“At Last I Have My Baby”

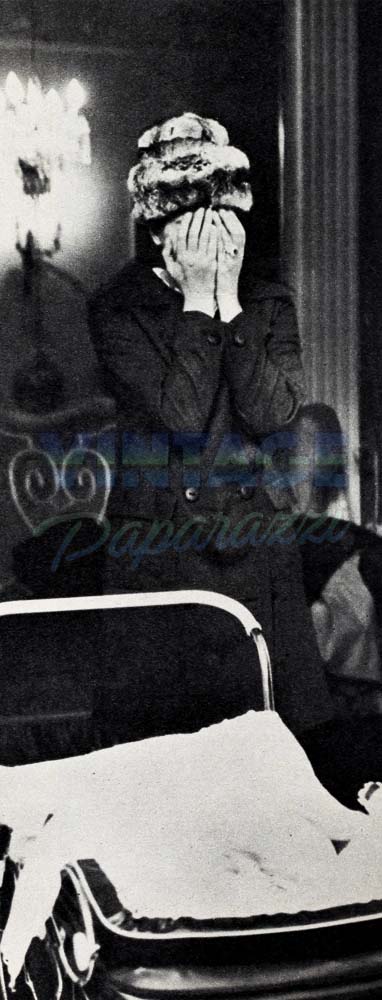

Such a tiny baby! So little, so warm and cuddly in her arms! Sophia Loren held the wee bundle of humanity gently against her own warm woman’s body and looked tenderly into the baby girl’s face.

“At last,” she thought as in a dream. “At last I have my baby.”

With solemn attention she stood before Father Virginio Rotondi and heard the Jesuit priest pronounce the name of the blessed infant in her arms: Alessandria.

When the christening ceremony was over, Sophia sighed and relinquished two-weeks-old Alessandria Maria Romano Mussolini into the waiting arms of her young mother. It had been so lovely, for those few minutes, to dream and pretend that it was her own baby she was holding—her’s and Carlo’s. But of course it was only that—a dream. Little Alessandria belonged to Sophia’s younger sister. To Maria, whom Sophia loved tenderly. Almost, she thought to herself, as much as I love this baby!

From the moment Maria had confided that she and her husband Romano—-son of the late II Duce—were expecting, Sophia too had been eagerly expectant. It was almost as though she were living through Maria, during the months of pregnancy. Not that she envied her little sister—you do not envy those you love, you wish them well. But how she’d have loved a baby of her own! A little, sweet baby.

AUDIO BOOK

And this, of course, was an impossibility. When you are caught and twisted in the coils of the law, so that you don’t know from one day to the next if your husband is your husband, or if you are legally a bigamist or an adulteress—how can you bring a helpless baby into your confused world? Sophia has said as much. “Some day I will have a son,” she once said. “I would like very much to have a son, I wish it with all my womanly heart—the heart of a Southern Italian woman. But I can’t afford to have him now. I know what it means to have an illegitimate birth. How could I inflict such suffering on an innocent creature, my son?” No, this was Maria’s baby. And Maria’s good luck.

Even before this, Maria was the lucky one. Her luck began, rightly enough, with her wedding in March of 1962. Sophia remembered. . . . Maria, radiant, beautiful—walked slowly down the aisle of the carnation-strewn Church of St. Anthony to stand by Romano’s side. Sophia wept—tears of joy. Because her little sister, whom she had raised and mothered, now wore the ecstatic face of a bride . . . a saint.

Mingled with Sophia’s tears of joys were tears of regret, too. For herself. This was what she had always dreamed of, to be married in church like a lady. But the church had maintained that Carlo was still married to his first wife, his civil divorce counted for nothing. And so their wedding day on September 17th, 1957, had been very different from her dream. Carlo in Europe, and she on a Hollywood sound set making a picture, “Desire.” And two lawyers, strangers to her, standing in for her and Carlo in Mexico, at a proxy wedding ceremony. It had been more of a farce than a wedding.

Even today, at this beautiful church wedding of her sister, Carlo could not be present. “They” would not let him. “They” would arrest him if he showed.

So, alone, she watched Romano slip the wedding ring onto Maria’s finger, and she gently felt for her own ring, touched it. She remembered only too well the moment she put it on her hand—alone then, too. She hadn’t known exactly what time it would be proper to begin wearing it, what time she was married in Mexico—not until Louella Parsons telephoned her on the set and said, “Congratulations, Sophia. You were married an hour ago. You are now Mrs. Ponti.” It was only then, after she’d hung up on the phone, that she had fum- bled in her purse, found her wedding hand wrapped in one of her tear-stained handkerchiefs, and slipped it on her finger.

Then, so soon it seemed, Maria was whispering the news—the baby. Sophia put her arms around her sister—carefully, as if she might break, and said, “Brava, and hurry up so that I may take this baby for myself.” She was so excited!

Maria knew what she was trying to say: “Hurry up and have this baby so that I may hold it in my arms and kiss and cuddle it—and sometimes pretend for a few minutes that this soft little thing belongs to me.” That was all she meant! But the columnists, reading the remark in the paper, blew it up into something vicious. She certainly never meant what one of them said—that she planned to adopt the baby herself. Or, as another intimated, that she was going to “kidnap” it.

Ah well, anybody but a columnist could see how happy she was. She went on shopping sprees, came home loaded with tiny clothes, with rattles, toys. She bought the baby a bassinet and a bathinette. Because she was bad on dates and in the store couldn’t remember if the baby was due in February or March, she bought a sled and a football both. When she came home and Carlo told her that football is played in the fail, not in the spring, she laughed—and went out to get a baseball and bat.

But as she opened the new packages to show her treasures to her husband, she could see that something was bothering him. “A glove?” she asked. “Is it that he’ll need a glove?”

Carlo tried to change the subject but she wouldn’t let him, she was determined to wheedle it out of him. She called him by all her endearments: Polpettone (meat loaf) which to her meant “dear,” got her nowhere. Peperone (pepper), her way of saying “dearest,” wouldn’t melt him. At last she threw herself into his lap, flung her arms around his neck and begged, “Suppli, please!” And suppli, which is Sophia’s favorite dish (balls of fried rice and mozzarrella cheese) and is her kind of shorthand for “I love you very much,” did the trick. He told her. He looked at her gravely and asked, “And what if the bambino is a girl?”

Sophia whooped with glee. She ran into the other room, came back carrying dolls—dolls—more dolls. She piled dolls on the sofa around him until Carlo stopped laughing long enough to cry “Finito! Enough!”

The months flew by and then—too soon, I it was not time yet—the baby began to fight its premature way into the world. Sophia sat in the waiting room of the hospital’s maternity wing, but her soul was upstairs with Maria in the delivery room. She suffered as if she were giving birth.

All around her were the fathers-to-be. The first-time fathers paced the floor, grinning shyly as they passed each other and then swiftly resuming their expressions of anxiety, of bewildered helplessness. The veterans, the ones who’d been through the mill before, passed the time playing cards with each other, or reading the papers.

And Sophia? She sat thinking dolefully of the five bambini she had always wanted—she who had none at all. “They won’t let me have a baby,” she said once, tearfully, to a reporter. “They” were the representatives of Church and State who plagued Carlo and herself. Once, just once, she had thought she was pregnant—and had deliberately returned to Rome to face her accusers and straighten out the muddle of her marriage to Carlo. She knew she was risking a five year term in jail but she went. once and for all they must settle the question of whether she and Carlo were legally married—for the sake of her unborn baby.

But no decision was made at the time. Then it no longer mattered. For as fate would have it, she was no longer pregnant.

Now the waiting room door opened and everyone tensed expectantly. A nurse entered and Sophia prepared herself for news, but the woman in white walked by her and went to one of the card players, whispered to him. He leaped to his feet, grinning broadly, and held up seven fingers for the other men to see. One of the first-time fathers turned pale and asked, hoarsely, “Septuplets?” Everyone laughed. “No, no,” said the chosen one, following the nurse from the room. “Now I have seven kids. But this bambina is my first girl!”

Sophia crossed herself. May his baby never know poverty, she prayed. May she never know misery. May she never know shame . . . the shame of being ugly . . . long and skinny and brittle like a strand of uncooked spaghetti . . . of hearing the boys call after her, “Stecchetto,” and knowing they were right, you were a little stick.

The shame of being illegitimate . . . of hearing the girls whisper, “Bastardo! Bastarda!” behind your back . . . of being rejected by your own father . . . of having his wife break in when, aged fourteen, you are trying to get an extra’s job in Cinecitta and have her scream, “No, she is not Sophia Scicolone. Never a Scicolone. She is the daughter of nobody.”

And later, in the marriage where there is so much love, the shame of being branded “adulteress” because you tried to obey the letter of the law by dissolving your so-called “bigamous” marriage to your own husband. So now they accuse you of adultery instead! They call you sinner because you love one man—and continue to love him after they term your love evil.

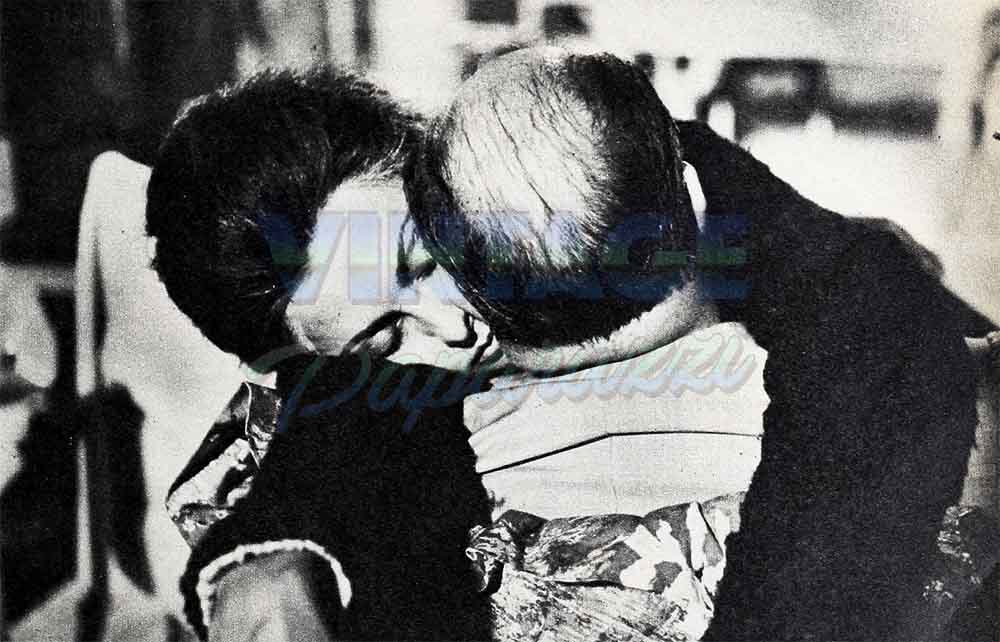

And what do they know of love, these people who so easily mouth mere words? Do they know how you died a little when you heard that he was seriously hurt in a plane? The jet on which he was flying from Paris to Rome flew into a vicious downdraft at 28,000 feet over the Alps. As it plummetted sickeningly before the pilot could regain control, Carlo was hurled against the seat in front of him, his right ear cut so badly that it took fourteen emergency stitches to close it. Do they know how you felt, rushing from Switzerland to Rome to be with him while forty-five plastic surgery stitches were then put into his ear? And did they consider it a sin, perhaps, that you knelt by his bed and wept when you heard that his first words, as he was taken, cut and bloodied, from the plane were, “Luckily Sophia wasn’t on board.” What do they know about loving a man?

A baby’s shrill cry sifted through to the waiting room. Even the card players froze for a second, and the readers put down their papers. Everybody in the room smiled.

No, this was not the time to be thinking of shame. One little flower forcing its head above the frozen earth can make you forget winter. One infant’s innocence can make you forgive the world’s cruelty.

The door opened again and a nurse walked swiftly to Sophia—and already Sophia felt in her heart that something was wrong. She followed the nurse out to the hail to hear, in a whisper, what was happening with Maria. The words penetrated in isolated snatches and phrases: “baby very tiny … in grave danger . . . doing everything we can to save . . . special equipment . . . round the clock care for the baby . . . yes, a little girl . . . mother is all right, doesn’t know of her baby’s problem—not yet . . . no, nothing you can do.”

Sophia went home and spent a sleepless night in prayer. In the days and nights that followed she begged God a million times to spare the life of Maria’s baby. An item in Louella Parsons’ column gave a stark account of what they all went through: “Doctors in Rome are fighting to save the life of the baby girl born prematurely to Sophia Loren’s sister Maria, married to Romano Mussolini, son of the late Italian dictator.”

A few days, and the miracles of happiness came to pass. The baby responded to treatment. thrived, and the doctors assured a harassed Sophia that her tiny niece would live and be well. . . . Maria asked her sister to be the baby’s godmother at the christening ceremonies. . . . Sophia’s picture was taken, holding her precious little Alessandria in her arms, cooing to her, loving her . . . and Sophia’s cup of blessings ran over.

A happy ending? We’re afraid not. With- in a few days, a new uproar commenced. In a Milan Catholic newspaper a leading moral theologian, the Right Reverend Giovanni-Battista, wrote an open letter addressed to Sophia’s spiritual advisor, Father Rotondi who had officiated at the christening. The prelate wrote that he could understand how “his old friend, Father Rotondi” would have wanted to help Miss Loren, but “I cannot understand how you could allow little Alessandria to be committed to the spiritual attention of the woman.

“I prefer to think that you were the victim of a fail into one of those snares from which we never seem to be officially safe,” the letter went on, “rather than to be convinced that you contributed, even in good faith, to an increase in the number of the world’s scandals.”

Three days later the Vicarist of Rome issued a communique invoking the Article of canon law which bans “persons who behave in a sinful way, publicly, gravely,” from standing as godmother or godfather at a christening. Although the communique did not mention Sophia by name, a Vatican press office statement did. It quickly pointed out that the communique “evidently referred to a baptism at which actress Sophia Loren was godmother.”

Joining in the chorus of condemnation, L’Osservatore Romano pointed out that so long as Italian and church law block Ponti’s divorce from his present wife and his marriage to Sophia, she is living in “public concubinage” in the eyes of the Roman Catholic church and is “therefore unfit for godmotherhood.”

Surprised at the fuss, Sophia remarked simply, “I wouldn’t have been there if I had known they didn’t want me.” But she also said, with a contented sigh, “It was one of the happiest events of my life. In any case, I am the child’s godmother and proud of it.”

The baby’s father, Romano Mussolini, came to his sister-in-law’s defense with a simple, warm-hearted bit of logic. He said, “She held the baby in her arms and loved it. What more do you want?”

—JAE LYLE

See Sophia Loren in Embassy’s “Madame”; in “The Condemned of Altona,” 20th, and “Five Miles to Midnight,” UA.

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE MAY 1963

AUDIO BOOK