A Xmas She’ll Never Forget—Ingrid Bergman

Four years ago, Ingrid Bergman spent Christmas in Alaska, and discovered all over again the meaning of the day.

It was her husband’s idea that she should go. She’d just finished For Whom the Bell Tolls. The thought of a USO tour had been long in her mind. But she was no Crosby or Hope or Danny Kaye. What could she. do to entertain?

Day after day at the hospital, Dr. Lindstrom’s contacts were among the sick. The soldier’s problem, he felt, was not too different from the patient’s.

“He is lonely, he is far from home. It’s enough that someone should walk in from outside and say how are you. Especially now with the holidays coming.”

So she talked to David Selznick, to whom she was then under contract. Would he find out whether the USO could send her some place where there hadn’t been much entertainment?

Nothing simpler, chortled the USO, hauling out its maps. They’d be enchanted to send Miss Bergman to Alaska, where the boys had seen precious little entertainment. Miss Bergman, they hoped, had nothing against snow.

Snow was all she needed to hear. Through winter after winter among the palms and sunshine of California, Ingrid had ached for Christmas in the snow. Alaska would be perfect. Only, before definitely committing herself, there was another member of the family to consult.

Pia was five then, a little young for understanding. Yet Ingrid explained so that Pia understood. About the soldiers who’d been in that faraway country for two and three years, to make the world a better place for Pia and children like Pia to grow up in. About how Ingrid wanted to go and thank them, but it would mean being away from Pia at Christmas time. Would Pia forgive her?

Listening, the little girl’s eyes clouded with pity. “Oh yes, I want you to make them laugh.”

“The only trouble,” said her mother, “is I don’t know what to do for these soldiers.”

“Why don’t you tell them stories like you tell me?”

That gave her her first idea. Hunting through story material that would fit Christmas, she found O. Henry’s “Gift of the Magi,” and made a simple dramatization of it. Then she could sing them some Swedish folksongs.

For that, her friend, Ruth Roberts, dug a Swedish peasant dress out of her attic. It was cleaned and made over to fit. For the rest, Ingrid packed simple things; not so much as a cocktail dress. Just plain clothes that the boys would feel at home with.

To round out the program, she wanted something serious, and decided on a couple of Maria’s scenes from the Hemingway picture.

People warned her against this. “It’s not even released yet. Besides, the boys don’t go for that heavy stuff.”

Maybe not, thought Ingrid, but it wouldn’t hurt to try. If she found that Maria bored the boys, she could always drop her.

They were a group of five who left by train for Seattle. Ingrid, Neil Hamilton, actor and master of ceremonies, Joan Barton, the pert little radio singer, Marvelle André, hula dancer and Nancy Barnes, whose accordion supplied their only music. Her husband, captured early in the fighting, was in a German prison camp. On receiving the news, Nancy had picked up the accordion she’d never played professionally, and applied to the USO. Through all the weary years of waiting and wondering whether her own soldier would come home, she went wherever they sent her to bring what cheer she could to other soldiers.

At Seattle, the five got their Arctic issue—parkas and fur boots—then off to the north by Pan American Clipper. For Ingrid, Christmas started the evening they landed at Anchorage—when she stepped from the plane and lifted her face to the snowflakes, falling softly over layers already fallen. When, at Clemendorf Field and Fort Richardson (it was a huge base, combining the two) she saw their welcome, glowing in the men’s faces. When they were taken to meet General Buckner—the same gallant Simon Bolivar Buckner who eighteen months later was killed on Okinawa—and he spoke his simple words of greeting and appreciation.

The big doings were scheduled for Christmas Eve. In the afternoon, they’d gone from ward to ward of the hospital. Now they stood in the wings on the stage of the auditorium. The boys had gone to work on the auditorium walls, painting them with reindeer and sleighs and fat Santa Clauses and—in one quiet space—the Manger and Child and the Three Wise men on their donkeys. Maybe it wasn’t art, but it was certainly Christmas.

Neil went out first, then he introduced Nancy. Watching her, Ingrid felt that her manner set the keynote for them all. “None of that here-I-come-and-give-you—” she described it later. “Nancy just sat there and played, as if she were playing for her husband at home.”

Next came Joan, dark-haired and laughing, doing her comedy songs. She put them right in the mood for Marvelle’s hulas. Marvelle soloed first, then coaxed a couple of the fellows to dance with her. Neil followed this with a few magic tricks, assisted by Joan, after which the boys clamored for another song.

something to remember her by . . .

“What would you like?” she asked them.

And as if with one voice they called: “Oh, give me something to remember you by.”

An old tune, and not at all a gay one, Ingrid noted, as the plaintive melody rose, and the house fell still. Well, then, maybe she hadn’t been wrong about Maria.

Now came the moment she dreaded. Stage fright? No. Even worse than that. Now she must listen while Neil introduced her.

Famous actress from Hollywood, great honor to have her with us and so forth and so on—

“Please don’t, Neil,” she’d begged, at rehearsal. “It will make them laugh. They’ve been up there so long, they’ve never even seen me.”

“I don’t care,” said Neil. “Sooner or later they’ll see you.”

So she stood there blushing, waiting for the cue, imagining the whispers:

“Who is she, did you ever see her?”

Ingrid won’t tell you of the roar that went up to greet her, but Joan and Nancy will. Some of the boys must have seen Casablanca, or else they just liked the way she looked. Joan and Nancy will also tell you about the moment when liking turned to love.

To break the ice, Ingrid, too, did a couple of magic tricks with Neil. Then he left the stage to her and Nancy.

“I brought this Swedish dress all the way from home,” she began, “for an excuse to sing you some Swedish folksongs.”

If you saw Bells of St. Marys, you know how charmingly she sang them.

One song in particular—“A janta a ja”—went over big. They thought the ja-sounds were very funny.

“It would be nice,” said Ingrid afterward, “to sing it together, and it’s really not difficult. You listen and say the words after me. A janta a ja—”

“A janta a ja,” they roared obediently.

“Alto polanda vegen a ja—”

“Alta polanda vegen a ja—”

“I think we can still make it a little easier. Are there any Jansens and Svensens in the audience?” A lot of blond boys got to their feet, grinning. “That’s fine. We Svensens will lead.”

It brought down the house. Flushed and laughing, she waited for the hubbub to die. . .

“Now, to finish this part of the program, I would like to dance a little polka that I learned as a child—”

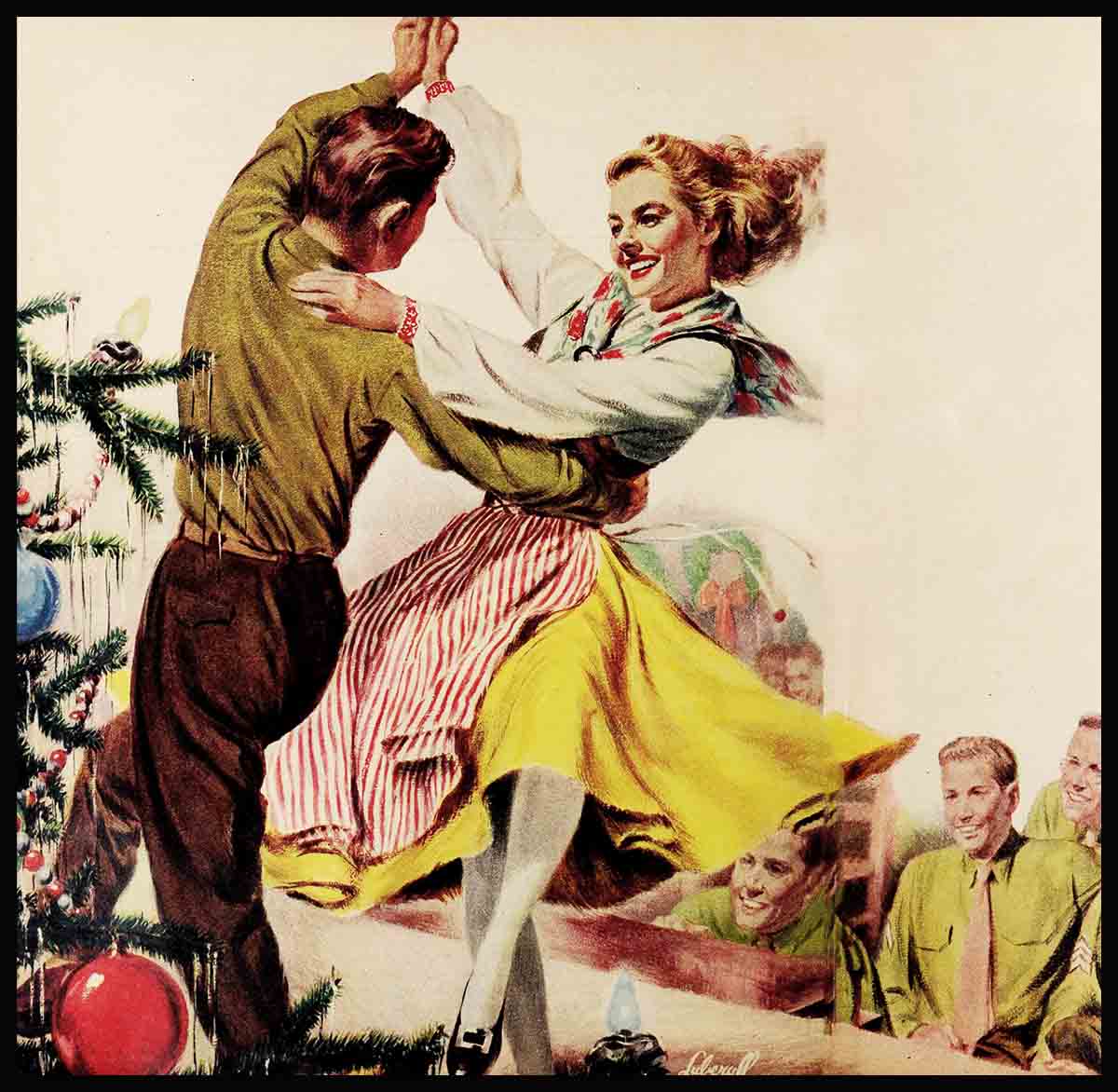

What followed was completely spontaneous and unrehearsed. A GI jumped up and rattled off some Swedish at her. She smiled and nodded, rattling off some Swedish back. An invitation to the dance, as the others soon found out, and the lady had accepted. Down the aisle ran the soldier, vaulted to the stage and took his place opposite her. Nancy started the accordion.

“And there,” says Ingrid, still laughing at the memory, “we went off jumping.”

From that point on, they’d have sat enthralled while she did the multiplication table.

She did Maria, instead. Neither then, nor at any of the spots they played later, did the boys seem to Maria too serious. On the contrary. Many who knew the book realized that what had happened years earlier among the mountains of Spain had a very direct connection with their presence here. Ingrid told them about the movie and how it was made. She sketched the background leading up to each of her scenes. And it was their response that sent her home to tell all who’d listen: “Make an overseas tour, not, so much for the boys as for yourself. It’s an audience you’ll never find among people who come in and pay to see you. It’s the kind of audience actors dream about.”

Gift of the Magi, with Neil playing the man, wound up the show. But that was only the shank of the evening. Out of the auditorium, under the starlit night, they streamed across the snow to the big canteen, where the Red Cross had prepared a Christmas party. Mountains of ham and turkey, acres of pie, rivers of coffee.

Nancy and Ingrid, Joan and Marvelle helped serve the customers—some too bashful for more than a smile as they took their food, others so eager to talk that it took a dig in the ribs from their buddies to get them going.

There were gifts, too, packed by the Red Cross, which the girls helped distribute. Then the jukebox was started for dancing, and of course the boys stood in line to cut in on the visitors who never got more than a few whirls with each. But even while they danced and laughed, their eyes remained sad. And why not? What did the immediate future hold for them but more grinding monotony and loneliness at best? And at worst—

She was glad when the dancing stopped, and they sat down on the floor to sing Christmas carols. Now, at least, they wouldn’t have to pretend. You can sing without forcing a smile on your face. You could even perhaps get some kind of release from those songs dedicated to the birth of the Man of Sorrows.

where do we go from here? . . .

As if to put the mood into words, a boy stood up. He couldn’t have been more than 19, and he spoke very simply.

“I’m not for speeches any more than the rest of you, so what I’ve got on my chest I’ll get off it quick. This is my first Christmas away from home. The same goes for a lot of you guys, and on the other hand, some of you haven’t seen your folks in two and three Christmases. We don’t know how long we’ll be hanging around here, or whether we won’t be in some worse place a year from now. But so far we’re safe and healthy and alive, and that’s a lot to be grateful for these days. So I think we ought to sing The Lord’s Prayer to thank Him.”

For Ingrid, who’s heard it before and since but never so movingly, The Lord’s Prayer will always mean a great shadowed room, flickering with Christmas lights, and the voices of hundreds of men.

When it was over, nobody stirred for a moment. Then a door was opened on the frosty air and the spell was broken and they dashed for hats and coats. It was 11:30. At the Post church, they were preparing to celebrate midnight mass.

By the time services came to an end, the moon was out, and the boys obviously had something more up their sleeves.

“Of course,” they said, polite but wistful, “we don’t want to keep you girls up if you’re tired but—”

But the baseball park had been flooded for skating, and it looked unbelievably lovely in the moonlight, and of course the girls wouldn’t have missed it for anything, so they skated their legs off until 3 in the morning, then went home and gathered in the kitchen for fruitcake and wine, sent over with the compliments of General Buckner, while they opened Christmas packages from their families.

They didn’t expect nor want nor get much sleep. But they couldn’t figure out the sound of sleighbells next morning which seemed to come from right inside the house. Marvelle rolled out of bed and trailed the jingle to its source.

“It’s the phone,’ she squealed. “The telephone rings like sleighbells.”

And it kept on ringing, bringing so many invitations to breakfast and lunch that the girls divided forces and ate at different mess halls. Again they went to the hospital, and sang the same songs over and over. But mostly that day they sat and talked to the boys, though Ingrid remembers with humor and compassion the boy who didn’t talk.

All he said to her was yes and no, looking hunted, and finally he shoved his chair back in desperation.

“You’ll have to excuse me. It’s two and a half years since I talked to a girl. I don’t know how any more.” And he turned and fled.

But he was the exception. For the most part, in ward or mess-hall, what struck Ingrid was their hunger for talk.

It wasn’t your being in the movies that made it important. They were just as happy, says Ingrid, to talk to Nancy, who wasn’t a professional at all. They asked questions about Hollywood, but many more about home. What was it like in the States now? What were people doing? When did they think the war would be over? They showed you snapshots. An MP, the father of four children, drew Ingrid into a long and earnest discussion on the raising of youngsters. One boy said: “Just to see someone from home—it’s a little as though you’d been home yourself.”

And through ali their talk ran one ever-recurring theme—that Neil and the girls should have come for the holidays, at a time when everybody most wanted to be with their folks! That Ingrid should have left her little girl—

To be thanked was more than she could bear. “We come for a few weeks. You others are doing so much more—”

“It’s our job.”

“It’s our job, too. And,” she added, “a great privilege, besides.”

the real meaning . . .

Next day, as the plane rose over Elmendorf Field on its way to their next stop, Ingrid felt it was she who owed a debt of gratitude. Almost every year since coming to America, she’d been working at Christmastime. Working till the last minute. Scrambling to buy gifts. Resting all Christmas day because she was too tired for anything else. Somewhere in the shuffle you lost the meaning of the season. Here, it had been restored. Christmas was nothing unless you gave of yourself to meet the need of others, whatever that need might be—the warmth of a coat or the warmth of a friendly hand. Actually, you were giving to yourself in values that couldn’t be measured nor bought in a shop.

“It’s their gift to me,” she thought. “A Christmas I’ll never forget.”

Six weeks later they were home, the whole thing a howling success but for one disappointment.

Pia had expected her mother to bring back a bear.

That was four years ago.

This Christmas, Neil Hamilton’s in New York, after a road tour with State of the Union.

Marvelle, married to the police chief of Burbank, has retired from professional life.

Joan’s still in radio and has just finished Mary Lou for Columbia.

Nancy’s husband did come back. They have a baby.

Since first starting in movies, Ingrid’s dream of dreams has been to do Joan of Are for the screen. This Christmas her dream is coming true.

Most of the boys at Anchorage—those who stayed safe and healthy and alive—are at home. The war is over, but the peace isn’t won—largely because all over the world except here people are hungry. That’s why Ingrid holds tight to what she re-learned four years ago. That Christmas is nothing unless you give of yourself to meet the needs of others.

THE END

—BY ABIGAIL PUTNAM

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE JANUARY 1948