Grace Kelly: “If Only I Could Tell Him What I’m Really Afraid Of—”

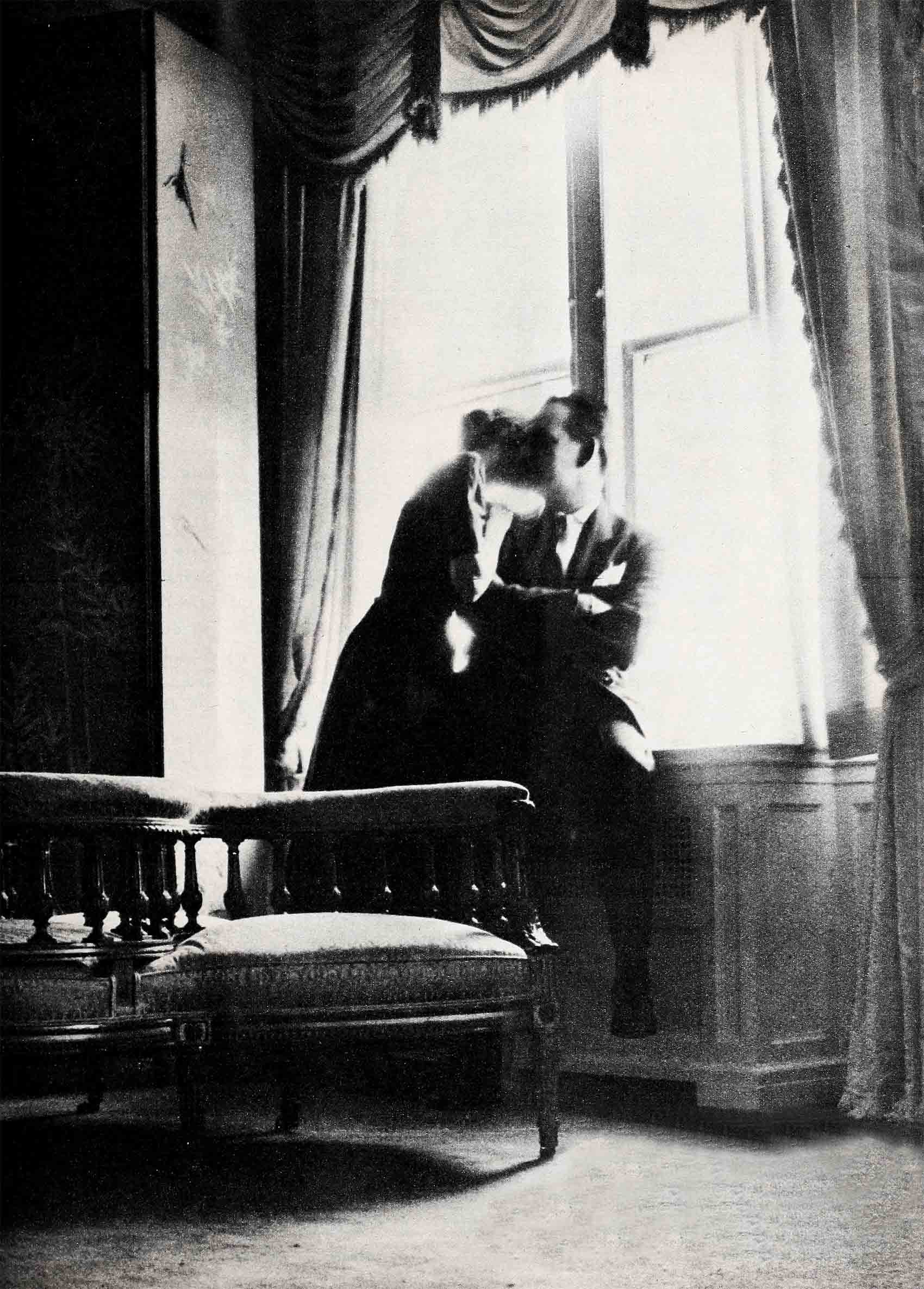

Leaning wearily against the draperies, Princess Grace paused as though to gather strength before speaking, and then, finally, turned to her husband. “It’s been a difficult day, hasn’t it?”

Prince Rainier sank back on the window-seat, let his arms drop to his sides and nodded.

Though the late afternoon sun was no longer in her eyes, the Princess kept a hand over them—so that he can’t see my face, she thought—as she looked up at him with a weak smile. Finally, no longer capable of pretense, she let her head fall loosely on his shoulder, closed her eyes and relaxed for the first time since early that morning, when the pains had begun again.

If only I could tell him, she thought, if only I could explain what I’m really afraid of. . . . Not now, she decided, not when he has so many worries already. Besides, I’m sure it’s not anything really serious. I’m just being oversensitive.

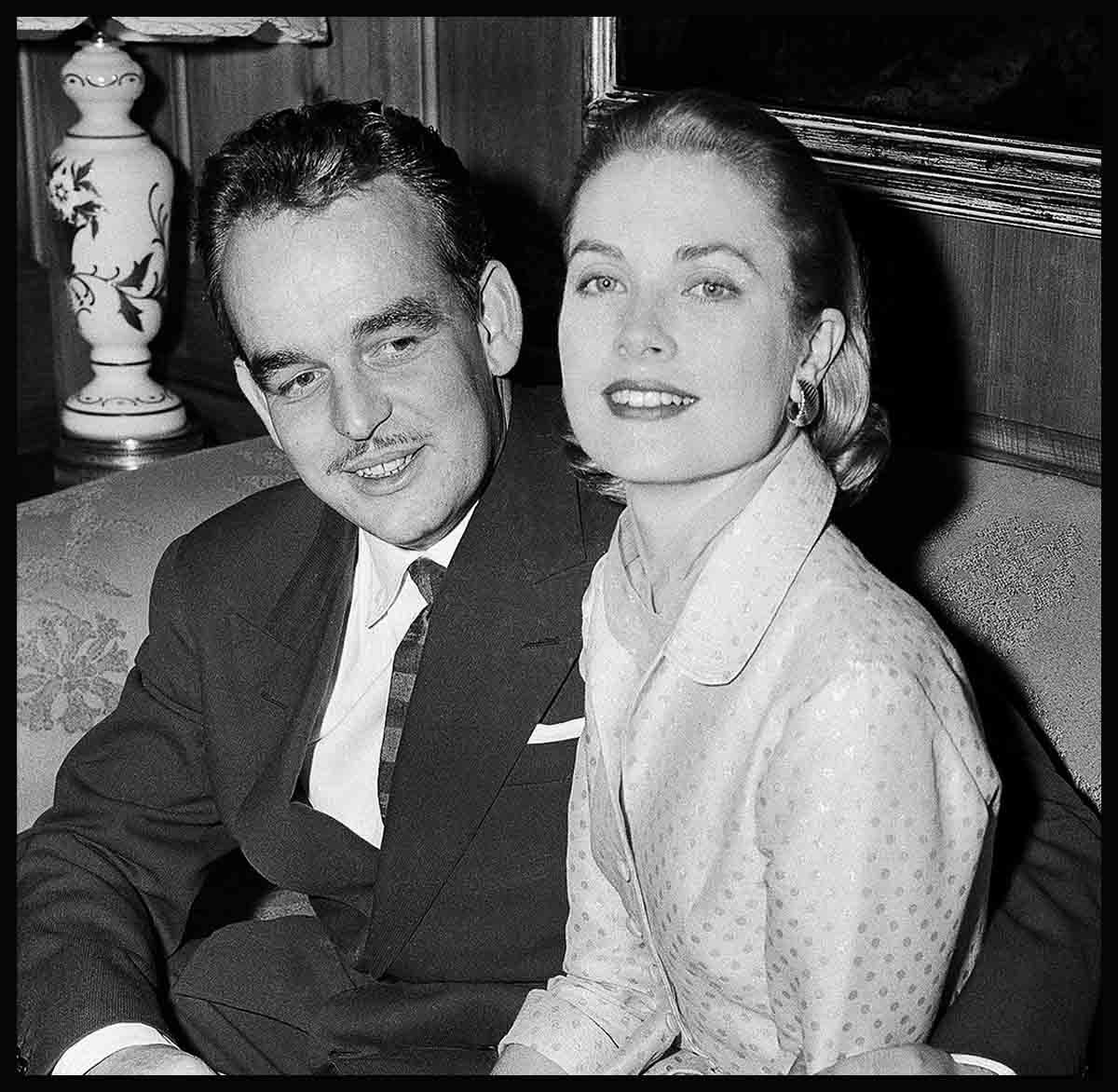

She opened her eyes, leaning her head sideways a little so she could study her husband’s profile. She never tired of looking at him, though she knew every inch of his face so well: the wavy black hair that somehow stayed in place even when he drove through the countryside in one of his sports cars; the thin mustache outlining his fine mouth; the patrician nose; the soft, deep eyes that could reflect concern one moment and gaiety the next.

But now, as she watched, she saw neither of these things. He seemed not to feel she was looking at him, and she noted an expression there she’d never seen before: it was a tiredness, but it was not of the body. It was a tiredness of the spirit. Here, in this unguarded moment, was clearly the face of a leader who, in trying to do his best for his people, was finding his actions misunderstood, his decisions misinterpreted, by almost everyone.

I cannot add to his worries now, she told herself. He has too much on his mind already. But when she felt his hand tighten around hers, she was grateful for his nearness. After the events of this afternoon, she, too, needed to be reassured, comforted . . .

It was supposed to be just another routine visit to the doctor. She’d gone to see him about a cold—the cold that had plagued her since childhood, that always settled in her nose and gave her voice its peculiar nasal quality. But while he was examining her, she remembered the little pain she’d had in her side recently, and she told him about it.

“Hmm,” he’d said, “we’d better have a look.”

Then, afterwards, when she was dressed again, she sat across the big mahogany desk from the doctor, waiting for him to finish making notations on her card. He looks so worried, she thought, squinting against the sunlight to see him more ay. I wonder why he looks so worried.

He glanced up then, caught her eye and looked away, as if he didn’t quite know what to say.

“Doctor,” she said, “what is it?” She half rose from her chair.

“Oh, it’s nothing,” he said. “Nothing serious, anyway.” But still he wouldn’t meet her eyes. “It’ll be a few days before we’ll know for sure just what it is,” he added.

“Now don’t worry,” he said, and came around the side of his desk to take her hand. His voice seemed too hearty.

Twisting her white gloves into a ball, she wanted to shout, “Tell me the truth! Tell me!”

Suddenly she shivered.

“Take these pills,” the doctor said. “I think you’ve got a little chill with this cold.” He pressed a box of tablets into her hand.

“No, I—” She wanted to ask again: What is it? But her throat was too dry. She couldn’t speak.

As if she had no will of her own any more, she allowed him to help her on with her wrap, to open the door for her, to say goodbye. . . .

That night she slept fitfully and in the morning she was still tired, but she would not miss breakfasting with her husband or going in to see little Princess Caroline and Prince Albert. This was the magic hour of her day, the time when all problems seemed to fade away, and she was just a mother alone with her children.

At three o’clock, feeling a little better, she went to a hospital to inspect the new operating room. As she walked toward the swinging doors that led into the new, room, white and antiseptic, she suddenly stopped and clutched her side. The head of the hospital, who’d been showing her around, gave her his arm for support. She tried to take another step, but the floor was far away and the walls were spinning.

She woke up in her own bed in the palace. Her husband was leaning over her. She had never seen tears in Rainier’s eyes before, and she reached up to wipe them away. But he caught her fingers and pressed his lips to them.

“How did I get here?” she asked. “What’s the matter with me?”

Rainier looked at her a moment before answering. “Nothing to worry about,” he told her. “But you must get lots of sleep. Doctor’s orders.” His tone seemed too cheerful—just like the doctor’s.

A doctor—the same doctor who’d been showing her around the hospital—came in then and gave her an injection. Sleep swirled about her, drawing her down into darkness. She tried to say something to the doctor, to her husband, but the questions froze on her lips as the blackness closed over her.

Once, in the middle of the night, she woke up for a second. Rainier was sitting at her bedside, his head buried in his hands. She tried to speak to him, started to reach out for him, but, again, darkness pulled her back into its center. Now, she was haunted by dreams she could never quite recall upon awakening. The dreams flew together and suddenly she found herself back in her childhood, with Harper Davis . . .

She had met Harper when she was fifteen. It was Christmas Eve, and, as usual, the Kellys were holding open house in their Philadelphia home. People started dropping in early in the afternoon, to see her father and mother, to see her brother Kell, and to see her. And then she saw him. It was as if she had never really seen a boy before.

“Be cool,” she told herself. “Be non-chalant.” But all she could do was stand there and gawk at him, till Kell came to her rescue. Grabbing her elbow firmly and guiding her across to where he was standing, her brother said, “This is my sister Grace.” Thank goodness, he hadn’t introduced her as he usually did, as his kid sister. “And this,” Kell had continued, “is my friend Harper—Harper Davis.”

She had known Harper such a brief time. But that time had been full of happiness, full of sharing . . . Skating in the park, hot chocolate and doughnuts, basketball games, hamburgers-with-onions (fried onions), movies . . .

Then, suddenly, there were no more dates with Harper. His mother had been the one to tell her why: “Harper is ill—dreadfully, incurably ill—with multiple sclerosis,” she’d said.

Every day after that, Grace went to his house, and every night she came home, and all she could do was cry. Soon after this Harper was moved to a hospital, and she and some of his friends saved up and bought him a television set, hoping it would make the pain more bearable, and help pass the time away. But he had so little time. Seven days a week she went to him in the hospital. She talked and smiled. She tried everything to make him just a little happier. Sometimes, for a fleeting second or two, he responded. But most of the time his brown eyes were clouded with pain, and with the knowledge of how and when that pain would end. And watching him waste away, she felt as if she, too, had lost some of her youth.

When Harper died, she felt death a little, too. It seemed that if death could come that suddenly to someone she knew and cared for, if it could strike him down out of nowhere, then it could come to her as suddenly. She grew older but still the presence of death stayed with her . . . She had felt its nearness today, and her fear had grown to immense proportions since the doctor had told her—yet not told her—what was wrong with her, what had caused the awful pains in her side. She found herself gripping her side tightly now. The pain had returned.

In the morning she saw the doctor and a nurse and her husband standing by her bed. Their backs were to her, but she heard what they were saying. “Immediate operation . . . Lausanne . . . heavy sedation . . .” She tried to interrupt: “Why Lausanne?” The words formed in her head but somehow they didn’t pass her lips. Another word flickered feebly, “cancer,” and then it, too, was snuffed out.

When she opened her eyes again, she saw her husband smile. “Hello,” she said softly and he smiled again, but she felt he had to force himself to look cheerful.

“How am I?” she asked then.

“Fine,” he replied. “But you have appendicitis. They’re going to take you to a hospital in Lausanne today and operate. They say it’s best.”

She wanted to say, “Why Lausanne?” She wanted to say, “Are they sure?” But the anxiety and fear in his face made her save her questions.

Then the nurse and the doctor came back and gave her another injection, and she knew nothing until the next morning.

At exactly 8 am. on the morning of March 4th, 1959, she was wheeled into the main operating room of Lausanne’s Cecil Clinic. She recognized Dr. Lehman behind his white surgical mask. He smiled at her and introduced her to Dr. James David Buffat, the physician who was to assist him in the operation.

Then she was looking up into the powerful reflector lamp and Dr. Charles Bovay, a Swiss specialist, was giving her a total anesthetic. She started to say, “Are you sure . . .” but then the anesthesia took effect, and she knew nothing, until she looked up into her husband’s face.

Why, he’s growing a beard again, she thought, looking at the stubble all over his face, and then: What a funny thing to think of now.

When he saw her open her eyes, he bent down and kissed her lightly on the cheek. “It’s all over, darling,” he said.

“How long was I away?” she asked.

“It seemed like days,” he told her, “but actually it was only a little over an hour.”

“Was it . . .” she started to ask, but her husband broke in.

“You’re fine,” he said. “The operation was simply appendicitis and nothing else. That’s what the doctor told me.”

“Then there was a question?”

Rainier said nothing; he didn’t have to. The way he couldn’t meet her eyes was answer enough.

Suddenly she laughed and broke the silence. “You know what?” she announced. “I feel wonderful!” And she reached up and kissed him as if she had never expected to be able to kiss him again.

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE SEPTEMBER 1959