Have Luck, Will Travel—Leslie Caron

Leslie Caron, during her early dancing days in Paris, appeared one night as a clown in a ballet performance. As she pirouetted across the stage, her toe caught in a small break in the planking. The hole was just large enough to admit the padded front portion of Leslie’s ballet slipper. And there she was held imprisoned—a harlequin figurine poised like a statue.

Afterward, when there was time for reflection, Leslie thought, “I might have broken my ankle! How lucky I was.” At that moment, however, she only thought what a spectacle she was making of herself. If she didn’t get free the rest of the ballet company would leave the stage. She would be disgraced forever.

Galvanized by embarrassment, Mlle. Caron invented a series of gymnastic dance steps never again duplicated, and managed to pull her foot free.

She was limping a little as she finished a glissade arabesque into the wings. There she was met by one of her best friends in the corps de ballet, a superstitious type, as it turned out.

“It’s an omen,” the girl said. “It means you will have a lifetime of adventure—probably in traveling . . . a trip means a trip . . . but you will always emerge safely.”

“No doubt,” said Leslie dryly as she hobbled away in search of the stage manager to report the break in the planking.

Authentic omen or not, the fact is that the next major experience of Leslie’s life was fleeing south on a refugee train with her parents and her younger brother, Aimery. The Germans had entered Paris, and the loyal had fled or were fleeing by any means possible. For years afterward, Leslie had nightmares about the seething confusion of collecting and packing what family treasures could be carried away. Everything not portable had to be tearfully abandoned.

Next came the frantic trip to the railroad station to board an obsolete train already jammed with those who shared the Carons’ plight. There was no place to sit; there was scarcely a spot on which to stand. Once wedged in, there was no possibility of moving. Worse than the heat of hundreds of packed bodies, and the darkness (they moved in blackout), was the despondent, heartbroken silence of this multitude of hopeless humanity.

Unexpectedly enough, the trip ended in the Carons finding a place of safety. They had two rooms, riches indeed. True, one was no larger than a closet, but it served as a living room by day; a bedroom for Leslie and her brother by night. The “big room” served as quarters for Leslie’s parents, and it was in this space that a Christmas tree was set up to mark the Holy Season. There were no decorations available, of course, no lights, not even candles. Yet, out of wrapping paper, Leslie’s mother cut yards of “cat’s stairs” and festooned both the walls of her bedroom and the Christmas tree.

“It’s the Christmas tree I remember more sharply than any other we ever had,” Leslie remembers. “My mother was so brave that she gave us a brave tree, and a brave Christmas.”

The inconspicuous bravery of millions like Madame Caron, and the overt courage of other millions of her countrymen resulted in a happy day when the Carons were able to return to Paris, and Leslie was able to continue her career.

She was seen, signed to a picture contract, and invited to come to America to finish scenes for “An American in Paris” opposite Gene Kelly. So good luck did come at the end of a long voyage.

Although Leslie had seen much of the Americans in Paris, she was unable to accept their simple friendliness with more than watchful reserve. One of the first stories a French child learns is Aesop’s fable about M’sieu Renard, the fox, and M’sieu Corbeille, the crow. M’sieu Corbeille, had acquired a cube of sugar which he was holding in his beak when M’sieu Renard happened along. The fox coveting the sugar, made friends with M’sieu Corbeille, and observed, “Such a handsome bird must have a beautiful voice. Please sing for me.” M’sieu Corbeille opened his beak to sing and dropped the sugar, benefiting M’sieu Renard. To this day, Leslie is inclined to suspect the motives of M’sieu Renard in the kindly overtures of strangers.

In Hollywood, Leslie had a problem, again having to do with travel, which she took up with her agent. “Where would it be possible for me to buy a bicycle?”

The agent had his secretary draw up a list of near-by bicycle shops, and recommended that one of the light, English-racer types would be a practical purchase, “because you will be able to load it into the car and take it to the beach if you want to ride along the packed sand. And if it’s compact enough you can take it to Palm Springs where cycling is great.”

“I don’t believe I should buy a racer,” Leslie mused. “I think I shall need a heavier bicycle—one that will stand up under daily use and will last a long time.”

“Daily use?” said the agent, chuckling a little. “I’m afraid you don’t realize at what pace American motion pictures are made. You’ll be spending every day, excepting Sundays, at the studio for several months. You aren’t going to have much leisure.”

“Leisure! I do not expect leisure. I expect to report early to the studio in the morning, and to come home late at night. I have been warned. That is why I must buy a bicycle. When it rains, I am told, it is impossible to get a taxi, and in any case I do not care to pay taxi fare two times each day. Taxis, in Los Angeles, are very expensive. So—a bicycle.”

Miss Caron’s agent narrowly avoided swooning.

Patiently he explained the hazards of Los Angeles traffic, especially as applied to two-wheeled vehicles. He mentioned her natural fatigue at the end of a day of dancing, and drove her out to one of the hills lying athwart the highway between Leslie’s apartment and M-G-M’s acreage in Culver City.

“I shall have to learn to drive a car,” said Leslie. She added regretfully that it did, however, seem a needless waste of time. She knew how to manage a bicycle, even on hills. A car seemed a sad waste of money.

The agent lived to wonder whether Miss Caron’s idea of transportation might not have been the wise choice. True, she learned to drive a car quickly. She seemed to have a natural affinity for all means of transportation. True, she gave excellent hand signals. And she obeyed traffic laws—as long as they avoided the subject of speed.

Leslie is always a few moments late. For some reason, she believes firmly that having a nine o’clock appointment means that she must leave the house at nine o’clock. If the appointment is—as often happens in far-flung Los Angeles—ten miles away, she is almost certain to be about twenty minutes late, give or take a traffic jam along the route. During the trip, Leslie suddenly remembers that Americans are normally a punctual lot and that possibly she is about to keep someone waiting.

And so: “Pull over to the curb, please. May I see your driver’s license?”

“But what did I do? I am on my way to an appointment, so I cannot stop now. I am keeping someone waiting. I am sorry if I have annoyed you. You tell me what mistake I have made, and I will not make it again.”

“Miss, you were doing forty-five in a twenty-five mile zone.”

“I was! But I am so sorry. It was only because I realized quite suddenly that I was late. Please, may I go now so that I will not be later than before?”

“Appear before Thursday, the twenty-first, at the address listed on the summons, and take it easy, Miss.”

“I cannot appear on Thursday. I am working in a picture and I am in the shooting every day. Later, when the picture is finished, I will explain.”

The officer grinned a little. “Suit yourself, lady,” he said. “But if you let it go to a bench warrant, you’re going to have to face an annoyed judge.”

The sarcasm, gentle as it was, was lost on Leslie. “I will explain to the judge. I have known judges in France.”

She kept the summons in the back of her purse, along with other valuable papers. She stored her second summons in the same place, sighing a little in anticipation of the annoyance of that judge. She almost wept over her third ticket. It seemed that no matter which route she took, a twenty-five mile zone intruded to cause trouble.

Leslie was in the midst of the production of “Daddy Long Legs” at 20th Century-Fox when a deputy sheriff arrived with a bench warrant for the arrest of Miss Caron. Consternation was thicker than smog. Leslie explained that she had every intention of paying her fines, and what was the rush?

A phalanx of horrified studio officials explained some of the ramifications of California traffic laws to Leslie. Attorneys were assembled. Court appearances were arranged. “Altogether it is a lucky thing that I had good omens of travel in my favor, or I think I would have been sent to jail,” says speedy Miss Caron.

From that day to this, Leslie has never collected a traffic ticket.

Like most Europeans, Leslie has a strong feeling in favor of coming to grips with the earth by walking. She has walked, she believes, along almost every street in Paris, and has acquired much the same close acquaintanceship with London.

Armed with knowledge of two cities, Leslie set out to get acquainted with Beverly Hills. She soon discovered that it was impossible for her to walk a block on Beverly Drive without being recognized, but she could do quite well in Santa Monica or other beach cities.

In a way it is amazing that Leslie is recognized in picture-personality conscious Beverly Hills, because Leslie off-screen looks more like an unpretentious schoolgirl than an accomplished ballerina- actress. First of all, she is far prettier in person than even the color cameras reveal. Her skin is flawless in texture and color. The only make-up she wears is a pale lipstick. When the lipstick wears off, she isn’t in a hurry to replace it. She prefers flats for walking, and one of her favorite winter strolling outfits consists of a black sheath skirt, a fingertip-length beige cardigan buttoned from waist to throat, a simple string of pearls, and a voluminous black coat. She seldom wears a hat, but just when her friends have grown accustomed to the shaggy Caron top windblown in the breeze, Mile. Leslie is likely to show up looking like a manikin direct from the Champs Elysées.

Not long ago she arrived at a luncheon wearing a sheath dress, three-inch heels, and a brown velvet cloche from which bobbed a bright red Robin Hood feather.

“The new you?” she was asked.

“The revolutionary me,” was Leslie’s fierce answer. “I work so hard that when a picture like ‘Gaby’ is finished, I must do something mad. I must go wild . . . I must change my feeling.” On one occasion she had her hair shorn within two inches of her scalp. Luckily, she was not called for retakes.

Her most recent explosion took the form of a shopping spree during which she bought three hats. A brown cloche described above, a black cloche—“‘very French”—and a chic gray beret. Then, just to prove that she could, she made a hat for herself, “for purposes of the beach and sitting in a chair in the sun.”

The fabric she chose was a recent addition of Paris Soir, which she reads daily. The style she chose was early Chinese rice-planter, and the joints were fastened by bobby pins. It turned out to be an excellent sunshade: crisp, protective, and theatrical because, on the upper front elevation there appeared a large picture of Kirk Douglas.

One of the most appealing properties of this hat, in Leslie’s opinion, was its individuality. She has a horror of the stereotype. She thinks that the worst thing to befall a private citizen is similarity to the point where he can be classified at a glance by a spectator as a member of some specific group. You know: briefcase for an attorney, hatbox for a model.

A friend once told Leslie, “I swear, if you were a doctor, I believe you’d carry your pillbox in a birdcage for fear of looking like every other doctor.”

It is true that when every other young actress was appearing on the lot wearing a tailored silk shirt and a double-circle skirt over fourteen petticoats, Leslie was wearing a near-Chinese sheath. When all the curlyheads on the lots were wearing their hair in the wayward curls of the Italian haircut, and all the non-curlyheads were having tight permanents every six weeks so they could be gamine too, Mlle. Caron wore a coiffure strongly reminiscent of The Strawman in “The Wizard of Oz.”

Since this is a story, primarily, of the Caron travels, it should be noted that Leslie’s accomplishments in individuality extend far beyond appearance or even her unique talent. On her one and only sea voyage from France to the United States, aboard the French Line’s resplendent Liberté, Leslie was “adopted” by the crew and was taken on a tour of the ship. At the end of such a trip, it is customary for the guest to be returned to her cabin with ceremony and there left.

Not so in Leslie’s case. She was invited to have dinner in the Officers’ Mess, accepted, and loved every moment of it. She is one of the few women ever to have been so honored. “It makes me a little different from everyone, to have been accorded such an invitation,” she says proudly.

Obviously, this story has a moral. The next time you trip, falling flat on your face or elsewhere, be brave! Just remember what such an omen has done for Leslie Caron and be ready to welcome similar benefits.

One of the first of such benefits should be a trip to see “Gaby.”

THE END

—BY FREDDA DUDLEY BALLING

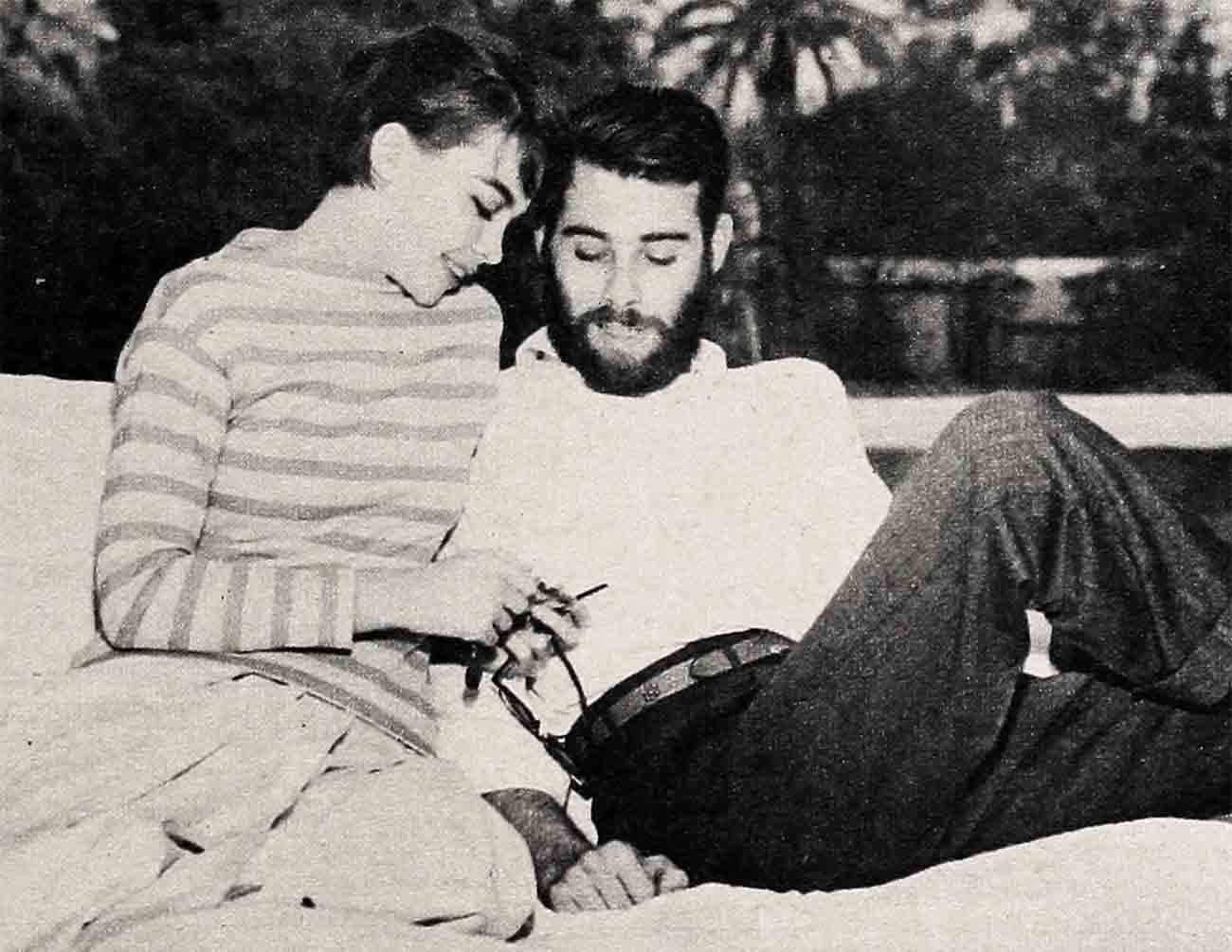

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE JUNE 1956