Detour To Destiny—John Kerr

Every afternoon, along the streets of Beverly Hills, nursemaids promenade with their charges, most of whom are the offspring of famous parents or grandparents.

On one recent afternoon, a pretty young mother set out on an airing with her twenty-month-old twin daughters. The first nursemaid she met eyed the girls, exceptionally pretty chicks with bright blue eyes and copper-red hair, and asked, “Whose children are those?”

“Mine,” said the young mother, trying not to sound too proud.

“This,” said the nursemaid, nodding toward her handsome charge, “is the son of Rosemary Clooney and Jose Ferrer. And,” said she. looking down the sidewalk, “here come the James Stewart twins.

At this point a sightseeing bus drew to a stop. Obviously, the driver knew most of the nursemaids by sight. He said into his microphone, “On the right is the Rosemary Clooney-Joe Ferrer baby, and next to him are the Stewart twins, Judy and Kelly.” Then he thrust a head out the window. “Who are the little redheads?” he wanted to know.

The friendly maid asked the redheads’ mother, “Who’s their daddy?”

“John Kerr,” said Mrs. Kerr in vocal headlines.

The maid shrugged and wafted a regretful gesture toward the bus driver. “Nobody anyone knows,” she said.

This ranks as one of the greatest errors made by an innocent bystander.

To anyone who knows Broadway, the name John Kerr conveys a special magic, because of his work in “Bernardine” in 1952, in “Tea and Sympathy” in 1953, and in “All Summer Long” in 1954. To anyone who knows Hollywood, the name John Kerr in the cast of “The Cobweb” and “Gaby” (his latest starring vehicle opposite Leslie Caron) proves that a sensitive and an eloquent new talent has been added to the motion-picture scene.

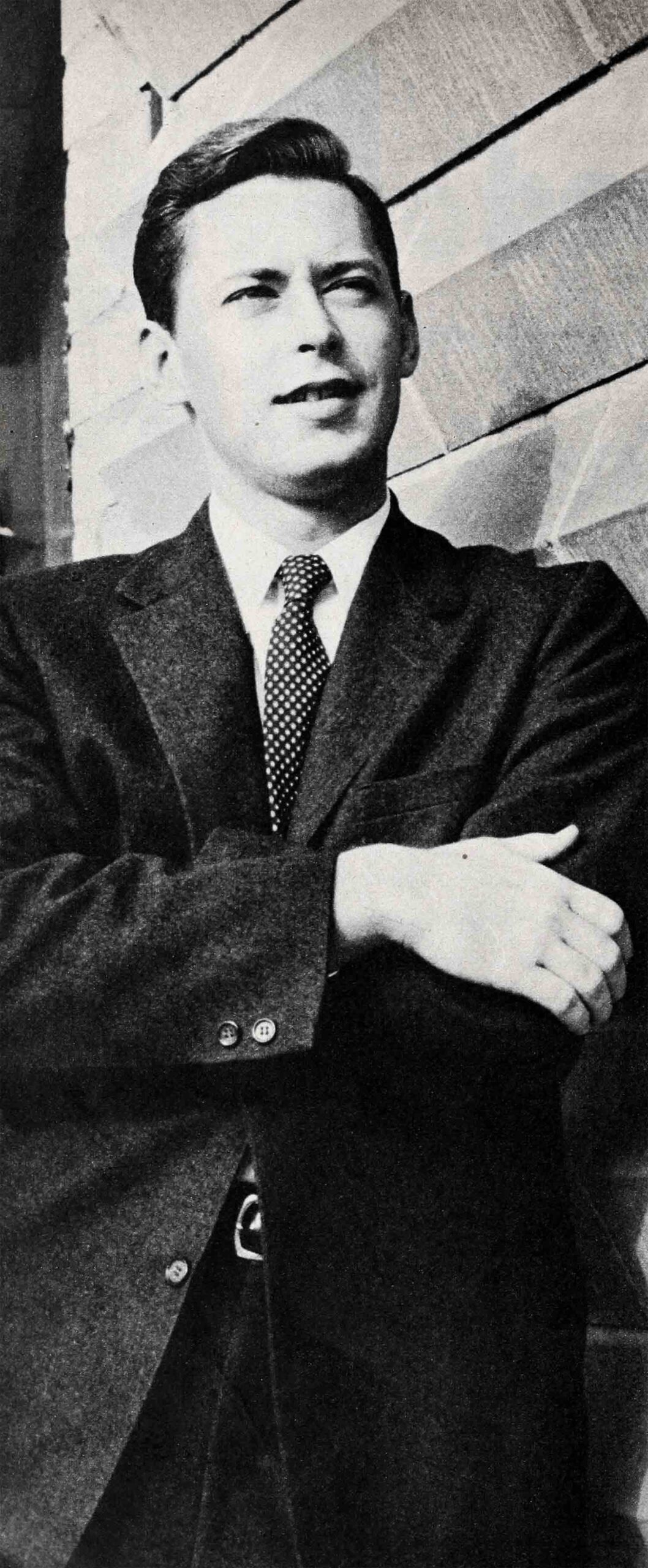

What is he like, this John Kerr whose name will probably become as famous as that of Tony Curtis or Rock Hudson?

His name is pronounced “car,” and his appearance is deceptive. A tall (six feet), slender (165 pounds) type, John reminds one of the Boston police cars which patrol about in almost pompous fashion—but which are capable of doing over a hundred miles per hour under pressure.

Born in New York City, John was educated at Phillips Exeter and at Harvard, graduating in 1952 with a Bachelor of Arts degree. Currently—in addition to everything else he’s doing—John is preparing the thesis required for a Master of Arts degree. The subject? Russian literature!

Upon first meeting John Kerr, the uninitiated observer might be pardoned for thinking he is the typical Ivy League product—dignified, intellectual, modest, and extremely sensitive. But those who know John well feel that it would be a shame to stop there, because he possesses an ad- venturous enthusiasm and a “wicked” sense of humor.

A fine example of his come-what-may enthusiasm was shown on John’s student-tour of the U. S. In 1950 he bought “at a bargain” a 1949 popular-make, one-owner, in-perfect-condition convertible. It didn’t occur to John to examine the canvas top before tendering a check in full payment.

The deal consummated, John and a classmate set out for San Francisco mainly because John’s actress-mother, the noted June Walker, was appearing in a play in the Bay city.

Everything went fine until noon of the first day when a steady drizzle set in. Up came the top with the scream of tearing canvas. “Looks a little like I’ve always imagined the Grand Canyon must,” said John, “but I think we can fix it.”

Stopping at the first drugstore, he bought a large wheel of adhesive tape and a bottle of clear nail polish. John might have been a surgeon, closing a gaping wound, judging from the care with which he brought the torn edges of the canvas together and applied the tape. That done, he painted the tape with nail polish in order to make the mend as inconspicuous and as waterproof as possible.

Late that afternoon, the rain stopped and the wind rose, clawing at the tender top. Another rip developed and was soon patched with infinite care. Thirty miles farther on, a new fissure opened, and a hundred miles beyond that, another slit occurred, letting in the weather.

“By the time we reached San Francisco, eight days later,” John recalls, “I had a new top constructed entirely of adhesive tape and nail polish. On that trip, I spent more on tape and polish than I did on gasoline, and I’m not kidding.”

For a brief and wonderful few hours in Nevada, John thought he had hit upon a scheme that would make it financially possible for him to junk his tape top and purchase a new superstructure. He stepped up to a slot machine in Elko, dropped a quarter in the slot, pulled down the handle, and out flushed a flood of silver. Eight dollars, to be exact.

“Why hasn’t someone told me about this?” John wanted to know.

His traveling companion, who had been having unpleasant experience with a dime machine, said nothing.

They drove on to Reno, and John strolled up to the nearest dollar machine. His expression was executive, and his hand on the lever was steady. Imagine finding a little old money tree—outside of Texas.

Thirteen dollars later, John said to his friend, “I see what you mean,” and on the fast highway leading to San Francisco, he added, “Thirteen bucks would buy a lot of adhesive tape.” At that moment he gave up gambling forever.

As John remembers it, “The trip back to Boston was made in only six days and about twenty-two miles of tape. My mending technique had improved.”

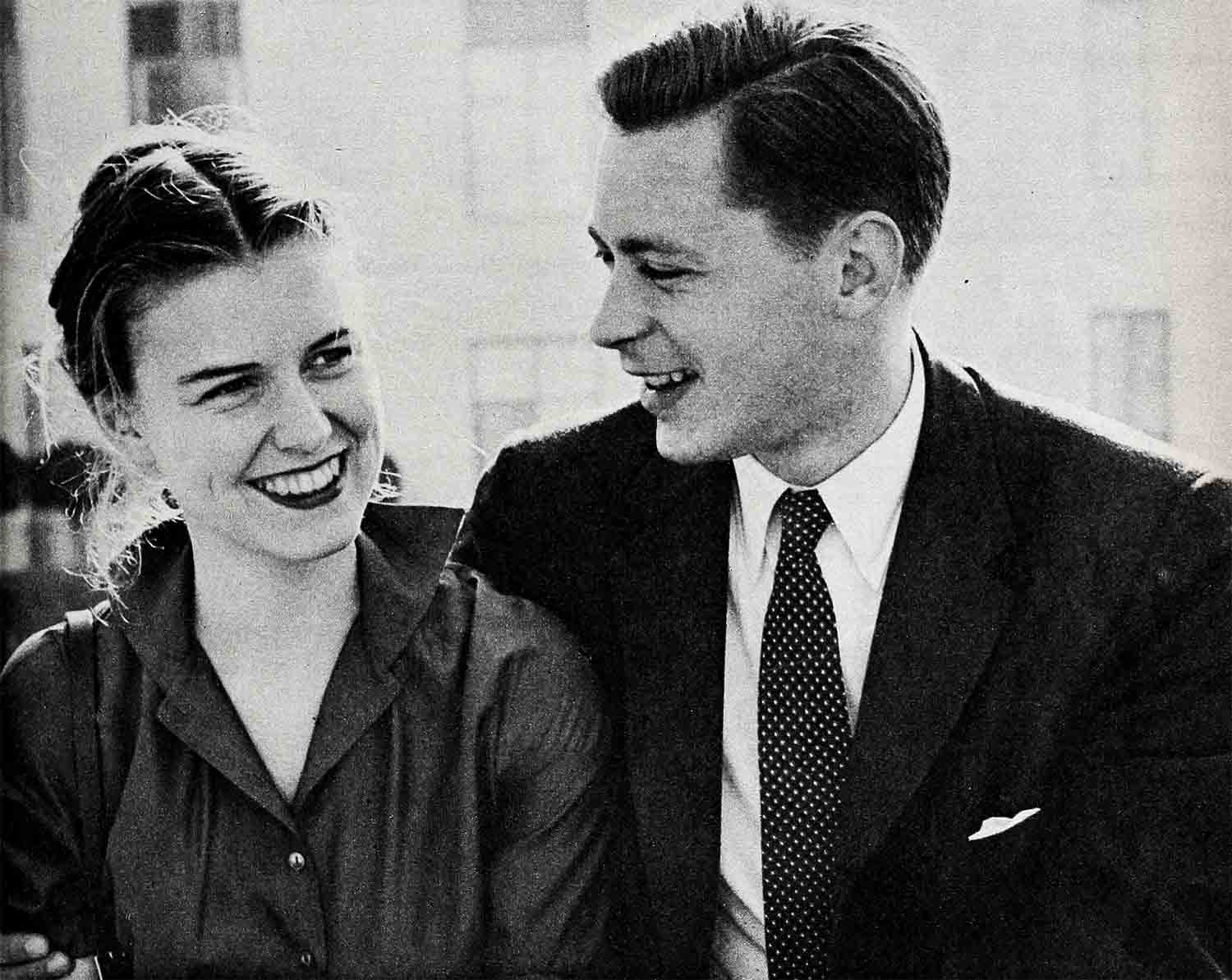

Equally confusing and unpredictable as his cross-country trip was John’s romance with Priscilla Smith. They met when he was a senior at Harvard and she was a student at Radcliffe, and the “adhesive tape” in this case was Serbo-Croatian. They were in class together.

That’s right: Serbo-Croatian.

Upon learning this, a new acquaintance once asked John, “How on earth did you happen to register for Serbo-Croatian?”

“I was looking for a course in which I felt I could knock out an A,” said John in the tone of a man who feels he has just been asked an idiotic question.

To anyone who has ever struggled through first-year Latin, John’s considering Serbo-Croatian as a pipe course, a cinch for an A, is probably unbelievable. He belongs in the isolation booth for the $64,000 question, not in a college classroom exchanging long and meaningful glances with a devastating co-ed.

During the filming of “Gaby,” a member of the M-G-M Publicity Department asked John which of Miss Smith’s charms first diverted his attention from Serbo-Croatian. John mulled over the query, finally murmured, “You haven’t met my wife, have you? No, you couldn’t have, or it wouldn’t be necessary for you to ask that question.”

Silence hung like a storm over the scene for a moment before John burst into a sunny smile to explain, “There’s too much about Priscilla that is remarkable for me to specify any one attribute.”

In any case, Remarkable Priscilla and Admiring John were soon leaving the classroom together, discussing problems of Serbo-Croatian translation. John found the course as easy as he had hoped. After all, he had studied Russian and French, and had always had an “ear” for languages. (Leslie Caron says his French accent is as near “native” as a foreign-born person usually manages. John had no trouble exchanging chit-chat with her.)

To go back into John’s history a bit: Although he was preparing himself at Harvard to teach English (well fortified by other languages), he had spent most of his summers doing theatre work.

At ten, he made his acting debut as Ruth Chatterton’s son in a performance of “Tomorrow and Tomorrow” at the Cape Playhouse. During ensuing summers he became a junior fixture at the Playhouse, absorbing technique, timing, and the knack of making a line pay off or dropping it flat. His unofficial tutors were the best. One of them was the late Gertrude Lawrence, with whom John appeared in “O Mistress Mine,” and “September Tide.”

When John entered Harvard, he turned his attention to the Brattle Theatre in Cambridge, and spent his vacations tampering with the drama in various capacities. Eventually, it was his appearance in the Brattle production of “Billy Budd,” the Herman Melville classic, that led to his debut on Broadway in “Bernardine.”

Meanwhile, it was only logical for John to take Priscilla Smith to a Brattle Theatre production on their first formal date. John still thinks they might have performed a more appropriate play than “King Lear” for the occasion, but he also recalls that it served as familiar background for an unfamiliar mood. Like falling in love during the season’s wildest football game, played by a pair of powerful teams—neither of which is from yourcollege. No matter how much excitement there is on he field, it can’t compare with your personal elation as you sit in the stands, close to your exquisite neighbor.

By Christmastime, John knew he wanted to marry Pricilla as soon as possible. To express this sentiment, he wanted to give her a Christmas memento that would be significant—short of an engagement ring—but not financially embarrassing.

Every girl in the world who has ever yearned for a sweetheart both sentimental and practical, will applaud John’s choice. From the plush Georg Jensen shop in New York he selected a Danish silver brooch fashioned into a timeless love knot.

Priscilla proved to be equally resourceful. She had ordered, from Russia, a copy of Tolstoy’s The Cossacks,knowing how much John wanted to read the work in its original language.

Priscilla’s family noted the implications of these gifts, and decided to voice their feelings. They pointed out that John was barely twenty-one, Priscilla not even that grown-up. They mentioned the cost of food, clothing, housing, and transportation —plus the financial frenzy caused by the visits from that persistent caller, the stork.

Because there wasn’t much else they could do, John and Priscilla decided to wait at least until after graduation. They had, they explained somewhat loftily, a number of things they wanted to discuss and settle between themselves before they married. This is a technique known as putting elders in their places when there doesn’t seem to be an immediate place in the world for youngsters in love.

John and Priscilla’s discussions were carried on several evenings per week until three, four, and five o’clock in the morning, both in defiance of college rules and the danger of catching pneumonia.

Much of their conversation doesn’t concern us, since it consisted of the usual expressions of wonder that, in this wide, wide world they had somehow met. However, some of it reveals so much about John, it needs to be mentioned.

For one thing, John outlined to Priscilla his dream of a home and explained the reasons for his dream.

The child of theatrical parents, John knew hotels and hotel rooms intimately. As far back as he could remember, he had known how—when alone—to order a sensible breakfast, lunch, or dinner in a hotel dining room. While other youngsters his age were struggling with fractions, he was able to glance at a dining room check and correctly compute a proper tip.

Many of his Christmas holidays were spent in a hotel room around a small tree which had been sent upstairs by the hotel florist. Often it was decorated by John and one of the maids, because John’s mother had to sandwich her holiday shopping between matinee and evening performances and had neither time nor energy enough to do more, much as she yearned to make much of the season for her son.

While other children were learning carols and hymns, John came to understand that at Christmas there are always the lonely and the wretched who must turn to the theatre for holiday cheer. His mother was one of those who spread cheer, for her performances gave a hungry-hearted audience an evening of goodwill.

To understand is one thing, to accept is quite another.

“I made up my mind right then,” John told Priscilla, “that one day I was going to have a home of my own. A house with a huge kitchen in which there was a fireplace and a big round table surrounded by captain’s chairs.”

Friends would gather there for all the sentimental holidays, John continued, and eventually there would be a collection of children to fill the cozy room with lots of laughter and happy conversation.

The kitchen would be used like all kitchens, but it would also be dining room, den, family room, library, and playroom. And near this central meeting place would be the bedrooms, to be used for sleep and discipline. It was John’s idea that the only punishment likely to be needed to keep a large family in bounds would be banishment from the group.

Of course, he agreed with Priscilla, it would be many years before they could have a family, but it was good to have a plan for the future. He must get a job, and Priscilla intended to do the same. Then, perhaps, in a year they could be married . . . at least within two years.

As it worked out, John won a part in the Broadway production of “Bernardine” shortly after he had worn cap and gown in the Harvard commencement march, so he and Pat were married on December 28, 1952. They set up housekeeping in a New York apartment and were going the familiar routine of painting, papering, and searching for the “good” little chair at a reasonable price, when two things happened. John was voted 1952’s most promising newcomer by the New York drama critics—and “Bernardine” folded.

For several weeks, John’s dream of oak-strewn acres surrounding a rambling, hospitable house seemed like smoke out of a long-stemmed Oriental pipe.

However, destiny’s child had been noticed too enthusiastically in “Bernardine” to suffer a permanent case of the doldrums. In the late summer, he went into rehearsal opposite Deborah Kerr (no kin) in “Tea and Sympathy,” and opening night was made memorable by the realization that the play was to be a smash hit—and by the news that John was to become a father the following May.

As it turned out, he became two fathers in May. That is, he became the male parent of red-haired twin girls, christened Jocelyn and Rebecca, known locally as Jossie or Little Oslyn, and Becky or Backy Becky. (You know how parents are.)

One of John’s first tasks, after the girls arrived, was to go shopping for a second layette—particularly infant shirts. When he explained what he wanted to the saleswoman, a grandmotherly type, she unfolded the proper size on the counter with the observation, “And there you have it.”

John studied the shirt for several minutes. He had the awful feeling that anything small enough to fit into that garment couldn’t be real. In a sepulchral voice he said, “It looks terribly tiny.”

The saleswoman wanted to know how much John weighed when he was born. He said he thought about seven pounds.

“This is the size you wore,” said the lady, “and look at you now.”

John still isn’t sure why he found this comforting, but he did.

If you’ve been worrying about the wicked sense of humor mentioned earlier as a Kerr attribute, settle down. We’re getting to that. When John was asked by a Chamber of Commerce type what there was about Hollywood hat surprised him, he said dourly, “The place is misrepresented,” and went on to explain that any well-read person must believe that movies are made in the midst of frenzy, for two or three hours per day. The rest of Hollywood’s waking hours, the country has been led to believe, is taken up by trips to Palm Springs, trips to Las Vegas, long lazy hours around one’s own swimming pool, and long, hectic nights around a table at Ciro’s, The Mocambo, or Romanoff’s.

“What yor expect is a sort of lotus-eater’s paradise with symphonic sound effects,” John added. “What you get is Detroit with palms.” Hollywood proved to be the hardest-working community John had ever known. Instead of maintaining a high level of energy and dynamism for the three hours required by a stage production, the astonished actor discovered that he had to sustain a mood, a characterization, and lots of energy over a period of eight to ten hours daily. “The first month nearly killed me,” he recalls.

After the first month, however, John must have tapped fresh reserves of vitality, because he and Priscilla were much in demand socially. One reason may have been John’s uncanny ability to impersonate his fellow players. His imitation of Lauren Bacall (including deep-well voice, down-under look, and tilted-pelvis gait) was perfected while John sat quietly—wearing an innocent expression—on the set where “The Cobweb” was shot.

Another party-popper is John’s collection of Marlon Brando performances, starting with “The Men” and running through Marlon’s tilts with Tennessee Williams (“Streetcar Named Desire”) and Shakespeare (“Julius Caesar”). Says John, “Brando is a great actor—one of the greatest. That’s why he’s so easy to imitate.”

Mrs. Kerr is inclined to tighten a wifely rein when these performances threaten to bring down the house. Restraint is applied only by means of a lifted eyebrow or an unobtrusive gesture. Then John, an easily contained type, promptly drifts over to a corner and becomes a sterling audience for some other party-circuit performer.

There is one additional fact to be told about this man who reads Russian novels in the original, who is as much at home in London or Paris as he is in New York, and who has, from boyhood, known most of the theatrical greats on a first-name basis—he likes to dunk doughnuts in steaming black coffee.

If John Kerr sounds good to you, you might write to M-G-M and ask them to cast him as Peter McKenzie in “Something of Value.” He’d be perfect in the part.

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE MAY 1956