Roy Rogers’s Ranch

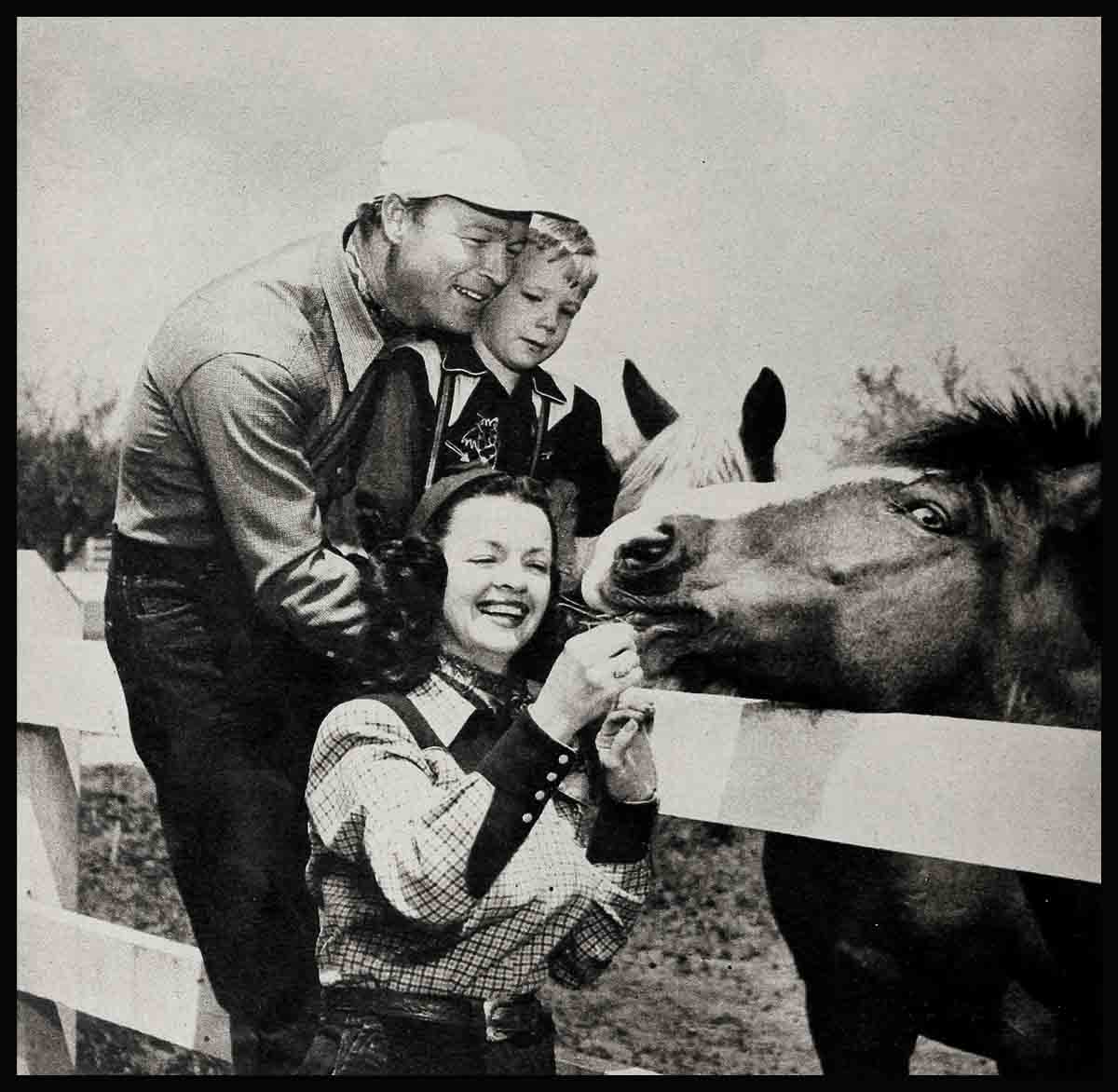

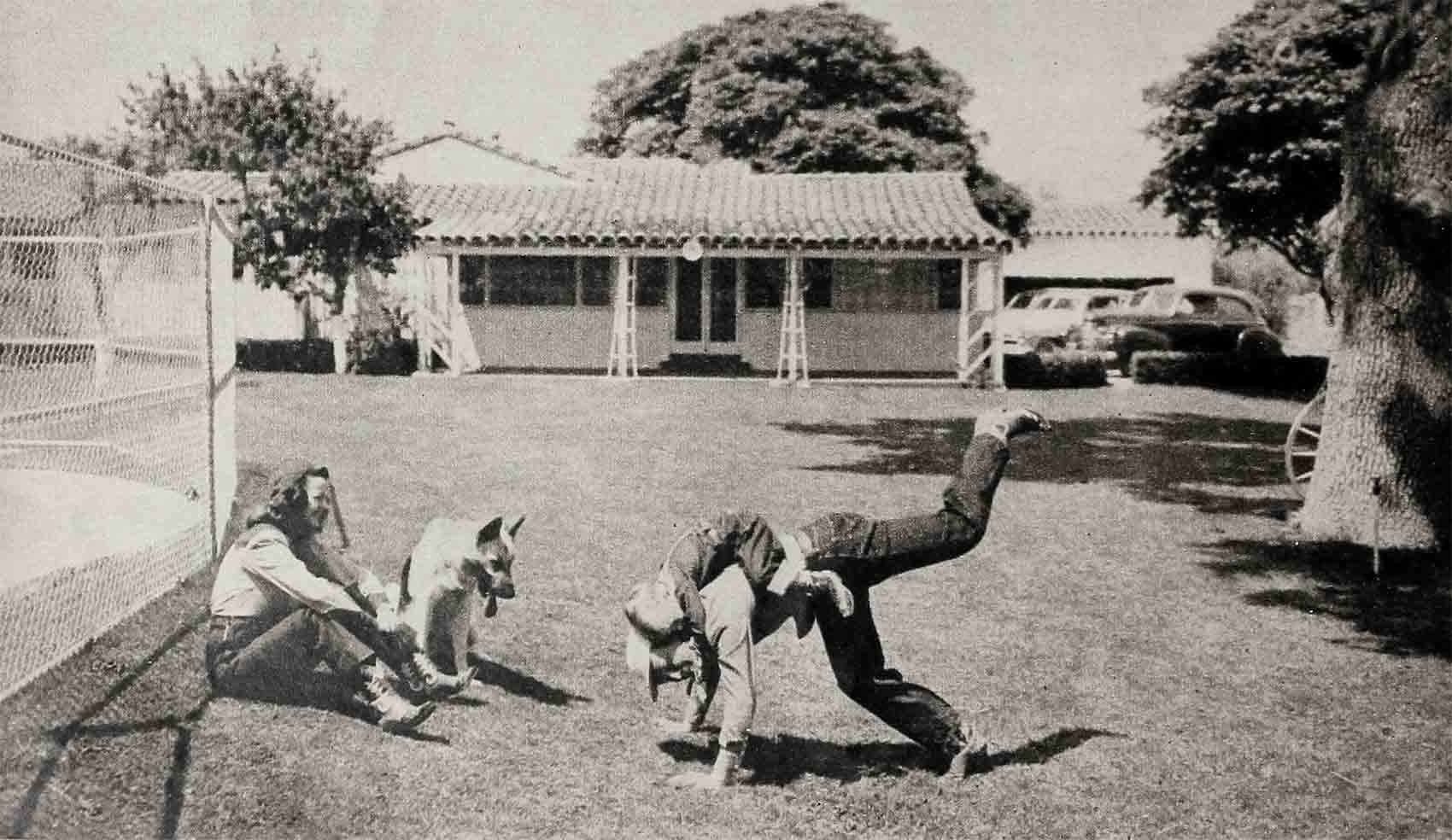

Roy Rogers is an animal-lover. When he acts with a squirrel in a picture, he brings the squirrel home. When he acts with a possum, he brings the possum home. A few weeks ago, Roy strode into his ranch-house with a beautiful German Shepherd named Bullet who plays opposite him in Pals of the Golden West.

“I felt,” Roy says, “that if Bullet lived with me a little, both of us would develop a closer working relationship—like the relationship I have with Trigger.”

The first night the dog stayed at the ranch, five-year-old Junior, better known as Dusty, began calling his father. “Hey, Dad,” he shouted. “Come here and see what Bullet is doing.”

“In a minute, Son,” Roy answered from his small home office.

“You’d better hurry!” Dusty yelled.

“Take it easy,” Roy said.

“Okay,” Dusty agreed. “Only he’s chewing your best hat to pieces.”

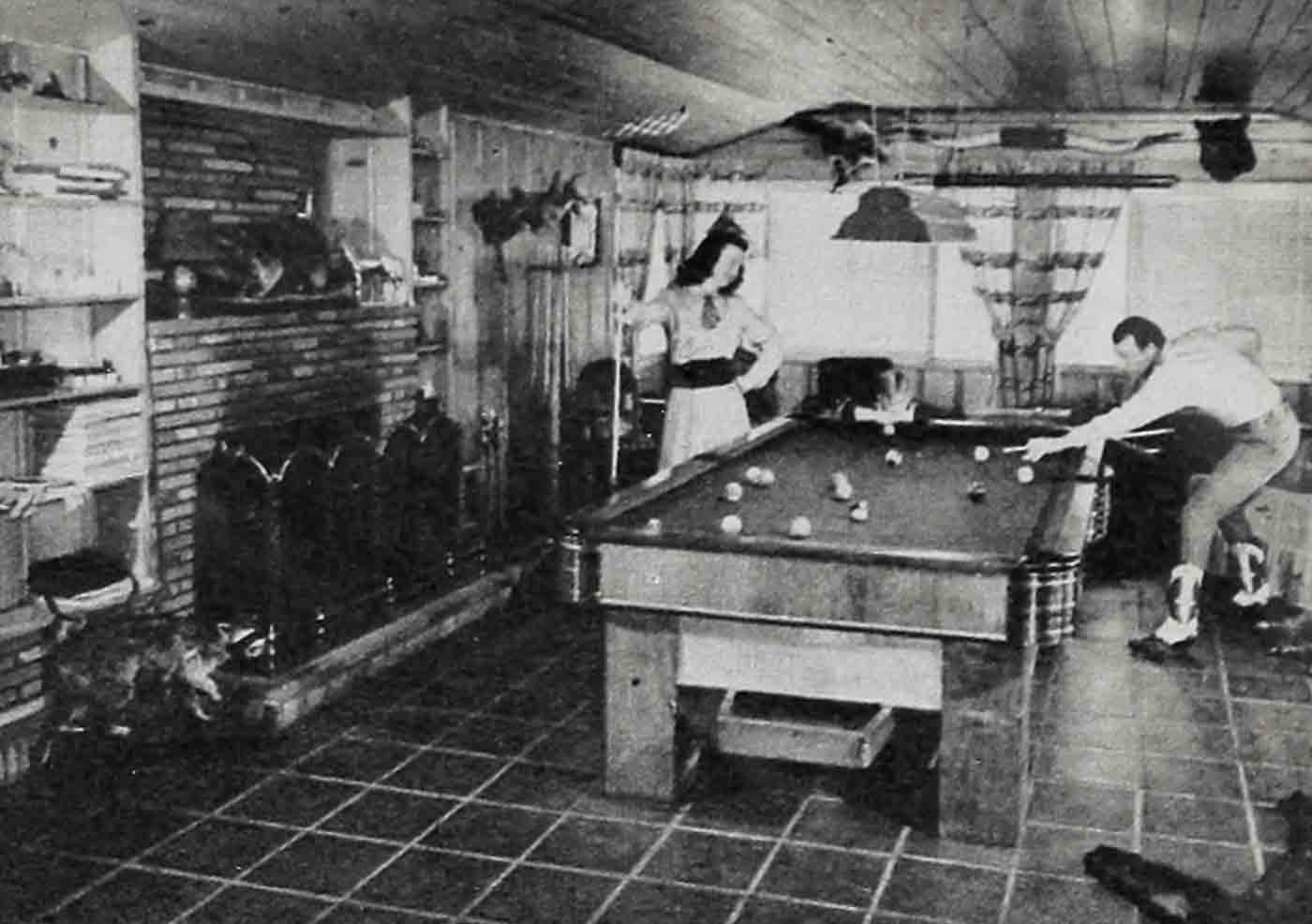

Roy was on his feet in a flash. Two more seconds, and he was in the billiard room where Bullet was finding a cowboy hat tough to digest. One sharp Roy Rogers command, and Bullet dropped what was left of the hat at Roy’s feet and waited patiently for a pat of praise. There was no praise. Neither was their punishment. Roy knew that the dog was unfamiliar with his surroundings.

“Bullet’s gonna have to learn about hats,” he announced, “if he wants to stay here. Come on, Dusty, let’s show him around.”

A stroll around the Roy Rogers estate, five acres in the San Fernando Valley, is a tour of four separate houses.

The main building, a low-slung, irregularly-shaped Spanish ranch-house, has five bedrooms, an office, a billiard room (shooting pool is not a talent exclusively reserved to city slickers), a living room, a dining room, and a kitchen in perennial use.

Out back, five running steps from the kitchen door, is the baby’s quarters. Robin Rogers was born 10 months ago. She came into the world with a congenitally weak heart and needs rest and extreme quiet so that she can grow without straining it.

The doctors suggested that Robin be kept in the hospital or in a special nursing home, but Roy and Dale wouldn’t hear of it. They wanted their baby at home.

Even though it meant added expense, another $10,000 to be exact, they constructed a private clinic for Robin and her nurse on their own property.

“I just had to have her near me,” Dale says. “I knew I couldn’t have her in the main house. After all, we have three other children, it wouldn’t have been fair to them—shushing them all the time. So we built a little house for Robin. While she’s sleeping, Roy and I tiptoe in and look at her. We pray that in the years to come her heart will grow stronger, so that she can play freely with the others and even use the swimming pool.”

Next to the Rogers’ swimming pool are some dressing rooms, a large outdoor barbecue, and a food locker which Roy insists, “I couldn’t live without.”

Whenever he and Dale aren’t working in pictures or making personal appearance tours, they like to hunt. They take their dogs, go up into the mountains, and come back with a load of rabbit, pheasant, wood ducks, deer, and occasionally even a bear or two. The edible game is preserved in an 18-foot Amana freezer. It’s an upright job. “That’s the best kind of freezer,” Dale says. “You don’t have to break your back bending down to get out a carton of peas.”

Actually, the home the Roy Rogers family currently occupies isn’t the house Roy likes best. “This one is a compromise, Dale explains. “It’s as rural as we can make it and still act in motion pictures. If Roy had his way, we’d live on a real working ranch and fly down to the studio every morning.

As a matter of fact, we do co-own a real ranch near Marysville, California. Roy has a partner and they raise wonderful cattle, white-faced Herefords. Whenever we can arrange it, we try to spend a weekend up there. But between weekends, we stay down here in the Valley where Roy raises as many animals as the zoning laws permit. He keeps two horses, a pony for the children, 150 chickens, half-a-dozen dogs and cats, a possum, and four squirrels. That’s as of right now. Tonight, it might be different. He’s liable to come home with two or three rabbits.

“Roy was born in Cincinnati, you know, but as a child he was raised on a farm in Duck Run, Ohio, and he can’t get the animals or earth out of his blood.”

To prove her point, Dale is always taking friends out to the land behind the tennis court to show them Roy’s “Farm.” It consists of a back lot planted with vegetables and a border of fruit trees.

Roy and Dale have a system. She credits him with the outdoor beauty of their home, and he credits her with the interior. “She’s fixed our place up real swell,” Roy says, “and without spending a fortune.”

“When we moved into this house six months ago,” Dale points out, “I used as much of our old furniture as possible. No sense in letting that go to waste.”

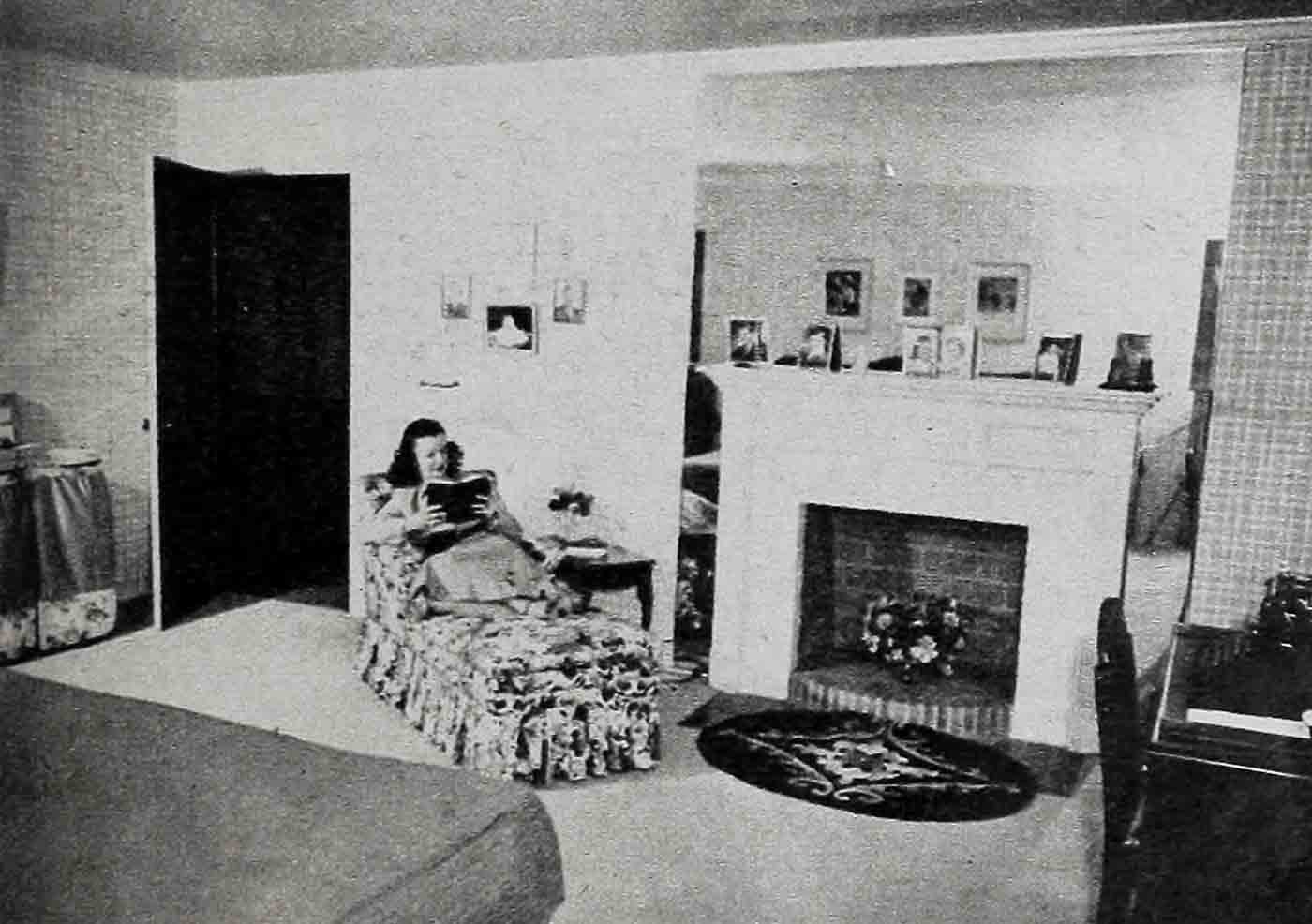

For her blue-green living room, Dale did buy a new swirl-pattern carpet, new draperies, and two sectional pieces. She placed the chairs by the fireplace, a fine seating arrangement for the family, but when friends drop in, the fireplace grouping is expanded to include a sofa and two upholstered day beds placed end to end.

The remainder of the furnishings in the room—the spinet piano, the hearth rug, the blond coffee table, the two floor lamps, and the painting of Roy by Evan Soward are all part of their former house.

Roy insists that Dale knows some cute decorating tricks. The lamps on the spinet piano are samples of her handiwork. These had ordinary glass shades until Dale saw some hand-painted ones in an antique store. She went home, cut out some cowboy figures from a wall-paper sample and pasted them on her old lamp shades. The effect is the same as the the hand-painted variety, only much less costly.

As in the other rooms, most of the furniture in the Rogers’ master bedroom comes from their previous home. The kingsize bed, the dressing table, the chaise, and the desk are all pieces they’ve owned since their marriage in 1947. Only the wall paper is new. “I couldn’t very well take that with me,” Dale says jokingly. “But in selecting the new bedroom paper, I chose a green and beige plaid because the color combination reminded me of one of Roy’s shirts.”

A bathroom separates it from the bedroom, but Roy’s office is almost part of the master suite. Roy works here surrounded by a life-size portrait of Trigger, a dozen plaques naming him the Western star of the year, and his own Philco television set.

Roy makes an honest effort to answer all his fan mail. He sends out autographed photos and acknowledges gifts as he receives them. When the job gets too much for him, he presses Dale into service. She keeps the typewriter she’s had from her secretarial days ready and open on her own bedroom desk, and whenever Roy cries for help, she sprints into his office, shorthand book in hand.

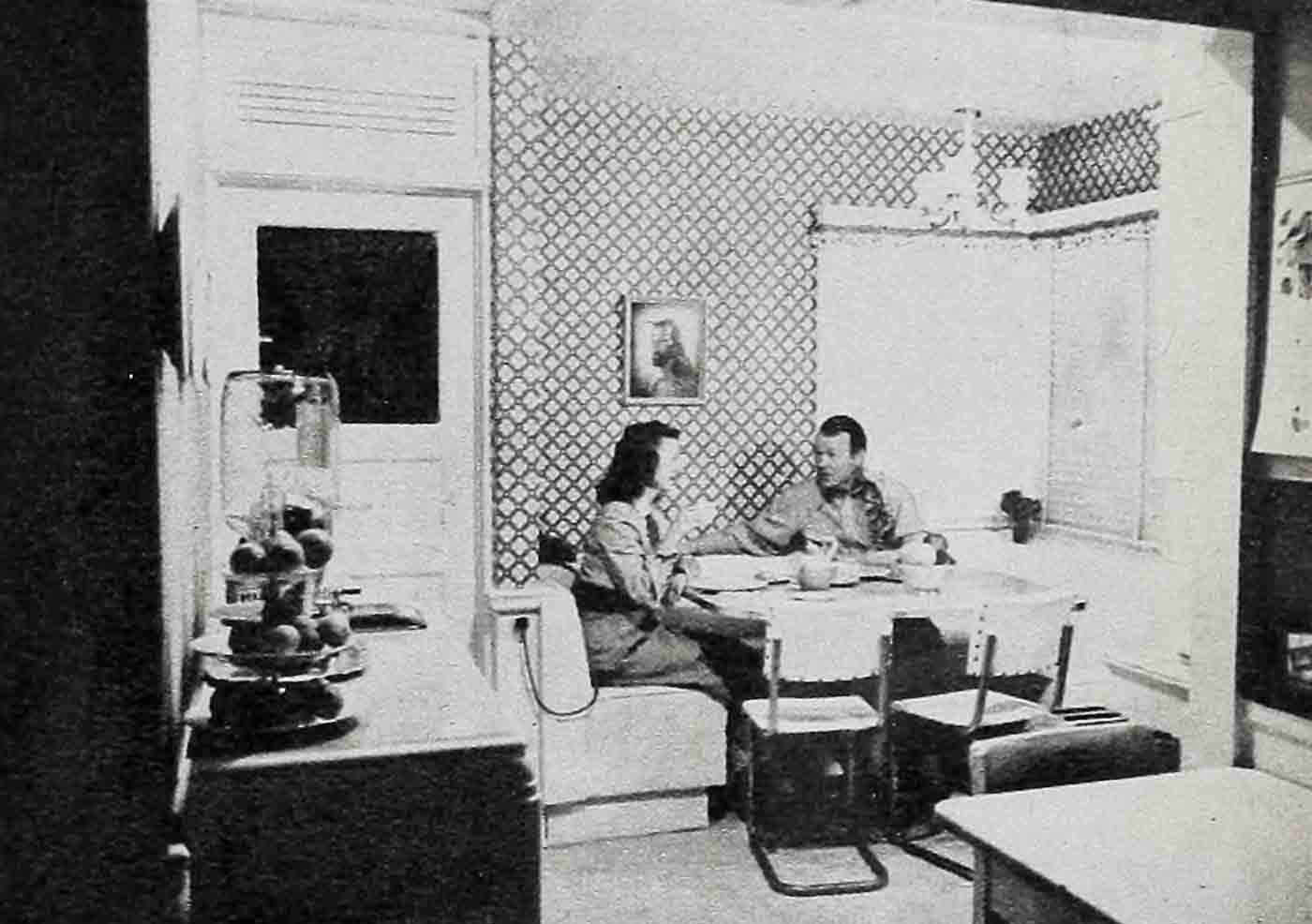

The Rogers have one standing rule in their house. Everyone must be home for six-thirty dinner. Guilty persons are put in the doghouse. A miniature doghouse stands on the kitchen wall. It contains five tags with the names of the various family members. The only way to get your name out of the doghouse is to help Emily with the dishes, or some other household chore.

Dale and Roy both feel that this is an important rule because it brings the whole family together at least once a day. “It gives the children a feeling of family solidarity,” Roy says, “which is pretty necessary these days when just about every other solidarity is shaking.”

Every Sunday, the entire Rogers household attends the St. Nicholas Episcopal Church in Encino.

Sunday night also finds them eating around the circular dining-room table. All other meals, however, are served practically continuously in the kitchen-breakfast nook. This leather-upholstered corner had to be added to the kitchen to satisfy the lusty appetites of Cheryl, eleven, Linda Lou, nine, and Dusty, five.

“Those kids eat all the time,” Emily Warren, the cook, says, “but I like that. I also like them to bring their friends. The nook looks small but it can really seat eight quite comfortably.”

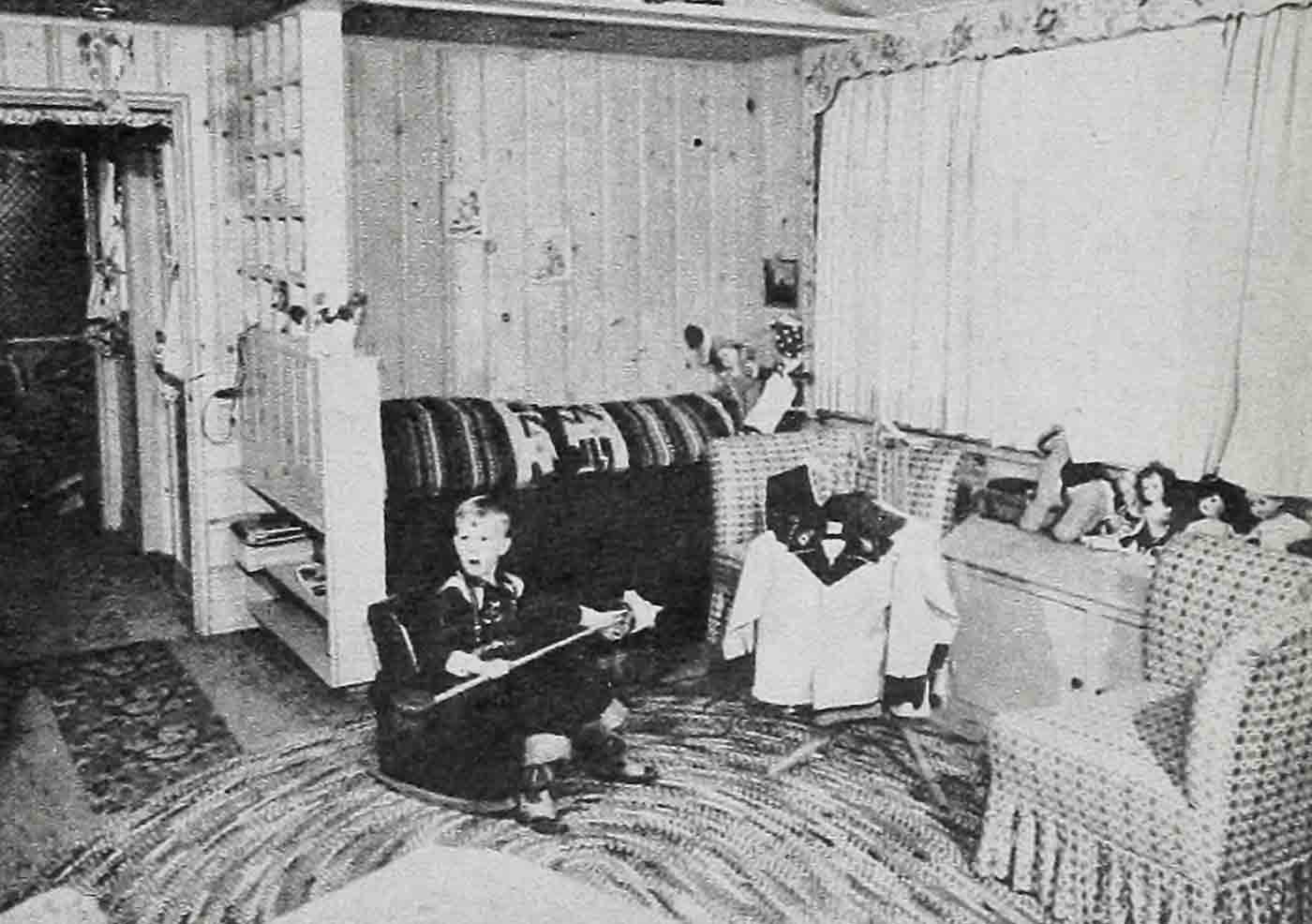

The children’s section of the Rogers house is next to the kitchen. Known as the children’s wing, it consists of three separate bedrooms which open onto one large playroom. The wing has its own bathroom and a separate entrance, and the little guys can raise hallelujah while the rest of the household moves at a quiet pace.

The room Roy himself likes best is the billiard room. Pine-panelled, tiled-in-red, it boasts a friendly fireplace, a three-way exposure to the valley, a billiard table, twelve shelves of books, a 16 mm. sound projector, and dozens of hunting trophies. The maps and ash trays are gifts from admirers; a pair of Roy’s boots which stand by the door, are cast in bronze. All the furnishings are typically masculine and designed to please the master of the house.

At night, after the children go to bed, Roy and Dale usually come into this room to discuss family problems, the day’s work or just to chat the way married folks usually do.

Only the other night, Dale was recounting an amusing anecdote. Coming out of the studio, she heard a little boy say to his brother, “There’s Dale Evans.” “That isn’t Dale Evans,” the brother said.

“Oh, yes, it is,” repeated the first little shaver. “I recognized her at once. Her hair is the exact same color as Trigger’s.”

THE END

—BY MARVA PETERSON

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE SEPTEMBER 1951