack won, Bobby worked for the Hoover Commission; on the legal staff of Joseph McCarthy’s Senate investigation subcommittee; walked out in protest against tactics and later returned as counsel for the Democratic minority.

But the real opportunity, the real challenge, came unexpectedly in 1954 when he was appointed chief counsel of Senator John L. McClellan’s committee investigating labor and management racketeering. Suddenly Bobby Kennedy was almost in the center of the picture, the main figure in a crucial struggle against Jimmy Hoffa, the dynamic, slippery leader of the Teamsters Union, who termed Bobby “a young, dim-witted, curly-haired smart-aleck” and “a ruthless little monster.”

In the course of that battle, which Bob I eventually lost, Ethel was always within smiling distance at the hearings. It was almost the only way she could see him. Life magazine called her an “ever-present—usually pregnant—figure in her husband’s budding career. Jack Kennedy says, “Every day for nearly two years, Ethel sat during the Rackets Committee hearings watching Bobby. She even looked at me once in a while. With that loyalty, I decided she was my kind of sister-in-law.”

And Bobby always found time for Ethel. Once, in the middle of a hot question-and-answer session she phoned, and then immediately forgot what she called him about. But instead of blowing up, Bobby grinned, murmured, “Oh Ethel,” and let her chatter on—while the witness he’d been grilling sat in a cold sweat, wondering what piece of sneaky evidence was putting that smile on his face.

Bobby took the verdict of “Not guilty” on Hoffa philosophically. Maybe now he’d have more time to spend with Ethel and enjoy his kids. Maybe he’d even count the rabbits at their seven-acre, fifteen-room estate at Hickory Hill in McLean, Virginia. There should be thirty rabbits, or was it thirty-two? Maybe he’d get reacquainted with the rest of the kids’ menagerie three horses, four Shetland ponies, two goats, a gaggle of geese, some baby chicks, three man-sized dogs, one kitten, a flock of ducks, four pigeons, two sparrows, one cockatoo, one parakeet, one “sort of mixed-breed parrot,” six turtles, one tortoise, one burro and twenty goldfish. No counting the seal and the sea lion the boys kept in one of the bath tubs until they were presented to the zoo. Maybe he’d even climb up into the treehouse—what one visitor had called “the only treehouse in the world that looks as if it were designed by an architect”—and sleep.

But all his “maybes” went down the drain when his brother Jack decided he wanted to be President of the United States. Again Bobby plunged over his head into work as manager of his brother’s campaign. Again the only way Ethel could see him was to join him—this time on the vote-getting trail, which she often did. Bobby’s father, Joseph P. Kennedy, Sr., gave his son the highest possible compliment for his efforts during the campaign. “Jack works as hard as a mortal man can,” the elder Kennedy said. “Bobby goes a little further.”

Bouquets and brickbats

These were kind words, a loving accolade from a proud father to his son. But there were other words. Look staff writer Peter Maas questioned Bobby about some of the milder of the epithets hurled at him like “cold,” “ruthless,” and “arrogant.” Bobby replied: “If my children were old enough to understand, I might be disturbed to have them find out what a mean father they have. I’ve been in a position where I have to say no to people, and at times I have stepped on some toes. I guess a lot of this came out of the Los Angeles convention. But we won, and we won fairly, then and later on. We weren’t just playing games.”

Once again, a comment of his father may be applicable. “He’s a great kid. He hates the same way I do.”

They won. Jack and Bobby won. Jack was President of the United States, and Bobby was “Father of the Year in 1960,” and he didn’t want just the honor, he wanted to play with his kids.

But again Bobby reckoned without his brother’s wishes. His brother had plans for him, big plans. He wanted him to be Attorney General of the United States.

Bobby protested. Such an appointment would expose Jack to a barrage of hostile criticism. They’d accuse him of establishing a Kennedy family monopoly in the Federal Government.

The President countered, “We’ll announce it in a whisper at midnight so no one will notice it.”

Bobby persisted. He anticipated the opposition’s contention that he’d never actually tried a case in court.

(The President countered that one by saying, “I can’t see that it’s wrong to give him a little legal experience before he goes out to practice law.” Bobby told him he didn’t think the statement was very funny. Jack replied that he’d have to learn to kid himself, because people warmed up to that. “Yes, but you weren’t kiddingyourself,” Bobby retorted. “You were kidding me”)

Bobby turned a deaf ear to all his brother’s formal arguments, but he couldn’t shut out the tone of the requests. Jack needed him; that was the main thing. This was the factor that swayed Bobby.

As Bobby commented to a friend, “I began to realize what a lonely job the Presidency is. And I realized then what an advantage it would be to him to have someone (in the Government) he could talk to.”

So Bobby accepted the job. On the telephone, when he said yes, he paraphrased Dwight Eisenhower’s defense of Sherman Adams by quipping, “Why don’t you say I may be your brother, but you need me.”

A storm of criticism did break over the Kennedys’ heads. Opponents attacked Bobby’s inexperience, his youth (favorite Republican gag: “Why can’t I have a drink? I’m the Attorney General!”), and the fact that he was the President’s brother.

They also praised him with faint damns. One bit of gossip went: “Bobby, thank God, winds the President up every morning and heads him in the right direction.” Some “friends” wrote to JFK and suggested that Bobby would make a better President. He replied, “I have consulted Bobby about it, and, to my dismay, the idea appeals to him.”

But Bobby ignored the tumult and the shouting. He was too busy. As boss of the Department of Justice, he was in command of 31,000 employees, including J. Edgar Hoover and the FBI. For the first few days he bounded around the department, usually in shirt sleeves. He would pop into an office unannounced and say, “I’m Robert Kennedy. What do you work at here?”

After the shakedown period was over, Bobby settled down to the routine he knew best—work, work and more work. From 9:30 in the morning until 7 or 8 at night, including Saturdays and holidays, he sat behind his ping-pong-table-sized desk in a large paneled office—the walls of which are decorated with WPA-commissioned murals and kindergarten water colors painted by his seven children—and ran the department. His tie was always yanked aside, his mop of tousled hair was often in his eyes, his feet were either perched on his desk or he sat with one foot tucked under him. Most of the time a telephone was in his hand (memos take too much time to dictate; it’s easier to call directly), and he could be heard barking out his favorite slogans to workers in the field: “Stand up, speak up, then shut up” and “No chiefs—all Indians.”

“When I’m your age, Jack . . .”

When the President once chided him about his taste in clothes by saying, “Why, he’s still wearing button-down collars. They went out three years ago. Only Chester Bowles and Adlai Stevenson wear them anymore,” Bobby countered with a grin that he might change to “more mature” shirts when he reaches Jack’s age.

Sometimes Bobby’s casual attitude towards clothes and dress received public attention. As Life writer John L. Steele revealed: “During last spring’s Freedom Riders crisis he was suddenly called in from home one Sunday and came just as he was, fresh from playing with his children. He was photographed that day hard at work in denim pants, a sports shirt and a shapeless blue sweater.”

A few days later, he was changing in his office to go to a formal dinner party. But a new crisis arose and he spent the rest of the evening in his office, wearing a blue bathrobe over a pair of shorts, looking more like an office boy playing at being boss than the Attorney General.

But he is the Attorney General of the United States, even more important, he is the one person the President can talk to freely about the problems of government.

The one area where Bobby bows out and leaves the President on his own is the matter of social activities. The Attorney General is the President’s gadfly in government, but he is not a social gadabout. Rather than attend a big party or visit a night club or go to the theater, he prefers to stay home with Ethel and the kids. Instead of fancy deserts he goes for chocolate ice cream topped with chocolate sauce; instead of vintage wine he loves milk—a bottle at a time, deep frozen for fifteen minutes. Instead of swank restaurants, he gets more of a kick out of taking his wife and kids to a neighborhood Howard Johnson’s.

Even when he and Ethel do go to one of the famous cultural evenings at the White House, they break away early. Likely as not it will be Ethel’s turn to drive her own and the neighbor’s children to school next morning at 7:15.

At last count, Ethel and Bobby have seven children: Kerry, 2; Michael, 3; Mary Courtney, 5; David, 6; Robert, Jr., 8; Joe, 9 and Kathleen, 10. This number is subject to change without notice. (Not long ago, New York Daily Mirror columnist Mel Heimer announced, “The Bobby Kennedys expecting,” which has neither been confirmed nor denied—just ignored.)

Bobby and Ethel’s formula for raising their kids is to forget formulas and treat I them, as a child psychologist once said in another context, with “intelligent neglect.” Ethel says, “I guess lots of mothers would say I’m too permissive and too easy with the children, but I just don’t believe a child’s world should be entirely full of don’ts. We think it’s possible to have discipline and still give the children independence without spoiling them.”

She goes on to defend the Kennedy’s competitive credo, while acknowledging some of the problems. “I think that children should learn things when they’re young. Sure, there are risks—Kathleen broke her leg riding, Courtney her arm when she fell out of a tree, Joe his leg skiing. But gosh, if they’re going to develop independence they have to do it young! The less fear, the more they’ll accomplish.” (Ethel’s statement was made before another of the kids, true to the family tradition, busted two fingers falling out of the hayloft.)

Kind and loving parents

This recipe of independence, adventurousness and competitiveness is softened by large doses of parental love, liberally administered. Although Bobby’s superhuman schedule prevents him from seeing the kids very often, he makes up for the little time he has with them by making every second count. He’s gentle, thoughtful and infinitely patient with them.

The kids were left behind but were still very much in their thoughts when Bobby and Ethel, at JFK’s request, made a hurried trip to West Africa as a gesture of friendship by the United States towards the emerging African nations. Ethel won us a host of friends when, in a back country Ivory Coast village, she said, on hearing that a subprefect had ten children. “I’m jealous!”

Bobby was resplendent but slightly uncomfortable in a cutaway and new topper bought especially for the occasion—because Ethel thought that the top hat he’d worn at the Inauguration sank down too low over his ears. And he routed the Soviet diplomat, Daniel Solod, when he showed up at the outdoor reception given the Kennedys by Ivory Coast President Houphouet-Boigny. Solod had been briefed ahead of time that the Attorney General knew no French (the language of diplomacy at the Ivory Coast) and would return the President’s greetings with a few words of English. The communist representative left the reception hurriedly, however, when Bobby rose to his feet and read a thank-you speech in perfect French, a feat which also amazed his audience who murmured, “Vive! Bob-by speaks French!”

What neither Solod nor the others realized was that Bobby had practiced the speech over and over again on the plane, laboriously printing out the phonetic sound of each word.

Early this year, again at his brother’s request, Bobby and his wife were on the move again, bringing their unorthodox brand of off-the-cuff, personal diplomacy to fourteen countries in twenty-six days.

In Tokyo, although warned in advance that left-wing students might incite a riot. Bobby insisted on addressing a student rally at Waseda University. When heckled, countered: “It’s very possible that some of you will disagree with what I have to say, but under a democracy it’s the right of some to disagree.” When one student shouted at him from the floor, he invited the boy, Yuzo Tachiya, to the platform and let him sound off for eight minutes. Later, when Communists at the meeting sabotaged the P.A. system, the unperturbed Attorney General substituted a battery-powered megaphone and gave a lecture on democracy, filled with such Bobbyisms as “Pick up your marbles,” “The hell with you,” and “You’re crazy.” The students loved it, and at the end another youngster jumped on the stage and led the audience in the Waseda fight-song and in special cheers for Bobby. You would have thought that the visitor had single-handedly led Waseda U. to a victory over Nagasaki U. in the big game.

At a farming village outside Tokyo. Bobby unhooked his tie pin and presented it to Kohei Hanami, the local mayor. (Bobby seemed to have an unending source of these Kennedy PT-boat tie pins: on his West Africa trip he had unclipped one for a chef in the village of Orbaf. The chef was so delighted he forgot his disappointment that the distinguished visitors from the United States didn’t have time to eat the huge meal he had prepared for them.) But this time the presentation of the pin had even greater significance. For Mayor Hanami had been the commander of the destroyer Amagiri that rammed and sank Navy PT-boat 109, a craft commanded by John F. Kennedy, on August 1, 1943, and now memorialized in a book, a movie and a tie-pin.

A world of new friends

At Jakarta, Indonesia, Bobby braved hostile students again. Out from the audience came a cold fried egg, directed at the Attorney General. At the last second, as if he were ducking away from a high inside pitch in a softball game back home at Hickory Hill, Bobby moved his head and the egg plopped down harmlessly behind him. He spoke on as if nothing had happened, and at the close of his address the students cheered him to the rafters.

Towards the end of the trip, he completed a tour of the Red-constructed Berlin wall shortly after fifteen shots had been fired from the East zone. Thousands of Berliners chanted “Bobby! Bobby! Bobby!” before and after he laid a wreath on a wooden cross commemorating an old woman who had died in an attempt to escape to the West.

What was Ethel doing all this time? Well, she was the hit of a fashion show in Saigon; she almost fell into a canal in Thailand; she showed up for luncheon at Huis Ten Bosch, Queen Juliana’s Holland palace, without hat, gloves or bag, which caused a woman guest to purr, “They are a very ‘new style’ couple.” But, in a softer afterthought, she admitted that Ethel was “nice” and “completely natural”; she shopped in fourteen different countries for presents for her seven kids; she received rosaries for herself and each of her children directly from Pope John at the Vatican; and in a little talk at a German-American community school in Berlin, she let the cat out of the bag by revealing that her husband had flunked the third grade in his own schooldays.

Ethel’s most unusual adventure occurred at the Tuscan restaurant on the Piazza Fontanella de Borghese. The luncheon there started out just like any other meal until, without warning, six admiring newspapermen who’d accompanied the Kennedys on their world tour presented the Attorney General’s wife with a Vespa motor scooter. Someone started the engine by mistake, and the rest of the diners glared until another newsman found the shut-off button.

Ethel insisted on trying out the scooter immediately. So they wheeled it outside, she climbed on in her high heels, a newsman turned on the ignition, and away went Ethel and the Vespa. Around the piazza she sped as the Italian onlookers shouted, “Brava! Brava!” The Vespa grazed a slow-moving Fiat and the crowd yelled. No! No!” Ethel scraped her leg against a parked car and the spectators screamed, “Oh! No!”

Twice she sped around the piazza, three times, four times, and from the helpless expression on her face and the words she shouted as she whizzed past, it became obvious she didn’t know how to stop the darned thing. An intrepid reporter went to the rescue. He stood in front of the charging machine as a matador puts himself in the path of a raging bull. At the last minute he grabbed the horns—no, the handlebars—and wrestled the scooter to a stop. Ethel slipped off and smiled wanly. The audience exploded, “Bravissimo! Bravissimo!”

The German newspaper Morganpost summed up the unanimous reaction to the Kennedys’ good-will mission in an editorial : “Never before in the history of our city was a young man and his pretty wife received with such jubilation.”

When Bobby and Ethel returned home, seven children were waiting for them at Washington’s airport. Seven six-shooters were popped in their direction. Seven voices squealed in joy. Seven wads of well-chewed bubble gum were politely put aside for a minute while seven pairs of lips showered their parents with sticky kisses. Now there was a reception!

The next day Bobby was back at work—his brother’s eyes and ears and strong right arm.

Today. Bobby is only one step from the center of the family picture and, as his father has said, “If anything happened to me, Bobby would be the one who would hold everybody together.”

Ahead lies 1968. If brother Jack is reelected in 1964. Bobby may be in the very center of the political picture, with JFK as a-not-so-old elder statesman standing on the sidelines for him. For as a close friend has said, “It can hardly be conceived that Bobby won’t go into politics when he leaves the Justice Department. Yes, he might even run for President.”

Competitive Bobby is politician enough to play it cagey. He says, “Someday, per haps, I will run for elective office.” He also says, “If young people ever lose their drive to serve, then the country will be in trouble.”

Whatever Bobby decides and whatever Bobby does, it will be all right with Ethel. For she says simply, “Bobby and my children are really the only things that count.”

—BY JIM HOFFMAN

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE SEPTEMBER 1962

zoritoler imol

30 Temmuz 2023Good write-up, I am regular visitor of one¦s web site, maintain up the excellent operate, and It is going to be a regular visitor for a long time.