The Longest Night Of My Life—Ruth Roman

I clung to the Jacob’s ladder dangling down from the Andrea Doria, half way between the deck and the water, and watched the lifeboat with my son in it pull away from me, into the fog. The last I saw of his little face, he wasn’t crying. He had climbed into the lap of an Italian woman I had met on board the ship, and he was holding tight to his red balloon. Then the boat disappeared, and there was nothing for me to do but hang on, and pray.

It had begun as such a nice evening. It was terribly foggy out, but no one cared. We were only one day away from New York, and there was a dance being given. Dickie—he’s three and a half—was asleep in the cabin, with his nurse. At 11:30 my friend Janet Stewart and I were up on the top deck, in the Belvedere Lounge. Everyone was singing—it was very gay. All of a sudden—the crash came. For a second I was stunned. I’ve been in an avalanche, I’ve been in accidents. Always at first there’s the moment of complete shock, when nothing happens. Then suddenly you snap out of it. The Andrea rolled terribly and began to settle at a terrific list. I thought, “We’ve been torpedoed!” All of a sudden I started moving. Deep inside myself I was numb, I was praying. On the outside, I was doing the things I had to do. Don’t ask me how. That’s a question no one can answer.

I kicked off my shoes. “Don’t get excited,” I called to Janet. “I’m going for Dickie.” Without shoes it was possible to walk on that tilted sliding-board of a deck. With shoes, I’d have had to crawl. I made it downstairs to the cabin in about three seconds. I threw open the door. Without turning on the lights I could see Miss Els, the nurse. Her lip was cut and bleeding; she’d been thrown against something. She still wasn’t fully awake. Dickie was groggy with sleep. I plunged into the room and grabbed life preservers and blankets. “Get Dickie, let’s go!” I shouted to Miss Els. Then I turned to my baby. “We’re going on a picnic,” I said.

I led the way out to the boat deck. We were on the starboard side. When I was a little girl I took ballet lessons. Somehow the mind goes back through a life and picks out what it needs. I remembered what I had learned in one of those lessons. If you lie down and put your arms above your head, and try to relax your body, you will relax. I made Miss Els and Dickie lie down and I lay alongside them. Dickie was excited at being up so late, all the people around him. I call him “My Mouse,” but he isn’t a shy little boy. He loves people. When they were all right I got up again, to go further out on the deck and look for lights. All around me people were sitting, sliding. Most of them seemed still numb. Up ahead a lady had fallen overboard and a sailor had jumped into the sea after her. I remember thinking, “What a brave man.” There were no lights. Some one told me we had crashed into the Swedish liner, the Stockholm.

The ship was listing but I wasn’t frightened. Isn’t that strange? I think it was because I had nothing to be frightened about. I had all my things with me on the ship—jewelry, furs, everything I owned. I never thought of them once until days later. For myself, I wasn’t afraid. I love boats; my former husband and I had our own, and the sea is not foreign to me. But mostly I was not afraid because, for the moment at least, Dickie was all right. Dickie is my first baby, my only one. I never had him in danger before. I don’t think that at such a time any mother in the world ever thought of herself. And right now, Dickie was all right. I turned and hurried back to him.

A red balloon

On the way back, clinging to rails, watching my footing every inch, I saw a red balloon lying on the deck, deflated. I picked it up and blew it up. I brought it to Dickie, put it into his delighted hands, and lay down beside him. I put my arms up and tried to relax. I thought, “If anything happens suddenly, I’ll need every bit of strength.”

All around me people were helping each other. When it was all over I heard the stories about panic, complaints about the crew. But in our little space on that fogbound deck, I saw no panic, nothing but kindness and heroism. Under the blanket, wrapped in his life preserver, Dickie was warm and cosy; he had his balloon to play with. But he wasn’t used to being up at that hour; he was hungry. From out of nowhere Bruno, our steward, appeared with milk for him. How he got it, or where, I’ll never know. An old gentleman stretched out beside us. “The best thing to do is relax,” he said. Across from me I could see the leader of the little orchestra on the ship scurrying around, working his way from person to person, helping with lifebelts, making people comfortable. He couldn’t do enough for people.

For an hour we lay there. What went on in my mind then? When I was a little girl I was taught to pray every night. I don’t do that so regularly any more. I don’t attend religious services. But whenever I see someone disabled, someone in need of help, inside I pray. Without prayer Id be lost; it’s like eating or drinking to me—that natural. Prayer is the way I preserve myself in times of trouble; it is what keeps my feet on the ground. Underneath the part of my mind that was planning for what might happen, I prayed.

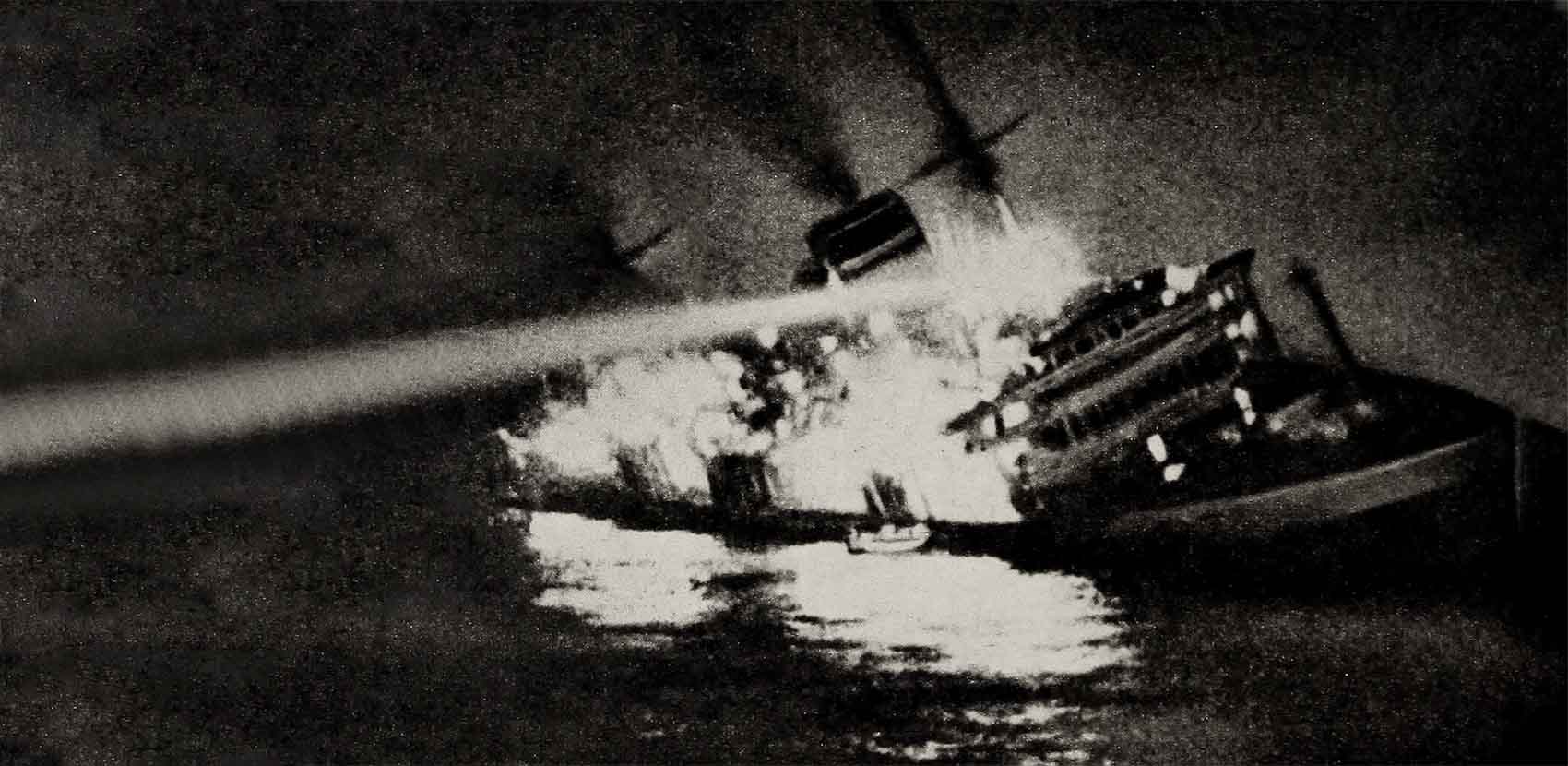

Because of the terrible angle of the ship, all the boats on one side were useless: it was impossible to lower them. On the other side of the deck, they had some. Somebody told me there were other boats coming for us; no one knew which, or where they were exactly. The list was getting worse. I thought, “We’d better get to the boats now.”

I was wearing a sheath dress. I ripped it up the back, and sat Dickie down between my legs. Then I pushed us off and we slid down the deck to the boats. Now I think it must have been an amusing sight, the two of us, Miss Els, dozens of others in evening clothes and pajamas, scooting across the deck as if we were sliding down a ’chute at some gigantic playground. But at the time we didn’t think how funny we looked. It was the only thing to do.

We got to the boats and stood up and got in line. A sailor took Dickie from me and tied him to himself. Underneath us I could see a lifeboat, almost filled with people, watching us, their faces upturned. The sailor swung over the side with my baby, and clambered down the ladder. I didn’t know I was supposed to wait to be roped to someone, too. I started down after him. When I was halfway down, the boat pulled away; it was full. I didn’t know where it was going. Mrs. Fantana the nice Italian lady I’d met a few days before and her little girl were on it. I saw her reach for Dickie and take him on her lap. Even at that moment I thought, “Thank God. She’ll take care of him.”

Five minutes later another lifeboat rowed towards us out of the fog and stopped beneath me. I climbed down into it. Miss Els, Janet, and some other people from the Doria followed me down; as soon as we were full we pulled away. Dickie’s boat was nowhere to be seen.

The rescue boats came slowly, lost in the fog, hunting for us. The water around us was alive with men. Sailors who had been burned. We pulled as many as we could on board and tried to help them. They were in dreadful pain. Miss Els, sitting next to me, leaned on the side of the boat. Another lifeboat swung beside us, crushing her arm. It was torn and bleeding badly, but she never said a word. It was like a nightmare.

And then, suddenly, a miracle happened. The fog lifted. Above us, where there had been nothing before, the moon shone out—huge and golden. And ahead of us, before our eyes, the most beautiful sight I have ever seen—a huge ship, blazing with light, every window a glowing, glorious, blazing light. Spelled out on her side in tremendous shining lights was written: Ile de France.

Blankets and soup to warm us

She took us in like a mother welcoming her children home. Arms reached out to help us onto the deck. Almost before we had both feet off the ladder we were wrapped in blankets with cups of steaming bouillon in our hands. Before we could take a sip, the boat that had brought us to safety had turned and gone back to the dying Doria.

Someone bandaged poor Miss Els’s arm, and she, Janet and I, started looking for Dickie. We went from deck to deck, asking for him. “Have you seen a little boy with a red balloon?” Nobody had seen him. Nobody had seen Mrs. Fantana or her daughter. Every now and then we went back to the deck where, all through that night, the Ile had coffee and food and soup for the survivors. But no one had seen Dickie.

At first I couldn’t believe it. He had to be there, somewhere, on the ship. Then they told me there were eight rescue ships at the Doria. The boat he was taken on could have belonged to any of them. A very kind man who I later learned was Eddie Hand, was on the Ile. He took us to his stateroom. “Dickie’s not on the ship,” he told me, “but he’s on one of the others. He’s O.K.”

“I have to know which one,” I said. “Can we radio?”

Eddie went to find out. “No,” he said when he came back. “They might have to radio all eight to find out. In this confusion, no one would know. And the radios are all tied up. He’s all right, Ruth. You saw him in the lifeboat.”

I knew he was right. I knew he was safe. I knew Mrs. Fantana would take good care of him. But—

“Will he be frightened?” Eddie asked.

I thought of Dickie, his wide eyes glowing with friendliness, his interest in everything going on around him. “No,” I said. “I don’t think so.”

Eddie gives us clothes

I felt much better. Eddie was wonderful. He gave us his clothes, shirts, socks, pants, and disappeared while we got dressed. I pulled my ripped sheath off. I put on a soft t-shirt. Eddie’s pants came practically up to my chest. I rolled up the bottoms and tied the top around my waist with a piece of cord. His heavy thick socks were warm on my feet. I flapped around in that outfit until the Ile de France, which had turned back from its route to Europe to bring us home, pulled into New York. Photographers took pictures of me looking like a scarecrow. I didn’t care.

We walked down the gangplank and there were friends, and people’s relatives waiting, looking for the people they loved. Mary Kelly, a wonderful girl who works for NBC, was there. And other friends. I asked everyone, “Has anyone heard about Dickie?” No one had. I told reporters, “I believe he is safe.” I meant it. I did believe it. But I wanted to know.

Mary swept me into a taxi and took me to the Warwick. NBC had made a reservation for me. They had clothes for me. They were wonderful. I asked Mary, “After all this—can you make contact with the Stockholm?Somebody said he might be on the Stockholm.”

“We can even do that,” Mary said. She put in a shore to ship phone call to the Coast Guard Cutter that was bringing the limping Stockholm into port. In half an hour I knew. Dickie was on it.

The last danger

On July 27, one day after the Ile brought me back, the Stockholm was due in at Pier 97 on the Hudson River. There was a crowd of people waiting, as I was waiting. I stood at the far end of the dock. The Stockholm pulled into sight; her bow was completely destroyed by the collision. It was a fearful sight. All night I had known the danger wasn’t over yet, listening to the radio. The Stockholm was on shaky legs. We had heard it was possible that she might also sink. She came into view and all of us on the dock gasped, watching. Surely she couldn’t make another mile, surely she would go down and it would all begin again.

But she made it into port. I didn’t know it but I guess I had been crying. I looked and looked but I couldn’t see Dickie. Then on the lower deck at the rails I saw some people I knew from the Doria—Italian people, but not Mrs. Fantana. I shouted to them and they saw me. I called, “Mia bambino-”

They pointed up. “Supra!” they shouted.

I looked up, up, to the top deck. I saw Dickie.

Mrs. Fantana was holding him. I jumped up and down and waved. There were tears pouring down my face. “Dickie, Dickie, Dickie,” I called.

He saw me. He hollered, “Mommy!”

Then he called, “How is Elsie?”

I was having a conversation with my son. “She’s fine,” I shouted. Then I called out, “Dickie, where’s your red balloon?”

“It popped!” he shrieked. I began to laugh. My son was coming home to me. We had been shipwrecked at sea, separated,—and I was asking him about balloons. I went. on laughing and I went on crying.

I hold my Mouse again

Mrs. Fantana carried him off the ship, leading her little girl by the hand. She came down the gangplank and we couldn’t get to each other. There were crowds and there was a long wooden barrier. On one side of the barrier, she walked towards the opening. On the other side I ran. I waited for them with my arms stretched out. And then I held Dickie again.

I tried to thank Mrs. Fantana. She wouldn’t let me. “He was fine,” she told me. “He kept asking for you, but I said we would see you in a little while, and he was good.”

I looked at my baby. He had on a pair of blue shorts I had never seen before. He was wearing somebody’s little white shirt, with lace on it. He looked like Little Lord Fauntleroy.

“How are you,” I kept asking him.

“I’m fine,” he said. “I had a wonderful trip.” He looked at me gravely. “Mommy,” he said, “You know the Andrea Doria went down with all my cars on it?”

“I know, Mouse,” I said. “I’ll get you some more.” And my baby and I started for home.

THE END

—BY RUTH ROMAN

Ruth Roman can currently be seen in RKO’s Great Day In The Morning.

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE NOVEMBER 1956