Deep In The Heart Of Hollywood—Audie Murphy

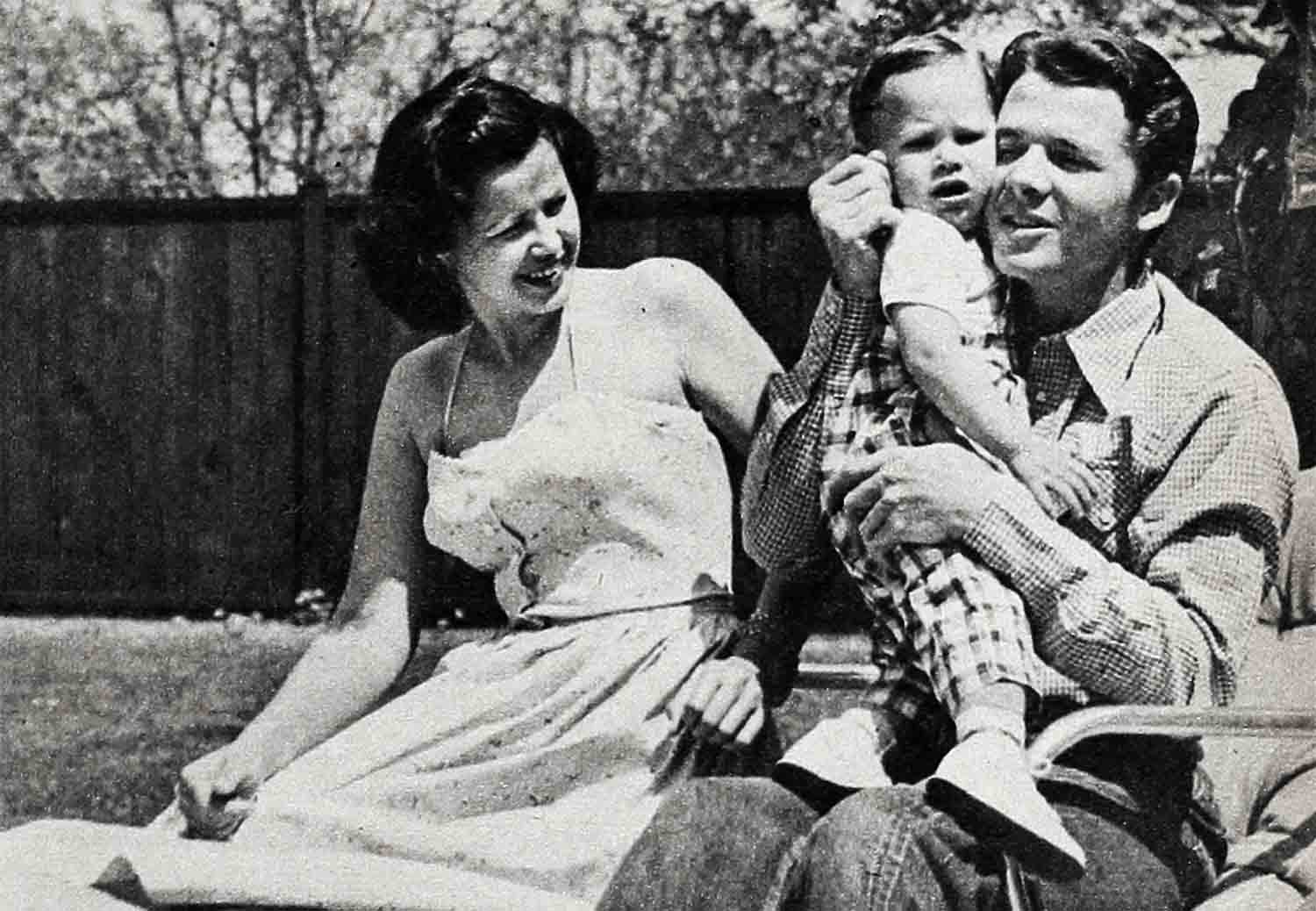

Los Angeles’ International Airport was fogbound. The plane Pam Murphy had come to meet was an hour and a half late. But for small Terry Michael Murphy it was very late. Ten o’clock was way past his bed time; he had gone to sleep in his mother’s arms. And there they both were waiting for Daddy.

Finally, Daddy—Audie Murphy—came bounding off the airliner to envelop them both in a big bear hug. Young Terry, aroused a bit in the transfer to his father’s arms, opened one eye to scan the situation and went peacefully back to sleep. Later, driving home, Terry made a movement, as if something had occurred to him in dreamland. This time he opened both eyes wide and reached over from Pam’s lap, easy like, to touch Audie on the shoulder. It was as if he said, “Are you really back, Daddy?” And having reassured himself Terry went back to sleep.

Audie drove to San Fernando Valley and left the hustle and bustle to turn into a side street. It’s a street of good houses, set invitingly back from the sidewalk. Shaded with walnut trees, it’s a street where kids ride bikes after school; with maybe an occasional pooch investigating what goes on at the neighbors’. You could easily imagine those neighbors borrowing that traditional cup of sugar from each other. But they wouldn’t be sending the maid for it. This street is one where people do their own chores.

Now the street was sleeping in the relaxed, clear night. But the inviting porch light that Pam had left on glowed on the quiet charm of the house. Redbarn Early American; 2,000 square feet. Not pretentious, but not crowded—just cozily roomy.

This is Audie Murphy’s home . . . the one he and Pam planned for, hoped for, looked for and finally found. Audie says, “Every time I think of paying for it, I get cold chills.” But he grins at himself, “Once people start wanting a home, it’s bad. You can’t leave the temptation alone. The only cure is to get one, if you want any peace.”

To Audie and Pam, this house will always represent Christmas. Not only because that was when they moved in, making it the nicest Christmas gift either had ever had. Pam says, “With all the beautiful decorations and the lights, the street looked so lovely.” It’s possible this house will mean Christmas even to Terry. Several nights he was allowed to stay up after curfew and toddle outside to look over the cheery, gay lights shining on the neighboring lawns.

When the Murphys were married on April 23, 1951, a small apartment seemed sufficient. By the time Terry arrived, like a timely income-tax exemption, on March 14, 1952, they had leased a house for a year. The house, described by Audie as “probably the oldest one in Los Angeles County,” was on a steep hill. Pam used to lug an assortment of groceries, Terry, and his pram or his walker up that hill. She learned to balance them all nicely; but getting the car up the incline into the garage was a feat she never quite mastered with ease. Then Terry turned out precocious; he was walking at the ripe old age of nine months. “Terry,” says Audie, “would sure as heck have fallen off that hill by now.”

Now, the Murphys are home. But when Audie sighs, “Home at last!” it’s a tossup whether he means the Redbarn Early American house, or the fact that he’s there to enjoy it. Between public appearances for the studio and locationing for pictures, he estimates that he’s away a good half of the time.

Both he and Pam have adjusted themselves to the fact that his absences are a necessary part of his work. As usual, the Irish in Audie is equal to the situation. To the studio’s claim that not only the public, but also the exhibitors, love to see him, Audie says, “Sure the exhibitors love me; I’m a two-bag man! By the time I’m through shooting up all the villains, the audience has gone through two bags of popcorn each.”

Although they haven’t finished furnishing the house yet, it is assuming the air of a home that is lived in. Audie says ruefully, “All I know about furniture is that it costs money.” He leaves that part of it to Pam, just nodding agreement to her own tastes.

Typically, Audie is more concerned with the outside than the inside. Like the matter of Murphy’s Chinese Driveway. Being unpaved, the driveway became a mudhole every time it rained. Audie decided to cement it. The neighbor across the street had the cement mixings, plus a wheelbarrow. It seemed simple. “It’ll take me an hour,” Audie estimated. It took four. Finally, when the walk was laid out, Audie had to rush to get to a horse show.

On the way, he suddenly remembered something. He had meant to put the baby’s footprints in the cement! He stopped to phone Pam. Terry’s footprints were firmly imprinted—just as the stars’ are in the forecourt of the famous Grauman’s Chinese Theatre. Audie may be Hollywood’s least typical movie star. But it’s typical of his sense of humor that instead of Grauman’s he has Murphy’s Chinese Driveway right in front of his own home.

On the joys of becoming a home owner, Audie says, “The more I look, the more I see to do.” The nice, deep back yard has a redwood fence around it. But about fifty feet of the property is outside the fence. He’s looking forward to a breathing spell when he can enclose that, too. Then it will be a perfect spot for Terry and the Weimaraner, who is just two months older, to share and grow up in. Weimaraners are a rare and highly developed breed of German dog. It happens to be John Huston’s hobby to breed them in this country, and he presented Audie with a pup after they made “Red Badge of Courage.” Audie has never been without dogs in his life, even if he never owned a genuine Weimaraner before. You might call this one a sophisticated version of the hounds he hunted with in Texas. Besides boy and dog in that back-yard annex, Audie is also planning to plant a few lemon trees.

All that may have to wait a while. But mowing the front lawn, which is sizable, is a weekly chore for Audie. While he’s away, he has a deal with a gardener to take over, but only for the lawn. “At least,” he says, “if the back yard has to wait for me, nobody sees it till I can get to it.”

Terry, toddling along, really tries to help with the mowing. And when the newsboy tosses the daily paper on the lawn Audie says, “Will you pick up the paper and take it in to Mother?” He does, then comes back with a look that says he is very pleased with himself.

You’d think, with the time Audie spends away from home, that a baby might feel his daddy is a sort of stranger. It works out exactly to the contrary. There seems to be a bond between those two that encloses just the two of them. Terry, being a friendly fellow, will let anyone hold him. But let Audie come by, and he’ll squirm right off your lap on his sturdy legs to reach him. What’s more, he has reddish hair and blue eyes that promise to take on the determined grey glint of Audie’s.

While on his last personal appearance tour—the one he returned from to find Terry waiting, if asleep, at the airport—Audie called home every other night. Once, Pam decided to put Terry on the phone. First he said into the mouthpiece, “Da-da-da-da-da?” and then, from force of habit, “Cookies?” He knew the voice was coming from the phone, but even after Audie hung up he would cock his head to listen, then look all around the room to wonder where, actually, he might be hiding.

Although Terry stayed up past his bedtime the night Audie returned, he resumed the regular schedule next morning right on time. At 7:30 A.M. sharp, there he was standing by the bed. He doesn’t wake Audie by shouting or calling; he just pats him on the cheek until he opens his eyes. Then they turn on the radio, to get the news and some music, to which Terry keeps time with his feet and his fists.

In the kitchen, right after he’s had his orange juice and cereal, Terry proves that he is a chip off the old block. He disdains crying, but if he doesn’t get outdoors fast enough, he starts to fret, pouting out of the kitchen window in no uncertain terms.

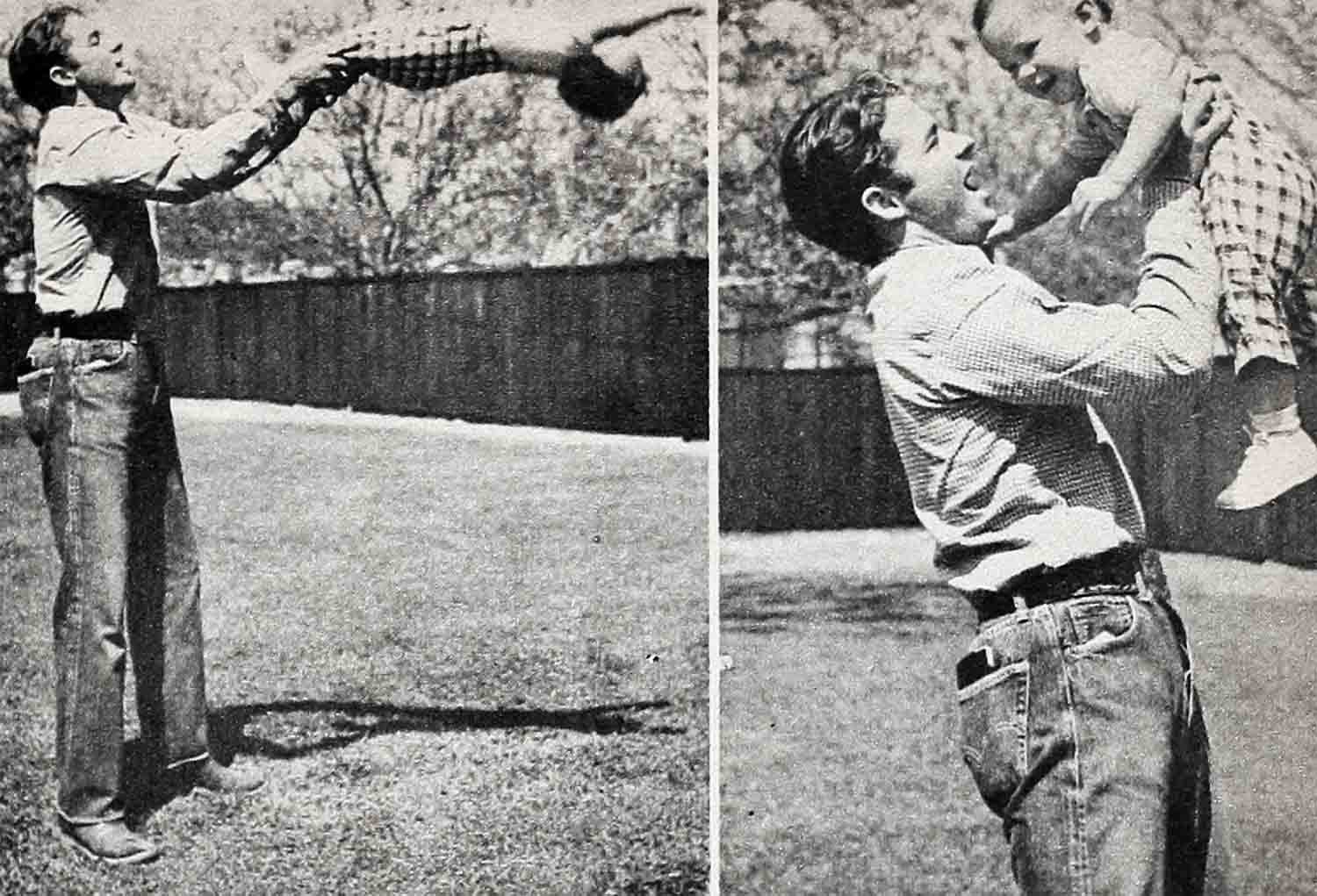

The male palship between these two naturally calls for doing stunts together. At a very early age, Terry would squeal delightedly while Audie swung him by the heels. At the more advanced age of four months, he just hung on with two fingers for more of the same. Lately, he’s graduated to a more daredevil stunt. He likes to stand on the mantel and jump into Audie’s arms.

But there’s no leaping before he looks for Terry. “A hambone already,” chides Audie. “Likes an audience. And he makes sure anybody who might be in the room is looking before he jumps.” But it’s possible that it’s Audie who gets the biggest wham out of their newest stunt—horseback riding. “I just put him on the saddle in front of me,” chuckles Audie, “and away we go.”

Naturally, Pam takes all this calmly. At least, she has learned to hide the impulse to hold her breath while all this man stuff goes on.

Audie’s viewpoint is, “Children make a nicer person out of you. Anyway, it works out that way for me.” On the other hand, there is something in Audie that children and animals respond to. He explains, “I treat them as equals.”

Audie’s horse, who is two years old, makes his home mostly on the back lot at Universal-International. “I’d like him to be in pictures with me,” says Audie, “but I don’t think he’s quite ready.” So in his current Technicolor Western at the studio, “Tumbleweeds,” Audie is riding what he describes as an old Indian pony called Lightning, the same pony he rides in “Column South.”

Audie says, “It’s hard to find a good name for an animal,” so he hasn’t registered either dog or horse yet. So far, the horse has been “Flying John.” He’d like to call the Weimaraner “Long John”—after Long John Huston. With the dog’s Teutonic antecedents, it has occurred to Audie that translating it into “Langer Johann” would make a flossy Kennel registry.

Upkeep and training of animals takes time, attention and money. Audie claims, “A woman doesn’t understand these expenditures.” Actually, he knows that Pam does understand that animals are as much a part of his life as breathing, so that’s good enough for her.

Pam has had her feet pretty firmly planted on the ground since giving up her job as hostess for Braniff Airways to marry Audie. Being from Texas herself has helped hurdle some of the problems, the first of which was settling down to being a homebody from her own pretty glamorous sky career. Then, too, it’s tough on a young marriage when the husband has to be away so much. But Audie and Pam had almost a year to get to know each other, after they met in Hollywood, before they married. It’s Pam who should be the lonesome one, but it’s Audie who sighs, “Home life? I enjoy what there is of it!”

For Pam’s part, she’s too busy keeping up with Terry Michael Murphy and running the house to brood about problems. And, as things do that are given time, everything seems to be working out just fine and dandy for the Audie Murphys.

Right now, Pam has a maid in just twice a week for the heavier work. But they’re looking ahead to building an extra bedroom for a maid. That way, there will be no problems about a baby sitter, and Pam can get out more for some social life.

“But we’re in no hurry,” says Audie. “The house is furnished enough so we don’t have to sit on apple crates any more, at least.” The den is cozy enough to keep anyone from being lonely. The living room is large enough to hold a satisfactory number of people. And there’s a full dining room—which was Audie’s major specification concerning a house. “A breakfast nook,” he says, “is fine for breakfast. It’s even all right for dinner for just the two of us. But if there is anyone else, I want to sit down at the table in a regular dining room.”

The truth is that Audie and Pam are living their personal life as if they were citizens of maybe Great Falls, Montana—one of the stops on Audie’s recent tour—or even of Kingston, Texas, where Audie was born.

But if the Murphys have managed to stay off the Hollywood social circuit, the Hollywood limelight has at times caught up with them. At first, when Audie would make an appearance at a studio party by himself, eyebrows went up. By now, that’s not a juicy question mark any more. People know they couldn’t get a baby sitter, and Pam had to stay home.

Of the two, Pam is, in fact, the more gregarious. She likes to go out and mingle with people, even if Audie’s idea of recreation is fishing, hunting—anything, so long as it’s outdoors. But if Pam sometimes has to baby sit while Audie makes a necessary public appearance, turnabout is only fair play. He takes his turn at baby sitting when Pam gets that gleam in her eye that means she hasn’t seen a movie in too long.

The Murphys have been too busy getting their home life set up on an even keel to have acquired a Hollywood social life. To Audie, “friends” aren’t people you know casually, but people who mean something to you. He has friends whom he goes hunting with in Bakersfield, a short drive from Hollywood. Both he and Pam have many old friends back in Texas. And with Audie’s three sisters and two brothers there, they are looking forward to taking Terry “home” to introduce him to the fact that he’s unofficially a Texan. Terry actually is named for Audie’s closest friend, Hollywood’s famous physical culturist, Terry Hunt.

Audie Murphy was twenty-nine on June 20. In looks, he seems younger; but he has an inner dignity that gives him the poise of someone who has lived much longer. In many ways, he has already lived a great deal more than many men do in a lifetime; and he has achieved the distinctions that have come to him on his own.

Certainly, there was nothing in his background to indicate when he lived with his sister in Farmersville, Texas, that he would become famous as a double celebrity—both a war and a movie hero.

When he left his home town for a movie offer from Bill Cagney, there were some who threw up their hands and asked, “What will Hollywood do to that boy?”

That question has been answered. Audie has proved he’s able to take care of himself on the cinema battlefield, too. And others get a pretty solid feeling around him. It’s something like the way they felt about him in the Army.

“When Murph had his men in the front lines,” one comrade-in-arms states, “we in the rear felt it was safe to go to sleep!”

THE END

—BY HELEN GOULD

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE AUGUST 1953

No Comments