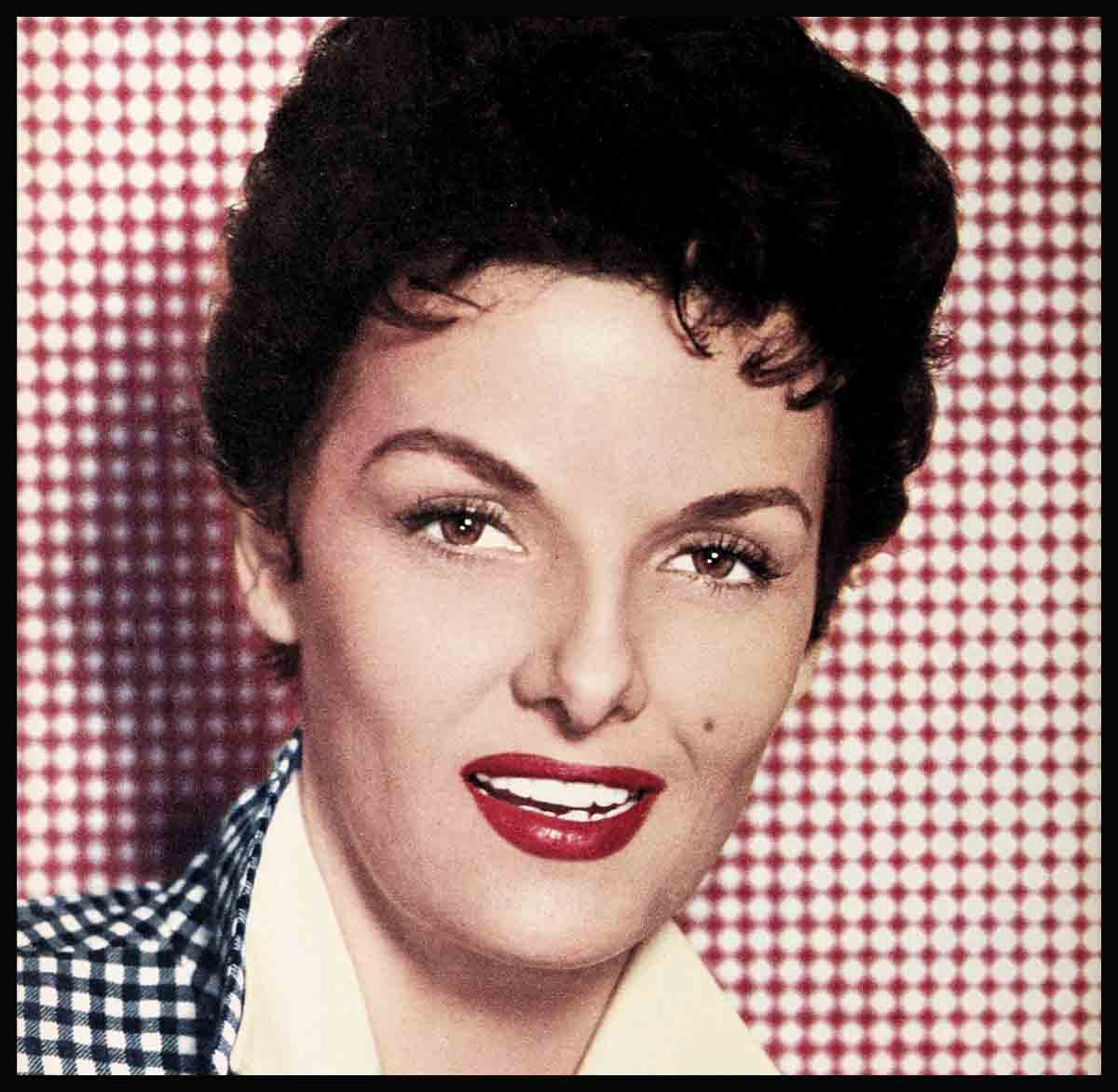

The Terrible Tempered Temptress—Jane Russell

One day in Little Rock, Arkansas, where Jane Russell was making a personal appearance, her friend, RKO publicist Edith Lynch, happened into a conversation with a local citizen who was speaking her thoughts on the visiting star. “Isn’t it dreadful that she was permitted to adopt those two children?” the woman was saying.

“Why is it so dreadful?” asked Edie.

“You know,” said the woman. “A Hollywood star—and especially that type of person. . .”

Since Edie is a lady, she kept her clenched fists at her sides. “Just what kind of a person is Jane Russell?” she inquired.

“Well . . .” A neatly penciled eyebrow went up. “You know!”

“Yes,” said Edie. “I know. And I’d certainly like to tell you.”

Edie’s talking time was limited because of a crowded studio travel schedule; otherwise, she might still be on her soap box in Little Rock. However, when she finished her speech, Edie found herself on the receiving end of an apology. “I’m awfully glad you told me,” the woman concluded. “Isn’t it a shame that everyone doesn’t know these things about Jane Russell?”

If this were so, it might mean considerably less wear and tear on Edie’s vocal chords. However, Jane’s children—Tracy and Tommy Waterfield—are the ones who count the most, and there’s no doubt in their minds that Mother Jane is a gem. Someday, when they grow up, they’ll discover just how she got that way.

They’ll understand why she takes them down the mountainside to Grandma Waterfield’s as often as she does . . . why the frequent visits to Russellville—the 3½-acre property owned by Jane’s family—where a dozen or so cousins appear to greet them with, “Come on, Tracy and Tommy, grab a stick and let’s go!”

The Waterfield children are going to have the same kind of childhood Jane had. They’ll be surrounded by grandparents, aunts, uncles and a flock of other assorted relatives. They’ll laugh and play and fight with their dozen cousins and learn to hold their own. They’ll know what Jane calls “the fabulous security” that comes with the give and take and all-encompassing love of a large family. And friends of the Russells will tell you that the results are worth the occasional bruised shins.

It’s a fact that Mother is a top screen siren. It’s also a fact that Mother is not impressed. Like many stars, Jane Russell asked for fame—though some who know her ofttimes sharp, impatient ways claim she probably even signed her contract with the back of her hand. Nevertheless, fame she got. Bowing, scraping, awed and curious stares she also got. Unlike many stars, Jane wasn’t having any of that. She still isn’t. “If I’m not impressed with what I am, why should anyone else be?”

It’s been that way from the beginning—ever since a photographer sent her picture to Howard Hughes, who was searching for a girl to play the lead in “The Outlaw.” Jane never actually thought she stood a chance. When the word came, it was Ma Russell who answered the phone. Ma Russell had never heard of Howard Hughes. Daughter Jane, she said, was at her cousin’s house, helping gather eggs. “She’ll be back Thursday,” she told him. “Maybe.”

The lead was Jane’s. But there was no flag-waving, and nobody sent up rockets in the Russell front yard. “To Jane and Mother and all the rest of us,” remembers her youngest brother, Wally, “it was just something the Lord sent along. And we wondered how long it was going to last.”

Salary-wise, there was no fabulous deal. And it was almost like any other job—until the poster art began to flood the country and the public began to react. “I couldn’t seem to go anywhere and be myself any more,” Jane recalls. And she cordially despised the idea.

During those years, one oceanside ball-room was all the rage. The big-name bands played there and the young people turned out in droves. As a high-school girl, Jane had a ball there. As a movie star, she was either mobbed or stared into an early departure.

The ballroom was a large, loud place where you had to shout to be heard. And when you shouted, everybody heard. Came the evening everyone heard, “Hey, get a load of that blond over there. Isn’t she the most peculiar-looking sight?”

The peculiar-looking blond lifted a whitened eyebrow. Her partner glanced down at her. “You do look sort of like a creep tonight,” he told her tenderly. Then they stood there and shook, not from dancing but from laughing.

When the blond reached home, she removed her wig and glared into the mirror. Glaring back at her was, you guessed it, brand-new movie star Jane Russell. “Maybe I should have my nose changed,” she grinned at the reflection.

Eventually, as another sort of defense, Jane channeled her energies into what is known as the Russell type of terrible temper—reserved especially for those who, in one way or another, ask for it.

Carmen Nesbitt, who’s been Jane’s stand-in and close friend for eight years, got her first glimpse of it when they met on the set of “The Paleface.” A star-conscious executive introduced them.

“Miss Russell, this is Carmen Nesbitt,” he said.

“Jane,” murmured Miss Russell.

“Carmen, this is Miss Russell,” he went on.

“Jane,” muttered Miss Russell more distinctly.

“And now Miss Russell, if you’ll—”

He got no further. “My name is Jane!” the star of the show howled. “And I darned well want to be called Jane.”

“The Paleface” was Jane’s third picture. Since then she’s made a lot of them. But she is still embarrassed by pomp and ceremony. She knows that the tricks of the trade made her a star, yet she dies a little at the thought of them. She realizes it’s her job to be a glamour girl when “on stage.” Still, when not making a personal appearance, she dresses casually and never fusses with make-up, except for lipstick and mascara. She wouldn’t be caught dead without mascara.

Jane looks at other stars in amazement, when they’re dressed to the teeth. She admires them for it, but she can’t do it. It’s like her Aunt Ernestine used to say when the Russell clan gathered to go someplace. “Why should we get all gussied up? They’re lucky to know us!”

In effect, she was saying, “This is the way we are. You like us this way or you don’t.” The philosophy has followed Jane. She can’t quite get over being amused by the glamour bit.

Hand her a compliment and she responds with a gracious, “Awwwww.” Don’t wait for her to arrive for an appearance in a long, black limousine and step out like a queen. When she’s leaving town on business, she’ll take a ride to the airport in a studio car. Otherwise, she wheels her own way through traffic, gets where she’s going on time, does what she’s supposed to do, and then gets out.

Tell a funny story about Jane and she loves it. Primarily because it lets people know that she doesn’t take herself too seriously. And she surrounds herself with people who seem to take almost nothing seriously.

The Marx Brothers would find themselves completely at home in her dressing room. There, “Shotgun,” Jane’s make-up man, pauses with the powder puff to answer the phone: “Yellow Cab. Where are ya and whaddaya want?”

Or maybe the script girl walks in and says, “You have long lines in the next scene. You’d better concentrate and get them right.”

“Yeah?” says Jane.

“Yeah,” says the script girl. “The first line is ‘Bah.’ The other is, ‘I said Bah!’ ”

On the set Jane goes along with a gag—often too readily. In 20th’s “The Tall Men,” there was a scene in which Clark Gable was supposed to pick her up and toss her lightly across his shoulder. Before the action began, someone figured a forty-pound weight wouldn’t be noticed if hidden beneath Jane’s cape, and it would be a dandy joke on her co-star. Jane heartily agreed.

When the time came, Gable managed to toss her across his shoulder, but with no great ease. He launched into his dialogue and, as he stood there, his face got red and he began to perspire. Everyone began to snicker at the sight. Except Gable—and conspirator Russell. Her face was getting red, too. From holding onto the weight for dear life.

Jane’s informality isn’t restricted to the set; she takes it home with her. And if you stand on ceremony around the lady, you’ll be standing alone. As one friend puts it, “The first time you visit the Waterfields, you ring the doorbell. Seems logical enough. But after a while you realize you may be on the doorstep all day. Maybe somebody will come and maybe somebody won’t. On the second visit, you know to walk right in. Sooner or later you’ll see signs of life.”

By the same token, once inside, if you want a cup of coffee, you go to the kitchen and put the water on. If you’re hungry, you apply your arm to the icebox door.

Jane states her own case. “I’m the kind of a person who, if I know somebody well, will walk right up to the icebox and make myself at home.”

Her chums are equally as casual, even if they haven’t seen one another for years. They never write. When they meet again, they simply take up the friendship where it left off. “Why should anything be different?” asks Jane.

Once she was scheduled to make a personal appearance in Birmingham, Alabama. Before departing, she stopped by an office at RKO. “I’ve got some friends in Georgia, Doris and Charlie Taylor,” she told them. “Let’s send them a wire. Maybe they’ll come over.”

“How far is it?” she was asked.

“I dunno,” replied Jane in her offhand way. “But if they can come they will.”

The wire was sent. However, when Jane and Edie Lynch reached Birmingham, there was no word from the Taylors. Going down to the lobby, Edie passed a man standing in a doorway. “Hello there,” he said amiably.

She glanced in his direction and saw a woman and a baby in the room behind him. “You wouldn’t be Charlie Taylor, would you?” she asked.

“You must be Edie,” he grinned. “Come in and sit down.”

She did. They’d been talking like lifelong buddies for an hour before Edie was struck by a sudden thought. “Good grief,” she exclaimed. “Jane doesn’t know you’re here yet.”

Jane was the last to know. She happened to find out when she strolled by on her way to the lobby to look for Edie.

Jane has a theory about friends. You have friends, you keep them. “Too many children go up the ladder pushing friends away, giving too much importance to fame and money,” she says. “And when they get to the top what have they got? They’ve kicked aside everything that means anything. If they’d only realize. . . .”

If anything, Jane’s taken her friends with her. Her best chums of today are the ones she knew in high school. And the way she frets and worries about them, you’d think they’d never graduated.

When Jane goes out of town on business, there’s always a friend in tow. A friend, Jane figures, who needs a vacation with expenses paid by the studio. It’s customary for a star to take along a secretary, however, Jane’s never given the idea much thought. Consequently, her friends have enjoyed extensive vacations all over the United States and Europe.

The Russell attitude of today is nothing new. When Jane was in grammar school, her teacher paid a visit to Ma Russell. She wanted to know what Jane was like at home, how she occupied her time. “She helps me with the boys,” said her mother.

“No wonder. . . .” the teacher mused, remembering how, in school, little Jane constantly ignored her own lessons to help some bewildered student.

As Jane grew older, she wanted nothing more than to study dramatics with the famed Madame Ouspenskaya, and she pleaded with her mother night and day to let her do it. Ouspenskaya it had to be; no one else would do.

Finally. because Ouspenskaya was the greatest, her mother consented and gave Jane the tuition to take to the Ouspenskaya studio.

It must be said in Jane’s defense that she started on her way to enroll. But on the way, she remembered that a friend, Pat Dawson, was attending another school. Jane decided to stop by and see her. When she left, she still considered Ouspenskaya the greatest. However, Jane had enrolled at the other school—to be with her friend.

“When she came home that night, she laid the linen out in front of Ma,” grins brother Wally. “There was quite a row!”

When Jane blows her top, there’s usually a good reason, though often it’s not terribly apparent. This leaves the cause to be traced—quite possibly on a map. “A friend calls her from Palo Alto,” explains Edie Lynch. “She’s got troubles and she’s upset. So Jane gets upset in Hollywood.”

“Jane goes completely overboard for everybody else, all the time,” says Wally Russell. “I remember one day she blew the roof off the studio because a cameraman was pulled off a job for a silly reason, and he couldn’t defend himself.

“Something like that hits her. She told them if they didn’t have the man back on the set by morning, she wouldn’t come either.” And she meant it.

Although she works in movies because she likes to, Jane’s pictures are sandwiched in between her other activities. And if she never made another film, she’d survive quite nicely.

Just as Jane’s friends were (and are) a vital part of her life before pictures, the same may be said for her religion. “Only now,” moans one friend, “the stories make her look like a junior Aimee Semple McPherson.”

Jane is religious, but so are a lot of other people, she figures. And why the fuss? “I know I’ve been criticized for what seems to be a reversal of behavior,” she says. “But has anyone stopped to realize that I might have always been this way?”

She’s backed by brother Wally. “Mom started us off in church when we were still in our cribs,” he says. “Jane was a baby in Mom’s arms when she first started attending. When the next one of us came along, he went to church in Mom’s arms and Jane was transferred to a clothes basket—and so on as the family increased, until we all graduated to the benches.”

That’s the way it started. And if you go back to Jane’s childhood, you’ll find a good many explanations for the movie star of today, also the mother of today.

The Russell kids—Jane, Tom, Kenny, Jamie, and Wally—grew up in the San Fernando Valley. For a time, the family had a ranch—a cow, four horses, a tractor and an alfalfa field, among many other worldly possessions.

Their father was general manager of the Andrew Jergens Company for the entire West Coast. He did well. During the Depression, he bought a $35,000 home—five bedrooms, a three-car garage and maid’s quarters included. Today Ma Russell, the Russell boys, their wives and families live in what used to be the citrus grove of the estate. The rest of the property was sold because there was no money to keep it up after Mr. Russell’s death.

It hasn’t been so long ago that the valley was all farmland. The Russell kids went to grammar school barefoot and on horseback. Sometimes after school they’d stop off and slide down haystacks—until the owner came after them waving a shotgun. Other times, they’d ride through a melon patch and treat themselves to a snack out of the middle of the field. “We knew it wasn’t right,” says Jane. “And we’d get awfully sick.”

They’d come home reeling and Ma Russell would know exactly what had happened. She’d stand and look at them and wait. They’d stand and look at her and plead, “Give us a licking, Ma. Then you go tell Mr. Gilbert and give him some money. Please, Ma, can’t we have a licking?”

Ma Russell would remain firm. So off they’d troop to Mr. Gilbert’s door. “We stole your melons,” they’d confess. “The Lord made us sick and we want to get well. So we had to come back and tell you. We’ll work until we can pay for them.”

Today, if Jane does something wrong, intentionally or unintentionally, she still knows that she’s got to go back and make it right. It may be, “I hurt you the other day. I was rude and I’m sorry.” No matter what it is, for Jane, the balance has to be kept even.

If someone wrongs Jane, she proves more tolerant than anyone. In these days when exposé magazines are selling like hotcakes, she hasn’t been ignored. Her friends have been aghast at her calm manner. “You ought to take that writer’s head off,” they’ve told her.

“Why?” asks Jane. “Poor guy. I feel sorry for him. Something must be the matter with someone who’d do a thing like that.”

Jane was sixteen when her father died. She was the only daughter and they’d been particularly close. She was a long time getting over his death.

She was sixteen, an age at which both parents’ wisdom is especially needed to cope with offspring who are no longer children but are not yet adults. Jane had reached the age at which kids were beginning to smoke and drink and run wild.

Ma Russell prayed for the youngsters—her own and all the rest. She also took action. She kept Cokes on ice, coffee hot, sandwiches in the icebox. She offered food for thought as well—understanding that they seemed to be unable to find elsewhere. And they came to her.

That was the beginning of the now famed chapel. At first, the meetings were held in the Russell living room. At first, they weren’t even considered meetings—just get-togethers for coffee and conversation and the hashing out of problems. And Ma Russell would slip in a prayer.

The crowd grew, And, as the youngsters grew, they found they still needed Ma’s understanding and her prayers. Through high school, through the war years—for that matter, throughout their lives. It was after World War II that the “congregation” constructed the chapel.

As for the handling of her four younger brothers, Jane did the honors—quite often with her fists. For a time, every family argument would end in a front-yard fight, with sister the victor. But as does happen, the younger brothers eventually began to tower over big sister. “One day,” Wally remembers, “there was a bigger row than usual on the lawn. And this was no verbal argument. That’s when Jane found out she had to change her tactics. The time had passed when she could tell us to do something and if we didn’t she would knock us down. Now she had to turn on the charm and make us feel very important—as if doing what she wanted us to do was our own idea.

“But the time to back away still is when she’s coming at you like a dove,” Wally adds, grinning. “You don’t know whether she’s going to pat you on the back or beat you over the head!”

The worst verbal lashing of all came after Jane had signed her contract with Hughes. She had to have a car to get to work and she bought a convertible.

At this particular time, brother Kenny was dating a girl in Riverside—the girl he later married. But this particular night was the one before he was due to report to the Navy. He wanted to see his girl. The problem was how to get to Riverside.

Two Russell heads got together on the matter. “Kenny and I set the alarm clock for 11 P.M.,” says Wally. “Everyone was asleep by then and we slipped out to the garage.”

Jane had obligingly left the keys in the car and the boys released the brake and pushed her beloved new possession out of he garage and about a half-mile down the road. Then they hopped in and roared away to Riverside.

Next morning, Jane went out to her car. It had rained the night before, and the convertible was spattered with mud from top to bottom. She checked the gas. The tank had been drained. “Did the fur ever fly that day,” Wally shudders.

However, sister Jane was also capable of giving the boys invaluable advice. “We’d be all shook up over a girlfriend,” says Wally. “A girl would give one of us the brush and he’d be miserable.”

That’s when Jane would sit the un-happy fellow down for a talk. “A girl will fight you every inch of the way until she can dominate you,” she’d tell him. “And if she can—well, then she won’t think much of you.”

“When we got to high school,” says Wally, “we found she’d given us a good head start on a lot of guys who had to find it out the hard way.”

Yet there were times in “fighting Jane Russell’s” life when she couldn’t fight—and advice didn’t help. She couldn’t do battle with nature, and her first three years of high school were miserable ones. She was tall and thin as a board. She never wore sleeveless dresses because her arms were too skinny. And she took a terrible teasing. “They called me Bean Pole,” she says. “And it hurt.”

Jane has never forgotten those painful years. That is why when she sees someone in a turmoil—someone who can’t do anything about it—she’ll pull the head off the person responsible if he comes into sight. “Children who haven’t had something to overcome when they’re young—no matter how minor—are bound to be less tolerant of other people’s problems when they grow up,” she says. “When a person who’s never been sick sees someone ill, they’ll say, ‘You’re sick? That’s too bad.’ But they really don’t know how it feels because they’ve never been that way.” If Jane’s been that way and found the going tough, she’ll lose no time in smoothing the road for others.

For example, on a trip to Europe in 1951, Jane discovered the disappointment of being unable to adopt a child. She’d found a little boy in Germany who was eligible for adoption and she wanted to bring him home. But the red tape of immigration restrictions blocked her.

Then she got to thinking of the vast numbers of other couples whose names were on long waiting lists back in the States—and the many European orphans who were available for adoption but could find no homes in their own countries.

On her way back to Hollywood, Jane stopped in Washington, D.C., where she haunted Congressmen about the matter. When she left, they’d promised action. As a result, more children than ever before are now able to enter this country for adoption. Going a step further, Jane helped found WAIF (Women’s Auxiliary International Fund), which has become a division of International Social Service, which helps place the children.

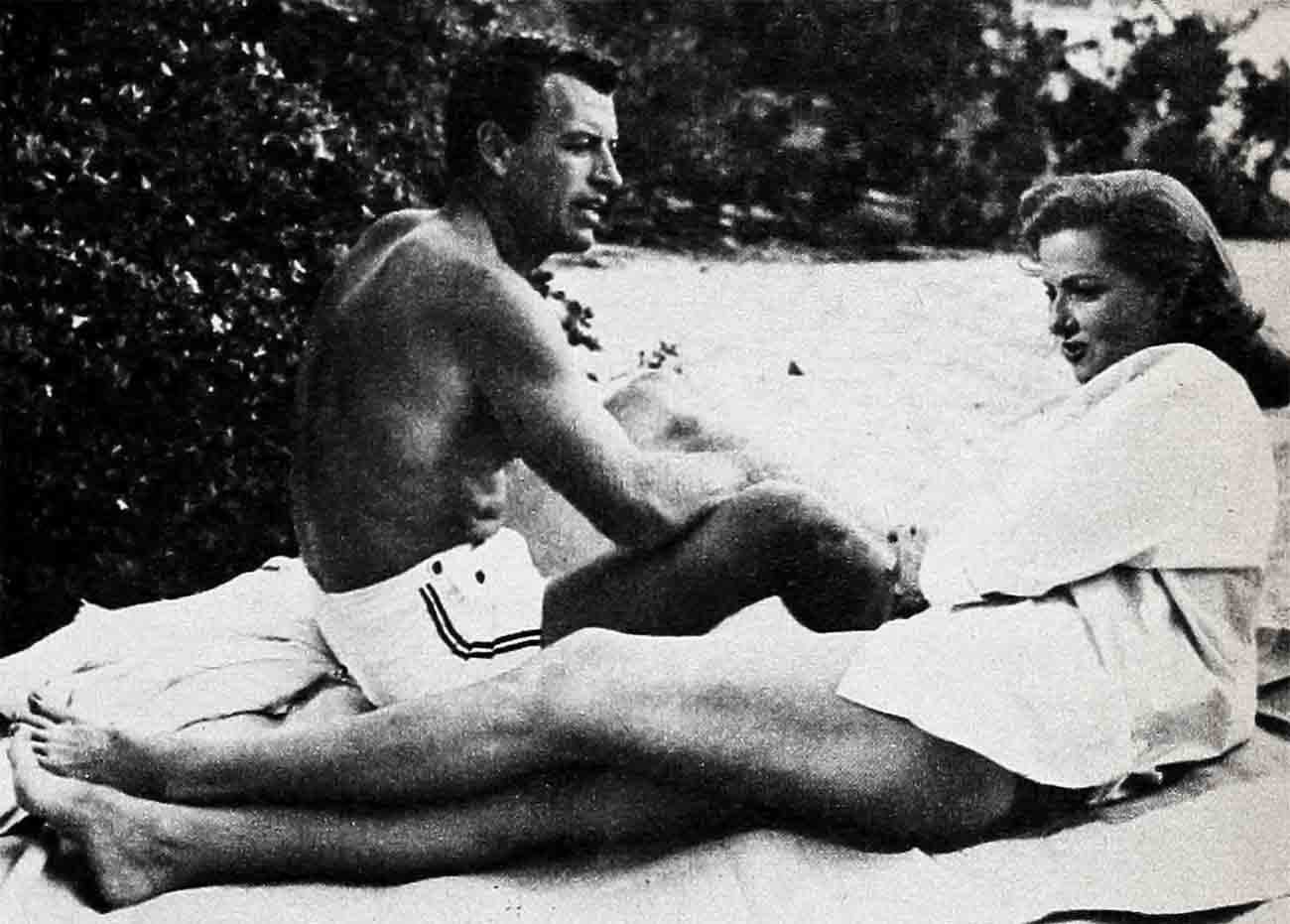

Jane also knows the rocky road of love, despite the fact that she has one of the happiest marriages in Hollywood. Her suffering occurred when she first fell in love with Bob Waterfield. They went to the same school and, whenever he’d walk by, her jaw would drop. But he always walked by, never stopped.

After Jane grew up a bit—a considerable bit—Bob noticed her, they began dating, and fighting. “He’d come over to the house to see her every evening or so,” remembers Wally. “They’d roll back the rugs and put some records on.

“Being the youngest, I had to go to bed early. But I used to be awakened by doors slamming and Bob’s car charging off. He left in that fashion just as many times as he went out peacefully.”

After “The Outlaw,” Bob took a kidding from his friends at UCLA. “Jane’s a movie star now,” they’d hoot. “Gee, Waterfield, you’d better throw in the towel.”

At first Bob paid little attention. “Just so we could go out on dates every evening,” says Jane. “But the nonsense on the outside began to bother him, too.

“He likes to go along quietly and mind his own business. He used to take me to the beach all the time. We have a beach house now, but he still likes to go down to a public beach. Only he won’t take me!”

They were married after Jane handed him an ultimatum. “We get married or we both start dating other people.” Robert accepted her proposal.

A short time later, Bob went into the Army and Jane followed him to Georgia, going on suspension to make the trip. That meant no weekly check and since Bob’s Army pay was meager, Jane went to work in a beauty parlor in Columbus. “You, Jane Russell, working in a beauty shop?” customers would gasp. “But why, honey?”

“But honey, why not?” was Jane’s reply. “We need the money.”

Back in Hollywood, after the war, times were better. Waterfield became an all-time great in professional football; Jane’s career began to go great guns. First of all, however, she was Mrs. Waterfield, football wife.

Bob was most at ease around football players, so there were always football players and their spouses around the Waterfield home. They’d be sitting in the living room of an evening and Mrs. Waterfield might venture to remark that sometime she’d like to vacation in Minnesota, where she was born. “Minnesota?” Eyes lit up. “Say, remember the Minnesota-Illinois game?”

Mrs. Waterfield had prompted an evening-long conversation. Every quarter of the game was replayed while Jane’s head went back and forth as if watching a tennis match. “They did? Really? They did?”

The Waterfield marriage is noted as an amazing one because they’ve always seemed to have had little in common. It’s also been said that Bob and Jane’s family don’t get along at all.

Actually, the Russells and Bob Waterfield like one another tremendously, and also have great respect for one another. Bob doesn’t like crowds; the Russells add up to a mob. A noisy group makes Bob nervous; the Russells can make more noise than a New Year’s Eve crowd in Times Square. When he can take it no longer, Bob politely ducks out.

Jane doesn’t mind. The Russells understand. “He’s something like Dad used to be,” says Wally. “He wants the peace kept.” So it’s live and let live, and everybody’s happy.

The Russell clan goes on its hectic way, and Jane remains close to the folks, who now total some twenty-two—“Russellville” being somewhat of a community in itself. Little Tracy’s and Tommy’s cousins now number thirteen.

One of the Waterfield kids’ greatest treats is being allowed to stay overnight, or perhaps spend several days with their cousins. And Jane drops in, with or without her children as often as she can. Sometimes she stays only ten minutes, on her way home from the studio. And there’s no telling what she’ll be sending next. “She’ll pose with something,” says Wally. “And because it’s a custom to give the star the product, she gets whatever it is. So she’ll hand them a card with an address to send it to.

“One time she posed with a TV set, a real dandy. It arrived at Pam’s and Jamie’s house a few days later.

“She may mention something’s coming,” Wally adds, “but that’s only because we might think there’s a mixup in delivery and send it back. She hardly ever says what it’s going to be. But you can bet your life she tells us where it will look best in the house.”

Jane still gives her brothers advice. One night she visited Wally’s new home. She walked into the living room and muttered, “It’s all wrong.”

Then she completely rearranged the room. When she’d finished she stood back and looked at it. “Yep, that’s it,” she said, and went away.

Wally wasn’t sure he cared for the arrangement. He stared for a while then moved everything back.

Several nights later, Jane came to dinner. She stepped into the front room and stopped in her tracks. There was a long pause as she surveyed the changes that had been unmade. “Okay,” she said. “I tried.”

“But if she’d known I didn’t like it and if I had left it that way anyway,” says Wally, “she’d have really gotten mad.”

The Russell brothers recently went into the contracting business, and Jane, as usual, is behind them one hundred percent. She is on hand to advise, of course, and to lend her talents to decorating the finished products. She knows her interior decorations, and the fact that she’s a star has little to do with it.

Actually, the only person Jane has ever wanted to impress is named Waterfield. And with him, she tried not to be her usual modest self. During their courtship days, an engagement ring went back and forth between them. Bob would give it to her, she’d give it back. Came the time when she wanted it again. “I don’t have it anymore,” Bob told her.

Jane wanted to know where it was. “I hocked it to go fishing,” he said.

“Have any luck?” she asked him.

“Nope,” he said.

“Yes, you have,” said the modest Miss Russell. “You still have me. Me, I’m a jewel.”

The lady had something there. But if you try and tell her, it’s likely you’ll get the gracious, “Awwww.” That—or a belt in the head.

THE END

—BY ELIZABETH WISE

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE JUNE 1956