“Oh My God, I Can’t See”

It was a cry out of a nightmare.

“I can’t see! Oh my God, I can’t see a thing!” Mrs, Robertson, hearing it in the kitchen, hastily set down the bowl of pancake batter she was mixing for breakfast. She ran to Dale’s room. His father, dressing for work, hurried from the bedroom.

“Dale, honey,” his mother cried anxiously, “what’s the matter?”

“What is it, Son?” his father asked. “Did a bad dream scare you?”

Dale was sitting up in bed, shock and terror on his face. The room was in broad daylight, the shades hardly drawn down. The chest of drawers, the chair, the books and scattered possessions of a thirteen-year-old boy, were sharply outlined in the morning sun. His mother and father stood at the doorway, but Dale’s eyes, so clear blue and wide open, did not turn to where his parents stood.

AUDIO BOOK

His mother’s hand went to her mouth in fear, clamped tight across it to hold down a cry.

“What happened, Son?” his father asked again. But his wife shook her head and looked at him with anguished eyes.

“We—keep forgetting—he can’t hear us. Mel!” The terror cracked in her voice. “Mel, what’s happening to our boy?”

“Easy,” the father murmured, “easy, dear, try to take it easy.” He bent and put an arm around Dale’s shoulders so his lips almost touched his son’s ear.

“Dale— tell— us— exactly— what— happened.” He spoke very loudly and spaced each word for Dale to catch some sense and meaning.

Only a few weeks ago the first blow had struck—that time there was no warning either. It had come just as suddenly. When his father spoke to him, Dale did not answer.

“He isn’t even aware that anyone is making a sound,” his mother sobbed. When the doctor finally came, an hour later, and examined the boy he could find no reason to explain the sudden loss of his hearing.

That was only weeks ago—and now this. . . Dale, speaking slowly to them, trying to explain. “I open my eyes, but everything is pitch dark,” he was saying. His voice was nearly toneless. “I—I blink them—and try to see—and nothing happens. I—can’t even see my hand. I know it isn’t the middle of the night—I’m blind.” He said it again, softly now. “I must be blind.”

His mother pressed her boy’s hand against her cheek. If he couldn’t see her, or hear her, at least let him feel her touch and know that she loved him. Loved! If she could go blind for him. . . .

Oh dear God, she prayed, help him. Help him! He’s only thirteen, he’s still a child. Please, Lord, don’t make him carry such a heavy cross.

The doctors came—many of them—but they went away baffled. Thirteen—deaf and blind—and no doctor could tell them why. From specialist to specialist they took the boy, but none could say what had happened. After the examinations, the tests, the questions and the probings, the verdict was always: “Incurable.” Thirteen years of age, healthy–and incurably blind, incurably deaf.

The only theory any doctor had was a vague one: perhaps both disasters were the result of something contracted while swimming in one of the creeks or ponds he’d always managed to find—water holes never meant for swimming, unprotected and breeding places for germs. But what germ did this to him? Again they were up a blind alley. No man-made machine or graph or test tube could give the answers they needed. He was beyond their help. And his mother, no longer able to control her emotions, wept bitterly.

The days after were long; there seemed to be no time, no change. Just blackness. And for Dale, those first few days after his world went dark, he lived in an aura of confusion. His shin knocked against an end table and it was not the ache that hurt, but that he knew he had knocked off the table lamp. He could not hear his mother’s concern—not for the lamp, he knew, but for him—yet he could feel it. And he sat still after that, and tried to understand what had happened to him. “It’s a nightmare from which I’ll surely wake—soon,” he told himself. But the nightmare continued and reality hit home. It was as if he saw his mother’s tears and heard her sobs, although he could do neither.

He learned to sit for hours on the front porch, wrapped up in his own private world, a world which he was learning to make. He could not share it with his family. Yet, he wished he only could. In the beginning, they had been afraid to let him try anything on his own. But then, they merely stood aside—and each moment they wished and waited and worried and watched—this he knew.

As he sat there, day after day thinking, something new happened. He began to feel something new, something which he could only realize much later, when he was much older. Even in darkness, he learned that life had its beauty. That life was worth struggling for, and little by little, he began to turn his handicap into a game.

“How long does it take me to cross over to the other end of the porch?” he challenged himself. “How long will it take me to get dressed this morning?” he asked. Slowly, with patience, he would count in a steady beat—because he could not read the clock—as he put on his shirt, as he tied his tie. And he would find an excitement when he would beat his yesterday’s count. “Only 193 beats to put on my shirt this morning,” he would inform his father at breakfast. He felt a pride and a feeling of achievement.

With time, he began to make plans . . . wonderful plans, as he sat on the front porch. He began to learn things far beyond anything printed in his ninth-grade textbooks which sat unread on top of the desk in his bedroom. He should have been in school—his mother and father had looked forward to it so much. That’s why his folks had moved from their farm into Oklahoma City, why they cheerfully went from their spacious place to a two-bedroom bungalow.

“We want our Dale to have a fine education, Mother,” his dad used to say. “It’s worth the cramped living.”

Now, instead, he decided on an occupation. He would become a writer—he would earn his living by writing. If he couldn’t see or hear, he could still think. He’d find a way—some way—to put all the thoughts that spun through his brain down on paper. He’d write stories and plays and books. About what? About the colors he used to see, the green of the grass, the rich red-brown of the earth, the pale blue and white of the sky, the brilliance of the stars. He’d write about what he had heard: the whinnying of a horse, the cackling of chickens, the sounds of dogs barking, the noise he made when he went swimming and dived into the water with a splash. The music of birds singing and the drip, drip of rain on the roof. All these things he still “saw” and “heard” in his mind’s inner and perfect eye.

And he’d describe the wonderful smells of the world. The clean, sweet outdoors after a rain, with the trees glistening as drops hung to them. His mother’s cooking; and the way she smelled when she dabbed on perfume the times she dolled up to go to town. And in his stories, he would talk about love. Love was a touch, a pat on the back, a playful poke, a tender tap. Love was all around. He knew that, because he could feel it when his dad came home at night and patted his shoulder. When his mother stopped her chores and gave him a hug. When his brother brought him a chocolate bar and threw it on his lap. He knew he was loved.

And perhaps it was this feeling that helped most, that long year that passed. A year—365 days. He grew to be fourteen, to be taller and slimmer and his shoulders, even without exercise, were broader. He could tell because his suit jackets no longer fit. And, though he could hear no better nor see no more, he grew in courage. It was easier for him than for his family, for he had never heard the word incurable—and they had. Perhaps that’s why; what happened afterward might never have happened—except that he believed, with all his heart and soul, he would get better.

It was a cool Saturday afternoon. He was sitting on the front porch, on his favorite chair, a big comfortable rocker. He was daydreaming as usual, when he felt a hand on his shoulder. It was a stranger. He could not tell whose hand it was. He felt the stranger lean over close to his ear and shout, “Hello,” so loudly that even he could make out the word. He tried to listen, as he felt the lips pressed close, and then, miraculously almost, he heard the words, “Pray . . . pray . . . pray. . . .”

He felt the man’s face with his hand, and his own face moved into a broad smile. He remembered this man. He was not a stranger after all. He was Brother Murphy, the preacher at their church. A picture flashed through his mind, a kindly face slightly wrinkled around the eyes, and his hair—it was graying at the sides—it gave him a distinguished look. “Why does he always wear a business suit?” he d asked his mother when he’d first met Brother Murphy. Because once he had seen a picture of a preacher in a book. The ma? wore a long, black frock coat and he’d asked, “Mommy, why doesn’t Brother Murphy ever wear such a fine coat like that?” She’d told him, “Dale, it doesn’t matter what Brother Murphy wears on the outside, it’s the way he feels inside that counts.”

Now, as he sat thinking back, he could sense that Brother Murphy no longer stood above him. He reached out his hand and touched the padding on the shoulder of the preacher’s coat. He understood then that he was kneeling alongside him.

Gently, as if not to frighten him, the preacher took one of his hands and then leaned over. He could feel the movement of the preacher’s lips pressed to his ear.

He could not tell, at first, what he was saying. Then he knew. He was praying. How long they remained there—the preacher on his knees, a boy in his rocking chair—he did not know. He only knew that he felt a strength. He did not know how long they prayed; he could not count the times he said, “God, oh, God, help me.” But he knew, even though he was only a simple boy, that God was hearing the prayer. He never thought to question, ‘Why should God listen to me, Dale Robertson?” He never thought, “With the things He has to do, why should He take time?”

I He didn’t have to ask, because he knew that God was hearing him.

How swiftly the time seemed to go. He prayed for days. It seemed that the preacher never left him. Then, one evening, just before sundown, he opened his wide blue eyes, and blinked them quickly, then he closed them and opened them again. He did not want to cause alarm to his parents. He didn’t want them to become excited over nothing, but if seemed he could see just slightly, just faintly the form of a man kneeling beside him. And he heard him speak words. The words? Were they only in his mind? Could he hear the words more clearly? Was someone whispering, “Dear Lord, we humbly ask Thy help. . . . Amen.”

“Amen,” he whispered softly, testing the sound of the words against his ears. “Amen,” he said and with those words—after 373 days of darkness and after being 85 percent deaf—Dale Robertson began to hear and see again.

Since that day, Dale has traveled a long road. He has known war and the pain of serious wounds. He has known moments of personal unhappiness. He’s known disappointments and struggles. Yet, despite them he has learned to make the best of himself. “And never once,” he says today, “have I lost faith.”

He doesn’t often speak of that year’s experiences, few friends are even aware of them, yet he relives those days in some way every day of his life. They have taught him that he will never walk in darkness no matter what happens, for God. in His infinite wisdom, offers Mercy. It is up to man to see it.

As Dale says, “It took blindness to teach me to see.”

THE END

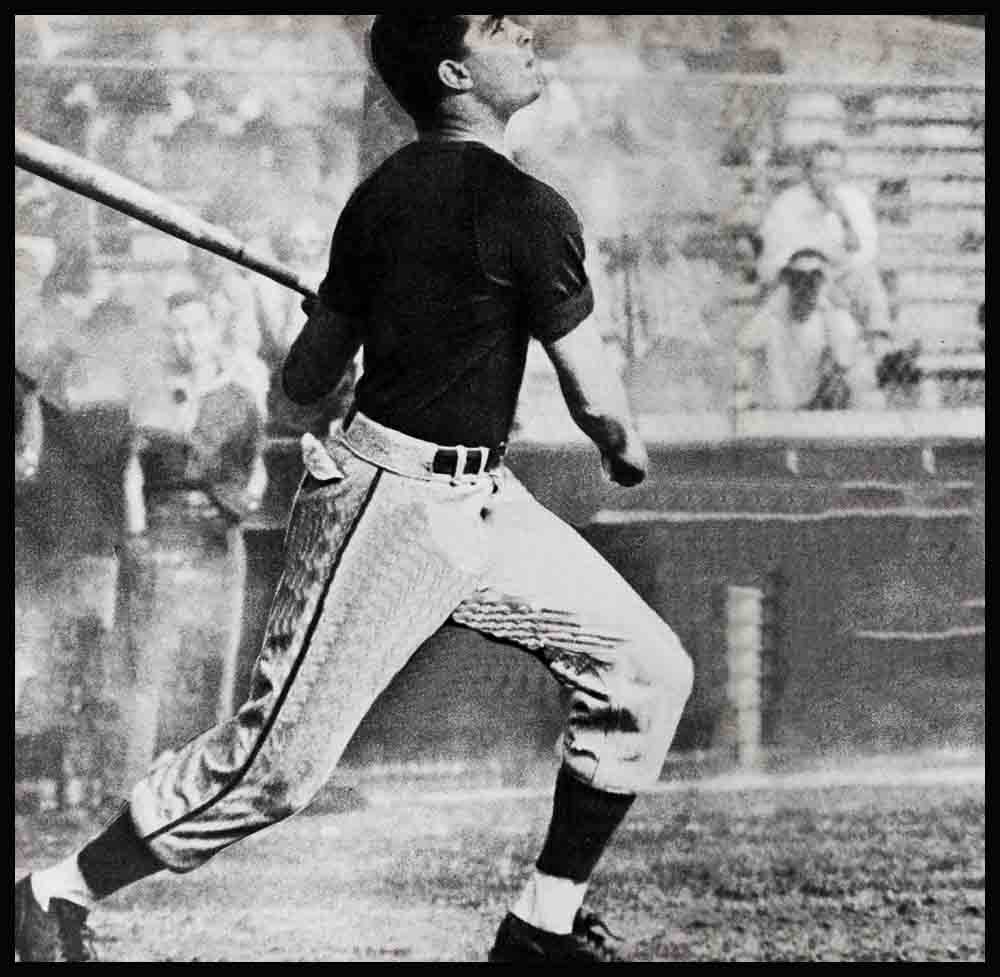

See Dale on NBC-TV in “Tales of Wells Fargo,” Mondays, 8:30-9:00 P.M. EST. He’s also in “Fast and Sexy” for Col.

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE JANUARY 1961

AUDIO BOOK