Hard-Luck Anne Francis

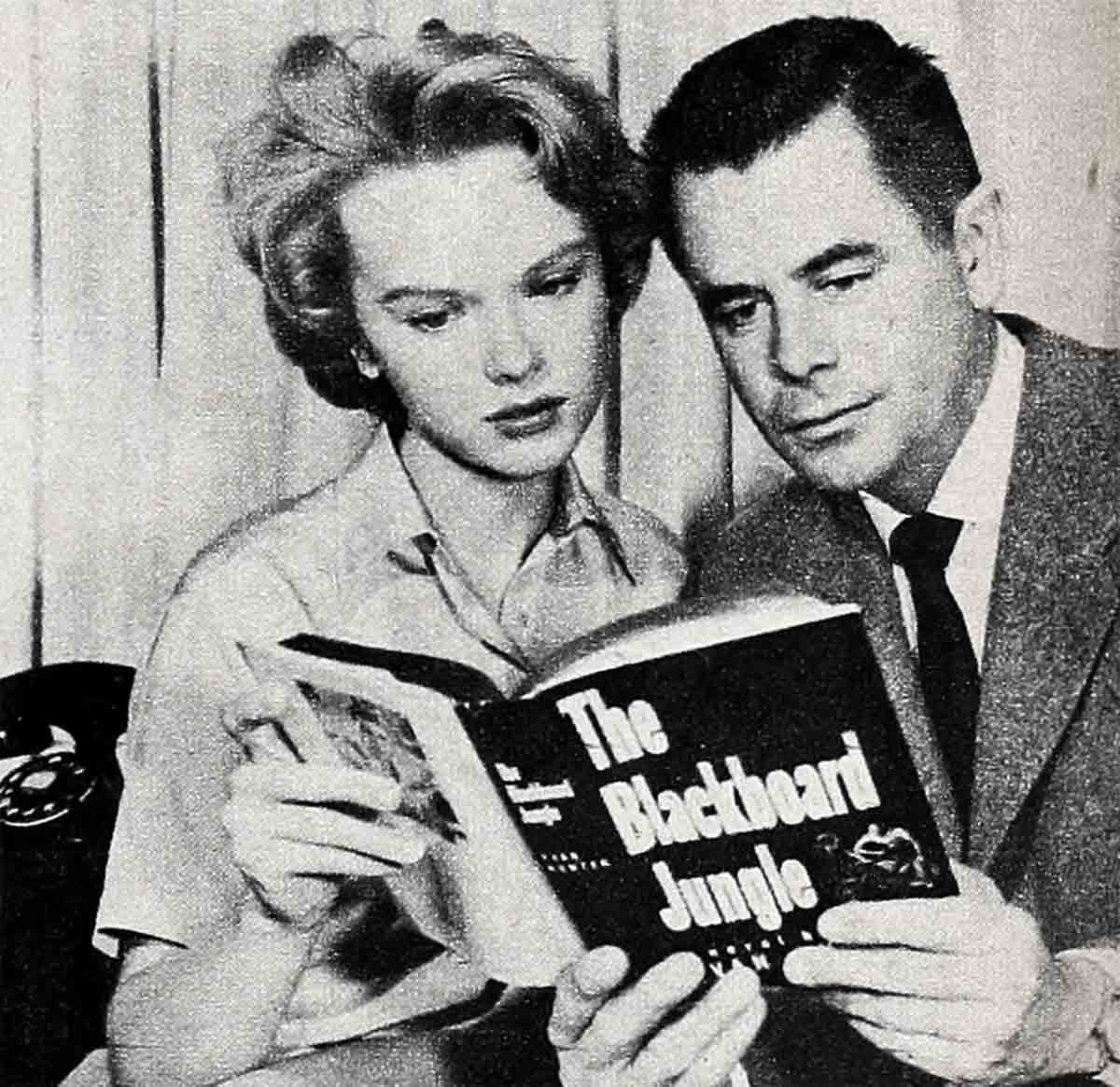

On Wednesday, April 6, 1955, Anne Francis took the witness stand in a Santa Monica courtroom to ask for a divorce from Bam Price, on the grounds of mental cruelty. “My husband would not allow me to have a maid or a cleaning woman during the entire period of our marriage,” she testified. “He felt that it was important for my character to keep house and organize my home. However, during this period I was working from December, Nineteen Hundred and Fifty-three, to December, Nineteen Hundred and Fifty-four; I did seven. films. This entailed twelve hours of work—at least—on the set each day.”

Her voice was even, but her eyes were unhappy. “I was unable to keep up the home,” she went on. “I was found fault with because I was not able to do this. I was told that I was inadequate as to keeping the home and I was never able to catch up with the work. As a result, life at home was in a state of confusion, upset and frustration.”

At the conclusion of the trial, Anne slipped from the room. The decree was to be entered. Her former name, Anne Francis, was to be restored to her. Astonished friends asked: “Now what’s in store for Anne?”

Anne had nothing to say, no explanation. Not the type to turn impatiently to a gay whirl of night clubs for solace or to rush into a new romance as others might, she simply went away since there were no immediate pictures on her schedule. Her friends knew that there would be no sad songs upon her return.

“Through the bad times and disappointments, Anne always shows a remarkable patience, the patience of someone who knows how to wait for happiness,” says one of her friends. “It isn’t that she’s hurt less than anyone else would be. It’s more of a faith in the future.”

Anne’s waited before. There was a period which, as an actress, she spent away from the cameras. It lasted over a year, which might seem more like a century to a motion-picture star who wants nothing more than to act.

True, she had a contract at 20th Century-Fox and three pictures to her credit. But then came the lull and she watched choice roles being given to others because, she was told, she wasn’t the right type. You could have named almost any type. Anne wouldn’t have been it.

In earlier days she might have joined the nearest sympathizer in a sobbing session but she trusted in luck and instead said, “When the siege is over I’ll get my chance to show what I can do! I’ll be rested and ready!”

As Anne had said, her luck did turn—professionally. “It isn’t easy in a dark moment to convince yourself that everything will be right again,” she admitted. “It’s not easy to learn to hold back a flood of self-pity and self-doubt during the trying times. It’s difficult to think clearly when you’re certain you have every reason to be depressed. You find that you’re not reciting casual conversation when you say to yourself, ‘I must be patient.’ ”

Anne was exposed to this philosophy early in life. Her mother had three sayings. Her daughter grew up with them. “It’s always darkest before the dawn,” Mrs. Francis would say. Or assure her with the words, “Things always work out for the best,” or “Remember, luck is just around the corner.”

“To this day, they’ve remained in my mind,” she says. “And as I’ve lived my life, I’ve learned to call upon them.”

Anne was born in Ossining, New York, a small town outside of New York City. She was a healthy child and her family life couldn’t have been happier.

The beginning of her career was effortless. When she was six, friends suggested to her parents that she might do well as a model. While they were in the city one day, her mother decided to stop by the John Robert Powers agency.

Mother and daughter walked into the reception room to find dozens of people with the same idea. Mr. Powers, however, happened to be conferring with one of his employees and, en route back to his office, passed the reception desk. He glanced toward Anne. “We’ll take this child,” he said.

Anne became a Powers model. Just like that.

Luck seemed to be with her all the way. Soon she went into radio and television, later the stage. A search was being conducted to find a replacement for the girl who portrayed Gertrude Lawrence as a child in “Lady in the Dark.”

Again luck beamed on Anne. While her reading undoubtedly pleased the executives making the selection, she recalls they were more jubilant over the fact that she was the exact same height of the girl who was leaving the cast. She got the role.

Self-confidence and peace of mind come easily when things are going right. But then, as to all children, the awkward age came.

“It’s a sad time for everyone, but it’s like the end of the road for a professional child,” she recalls. “Suddenly, you’re all hands and feet and they’re attached to arms and legs that seem only to hinder every move you make. Your training in grace and stage presence doesn’t help.”

As far as Anne was concerned, she couldn’t age fast enough. Photographers and television casting departments were definitely not in the market for an ugly duckling.

The logical move was to return to radio where she might temporarily hide behind a microphone. Just about this time, Anne learned of an audition being held for a role on the radio serial, “When a Girl Marries.”

Several days before the audition, she awoke feeling miserable. The doctor announced that she had a strep throat.

And each day her voice sounded more like a fog horn and she became more upset. When the day of the audition arrived, her mother said, “Something tells me we’ll be sorry if we don’t go.”

They went. Anne read, sounding for all the world like Tallulah Bankhead with a cold. When she’d finished, they returned home to bed.

The news came later, a phone call. The part was Anne’s. “Your interpretation was fine,” she was told. “And by a real stroke of luck, your voice matches.”

It was then she learned that the actress who had been playing the role had an unusually husky voice. Anne’s was so similar that the sudden change in players would hardly be noticed. Eventually her normal tones returned. But it happened gradually and she was given ample time to establish herself in the characterization.

At fifteen, Anne made a screen-test at M-G-M’s New York office, was signed to a contract and sent to Hollywood. During the year she was there, she was given one small role in a picture called “Summer Holiday.” She worked for two days. The rest of the time she went to school and waited for movie assignments that never came. However, before many months had passed, she was certain of one thing: She wanted, with all her heart, to become a motion-picture actress.

It seemed that Anne’s heart was destined to be broken. Her option was dropped and she returned to New York, where it took another year to re-establish herself in radio, television and summer stock. More time was required for her return to movies. “And when it happened,” says Anne, “it was completely by—well, chance is a good word!”

An independent production company was planning a film to be made in the East. There were two roles which interested Anne: one was that of a shy girl; the other, a brazen hussy. She stopped by the company offices and talked to the man in charge of casting. “We’ll probably call you,” he said as she left. But there was no call.

A few weeks later, while making her rounds of the casting offices, Anne found herself in a familiar place. Looking around, she discovered that she had returned to the scene of the independent production company. When the casting director appeared, she spoke her piece. “You don’t want to see me,” she told him. “I’ve been here before.”

No sooner had the words tumbled out than she noticed Paul Henreid standing in the doorway of an adjoining office. He was to be the star of the picture. The director was with him. “Come on in,” he said.

They sat and talked for a while and Henreid asked if Anne would like to do a screen test for the production. “For which part?” she asked.

“Both,” came the reply.

To her delight and surprise, Anne won the role of the bad girl. To this day she couldn’t tell you how she happened to go back to that office. “I would never have returned intentionally,” she says. “And the casting director later admitted that he would never have called me. He had completely forgotten about me.”

The Henreid film led to still another production being filmed in the East, “Whistle at Eaton Falls.” This one led to the contract with 20th Century-Fox and to Hollywood.

Careerwise, Anne was on top of the world. In private life, she had left behind a broken romance. At seventeen, a time when every girl would like to be loved, she fell in love for the first time.

Her love was a handsome fellow—handsome, unpredictable, and unreasonable.

Soon there were no more clouds—at least to dance on. In her emotional state, her work was being ruined. Scripts were merely conglomerations of words and the words had no meaning to her. One day, after an argument, Anne began to cry in the middle of an important radio show.

It wasn’t easy to reach the conclusion that she’d been in love with the idea of being in love, that she was no more prepared for the responsibilities of marriage than he. She realized that falling in love takes patience, too. Patience to wait for the right man. She thought that she had found him when she came to know Bam Price.

They met at a party. Anne was in the midst of production on “Lydia Bailey.” The picture was in Technicolor and she had contracted a case of make-up poisoning from the heavy applications of grease paint. On this particular evening, she attempted to cover the ailment with more make-up.

Bam had arrived with a couple who were having a quarrel and he spent the entire evening trying to relieve the tension by making up for their lack of conversation.

Anne and Bam were introduced, but they wasted no time in talking to one another. Anne concluded that he was an impossible extrovert. Bam considered her a, painted doll.

A few months later, they discovered that they had both moved into the same apartment building. Their courtship began at the incinerator, where they would meet to dump yesterday’s papers and cardboard cartons. Then they reached the stage where they would go out together if neither had another date. Anne found that Bam had graduated from pre-med school but had become interested in motion pictures while in the service and had returned to classes at UCLA to major in the subject and to take another degree—his Masters.

They were certain that they loved and understood one another—and each other’s work. And on May 17, 1952, they were married.

During Anne’s inactivity in movies, she tried to keep house. Bam was working on a feature-length film, which he had written, directed, produced, appeared in. It represented his thesis for his Master’s degree, and he also hoped to have it accepted for national release. Anne would watch him work and marvel. And sometimes attempt to help. “I’m learning more than I ever dreamed I’d know about the activities behind the camera, every phase of movie-making,” she said proudly at the time.

To all appearances, the Prices seemed to have a good and happy life. Their troubles seemed to draw them closer. There was Bam’s near-fatal illness. They had driven to the desert to celebrate their second wedding anniversary. Then, on a Sunday evening, Bam collapsed and was rushed to the hospital. His condition, first diagnosed as a heart attack, then pneumonia, was critical. He wasn’t expected to live through the night. And Ann, distraught with fear, stayed by his side all through the long siege.

That night was an eternity. The following day, she was told that by a miracle he had passed the crisis. She could only stand there, smiling and crying at the same time.

If anything, Bam’s illness had seemed to strengthen their marriage. But something happened. There are two sides to every story. But both Anne and Bam have remained silent. Except for the court appearance, neither will talk about their failure. They want what’s past to stay that way. They tried. They failed. Neither can take the failure lightly. And now is the difficult time, the time of waiting for the heart to heal, the time again for Anne to be patient.

THE END

—BY ELIZABETH WISE

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE OCTOBER 1955