Bronx Blockbuster—Perry Lopez

Perry Lopez comes to you through the courtesy of sheer accident. In the first place it is the result of sheer good luck that Perry is among us at all; in the second place, the acting career that is astonishing Perry himself and delighting his fans, has come to him as haphazardly as three bells showing up on a slot machine.

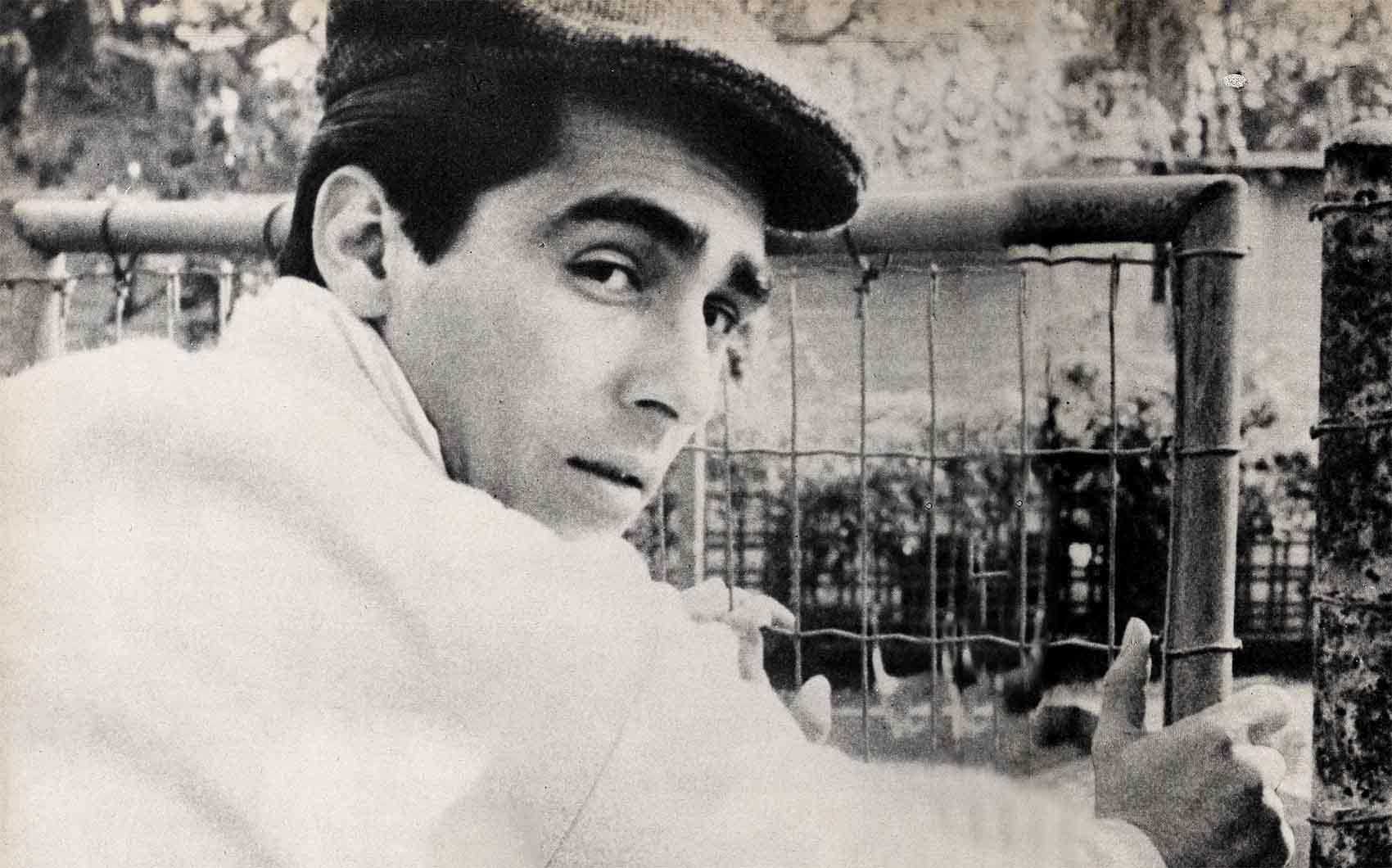

So far, Perry has been in seven motion pictures: as Spanish Joe in “Battle Cry”; in minor roles in “Mr. Roberts,” “Drumbeat,” “The McConnell Story,” “Hell on Frisco Bay,” and “The Lone Ranger”; and in the lead in “The Steel Jungle.”

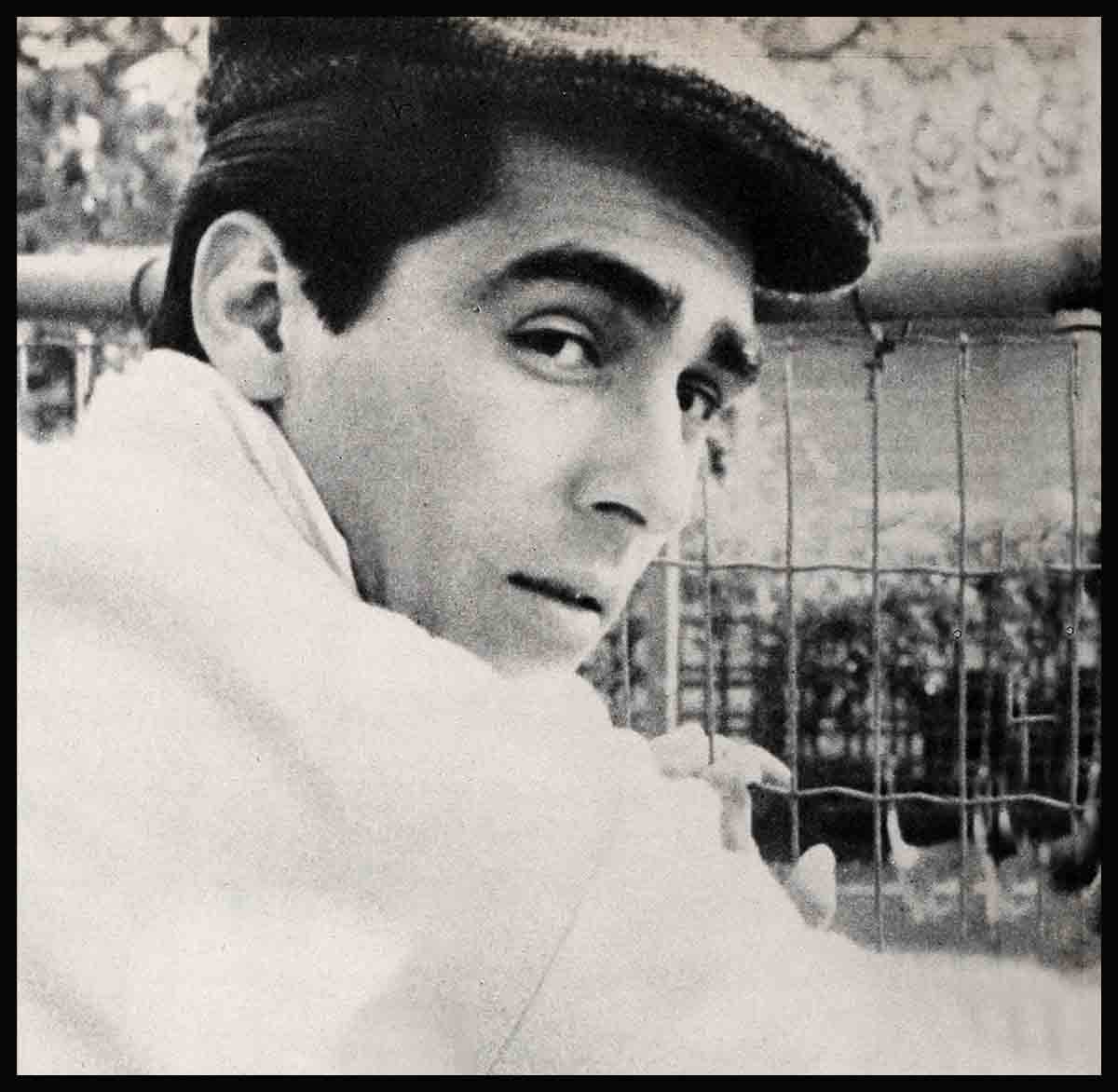

Perry is five-feet eleven, weighs 170 pounds, has magnificent, sweet brown eyes, black hair, and the sort of masculine good looks that a photographer could create from a composite of portraits of Desi Arnaz, Anthony Quinn, and Cesar Romero. Perry’s two great extravagances are buying boots (paratrooper boots at Army surplus stores, hiking boots, riding boots, ski boots), and hunting jackets.

He reads during most of his spare time (particularly admires the works of André Gide and Thomas Wolfe), saves his mother’s letters (she lives in San Francisco) and reads them over and over again to savor their quiet wisdom (she still calls him “Honey-bunch,” a practice against which all others on earth are hereby duly warned), plays a medium game of tennis, and an exceptional game of chess (trembling and incredulous, he once defeated the great Oscar Hammerstein in a chess game backstage during rehearsals for “South Pacific”).

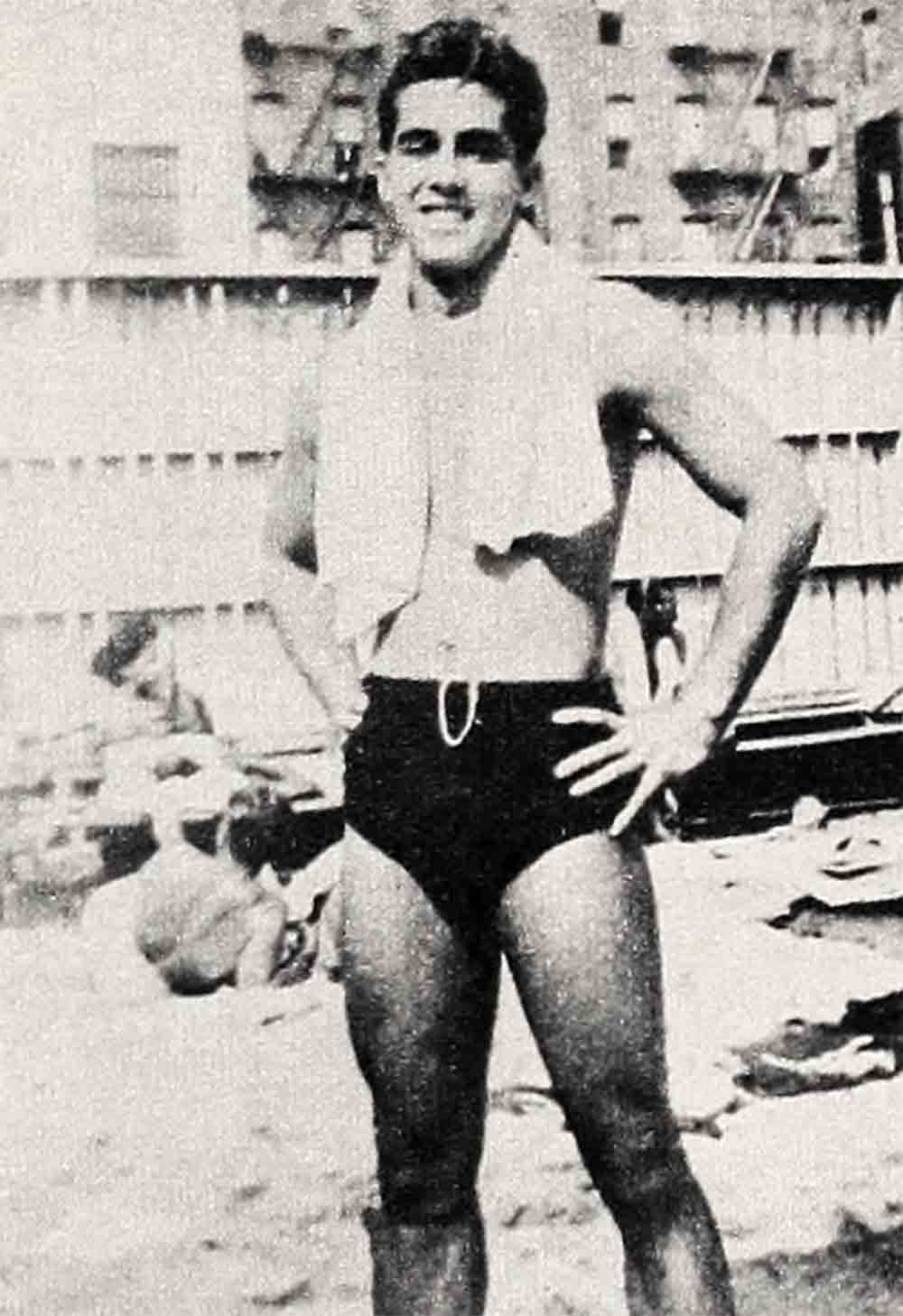

This battle of wits represented Perry’s second ghastly attack of stage fright. The first occurred during his formative years when he was one of the most accomplished swimmers. (He also dabbled in hockey, basketball, football, baseball and boxing.) On one occasion he won a 150 meter race, but he insisted that his buddy march up to the judges’ stand to accept the medal and have his picture taken.

But, to begin at the beginning: Mr. and Mrs. Lopez had no particular reason to regard the moment as rainbow-wrapped when their third son was born. The year was 1931, a sub-basement era of the Depression, and the day was a sweltering July’ 22, as noted on limp calendars on the walls of New York’s Italian district.

Perry’s father was a postman and a man who lived in accordance with the concepts of old Spanish culture and therefore believed in the power of maxims customarily taught to the young. One of his favorites was “Early to bed and early to rise, makes a man healthy, wealthy, and wise.”

This couplet impressed the Lopez brothers very little. Perry, especially, hated to come in from the street until he was reasonably certain nothing much was going to happen during the rest of the night. He soon discovered that if he came home before his father had gone to bed, but after the dinner hour, he was due for the snap of a strap. However, if Perry waited until after ten, at which hour Papa Lopez settled into the solid sleep of the pure in heart, punishment was avoided.

“Naturally, my hours grew later and later,” Perry remembers.

And his mischievousness, quite as naturally, increased. Perry didn’t belong to a gang, but he had a group of associates with fertile imaginations. Sometimes, their activities were confined to seeing movies at the Boys’ Club, or at the Catholic Youth Center. Other times, mischief sent the boys out to perfect their pitching control—by rehearsing with rocks near a many-windowed building.

On one such occasion, the tinkle of broken glass was quickly followed by the shriek of police whistles, and the boys found themselves facing a stern warning. Older hands at the disorderly conduct racket had cautioned newcomers like Perry that the thing to do, when caught, was to sob with great remorse. “Bust de cops hearts, see?” he was advised.

Although he was scared within an inch of drowning himself, Perry couldn’t cry, but he was so ashamed, he wished he could dissolve in his own tears.

After that, Perry readily agreed to report to the Police Athletic League where officers gave (and still give) many of their free hours to the job of using up excess junior energy in acceptable pursuits such as boxing.

To his own pleased surprise, Perry discovered that his footwork was agile, his reactions swift, and his right fist a leather-encased load of dynamite. He began to knock out fellow PAL members and took an interest in the life story of Henry Armstrong. It was easy to think of himself as “Hammering Hank Lopez.”

One day, Perry said to the police sergeant instructing him, “Get me some fights. I’m ready to move out of this division.” He was twelve then.

Over on Manhattan’s Lexington Avenue around 104th Street, there was another young pugilist who had let loose with his gloves on a list of hapless lads, and who believed himself ready to donate bigger and blacker eyes to anyone begging for trouble. He and Perry were matched.

At this point, there occurred one of the fortunate incidents mentioned earlier. On the night of the fight, Perry heeded the bell by charging his opponent like a bull after a red cape. The other boy stood his ground like a farmer armed with a pitchfork.

In brief, Perry’s opponent hit him with everything except the floor, and Perry hit the floor. Yet, Hammering Hank Lopez lived. That was the vital fact to consider, Perry told himself, when at last he began to detect the sound of human voices amid the clanging of bells and the twittering of birds.

This is probably as sensible a place as any to give you the news that Perry was actually christened Julius Caesar Lopez. Wisely, his mother nick-named him Perry, and it might be well for you to forget the label on Perry’s birth certificate because although he may have lost all interest in boxing as a career, Perry still doesn’t care much to be called—er, you-know- what.

Perry was educated in New York City. at PS 83, PS 172, Benjamin Franklin Junior High School, PS 43, George Washington High School, and—during one semester of night school—at New York University, where he intended to earn a law degree. Destiny, however, had no intention of turning him into a barrister.

One Friday morning, Perry was standing backstage at the Majestic Theatre, waiting to see a friend, when a stranger strode up to him and asked, “Are you an actor?”

Remembers Perry, “I asked him who he thought he was kidding.”

The gentleman insisted that he wasn’t kidding, and ventured another question: “Do you speak French?”

“Naw, I don’t speak French,” said Perry.

“Will you,” said the man, “repeat after me: ‘Allez-vous-en, vite, dans la maison.’ ”

Perry figured he couldn’t lose much, so he repeated the French sentence, copying the gentleman’s inflection perfectly.

“You’re sure you aren’t an actor?” the man asked again.

“Aw, for—what’s this all about anyhow? Who you kidding?”

The gentleman explained that if Perry was interested, he might report at the gentleman’s office for further interviewing, and proffered a card. The gentleman was Joshua Logan. A Chicago company of “South Pacific” was in the assembly stage and Perry was tabbed for one of the Marine roles.

Nowadays, when Perry thinks back to that crucial afternoon, he develops a set of shakes that would shame an earthquake. By such a slim margin, he might have failed to be at that particular theatre that particular morning during those particular thirty minutes. By such a slim margin did he escape antagonizing the celebrated Josh Logan to the point of giving up his talent-scouting of Perry Lopez in favor of some other likely Latin lad.

Night after night, Perry watched “South Pacific” unfold. He studied technique without knowing its name; he studied voice control, pantomine, and timing without realizing how much he was absorbing. He became a friend of Ray Walston, who was doing the Luther Billis part, and from Ray he assimilated a world of dramatic know-how. Next, Perry enrolled as a student of David Itkin, who had taught the elements of dramatic art at St. Paul University and at Chicago’s respected Goodman Theatre.

At about this time, “Cyrano de Bergerac” was playing in Chicago, so Perry undertook a weekly course of “study” under the tutelage of Jose Ferrer, the star of the picture. Every Sunday when the “South Pacific’ company rested, Perry paid his tuition at the box office and spent most of the day observing the manner in which Mr. Ferrer fetched up a dramatic storm in “Cyrano.”

After a year’s run in Chicago, the “South Pacific” company took to the road, bringing three crucial experiences to Perry. The first occurred when he was in Denver and picked up a copy of Battle Cry and met Spanish Joe. “When they turn this book into a picture,” he vowed, “I’m going to be Spanish Joe.”

The second occurred while the company was in Los Angeles. Perry scrutinized Southern California and liked what he was able to see through the smog. After all, sound stages were air-conditioned, and that, he had decided, was where he wanted to be.

The third crucial experience happened on the return loop of the tour. The train on which the “South Pacific” company was traveling crashed into the rear of a freight train which had failed to clear a switch as quickly as scheduled. Perry was catapulted against the side of his berth, suffering a concussion and a slight skull fracture. Still, he was lucky. If he had been lying down rather than sitting up, his neck might well have been broken.

Possibly, Perry regarded this as an omen, indicating that the time had come for him to abandon the roving life of a road show. The more he thought about it, the more he was convinced that he had taken all the giant steps possible in the “South Pacific” situation, and that from then on, he would only be marking time without rolling up any dramatic mileage. So he left the cast in Detroit and hurried to New York, his family, and the pulsating activity of summer stock.

His first job (for $35.00 per week) was in a “Stalag 17” production in which he had a few lines. His next job (for $40.00 per week) was in “Mr. Roberts” in which he had a few more lines.

As soon as it was possible, Perry decided to move to California. Once there, and having heard that Warner Brothers was casting “Battle Cry,” he called on Solly Biano, who interviewed Perry, then took him to meet director Raoul Walsh, who was impressed. Walsh tested Perry and arranged for him to be placed under contract. Right from the start, says Perry, “I tried to persuade them I was a Tony Quinn type, since they wanted Tony for the picture. I persuaded and persuaded until I wore them out and got the part.”

It took only one week of showing “Battle Cry” across the nation to prove that the youngsters were set to dig Perry Lopez the most. The fan mail began to pour in.

One of Perry’s most ardent fans, his mother, is now about to start a one-woman crusade against permitting actors to die in movies. Mrs. Lopez has seen “Hell on Frisco Bay” and “The Lone Ranger” many times, and each time she is crushed by the untimely cinema end of her son. In “Battle Cry,” originally, Spanish Joe was set to perish, too, as he did in the book. But in the final screen version, he was spared. Mrs. Lopez reasons that if so sensible a script change could be made in one picture, it should be made in all.

Naturally, she has been spared the knowledge that there are times when, entirely aside from script demands, the life of an actor is a precarious one, indeed. And Perry is no exception. While “Drumbeat” was being filmed, Perry had a busy bit of business requiring him to ride a horse, bareback, down a rock-studded hill. Perry was asked to fire a rifle over the head of his horse. Apparently, when he did so, the blank wadding shot from the gun passed too close to his mount’s ear. Panic-stricken, the horse reared and tried to climb the sky. Perry executed a brilliant one-and-a-half somersault into the Arizona desert. There was no explanation, other than the intervention of fate, how Perry managed to emerge in one piece from cactus, sand, volcanic rock, and an occasional rattlesnake refuge. For several weeks after, his torso was black and blue. However, no lasting damage was done.

“By that time,’ observes Perry, “you might say that I had bumped my head so many times I had developed a sort of built-in crash helmet—I hope.”

Recently, Perry was signed for the Prince Ahmed role in “Omar Khayyam.” This part will doubtless include riding horses, climbing balconies, engaging in duels, enjoying a snack beneath a flowering bough—the latter of which is likely to prove the favorite of fans.

Currently, Perry has two secret ambitions: someday, he hopes to recreate on film the matchless daring, gallantry, deviltry, and larceny of Joaquin Murriata, California’s answer to Robin Hood; and he hopes someday to explain Pancho Villa by portraying the Mexican bandit as a young man.

You have a question?

Oh … Perry’s love life. He is unmarried, and his idea of a good date is an evening spent at a movie or the theatre, followed by a spirited discussion of the script and the manner in which the acting dramatized the story. Perry is a good ballroom dancer (he is also studying athletic ballet in the Gene Kelly manner and hopes to perfect a technique that will make it possible for him to do musical roles), he likes tennis, listening to recordings, sitting in front of blazing fires, and talking.

The future looks bright to Perry, bright and clear and the clearest area is the romance department. Perry doesn’t intend to marry until he has acquired such prestige that his name on a theatre marquee will have the customers standing in long lines.

However, he has one modification about this: “Naturally, it would be nice to make the grade in a big way. But I want something more than obvious success in this world. I don’t know quite how to explain it without sounding corny, so I’ll go ahead and sound corny. I want to be a useful human being, serving a good purpose in the world. Okay, now grin.”

It is likely that no one is going to grin, except in a nice way, while applauding this intriguing young man heartily.

THE END

—BY ROBERT EMMETT

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE JUNE 1956