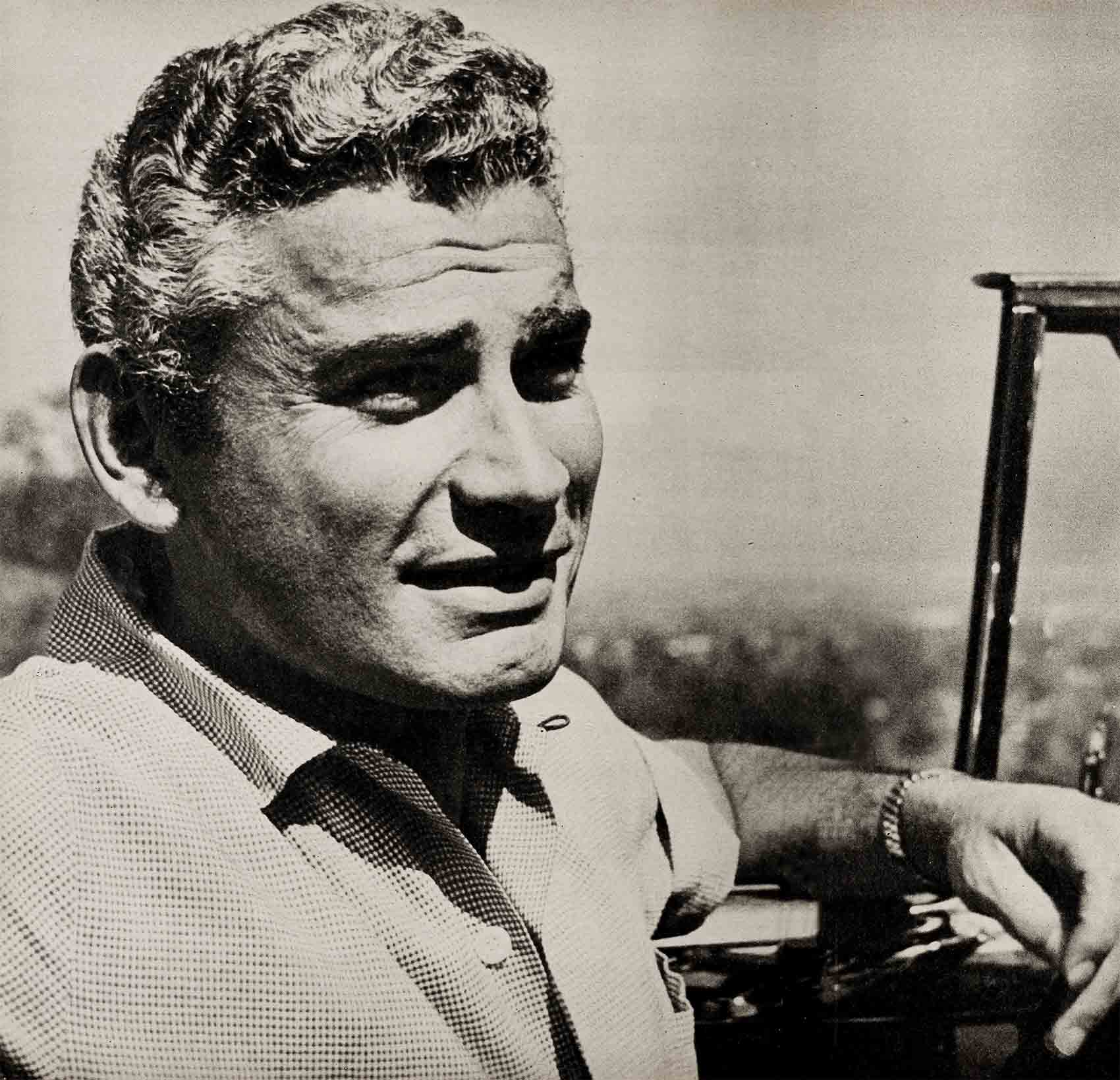

The Lonesome Road—Jeff Chandler

A curly-haired giant of eighteen stopped mowing his lawn in Long Branch, New Jersey, sat on the porch steps and feverishly scribbled notes for the novel he was planning. Little did he know that he would live it instead.

The hero of that yet unwritten book was a young man who had everything. He was big, strong and athletic. He was handsome, forceful and magnetic. He had a fine mind and many talents. He could sing, paint, act, write—there was hardly a gift he did not possess.

So he went forth into the world and, talent by talent, sought recognition. Each time he almost succeeded, but not quite: always when the goal was at his fingertips he lost it. Finally at thirty-five, he looked back on his disappointments and decided he was a failure. Then something happened which brought him a satisfying realization and inner peace: Although fame had escaped him, still he was fulfilled. Success was in the striving.

The boy, named Ira Grossel, never wrote that book. The hero, of course, was himself. The theme stuck with him. Today he calls himself Jeff Chandler. And at thirty-five, although he is already a busy and famous Hollywood star earning $3000 a week, he is restlessly and ambitiously pushing every one of his talents.

Jeff has embarked on the long shot, uphill career of a popular crooner.

He has organized Jeff Chandler Enterprises to produce his own pictures when his contract expires.

He is working on a nightclub act.

He is preparing a radio serial based on the files of a big metropolitan newspaper, in which he will star. Later he will adapt it for television.

He is writing and sketching ideas for Jeff Chandler adventure publications.

This flurry of ambitious activity is a matter of curious speculation both among the people who know him and those who don’t. It has coincided with the breakup of his marriage, which looms as a contributing cause. In securing her divorce from Jeff last April, Marjorie stated in her plea: “As a result of his complete and continuous absorption in his career, he was not a companion in any way. . . . He was chronically fatigued so that he would fall asleep wherever we were. . . .”

Jeff himself allows that the reason he is pushing himself to the limit is to make more money. “I decided to be an actor when I was fourteen years old,” he says, “because I’d heard they made $5000 a week. I still want to make that kind of money. I have responsibilities to my family. I want enough to be able to retire and relax when I’m forty. That gives me five years. I’m not sure I’ll make it.”

Jeff’s agent, a dapper little man named Meyer Mishkin, whose office adjoins Jeff’s, has a different explanation. “Jeff is just naturally a terrific bundle of talent,” he says. “He’s easy, sure-fire, no temperament, no trouble. Why shouldn’t he spread himself? He just likes to work.”

But there is another reason why Jeff Chandler is striking out in all directions at an age when he thought he’d be philosophically looking back at his struggles. He can’t believe he’s a success until he makes the best of everything that’s in him—and that, in his own opinion, is quite a lot.

This is not conceit. Jeff Chandler is humble about his good fortune. His favorite phrase about himself is still “the luckiest kid on the block.” At his studio he is known as a “sweetheart” to work with, serious, conscientious, prompt and ready, and exhibiting no temperament since he grunted imperiously, “I am Cochise,” and became a star. He still bends over backward in a-self-effacing manner both with his associates and his admirers. “Jeff always talks as if he’s asking me a big favor to help him out on a deal,” marvels Meyer Mishkin. “I have to ask him, ‘What am I for, anyway?’ ”

His self-consciousness about what others think about him is demonstrated constantly. Once, when Jeff was making $800 a week, an interviewer wanted to take his salary and break it down for an article, showing how taxes, fees and expenses shriveled that sum down to almost nothing for Jeff to keep. Jeff considered the idea briefly, then shook his massive head. “If you were making $50 a week and read about poor me making $800,” he asked the writer, “would you cry for me?”

After he had separated from his wife, another reporter tried to get Jeff’s opinions on what qualities he admired in women. Again Jeff pondered and begged off. His reason: the qualifications of such a dream girl might imply they were those which his wife had lacked.

“I like being a celebrity,” he’ll tell you candidly. “I like being recognized. Except, of course, by guys like our aforementioned ginned-up friend.”

Jeff Chandler always says what comes into his mind, and often answers questions as though he were talking to himself. He takes time to think before he replies and then he gives an honest answer. Explaining his drive for success, he says that from the time he was an awkward, overgrown kid in East Flatbush, Brooklyn, he always believed that he towered not only physically but in destiny, too, above the other kids, although he was at least as poor as the rest.

That feeling of being apart and having a special superiority is common to all actors in some degree. Maybe it helps them to act. In spite of Jeff’s faith in his own powers, he has great humility. It is no inferiority complex however. He has been unhappy only when he has been prevented from doing everything he thought he was naturally equipped to do.

Jeff has had an oversized physique and bold, impressive features since he was a tot. Today he is a kingsized man—six feet, four, 210 pounds, 13 shoe, size 7 5/8 hat. Once when his agent suggested him for a romantic leading man role, the reply he got was, “Jeff Chandler? He’s a mug. But I’ve got another job in mind for him. If I can’t get the plug-ugly I want, I’ll call you.”

Jeff has a regal bearing, moves easily, and his deep bass voice comes out softly. He uses meticulous grammar, not slang. When he wore a toga for Sign Of The Pagan he looked as though he had stepped out of the ruins of ancient Rome. The Indian chief “Cochise” in Broken Arrow missed an Academy Award by three votes. But it was this same strength, suggesting leadership, that gave Jeff Chandler his first movie break as the stoic Israeli in Sword In The Desert. In his radio acting days, Jeff had been called on no less than seven times to play the Christus role. There is no small doubt that Jeff Chandler, consciously or subconsciously, believes himself specially gifted and destined.

Jeff Chandler was born in Brooklyn, and he lived most of his boyhood in a moderate neighborhood, on East 37th Street. His father and mother were separated when he was three and he grew up in a house with his grandparents and an aunt and uncle. He was an only son, and a fatherless one. He thinks perhaps his burning desire to distinguish himself stems from need for love from his father.

Despite his size and his environment, young Ira Grossel was no roughneck. “I suspect I was lucky,” he says. “Because I was big the kids left me alone. It was a good thing. I was not aggressive or belligerent. Maybe by their standards I was a sissy. I don’t know. I remember we lived once across the street from a family of five boys, all rough and tough. I used to cross the street before I came to their house. One day I forgot and ran head on into the most hardboiled one. To my great surprise—and relief—he quickly crossed the street. Later, they told me that all the time I was afraid of them, they were afraid of me!”

Jeff Chandler has never hit a man in his life, except for his faked scripts for the cameras. He learned to box for The Iron Man but he would rather remain a spectator. And while he played some football and basketball in school his real joy in sports is baseball: He played sand lot ball all his youth and became a fervent fan.

All his life Jeff Chandler has had ambitions, interests and desires that had no connection with his naturally husky body. He traveled a lonely path as a boy and he still travels it as a man, prodded on by a feeling of obligation and guilt. “I’m still not up to what I’ve become,” he observes at times, adding cryptically, “and yet what I’ve become isn’t enough for what I should be.”

Frugality is so ingrained in Jeff that his happiness over a good trade or bargain sometimes backfires.

Jeff was having dinner with a girl he had known in drama school fourteen years ago, now happily married in the East and visiting Hollywood for the first time. It happened that he had recently acquired his first Cadillac, a distress sale car which he got at a sizable discount. Excited about it, he mentioned the price to his friend—only $4,300 for a $5,300 car.

“Why,” she exclaimed, “the down-payment on our house was a lot less than that!” The thrill of the new car was destroyed and he felt guilty as he drove it home. Jeff’s personal wardrobe is built around six suits he had tailored for his first out-of-costume role in Because Of You only three years ago. He waited until then to properly outfit himself and bought the suits at half-price from his studio. He likes to roam around hardware stores. Not long ago a five-way tool called a shopsmith and priced at $229 caught his eye. He strolled by admiring it for five days, telling himself wistfully, “I wish I could afford it.” One day he stopped still and said aloud, “What am I saying? I can afford it!” So he bought it. Jeff’s business manager is always telling him, “You ought to spend more money!”

Jeff’s thrift flies out the window where others are peat His alimony and support settlement was very generous. Around his studio he is known as a cotton-soft touch. For ten pictures he costarred with actors making twice what he made without a squawk. “Jeff,” says one friend, “wants to own the world—so he can give it away.”

This trait is a hangover from Jeff Chandler’s boyhood, which he perhaps ponders too much. The result is an idealistic, socially conscious, and somewhat conscience-tortured man whose past is always cropping up to influence his present. For instance, although he was an adoring dad to. both his little girls, Jamie and Dana, Jeff could never bring himself to buy them a pet. When he was a little boy his pup got sick and he watched it die, unable to help it. He has shied from owning any kind of pet since.

Jeff Chandler, despite his formidable appearance and assured manner, is a shy, sentimental and self-critical character. That’s why many of the legends about him don’t stand up. The lone wolf idea has been wishfully tacked on him ever since it was known he was having trouble at home. Because Jeff has sought companionship with women (and except for publicity, premiéres and such, they are almost all women he has met professionally or known before) it is widely hinted that he is a quiet but deadly operator in the romance field.

Actually, Jeff Chandler verges on being a social flop—and has been more or less all his life. As Tony Curtis, one of his best friends, says, “You say ‘hello’ to Jeff at a party—and when you try to say ‘goodbye’ he isn’t there.” Publicity people who have tried to pair him with young actresses for Hollywood affairs testify that it’s difficult. Only when-he calls on his good friends, Janet and Tony, Patti and Jerry Lewis, or Sheila and Gordon MacRae (whom he knew way back in his Millpond Playhouse days) are his Visits relaxed and. Easy.

This has been baffling to predatory ladies. Usually they have been kept at a distance despite their persistent efforts.

Jeff is no hermit nor has he ever -been, although he says “I’m not even thinking about marriage again.” He always has been a one-girl man. When prodded about his early romantic dreams he says, “They weren’t romantic, nor adventurous. The dream I had was always the same, It was of a depression kid—like me—meeting and marrying a poor girl and together struggling out of poverty and obscurity to riches and high position.” That, in effect, is the dream that he made come true—only to lose it—and ironically because of the struggle. There are so many reasons for every marriage failure that no one can pinpoint a single cause. Jeff’s boyhood can supply a clue. Even then his all-absorbing devotion to one particular responsibility caused other responsibilities to suffer, quite without intention.

Until he was a sophomore in high school he was a leader at school, wrapped up in a dozen activities and outlets that he enjoyed. But that year his grandfather’s slow death from cancer, coupled with hard times all around, forced his mother to open a small candy store in their home. Jeff was called on to help out after school. He dropped all his scholastic ambitions and activities. He was a great help to his family, but to do that he abandoned everything else. There are strong hints that this is why Jeff and Marge found their marriage in conflict with his career.

At that divorce hearing, Marjorie Hoshelle said, “We could never come to any agreement or compromise . . . He said he was fond of me but found it impossible to live with me because of the many conflicts . . .” Yet Jeff had known Marge since 1941 when they were both in little theatre work around Illinois. Their romance grew out of two careers. It was Marjorie who helped Jeff learn the Hollywood ropes, bore him two children, shared his life for eight years. Yet the harassments of married life along with those of his professional existence took too high a toll. No other woman nor any other man entered into the rift.

Jeff yearns to have his life perpetually in order. Since he became a star he has tried to discipline himself. He diets religiously and is almost a teetotaler (“Soda pop tastes better”). He dresses more like a broker than an actor. He showers twice a day, keeps his tight, wiry thatch cropped once a week (barbers recently voted him “America’s best male head of hair”). He is meticulous about appointments and worries considerably about a tendency to procrastinate, which business friends say he does not do.

Every day when he is not making a picture and is not out of town, Jeff reports to himself at his office bright and early like any businessman. “I like to play ‘office,’ ” he admits. “It makes me feel I’m accomplishing something.” Jeff’s office is next to Meyer’s and they work as a business team.

His picture scripts are neatly bound in leather on shelves, efficient gadgets are carefully aligned on his desk, his files are in shape and the walls neatly decorated with his various awards, his sketches of baseball heroes and photographs of his two daughters. In one drawer is a carefully stacked pile of the children’s drawings and their notes to him over the years—a crayon coloring labeled “This is a cat” or a bunny effort and the scrawl “To Daddy—for making all Easters very happy.” Jeff has sentimentally saved all these and plans to bind them neatly in books. He sees the girls once a week.

Jeff lives in an apartment in Westwood Village although he’s usually there only to sleep and not often for that. Because he has been racketing off in all directions breaking ground for his projects. Recently he tape-recorded 200 spot announcements to be played by disc jockeys all over the country with his record, which has already reached the 125,000 sale mark and needs only a few thousand more to make him an official hit as a crooner. He has been commuting to San Francisco to raid the Chronicle files for his radio reporter series, due to start in the fall. He has just finished Sign Of The Pagan, one of U-I’s first CinemaScope productions.

This gives Jeff Chandler a program of all work and very little play—but that doesn’t bother him. He never has been able to mix work and play. When Jeff went to Italy for his third picture, Deported, he might as well never have left home. He saw only Naples, where the picture was filmed. He has contemplated no other foreign scenery except the bleak Aleutians where he served two years at a lonely anti-aircraft outpost during his four-year Army service. “Some day,” he occasionally promises himself, “I’m going to take off in a new, car to tour America, all by myself. I’ll go where I please, see what I like and stay as long as I want wherever it’s interesting. I won’t be in a hurry and I won’t give a damn.” That’s probably just talk. The only place Jeff has been known to relax is Apple Valley, up on the Mojave Desert. He hasn’t had any regular exercise since he played right field for the Martin and Lewis “Aristocrats” softball team. His pals seldom suggest tennis or golf any more. They know what he will say: “Too busy.”

“But,” shrugs Jeff Chandler, “you can’t do everything you want and have everything you want at the same time. I don’t know whether everything I’m trying will be a success or a flop. It’s really not important. I do know that if you don’t make a bid for everything you feel you can do, you’re a failure, any way you look at it. You’ve got to get things out of your system. I’ve always wanted to know more about music, I’ve always wanted to sing. If I hadn’t made this record, there would still be plenty of things in my life to fill it. But since I have and there’s a certain success to the effort, why, that makes more things to do and it makes everything else I try easier. Everything could change for me in thirty seconds, but right now I feel that I’m getting somewhere at last.”

That’s a curious statement from a man who has just seen his home break up under the pressure of an expanding career. But Jeff Chandler can’t help himself. This is his last chance to prove to himself what he believed as a boy—that he is different, special, above the crowd. It’s his last chance to write that novel that he plotted years ago, not with a pencil but by living it—but its title might be, The Lonesome Road.

THE END

—BY JIM NEWTON

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE AUGUST 1954