Tommy Sands: “Will She Die Because Of Me?”

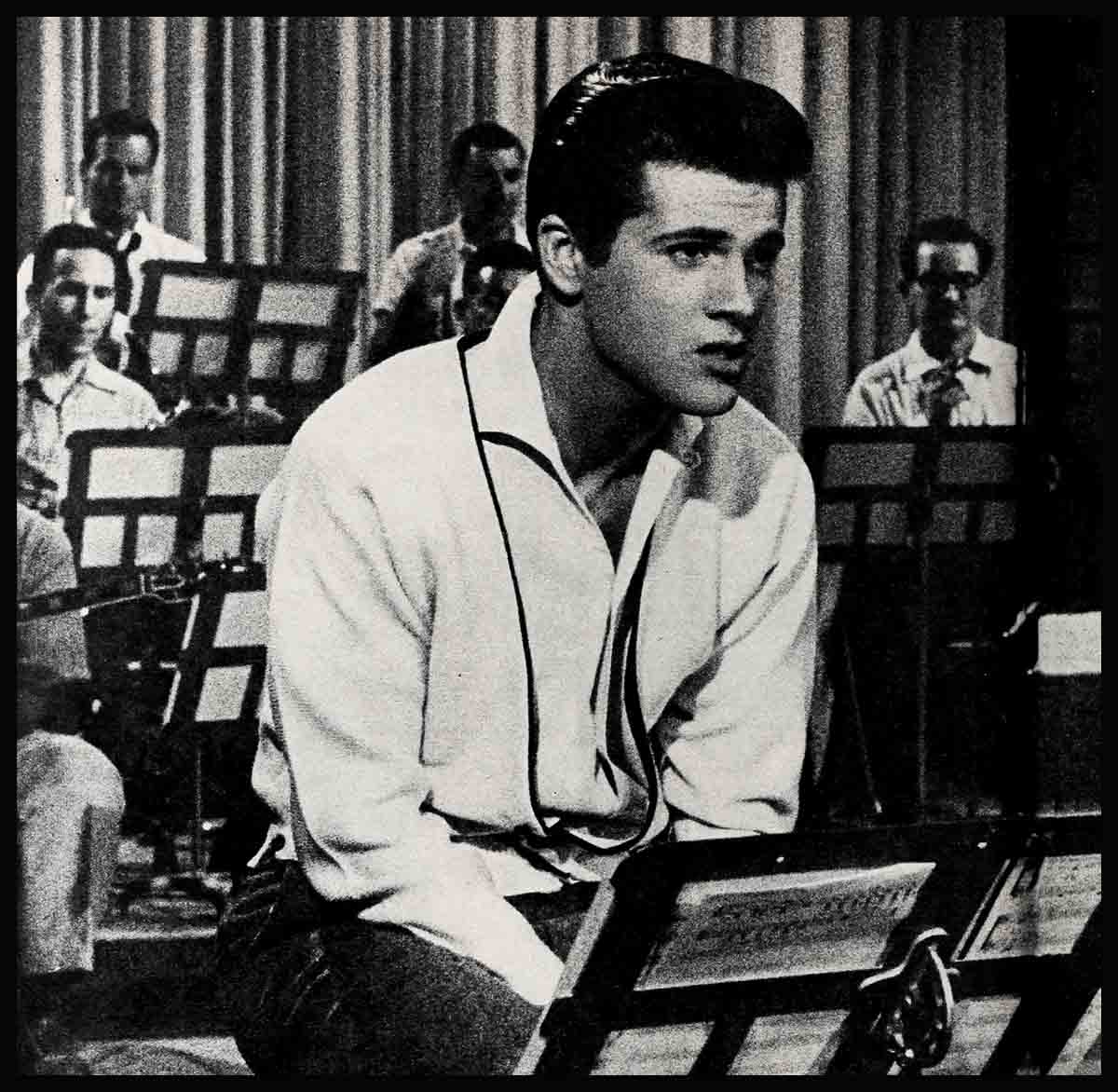

The notes on the pages spread out on the music stand before me were just a blur. I sat hunched up there on that stool looking out at the rows of empty seats, and straight through rehearsal all I could think of was her. Where was she, I kept thinking, why hadn’t she called me? I knew the police were doing everything they could, but I felt I ought to be out there, too, looking up and down every street in the city to find her. Even when everybody kept trying to tell me it wasn’t my fault, it didn’t help. I felt responsible. The conductor’s voice droned on with instructions to the musicians behind me, but all I could really hear was a terrible still voice inside of myself asking over and over again, “Will she die? Will she die because of me?”

I’d heard the news the minute I got off the plane. My manager, Ted Wicks, and I, had landed in Australia that warm Friday afternoon, and there was a great turnout of fans all shouting, “We want Tommy! We want Tommy! We want Tommy!” After flying through the calm skies of the Pacific and staring at miles and miles of peaceful blue ocean glittering in the sunlight, it was an exciting jolt to see and hear such a happy welcome.

No sooner did I step off the curved aluminum runway than a pretty brown-haired girl, just a little over five feet, wearing a pale-blue shirtwaist dress, came up to me and introduced herself. There was such a hubbub I didn’t hear her name.

“. . . I’m the vice-president of the Australian Fan Club for you,” she was saying.

“Is your president here?” I asked, smiling. I wanted to thank both of them, for this was a thrilling welcome—over three thousand fans. I spotted one group of over fifty of them. They were dressed in my favorite colors, red and white, and they had big red-and-white bows pinned on their dresses with the titles of all my songs printed on the long ribbon-ends in bright lipstick-red letters!

She didn’t answer me. make it?” I said.

“Oh, Tommy,” she broke down, her soft brown eyes staring into mine. “Bronwyn wanted to be here more than any of us, but . . .”

“Is something the matter?” I wanted to know.

But she just glanced away from me and, as we began walking through the hollering crowd, she said something I couldn’t hear.

“What?” I shouted above the clamor.

“Bronwyn . . .” she continued, and tears streamed down her pink cheeks, “. . . Bronwyn’s lost!”

“What?” I said, not fully believing what I’d heard.

“She’s lost . . .” she said, stifling a sob. “She’s been lost for two days.”

“But . . . how can a grown-up girl get lost?” I wanted to know. Maybe this was a joke or a trick they were playing.

“Oh, Tommy,” she said sadly. “If only you knew . . .”

The crowd roared like a lion, and everyone stomped his feet to the beat of “We want Tommy! We want Tommy!” I waved to them all, then asked her if she would mind waiting for me until I’d gone through customs. I just couldn’t understand what she meant. How could a teenaged girl get lost in her own home town? But as I looked into my companion’s sad brown eyes, I knew this wasn’t a prank. She was telling me the truth, and I wanted to know what had happened.

After customs, she explained everything. Bronwyn King, the president, was terribly excited about my arrival. She was the one who’d organized the sensational turnout. But her dad, when he heard Bronwyn was coming out to the airport to lead the welcome-to-Australia gang, refused to give her permission. He told her he’d heard about all the awful things fans did to their idols. He’d read about singer Johnnie Ray’s visit to Australia, when the fans pulled his hair and ripped his clothes and just about suffocated him. And he didn’t want his daughter to be a part of a wild rock ’n’ roll riot.

Bronwyn tried to tell him it wasn’t usually like that, but her dad wouldn’t listen. He told her she wasn’t allowed to visit the airport, and he was adamant about his decision. “Anyone who sings rock ’n’ roll,” he said, “simply couldn’t be a gentleman, and I don’t want my daughter associating with that sort of people.”

Bronwyn called the vice-president in tears and asked her to lead the welcoming party.

Then, two days before I arrived, Bronwyn was reported missing from home. Her parents summoned the Sydney police to look for her. Friends, relatives, acquaintances were called. No one knew where she was. For two days the police had been trying to track down information on Bronwyn; they even wired New Zealand, where she had distant relatives.

“Doesn’t anyone have any idea where Bronwyn is?” I asked the vice-president, after she told me the upsetting story.

Fidgeting with the long sleeve of her blue shirtwaist dress, she said, “I . . . I don’t know. But you’re going on to Melbourne tomorrow, aren’t you? Maybe . . .” She paused, “If nothing’s happened to her, maybe she’s waiting for you there, waiting to say hello!”

Suddenly I felt cold. Goosebumps appeared on my arms. Supposing something had happened to Bronwyn, supposing she was lost in some out-of-the-way area, supposing she didn’t have any food, supposing she was hurt . . . I choked on my thoughts. All on account of me, her life was in danger!

Scary images throbbed in my head. I looked into the vice-president’s red rimmed eyes, took her hand and tried to comfort her.

“I’m going to make a plea,” I said, my voice fuzzy from fear. “Right now!” And we all drove to the main section of Sydney, with its friendly inns and modern drug stores, old-fashioned dry goods shops and slick beauty parlors, and I asked permission from the city officials to set up a microphone on top of a roof to speak to the townspeople. If anyone knew anything of Bronwyn’s whereabouts, I wanted him to come and tell us . . . and I’d go to her personally, wherever she was.

But nobody knew a thing. That after- noon and evening we waited hopefully for some word, but all everyone kept saying was “Poor Bronwyn!” or “Gee, maybe she’s all right” or “I hope nothing’s happened to her!”

And that night, when I was on stage singing, I kept hoping Bronwyn might be out there, hidden in the audience, listening. Maybe she’d come backstage and tell me she was all right. But, still, a shuddering fear rifled my heart. “Supposing she isn’t here,” I told myself. “Supposing she’s lost somewhere and it’s dark and she doesn’t know where she is. Supposing she’s hurt and needs help!” I kept praying to God to look after her, to keep His eye on her, to protect her. Because, deep down somewhere in the cave of my heart was the awful, awful thought, the scariest one—“Supposing Bronwyn is dead . . .!”

As I packed to leave for Melbourne the next morning after the show, I kept wishing the telephone in my hotel room would ring, that someone would tell me Bronwyn was found and that she was all right. But the phone never rang.

I tossed all night long.

The next morning, I was up at dawn to call the police station.

“Have you had any word from Bronwyn?” I asked.

There was a long pause from the desk sergeant before he answered, “No, Tommy. I’m sorry. Not a word!”

Melbourne’s a couple of hundred miles from Sydney, and it took about an hour for Ted and me to fly there in a shiny grey, four-engine airplane. When I got off the plane, one of the disc jockeys for the top rock ’n’ roll radio program in Melbourne greeted me and told me all the fans in Melbourne were worried about Bronwyn. The newspapers were carrying stories about her. Bronwyn’s mother, Mrs. King, had flown in yesterday to check with Melbourne relatives.

I asked to meet Mrs. King. We drove to the large Chevron Hotel where Ted and I had reservations, and Bronwyn’s mother came to see us.

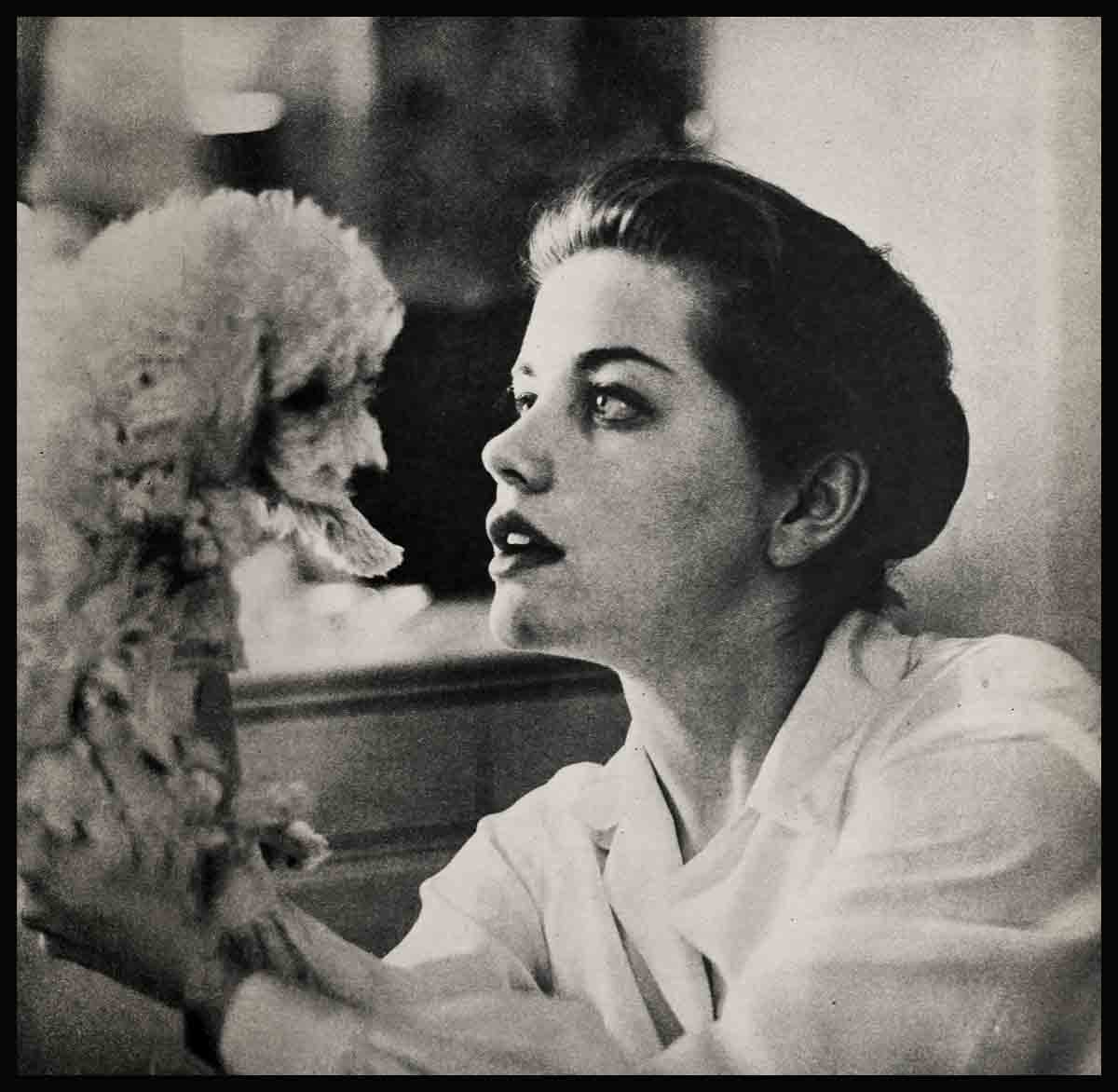

She was a young-looking woman—slender, tall, brown-haired. Her dark eyes looked kind; and although she appeared calm I knew she must be nervous be- cause she was at a loss for words.

“I just can’t understand it,” she said in a soft voice. “Bronwyn’s such a good girl. Why, she’s one of the honor students in her class.”

“Why don’t I make another appeal?” I suggested. “On the rock ’n’ roll program this afternoon.” I’d been scheduled for an interview with the disc jockey who’d been playing more and more of my songs (because of Bronwyn’s strong fan-club campaign in my behalf). Everyone, by the way, told me how influential Bronwyn’s club had become with the disc jockeys.

Shaking her head, Mrs. King said something under her breath.

“I’m sorry,” I said. “I didn’t hear you.”

“I wish,” she said, “my husband had met you. I think he’d change his mind about all you rock ’n’ roll singers if he did!”

I felt a little funny for a minute. Then we left for the radio station where I was to make my appeal.

“Hi,” I said over the table mike. I sat next to the red-haired disc jockey who had met me at the airport. “This is Tommy Sands. I want to say hello to Bronwyn King, the president of my fan club here in Australia. If you’re out there, Bronwyn, listening to me, I want to meet you, and I hope you’ll call me up after the broadcast. I’m at the Hotel Chevron. Just ask the telephone operator to connect you with my room.”

“Bronwyn,” I continued, “we’re all anxious about you. Please get in touch with us. We’re all praying that you’re well!”

I returned to stare out the big bay- window in my hotel room. Newspaper reporters and photographers kept coming into the room, asking me if I’d had any news from Bronwyn after my appeal.

I told them we were waiting.

One of the reporters asked me how I’d feel if Bronwyn were never heard from again, and I just couldn’t answer him.

I paced my room at least a hundred times, and waited for Bronwyn’s call, but the telephone didn’t ring. I stared at the hard black instrument over and over again. You just don’t realize how important the ring of a telephone can be until you’re desperate for news or information.

I paced my room again. “It’s all because of me,” I thought, my hands sunk deep in my pockets, “all because of me.” Ted, my manager, tried to get me to take a nap, but I couldn’t. I was too jumpy to think of sleeping.

For a moment I thought I was imagining it. But one of the reporters in the room said, “Hey, didn’t that sound like a knock?”

The reporter and the photographer and Ted and I listened. There it was again. A feeble knock-knock-knock. Timid. Like a frightened child’s knocking.

I looked into Ted’s eyes, then I ran to the doorway.

I unhooked the latch, opened the door, and there, in front of me, stood two teenaged girls. One of them was bawling, tears rolling down her rosy cheeks. She was tall and pretty with dark blond hair fluffed softly around her heart-shaped face. I could barely see her warm brown eyes for the tears.

Her girlfriend was shorter. She had long black hair and a dimple.

“Are . . . are you Bronwyn?” I heard my voice asking. My heart skipped a beat.

She didn’t answer. She couldn’t speak through her tears. But she nodded her head to say yes, and I took her in my arms and hugged her. “Thank God,” I said, “thank God.”

The photographer started to snap pictures with his flash camera, but I asked him for the film. I didn’t want any of these pictures published. Bronwyn had come back . . . that was what was important, and I didn’t think it was fair for the photographer to take pictures of her in tears.

I asked her if I could call her mother, who was waiting anxiously for news of her at her aunt’s in Melbourne, and Bronwyn nodded yes. Ted offered to call Mrs. King, and I ordered hot tea and toast for Bronwyn, and her girlfriend.

“Oh, Tommy,” she cried, her eyes brim- ming with tears. “I never, never thought I’d meet you.” She swallowed hard, then sat down in a chintz-covered armchair and she sobbed loudly. “But what have I done, Tommy? I . . . I ran away, and I’ve made my parents look so awful in front of everybody.” She sobbed so loudly it was hard to understand everything she was saying.

“This is my girlfriend,” she said. “I’ve . . . I’ve been staying with her. I didn’t tell her folks I’d run away. I . . . I just told them I came for a visit.”

Ted was on the telephone now talking to Bronwyn’s mother.

“Bronwyn,” I said, “would you mind if we asked your mother to come over? She’s so worried, and she wants to see you.”

“I don’t mind,” Bronwyn sobbed, dabbing her eyes with a wrinkled ball of a handkerchief. “I . . . I miss her so much. But she’ll never forgive me! And my father . . .” Bronwyn never finished the sentence.

“She’s afraid her father will hate her,” her girlfriend explained.

“No, he won’t,” I said quickly. “He probably feels just like all of us. We’re so glad to know you’re alive and well!”

“But he’ll hate me for running away,” Bronwyn cried.

“He’ll forgive you,” I said.

“He won’t,” she told me through her tears. “You just wait and see!”

Mrs. King arrived, and both Bronwyn and her mother cried as they embraced each other. “Oh, Mom,” Bronwyn sobbed. “I’m sorry, but I . . . I just couldn’t help it. I couldn’t stand Dad saying all those—things about Tommy and rock ’n’ roll.”

“Bronwyn,” her mother said quietly, “don’t let’s talk about that now. What matters is that you’re safe.”

“Mom,” Bronwyn said, her dark eyes glimmering from crying, “what’s Dad going to say?”

Her mother patted Bronwyn’s arm. “Don’t worry about that now.”

I interrupted—I couldn’t help myself. “Mrs. King,” I said, “when I get back to Sydney next week, can I sit down and talk to Mr. King?”

“Oh, Tommy,” she said softly. “I don’t know if that’ll do any good. Mr. King’s a man with a strong mind and will.”

And suddenly Bronwyn started to cry all over again.

The first thing I did when we got to Sydney that next week was to pick up the telephone. Mrs. King was at home. “Last night,” I told her, “I had an idea. I was wondering if you and Mr. King and Bronwyn would be my guests tonight at the Sydney Stadium where I’m singing.”

“Tommy, that’s so thoughtful of you,” Mrs. King said. “But I’m afraid you don’t know my husband. I doubt if he’ll want to come.”

“But will you tell him I called and extended a personal invitation? And if he likes the show, I hope he’ll come backstage afterward for a visit.”

She promised she’d ask him, crossed my fingers for good luck.

That night, dressed in my white dinner jacket and midnight-blue pants I waited in my dressing room at the Sydney Stadium for news from Ted about Bronwyn and her folks. Had they come . . . or hadn’t they come? I wanted to know.

Ted finally came backstage and told me they hadn’t arrived. The tickets were in their name in the ticket cage, and the ushers would show them their seats if they arrived late. But the show couldn’t be held up any longer. The crowd had arrived, and it was time to start.

Sydney Stadium’s a huge arena, bigger than Madison Square Garden, and when I went out there to sing in the bright blue-white pool of light while The Sharks accompanied me (Hal on drums, Scotty on electric guitar, Leon on bass fiddle and Eddie on rhythm guitar), I couldn’t help thinking . . . “I’ll never know if they’re out there, so I’ll just pretend they’ve come, and I’ll sing all these songs for Mr. King.”

I sang “Sing Boy Sing” and “Teenage Crush” and “Going Steady” and “Unchained Melody”—all the songs from my albums. I also sang a special song Id written for my Australian fans called “Sydney Blues.” I wrote it in Hawaii before we left for Australia, and I didn’t realize what an eerie, fateful meaning the lyrics had until I sang them in front of that hushed ‘audience. . . .

“There’s an old back road leading down our way;

Yes, there’s an old back road leading down our way—

Where you can find and lose a woman

All in one day. . . .”

Everyone in the audience loved the blues beat, and the applause was wonderful. After the show I went backstage. I was moody and blue. I’d hoped Bronwyn and her mom and dad would come. I’d wanted them to see the show. I guess, deep in my heart, I’d wanted Bronwyn’s dad to know what rock ’n’ roll really is.

All smiles, Ted burst into the dressing room. “Tommy, Tommy,” he said. “the show was great! And they’re here! Bronwyn and her folks, and they’re coming backstage to meet you!”

“You kidding?” I couldn’t believe it.

But there they were—Bronwyn in a lovely sky-blue dress, her mother in a smart lilac-colored silk suit and her dad—a nice-looking man of medium build with grey hair at the temples. He seemed very quiet, and I noticed he wore a hear- ing aid behind his ear.

“Gee,” I said, my voice a little too loud from the sudden surprise of it all, “I’m so glad you came.”

I shook hands with them all.

“Tommy,” Bronwyn’s dad said in a low voice. “I . . . I guess I have an apology to make. I just didn’t have any idea that you rock ’n’ roll fellows were decent young men. But this show . . . why, it was wonderful!”

Bronwyn beamed.

“Rock ’n’ roll,” he continued, “isn’t so bad, after all. I just didn’t know any better.”

There was a tight lump in my throat. I didn’t know what to say. Finally, Mrs. King spoke out. “I hope you’re going to let Bronwyn see Tommy off at the airport when he leaves for the United States.”

Mr. King grinned. “Why not?” he said. “And if she needs a lift, I’ll drive her out there myself.”

Suddenly I was speechless. I tried to smile, but that lump in my throat wouldn’t budge.

“Gee, thanks, Mr. King,” I said.

We talked for a while longer, and as they said goodbye the lump in my throat kept getting bigger and bigger. Like a fool, right out of the blue, I started to cry. I don’t know why. But I did. I was so happy, I guess, knowing everything had turned out all right.

THE END

DIG TOMMY SANDS ON THE CAPITOL LABEL.

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE AUGUST 1959

gralion torile

21 Haziran 2023Very interesting information!Perfect just what I was searching for! “…obstacles do not exist to be surrendered to, but only to be broken.” by Adolf Hitler.