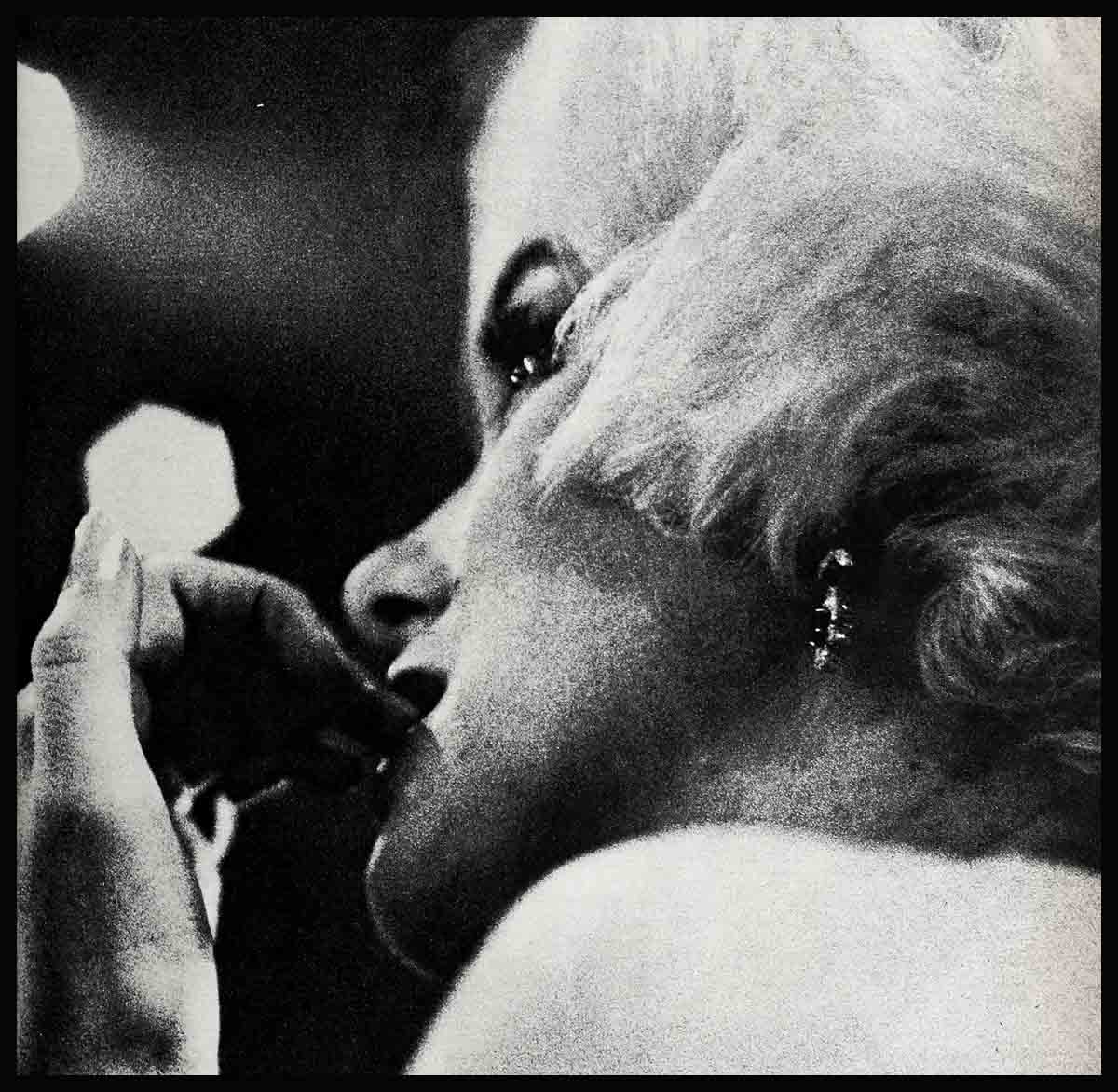

“Does it hurt to die?”—Marilyn Monroe

Everyone dies alone. Everyone thrashes alone in the darkness until even the thrashing stops and all there is is darkness. For each his own separate darkness. But she died alone as only crippled men in charity wards die, whose wives and friends and children are long scattered underground like sand in the wind. She was an ex-wife with three ex-husbands and three ex-stepchildren and an ex-studio that was suing her for half-a-million dollars. For a brief time she had belonged to each of them, but when she died she didn’t belong to anyone. There was no one to kiss her goodbye. There were no arms trying to push away the darkness for another five minutes, no tears as a last hot memory of love to carry with her into the frigid darkness.

“Does it hurt to die?” she had asked once. She was six years old and she had stopped to stare at a dog almost casually killed by a passing car. “Don’t ask stupid questions, Norma Jean,” said the woman who was taking care of her for the State of California that week or that month. “Leave the dirty thing alone, we don’t have all day.”

She died of a massive overdose of sleeping pills at 9 P.M. on August 4th, 1962. A Saturday night—the friendliest night of the week. She died behind a locked bedroom door while millions of teenage girls sat in their living rooms with boy friends, sharing chocolate cake and one of her old movies on television; while men played poker or read magazines; while wives got angry at husbands for the wrong lead against a vulnerable slam; while time was spent or killed or wasted and life trickled like colored glass through a million hands in a million ways.

She was found dead by her housekeeper at 3 A.M. with a telephone in her hand and an empty bottle of sleeping pills on the bedtable. And it was neither friend nor lover, but a doctor who wrapped her nude body in a blue blanket and carried it to the mortuary in the back seat of his station wagon. Next resting place—the morgue.

Does it hurt to die, Marilyn Monroe?

Sometimes it hurts more to live.

No one leaps into the dark unless the light is too painful. The dark is light enough only to those for whom sunlight is unbearable. Yet in a nation of sun worshippers, she was the sun, from her gold-dipped hair to her golden thighs kept honey-colored by an artificial lamp.

Sunlight glittered on her money, and she cupped fame in her hands like a golden apple. Boys watched her brassiereless body in a movie theater and panted in embarrassed, inescapable agony. She was sex without responsibility, and a hundred million men bruised her with their thoughts. Her moist lips, her singsong whisper, the incredible walk that was actually due to a lack of coordination, were the stuff that dreams are made of. And they proved—as she had always suspected—as insubstantial as dreams. Two months after Marilyn Monroe’s thirty-sixth birthday, they ceased to exist.

Why?

“I’m sorry,” said her first husband, Los Angeles policeman James Dougherty, sweating in his thick blue uniform on a summer Sunday. Her second husband, Joe DiMaggio, said nothing. He had never talked much, even to her. But he talked to her in death. He bent to kiss the beautiful dead face in her coffin and, weeping, whispered, “I love you, I love you, I love you.”

“It had to happen,” answered Arthur Miller, second most famous living American playwright and her third husband. “I don’t know when or how, but it was inevitable.”

The European newspapers blamed Hollywood.

“She is the victim of the glaring lights, the too severe demands, the cracking whips, the cheers and the juggling in the big circus tent of movies.”

“This woman was a product and a victim of Hollywood. . . . A human being of prefabricated fame made to live and yet frightened by the hullaballoo of publicity in the higher hells of manufactured film notoriety.”

Evangelist Billy Graham had an easy answer. “All that she searched for could have been found in Christ.”

The intellectuals had no answers, only premonitions. English poetess Edith Sitwell, clutching at a black shawl: “The poor girl. Somehow she seemed fated to be sad.” Photographer Cecil Beaton who thought her the most photogenic woman in the world: “I always felt that Marilyn was doomed to a sad end. She was a desperate creature, pitchforked into a world she knew nothing about.”

The inhabitants of that world—the other movie stars—offered only praise and platitudes. Gene Kelly was “deeply shocked.” To Peter Lawford she was “probably one of the most marvelous and warmest human beings I have ever met.” Jack Lemmon was “terribly fond of her.” The widow of Clark Gable said a prayer for her and Dean Martin was “sure it was an accident.”

And Gladys Baker Eley, Marilyn Monroe’s mother—her deteriorating mind locked behind the doors of one of the mental institutions in which she has spent the last twenty-eight years—could not even understand that her daughter was dead.

Why?

The simplest of human lives is too complicated to be pressed, like a dead flower, between the pages of a dictionary. And the supercharged soul imprisoned in its gilded 38-23-36-inch container was not simple. Marilyn Monroe was doomed from the beginning. She was born—a wingless bird—to an already mentally ill woman whose own parents had both died in mental institutions.

Illegitimate, and abandoned before she was two weeks old, she taught herself to fly. Born in darkness, she flew towards the sun. Using artificial wings of ambition and courage, she traveled in the orbit of the sun before her wings melted and she drifted—slowly, wingless and alone—into the final darkness.

A few weeks before she died she said, “I wasn’t used to being happy, so that wasn’t something I ever took for granted. . . . You see, I was brought up differently from the average American child, because the average child is brought up expecting to be happy—that’s it, successful, happy, and on time.”

She was twelve days old when she was bartered to a family of religious fanatics. Before she could walk, her sins were exorcised weekly by a razor strap. As soon as she could talk, she was forced to promise “never to drink, smoke or swear.” The penalty for disobedience was hell.

Happiness—road to hell!

She went to church three times each Sunday. The other days she scrubbed floors and scoured toilet bowls and prayed on demand. Each stain left in the toilet by chubby fingers was a sin eventually to be punished by eternal damnation. So was laughter. The only safety was pain. Pain would be rewarded by the eternal sunlight to come, while happiness was the road to hell. Sex—of course—was hell itself, and she was given her introduction to it at the age of six when she was raped by “a friend of the family.”

A year later she was transferred to a family of unemployed actors who rarely dressed further than their underwear. For toys they gave her empty whiskey bottles. For amusement they taught her to dance.

She had emerged—not into sunlight but into another kind of hell. Uncaged, she found herself in a limitless wilderness. A dozen times each day she prayed for them—and for herself.

When she was eight her mother had a second, final breakdown and was deposited efficiently in a state hospital like a penny in a coin bank. She would remain there until Norma Jean Baker became Marilyn Monroe and earned enough money to transfer her to a private sanatorium. To Norma Jean, her mother’s departure meant merely the disappearance of “that woman with the red hair.”

Norma Jean moved again—this time to an orphanage. Once more imprisoned, she began to stutter. In three years she grabbed only one hour of happiness. She was marched to a Christmas party for orphans at a movie studio and given a string of artificial pearls. From that moment on, she wanted to become an actress.

She was eleven when a good-hearted friend of her mother’s released her from the orphanage. But her new home was only another temporary one. Whenever her guardian was in a jam over money. Norma Jean was boarded out until the crisis was over.

She packed her only real possessions—the hair ribbons she had bought each month at the orphanage with her penny of spending money—and carried them with her to a dozen families in the next five years.

The string of artificial pearls was always around her neck, an artificial promise. “Some of my foster families used to send me to the movies to get me out of the house, and there I’d sit all day and way into the night—up in front, there with the screen so big, a little kid all alone, and I loved it. I loved anything that moved up there.

“When I was older, I used to go to Grauman’s Chinese Theater and try to fit my foot in the prints in the cement there. And I’d say, ‘Oh, oh, my foot’s too big. I guess that’s out.’ ”

Happiness was what she devoured on the screen: sleeping in a bed by herself on sheets that were changed each day; fresh orange juice for breakfast; Clark Gable kissing the back of her neck. She lived in a simple world of deprivation and despair. She imagined happiness to be just as simple.

And for a while it was. In one lush spurt of summer, her body ripened and boys crowded black as flies near the ripening fruit. At first she was bewildered when they offered her candy and rubbed their thighs against her plump buttocks in the corridors at school. Then she drowned in the warmth and amazement of being wanted—actually wanted—by anyone. She grew bold enough to demand from them—a ride on their bicycles, a glass of pop. occasionally even a banana split. But they always wanted more from her in return. Happiness was the road to hell. And sex—of course—was hell, and never in her life was she to be free from guilt.

When she was sixteen, her guardian—eager to untangle herself from responsibility—forced Norma Jean into marriage with James Dougherty, a twenty-one-year-old aircraft worker. Norma Jean agreed because “at least they can’t put married women into orphanages.” A few months later she made a rather pathetically inept attempt at suicide. When Dougherty joined the merchant marine, they both knew that the marriage was over, although they were not divorced until 1946.

She became a paint-sprayer in a war plant, then drifted into modeling. From that moment on, she was to earn her way through life with her body. She really never had any other choice except not to survive at all. Emotionally, spiritually, intellectually, she was a child deprived of even the simplest toys. Her body was her only gift.

Love was what she watched in the movies. God was the monster of her nightmares. A dozen sets of foster parents had kept her home from school whenever they had work that needed to be done. On her own she had managed one year of high school. But it was a frightening, embarrassed year. When she was forced to answer questions in class, she could only stutter. Her impoverished mind was too terrified to learn. Words were symbols that cut her mouth.

Years later, as a movie star, she was still to find herself unable to communicate with words, as desperately as she always tried. She would find herself unable to communicate in other ways, too. The language of the heart must be learned earlier even than the language of words. She had no chance to learn until it was already too many years too late.

No words—only a body

She communicated in the only way she knew how—with her body.

The years from 1946 to 1954 were almost happy ones. The inner nightmare quieted in her external struggle to fulfill the daydreams of her childhood.

In 1950—the unexpected result of a few minutes on celluloid as a cheap lawyer’s girl friend in “The Asphalt Jungle”—she became, herself, a daydream to others. The studio was deluged with letters demanding to know her name.

Almost psychopathically ambitious and touchingly wistful, she crawled—picture by picture—to the top of the world. “Don’t Bother To Knock.” “Monkey Business.” “Gentlemen Prefer Blondes.” “How to Marry a Millionaire.” “There’s No Business Like Show Business.”

By 1954 the world was hers. Even the revelation that she had once posed nude for a calendar only enhanced her ability to serve as a daydream. Men felt about her as she felt about herself. She was the physical part of love; the quick, violent sex in the dark. She thought of herself as worthless—except as a body.

As though understanding this, she picked for a husband the All-American hero of her adolescence: reticent, controlled baseball player Joe DiMaggio. To be married to DiMaggio proved her value, proved her right to tenderness and children. Perhaps she expected from this marriage the uncomplicated happiness that ended the movies she had seen as a child—where the poor-but-beautiful girl melted forever into the arms of the handsome-and-rich boy.

The marriage lasted only nine months.

Two years later she tried marriage once more. As DiMaggio had stood for the world of the body carried to perfection, so was sorrowful Arthur Miller the symbol of the world of the mind carried to perfection Their marriage lasted five years.

“The Seven Year Itch.” “Bus Stop.” “Some Like It Hot.”

Clean sheets. Fame. And champagne.

There was no longer anything to ask for. She had won. And so she began to choke on her own insecurities.

Three miscarriages proved that she was of no value as a woman. She tried desperately to become a great actress. Lee Strasberg felt she had the potential to be one of the great actresses of the stage. But she couldn’t believe him. She could believe only the dark whisperings in her own blood. Studying at the Actors Studio, entertaining Miller’s intellectual friends, only confirmed her worthlessness to herself.

She wanted to be free of her body, free of the guilt that it brought her—and she once tried to get rid of it with an overdose of sleeping pills. But she loved her body too—the soft, perfectly formed gift that had been the source of her only pleasure. She soothed it with lotions, caressed it with the most expensive of expensive towels, stared at it for hours in the mirror.

Once—when she was a child—she had been boarded with a family in a drought area. Each of the seven members of the family had bathed only once a week, and they had all used the same tub of water. It was always Marilyn who took the last bath. Now she spent hours in the bathtub, a thirty-three-year-old little girl escaping into a world she had never known.

If she had nothing else to hold on to. then her body must be perfect. She became hours late for appointments, spent the hours putting on her makeup six times. She dressed and redressed and then took her clothes off and dressed again. She once even missed a plane because she stopped in a ladies’ room to put on lipstick and stayed for an hour. The outside must be perfect because only then could she hide the darkness inside. The dark nothing.

And then the body failed

In the end. her body, too, failed her. “The Prince and the Showgirl” with Sir Laurence Olivier, “Let’s Make Love” with Yves Montand were financial catastrophes. “The Misfits,” a strange intellectual hybrid written by her husband, was only marginally successful, although her co-star was Clark Gable.

She tried psychiatry. But there are wounds too deep for psychiatrists to cure. She tried alcohol. She escaped into constant sleeping pills. She tried alcohol and sleeping pills together, gulping three or our pills with four or five glasses of wine. She tried stuffing her body with food and letting it go to fat.

As guilt and sin burrowed like worms, deeper and deeper into her intestines, she became more and more self-indulgent. She seduced herself with food and wine and sleep in an effort to obtain the unobtainable.

“She used to be called at 8 A.M. and arrive at noon,” said a bitter Billy Wilder who directed her in “Some Like It Hot” and swore never to work with her again. “Now she is called in October and arrives in May.”

Inextricably entangled in the darkness that had surrounded her since birth, she crept closer to immobility. She was always sick. Strange infections appeared and disappeared. Two dozen bottles of pills crowded her night-table. There were days when she couldn’t make the effort to leave the house at all. When she did—to go to the Foreign Press Association dinner last March where she received an award as “the world’s favorite star”—she staggered to the stage in almost a caricature of herself.

The string of artificial pearls was broken now. The artificial wings were melting in the heat of the sun. There was nothing left but darkness. Yet she tried one last time to free herself from the bottomless embrace of darkness and nothingness.

The last desperation

She lost twenty pounds, had her body massaged back into shape, agreed to make a new movie, “Something’s Got to Give.” If her body was all she had, then she would make the most of it. Once again she posed nude. The last time she did it, she had needed money for food. This time she needed proof that Marilyn Monroe still existed. And there was no proof. Nothing told her “Yes.”

She was a nude thirty-six-year-old woman. Attractive and desirable. But the magic was gone. The breasts were less firm, the buttocks more rounded. The gift was tarnished now, and she had nothing to take its place.

She found it almost impossible to face the cameras. In a month of shooting she was “too sick” to appear at the studio more than twelve times. The studio fired her.

And she was sick—incurably sick. She avoided mirrors now. She rarely took a bath. Her toenails remained uncut, her fingernails ragged. The road ahead was impassable. The road behind no longer existed. She could only wait—motionless, motionless, motionless.

In the end, she found herself able to commit one final act.

“It might be kind of a relief to be finished,” she had said less than two months before. “It’s sort of like I don’t know what kind of a yard dash you’re running, but then you’re at the finish line and you sort of sigh—you’ve made it! But you never have—you have to start all over again.”

But this time it was finished. Guilt and sin and beauty were commingled now. Hope was gone, but so was pain. If there was only darkness, it was a different darkness.

Perhaps a kinder darkness than she had ever known.

THE END

—BY ALJEAN MELTSIR

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE NOVEMBER 1962

zoritoler imol

2 Ağustos 2023Hello There. I found your blog using msn. This is an extremely well written article. I’ll be sure to bookmark it and come back to read more of your useful information. Thanks for the post. I’ll certainly comeback.