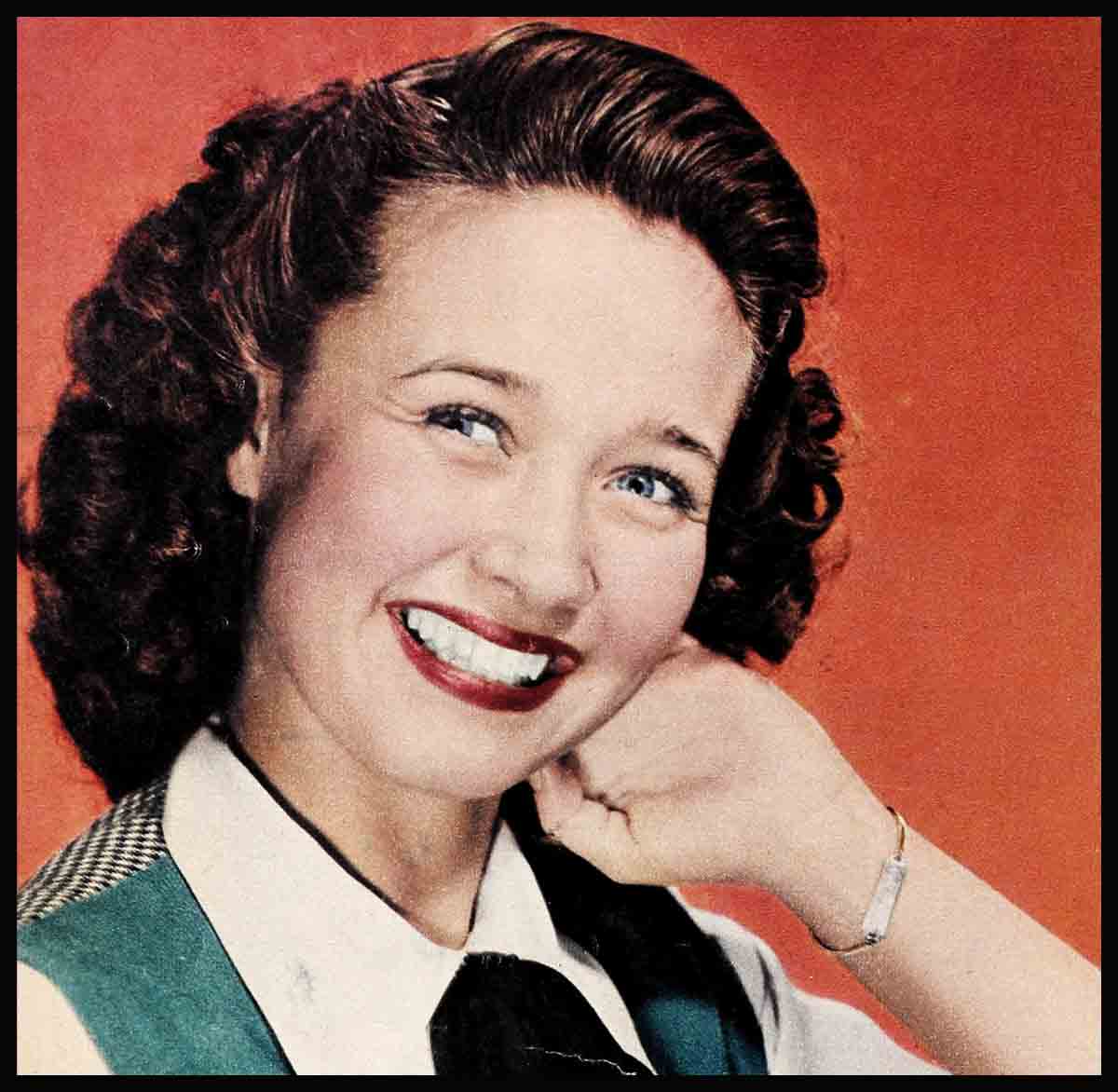

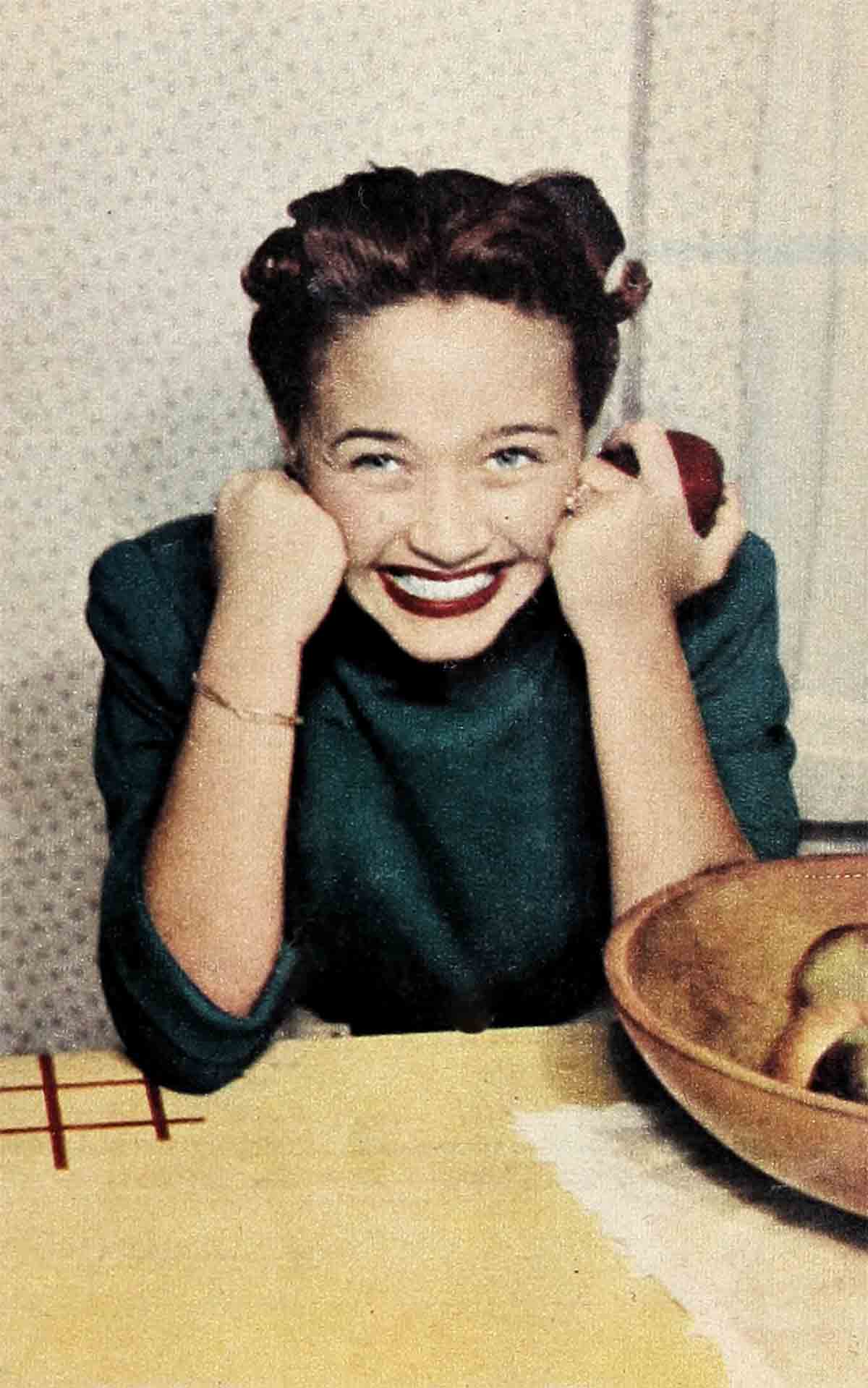

Little Miss Portland—Jane Powell

It was the annual outdoor picnic at Sawtelle Government Hospital. Veterans sat on chairs on the lawn, their scars of wars forgotten, as they watched the program being given on the wooden platform before them.

Suddenly the sun went behind a cloud and it began to rain. Some of the men ran for nearby trees to take cover. Then, as though drawn by a magnet, all returned to their seats. A little girl in a shiny blue metallic dress was up there singing her heart out in the rain. Her clear voice rang out gaily . . . “Come, come, I love you only. . . .”

One of the veterans got an umbrella and held it over her. Another got one for the accompanist. As she finished on a high sweet note, the rain stopped abruptly and the sun shone. There was quiet. Then the thunder of applause.

As the girl stepped down from the platform, an elderly veteran put his hand on her shoulder and said in a moved voice, “You see, Jane Powell, all you have to do is sing and the sun comes out.”

Many of the others didn’t even know her. Their tribute wasn’t for Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer’s sensational new singing star, but for a girl in a blue dress who reached out to them with a golden voice and a warm smile and made them feel a little happy again.

This is the story of that girl. A little girl with enormous blue eyes who didn’t mean to be a star—and doesn’t know she is one now. A simple, wholesome American girl, whose parents managed an apartment house in Portland and now run a sandwich shop in Hollywood.

She could be any teen-ager who sits starry-eyed in a movie theater. She loves to go to movies, to swim, to ice skate, ‘“and go dancing at the Cocoanut Grove. It’s a nice family place. Lots of teen-agers go there.”

Her favorite singers are Judy Garland, James Melton and Jack Smith. She buys the latest jive records, is eager on the ebop, really o-rooney. She prefers popular music and plays and sings it at home.

Most of her weight is in her voice. She’s very small, measuring five feet and weighing ninety-five pounds. Though she has a deep healthy tan, she laments, “I’m light now. I was awfully black last summer. But I’ve faded a lot.” She has brown curly hair with red glints in it, a sudden sunny smile, and very expressive blue eyes that laugh when she’s happy and look like a soulful spaniel’s when she’s sad.

Jane Powell is just as you saw her on the screen in “Holiday in Mexico.” Either super happy or super sad. She effervesces when she’s happy, but a disappointment, any small hurt, gets her as “down” as uncapped soda pop. Abruptly the bubble’s all gone. She knits or writes long letters to girl friends back in Portland and encloses autographs . . . Van Johnson’s.

Her voice coach, Arthur “Rosy” Rosenstein, compares her lyric coloratura voice with its range up to e-flat with Geraldine Farrar’s. “In all the years I’ve worked with good singers, I’ve only met two really great talents . . . Janie and Geraldine,” he says enthusiastically. “The Janie Powells come one in a million.”

Rosy, who usually refers to his famous pupil more simply as “Snooks,” admits that she s crazy about boogie-woogie and would be singing it three-fourths of the time if she could get away with it. “She sings something very difficult like ‘Depuis Le Jour,’ sings it so beautifully you could cry, with everything inside her really living it. Then the minute it’s finished, plops down to the piano and starts rumbling the bass notes around in boogie-woogie . . . and I don’t exist,” he laughs.

She’s the pride of Portland, where they’ve named the park in which they give summer concerts Jane Powell Center,” put a tablet m a tree and always call special chapel sessions at school. The girl who sings at the most star-studded affairs in Hollywood has never been able to sing in chapel before old classmates without choking up

For some reason, she’s always in the best voice when she’s singing for the opposite sex. They don’t necessarily have to be Walter Pidgeons, but it helps. “He’s always been my idol,” she says dreamily. Though shed been on the Metro lot two years, their first momentous meeting took place just before they started “Holiday in Mexmo,” when she went over to the photo still gallery to pose for some poster art with him. “I was so nervous I could hardly stand it,” she says. “I was even afraid to talk to him. So I just said ‘Hello.’ When I start making conversation, I always put my foot in it anyway. So I didn’t,” she says honestly.

The most refreshing thing about Janie is her passion for truth. She’s very outspoken and usually about 100 per cent right where-of she speaks. Which doesn’t always help. As one friend puts it mildly, “Her honesty is stronger at times than her diplomacy. It frequently gets her into warm water . . . and it takes the sunny smile and the blue eyes to pull her back out.”

She looks fifteen, for which her studio, believing she can best serve today’s youth by picturing its problems and hoping she can go on picturing them for quite some time, is duly grateful. But like any typical teen-ager who wants every solid month she has coming to her, Janie says seventeen, which is right, when anyone inquires her age, saying later, “Well, they asked me.”

A reporter visiting her home the other day asked to see Jane’s immense record collection, saying she’d read somewhere that it numbered around 5,000 recordings. “Oh . . . that’s a lie!” said Janie horrified. She pointed to a small neat stack of records over in a corner by the record player. “There they all are.”

She was born Suzanne Burce, the daughter of Paul and Eileen Burce. Her mother says Janie first started singing when she was two years old. “She sang ‘Shanty in Old Shanty Town’ all the way through. We never knew where she learned it. She could always, carry a tune.”

She made her first public appearance at the age of four in a big recital at the high-school auditorium, to which Jane, wearing a kitten costume, contributed a tap dance.

“The neighbors thought Janie could sing pretty well,” her mother goes on modestly, “and they all wanted her to take lessons.”

“In self defense,” puts in the irrepressible Janie quickly. “The neighbors said to themselves . . . ‘She has to improve. We can’t stand it! Give her lessons. . .’ ”

Jane started taking voice lessons from Mrs. Fred Olsen in Portland when she was eleven. When she was thirteen she had her own fifteen-minute show over radio station KOIN there. That summer the Burces decided to spend their vacation in Southern California. The manager of the radio station suggested that Jane try out for Janet Gaynor’s “Hollywood Showcase program. “If she makes it . . . it would help pay your expenses,” he pointed out. He sent a recording of her singing “Il Bacie” on ahead of them, and gave them a letter of introduction.

There was no thought of a motion-picture career. But an agent there at the dress rehearsal of the show raised up out of his satirical slump when Janie began to sing. He called some executives and had them listen in that night. And by noon the next day every studio in town had called the Burces’ modest hotel room.

A few days later Jane was singing “Il Bacie” for Louis B. Mayer, Producer Joseph Pasternak and eight other top M-G-M executives in Mayer’s office. After a few bars, she forgot any of them was there. She was taken away by the song. Living it. The executives, in turn, were taken away by the little girl dressed in all white who was singing so much with her heart, not making any wild gestures or trying to impress them at all. A half hour later she’d signed a contract.

The Burces went back to Portland, sold the new home they’d just built, took a last lingering look at the lawn Jane s father had set out by hand, and moved to Hollywood. Metro loaned Janie to Producer Charles Rogers for a part in “Song of the Open Road” that was built into the lead. A guest appearance on the Edgar Bergen show resulted in a thirteen-weeks contract as singing star. Finally, after two years of hard work came “Holiday in Mexico.”

The big build-up, the rave reviews, her new contract with Columbia records, and all the other super stuff rolls right off Janie. If she realizes it at all—she doesn’t seem impressed. The most startling change success has made in her evolves around the fact that she can’t go to a movie with her hair rolled up in curlers any more. She always dreads having to put her hair up in pin curls when she gets in late and sleepy from a show. And she used to put it up before she went out, then wear a bandanna over it. “It looks kind of bad that way. Particularly when I do it in rags. They stick out here and there under the scarf,” she says. Since her success she can’t risk the white rag coiffure at the neighborhood movie. She accepts it philosophically. Such is the price of fame.

If you drop in on her at their present rented bungalow Janie meets you at the door enthusiastically, with Ozzie in her arms, and Cindy bringing up the rear.

The phone is constantly ringing. And Janie beats her own track record to it every time. “Excuse me,” she says politely. “Maybe this is The One”—then all but trips over the rug rushing to answer it and find out. The One, of course, is the number one boy friend at that time, that week, that minute. As her mother points out, you can readily tell when it s The One. She adopts a very lady-like dignity, saying, “Oh . . . hellooo. How are youuu?”Then gradually closes the hall door.

Among the boys she dates now are Marshall Thompson, Johnny Sands, Hal Hackett and Roddy McDowall. She prefers dating boys in her own profession “because I think actors are the most interesting.

When it comes to boys . . . “I like politeness, but one who never falls all over himself being polite. Sincerity. Well sincere as far as you’ll know anyway. I cant stand a braggart. Oh, well he can brag a little,” she says as an honest after-thought. “And I like somebody who’s a little brighter than I am, but who makes me think I’m brighter than he is . . . only I’m not. I don’t mean Einstein and stuff. That’s too confusing,” she says.

She’s very excited about the new home they’ve bought out in North Hollywood. “It’s one of those rambling ones. It has a badminton court, a small swimming pool and a guest house with the front of it built like a ship. It’s a real Hollywood house,” she says.

The phone rings and she makes a wild dash for it. But the hall door stays open. It isn’t The One. “He’s such a boy!” she says reprovingly, as she comes back from talking with a swain just her age.

The phone rings. “Excuse me . . . this must be The One,” she says, bouncing off happily. “Oh, Hello,” you hear her say. “How are you?” The door slowly closes.

In Hollywood she builds her “own hamburgers” on the house at her dads little shop called “Paul’s,” on Sunset Boulevard. He’s constantly being asked why he runs a sandwich shop “when you have a famous daughter who’s a movie star.

The “famous daughter” is just as constantly around eating up the profits, feeding nickels into the shiny red juke box, and sampling her dad’s chili. “Pop makes the best there is,” she says admiringly.

In her new picture, “The Birds and the Bees,” Janie tries to run the life of her mother, Jeanette MacDonald, who realizes finally that she hasn’t told Janie certain things about the birds and the bees. It occurs to you that it might be only fair to tell the birds and bees about Janie too. Sort of prepare them.

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE JANUARY 1947