Hugh O’Brian: “When There Is No Happy Ending . . .”

Hugh O’Brian was strolling idly across the wide green lawn in front of the summer theater at Santa Barbara when he first saw Linda. It was a warm, lazy afternoon in early June. He’d been looking the place over and wondering if he’d ever get a chance at a good part, when he spotted her. She stood talking with some friends a little way off to his right, and here was something about the way she smiled, about the way her long blond hair glistened in the sunlight, and the comfortable feeling her easy, natural laugh gave him, that made him want so much to meet her. All he knew about her was that she was an apprentice, like himself, at the theater; he didn’t even know her name.

Hugh had always been reserved when it came to girls, afraid he couldn’t please them because he had so little money in his pockets. He’d saved only fifty dollars to see him through the whole of this summer, budgeted from busboy work in the noisy cafeteria at Los Angeles City College, where he’d been studying. And then, as he stood admiring her, he saw her turn and walk toward him.

“Hi, I’m Linda,” she said, holding out her hand. “We’ve never met.”

Hugh was startled for a moment. Then he grinned back. “Hello, I’m Hugh.”

“Oh.” There was a trace of disappointment in her voice. “Hugh’s such a formal name. I’m not going to call you Hugh all summer long. I’ll call you let’s see . . . ?” Her voice trailed, then she clapped her hands. “I have it,” she said triumphantly, “Hughie! Hughie’s such a nice name!”

Hugh swallowed hard. He hadn’t heard anyone call him Hughie since the day back home in Winnetka, Illinois, when he’d kissed his childhood sweetheart, Mary, goodbye, and gone off with twenty other guys for Marine boot camp where nobody even considered a fellow’s first name. In the Marines you were either a serial number or “Hey you!” Later, while he’d been out on a field trip, Mary had gotten spinal meningitis, and before he could return she had died suddenly. Somehow, after that, life had never seemed quite so meaningful. There’d never been any other girl.

Linda, he noticed, suddenly smiling down at her, was shorter than Mary. She was just eighteen, straight out of an Iowa town something like his own home town in Illinois. She seemed so friendly that he asked her to have coffee with him and found himself talking easily to her, telling her about his ambitions in the theater and how much he wanted to learn this summer. Suddenly he noticed that the coffee shop was almost deserted and that it was getting late. But by then they’d already become friends.

All through those first weeks they built and painted scenery together, repaired broken furniture for the prop man and sold soft drinks in the lobby during intermission. They never formally dated, but Hugh would often walk Linda home to the old-fashioned frame boardinghouse where the girl apprentices lived; and then amble on in the blue-white summer moonlight to the cellar of the Hotel Loberio where the boys shared a squad-room and slept on secondhand army cots.

And each time, all Hugh could think about on his way home was Linda. He would think of the things they had done together that day, of their yearning to play more important parts in the summer theater’s productions. They’d both played extras in a couple of quick crowd scenes; but that was all. And as he washed his socks, he thought, she has talent, Linda has. And he wondered if she were thinking of him as often as he was thinking of her.

Then, one night in early July, as Hugh was walking home to the Hotel Loberio, he passed a jeweler’s window, and a gleaming silver wristwatch caught his eye. He stopped to look and, in a corner of the window, noticed a delicate gold charm bracelet. A card in front of it read “Special Sale,” but no price was listed.

All through the next day he couldn’t get the bracelet out of his mind. Maybe if he watched his money very strictly, he could buy it for Linda. He wanted to give her something. She had been so thoughtful, often bringing him homemade peanut-butter sandwiches from the girls’ residence for a snack between their chores. “Out in Iowa,” she would say, laughing that wonderful easy laugh of hers, “we don’t let men starve!” Other times she would make a thermos jug of ice-cold lemonade for their afternoon break.

Hugh liked the way Linda didn’t try to make a “thing” of their relationship. She just let it happen.

Finally, toward the end of the week, he decided to price the bracelet. The bald-headed jeweler, his silver-rimmed eyeglasses halfway down his nose, told Hugh it was a ten-dollar bracelet, now selling for $4.98. But even the cut-rate price seemed too costly for poor Hugh, so he thanked the jeweler and left.

All that night Hugh dreamed of the bracelet, and when he got up the next morning he decided to buy it. Something about it haunted him. It seemed somehow that Mary was telling him to be thoughtful and to think of Linda. He went to the jewelry store at noon, plunked down a hard-earned five-dollar bill and asked the jeweler to wrap the narrow cardboard box in some pretty gift paper.

When he returned to the theater that day, Linda rushed up to him, her eyes wild with excitement.

“Hughie! Hughie!” she bubbled. “You’ve been cast! You’re in the next play. A speaking role! You’re going to play the rancher in ‘Of Mice and Men!’ Oh, Hughie, I’m so happy for you!”

Hugh was stunned. He didn’t know what to say. Finally he asked, “Did you get a part?”

“No,” she said softly, adding, “but that doesn’t matter. You did! Come, look, they’ve just posted the casting notice on the backstage bulletin board.”

Unable to hold back, Hugh suddenly let out a “Yippee!” and the two of them, holding hands, ran over across the lawn toward the theater barn. After looking at the notice, they sat down outside near a patch of wild flowers. “If you’re good in this part, Hughie, every talent scout in ae will hear about you,” she said.

It was then that Hugh lifted the thin silver-wrapped box from his khaki shirt-pocket and handed it to Linda.

“What’s this?” she asked, bursting with curiosity.

“Something . . . something I want you to have.”

“Oh Hughie,” she said, throwing her head back in surprise. She knew he had little money for gifts. In fact, whenever they went out for an ice-cream soda or a hamburger after the show, she’d insist on going Dutch treat. She’d told Hugh her father sent her a nice allowance every week, because she hadn’t wanted Hugh to scrimp and spend money because of her.

She started to unwrap the box and suddenly, without reason, she stopped. The two of them looked into each other’s eyes for a minute. Then she began to speak. “Hughie . . . oh, Hughie,” she said softly as she started taking out the bracelet, “you’re . . . you’re just wonderful.” They were silent for a moment, then she said, “I’m . . . I’m going to miss you when I go back to Iowa.”

“Do . . . do you have to go?” Hugh kept his voice low so she would not sense his unhappiness at the thought of her going.

“I . . . I think so.”

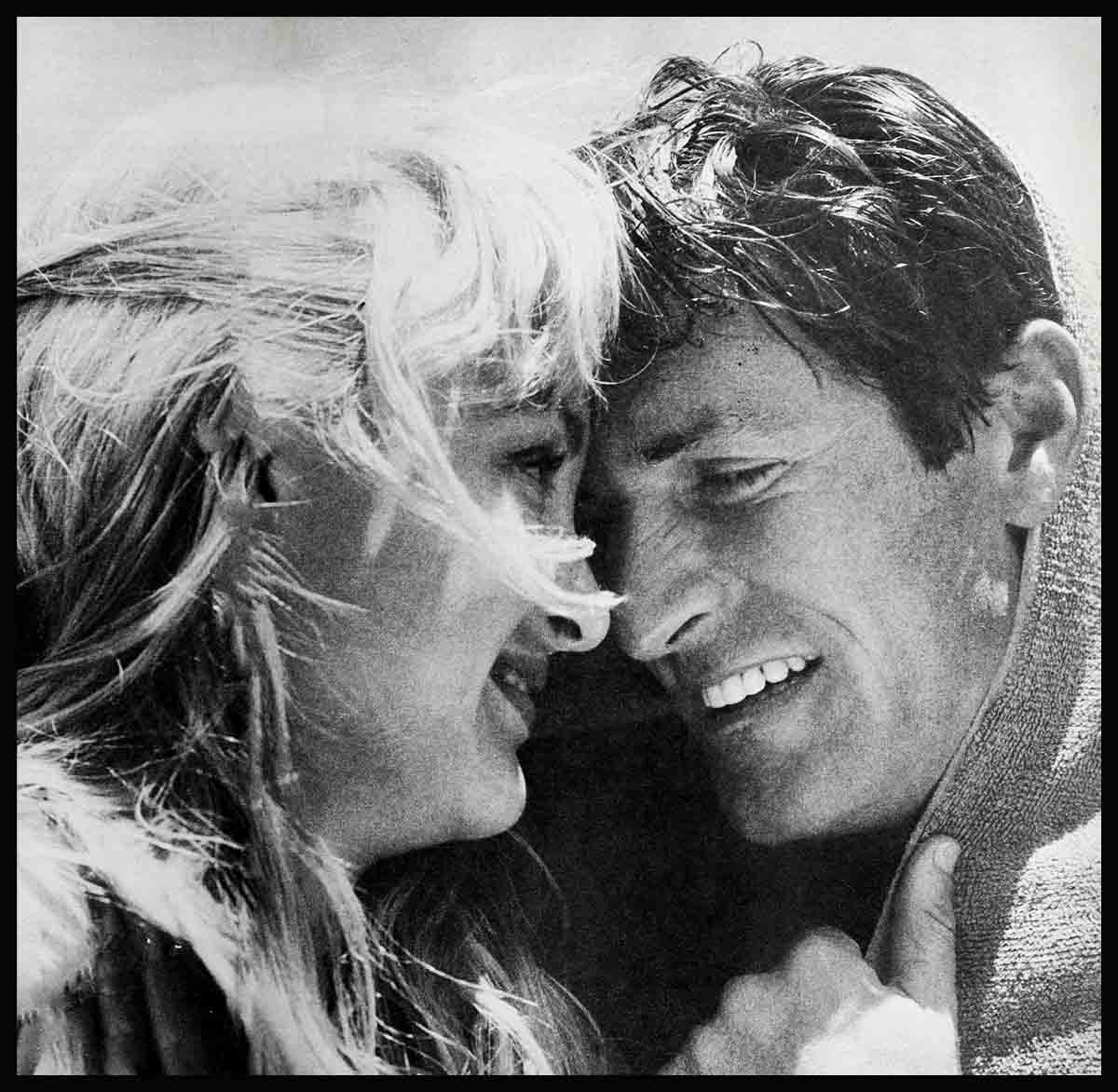

“Oh, Linda . . . I don’t know why you can’t . . .” but he didn’t finish the sentence because, suddenly and uncontrolably, in the middle of that lazy summer afternoon, with the warm, honey-colored sunlight haloing her silky blond hair, Hugh leaned over and kissed her lightly, tenderly, on her small pale lips.

“I’m sorry,” he said afterward, turning his face away in embarrassment, “but . . . you looked so beautiful in the sunlight.”

Instead of speaking, she leaned over and kissed him. And he smiled.

Then he helped her fasten the bracelet on her slim, sun-tanned wrist. “I knew . . . I knew from that first day we met that you were going to be somebody special,” she whispered.

Hugh tried to answer but he couldn’t. He couldn’t imagine anyone so sweet, so pretty, caring so much for him—a hardbitten leatherneck sergeant with a chip on his shoulder, who felt life had cheated him when it took away his childhood sweetheart.

Then, as he sat thinking, he felt Linda lean over and rest her head against his shoulder. “Hughie . . . Hughie . . . ,” she was whispering, “I can’t help it. I think I’m falling in love with you!”

From then on, they spent every free moment together. They found they had much in common. She loved Broadway-musical record-albums, and they listened to them backstage at the theater before curtain-time. Their favorite album was “South Pacific” with Mary Martin and Ezio Pinza. They talked about careers in movies or on the stage and exchanged news from their home towns. They showed one another snapshots of friends and relatives and family.

And the summer passed like a day.

On Labor Day night, after the final performance of the season, the theater managers arranged a farewell wiener-roast and clambake for the cast, crew and the apprentices at the nearby beach. The night was cool and a full moon cast a diamond-bright glow in the sky. One of the cast members brought a portable Vic, and everybody danced barefoot in the white sand. Hugh and Linda danced for a while, then ate charred frankfurters and toasted a few marshmallows.

“Want to walk a little?” he asked her. It was shortly after midnight.

“Sure,” she said, her eyes glimmering in the white moonlight.

Hand in hand, they walked by the shore, Hugh carrying an old Army blanket with him. And when they came to a secluded spot surrounded by craggy rock formations, Hugh spread the blanket on the sand, and the two of them sat down and listened to the waves crashing against the shore.

Then Hugh turned to Linda and took her hands in his. “I . . . I never knew I could ever be so happy . . . again,” he said tenderly. And it was then he told her of Mary, of their hopes and their young love, and of how she had died. They both cried a little together and then, from exhaustion, they both fell off to sleep.

They awoke to the mournful sound of the sea. The night seemed unusually black around them, and then they noticed that the moon had disappeared behind the steep rocks. Hugh looked at his luminous military wristwatch. It was two o’clock.

“Linda,” he said in a groggy voice. “We fell asleep. . . . Are you chilly?”

She nodded.

The two of them arose, and Hugh picked up the wrinkled wool blanket. Shaking it thoroughly in the ocean breeze, he wrapped it tightly around Linda. “I don’t want you catching cold,” he told her.

For the first time in his life since his Mary had died, Hugh was comforted by an intense nearness, a oneness with another person. Hugh told Linda this as they walked along the edge of the beach with the waves tossing behind them. Slowly the moon began to reappear. “I . . . I wish I could reach out,” he said, thrusting an arm upward, “and give you a piece of it. You’ve brought me out of myself, out of my sadness.”

Hugh stopped and put his arms around her blanket-covered shoulders. And he kissed her gently.

“Will . . . will you marry me, Linda?” he asked.

Her eyes, seeming so large and hopeful in the moonlight, looked directly up into his. “Yes Hughie! Yes,” she said softly. “I will.”

That next day Linda left for Iowa on the afternoon train. She had called her folks long-distance that morning and begged her mom to allow her to stay a few days longer. But her mother was adamant. Linda had been away long enough, and she was ordered to be home as planned.

That morning Hugh bought her a bouquet of white carnations, a pair of Japanese “kokeshi” dolls with wooden heads that bobbed if you tilted them, and a secondhand copy of Lord Byron’s love letters printed on an elegant ivory vellum. He carried her suitcases to the beat-up Plymouth he’d borrowed from one of the other apprentices, and he took her for a ride around Santa Barbara before train time. He promised her he would come out to Iowa over Thanksgiving and visit her and meet her folks. Meanwhile, they agreed to write letters every day. And when the time came for Hugh to take her to board the train, he said, “Remember, Linda, we’re just saying so long. This isn’t goodbye.”

She nodded, and he carried her suitcases to the coach-car of the train, where they kissed for the last time. The conductor’s “all aboard” echoed through the station, and Hugh and Linda parted. As he watched the train shrill down the track, Hugh dreaded the coming months without her.

He enrolled for his sophomore year at Los Angeles City College, and he worked many long hours after school at odd jobs to save all his earnings for the day he and Linda would be together. They wrote to each other regularly, and, early in November, she suggested he wait until Christmas before he visited Iowa. He wondered why she wanted him to prolong his dreamed-of trip, but he listened to her request and waited until the week before Christmas. He had lined up a ride with a classmate to Chicago, and from there he planned to hitchhike alone to Iowa.

He bought Linda a rose-beige cashmere sweater and an expensive vial of Chanel perfume. He had a gold heart inscribed for her charm bracelet: For Linda, it said, With All My Love This Christmas and Always, Hughie.

Then, three nights before Hugh and his buddy planned to drive to Chicago, the call came. She phoned his dormitory to tell him the shattering news. He mustn’t come to visit her, she explained, because things had changed. Her parents wanted her to marry someone else. She had gone with the boy before she met Hugh, but she hadn’t thought much about him. Now, under family pressure, she felt helpless. She didn’t really know how she felt.

“I’ll come and get you out of it,” Hugh said firmly. “I’ll tell them all you’re marrying me!”

“No.” Her voice over the telephone sounded almost unfamiliar. “It’s too late, Hughie. I’ve given my consent. I’m . . . I’m just a small town girl . . . and you . . . you’re going to be somebody. You’re going to be a big actor. I don’t want to be in the way.”

“But, Linda,” he said brokenly. “I . . . I love you.”

“And I love you, Hughie,” she said. “But I . . . I can’t marry you.” Then she admitted, “I’ve gone with Timmy since we were kids, and I can’t back out of it now. There’s nothing I can do. I’m afraid . . . this seems . . . best.”

He didn’t know if he were wide awake or in a dream as she spoke to him. “Hughie,” she added before saying goodbye, “thank you for a wonderful, wonderful summer. . . .”

When he clicked the black receiver onto the cradle of the wall telephone in the dormitory hallway, Hugh decided to make the trip to Iowa nonetheless. Perhaps he could still persuade her to marry him.

But making the trip was a mistake. When he got to Iowa he visited her and gave her the gifts he’d bought her, but Linda wasn’t the same. She seemed almost a stranger—cool and distant. She told him, yes, she loved him; but she felt closer to Timmy. She’d known him all her life.

Hugh left the snow-covered fields of Iowa and hitchhiked to Chicago. He spent Christmas Day itself in a lonely YMCA; then he hitchhiked, depressed and down-hearted, to Los Angeles.

He simply couldn’t figure it out. I guess love is that way, he decided. There are no mapped-out formulas for anyone.

Today, Hugh says, “It still isn’t easy for me to receive a Christmas card from Linda or a get-well note when she reads in a gossip column that I’ve had the flu or some eye trouble. I can’t help but remember those sweet summer days we spent together, but I’ve made up my mind about one thing: To find love, you have to be open for love. You have to accept the past for what it was. You can’t live in it. I’m a man who needs love—and I’ve been lonesome long enough!”

THE END

FOLLOW HUGH’S ADVENTURES AS “WYATT EARP” ON ABC-TV, 8:30-9 P.M. EDT TUESDAYS

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE AUGUST 1959