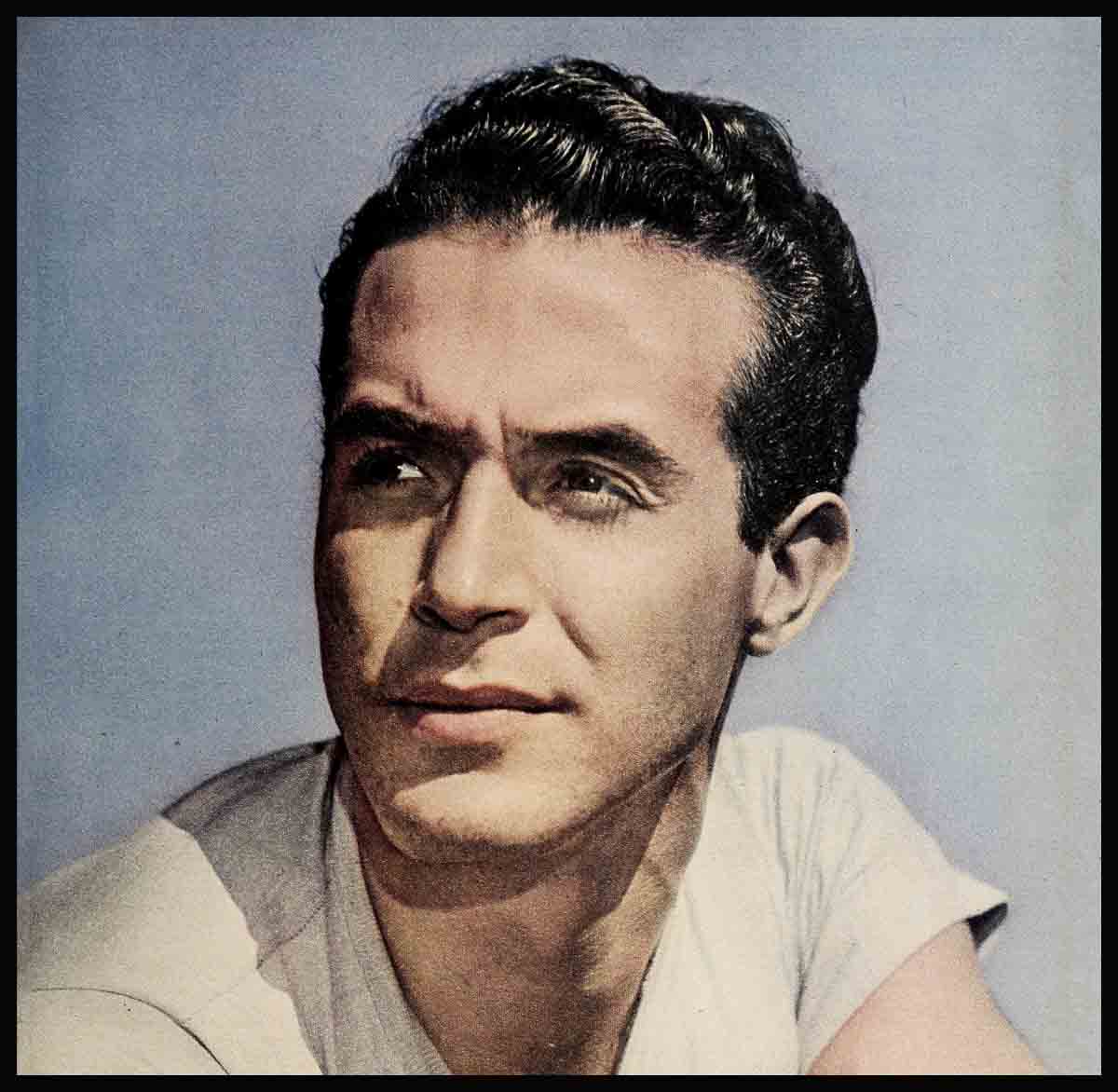

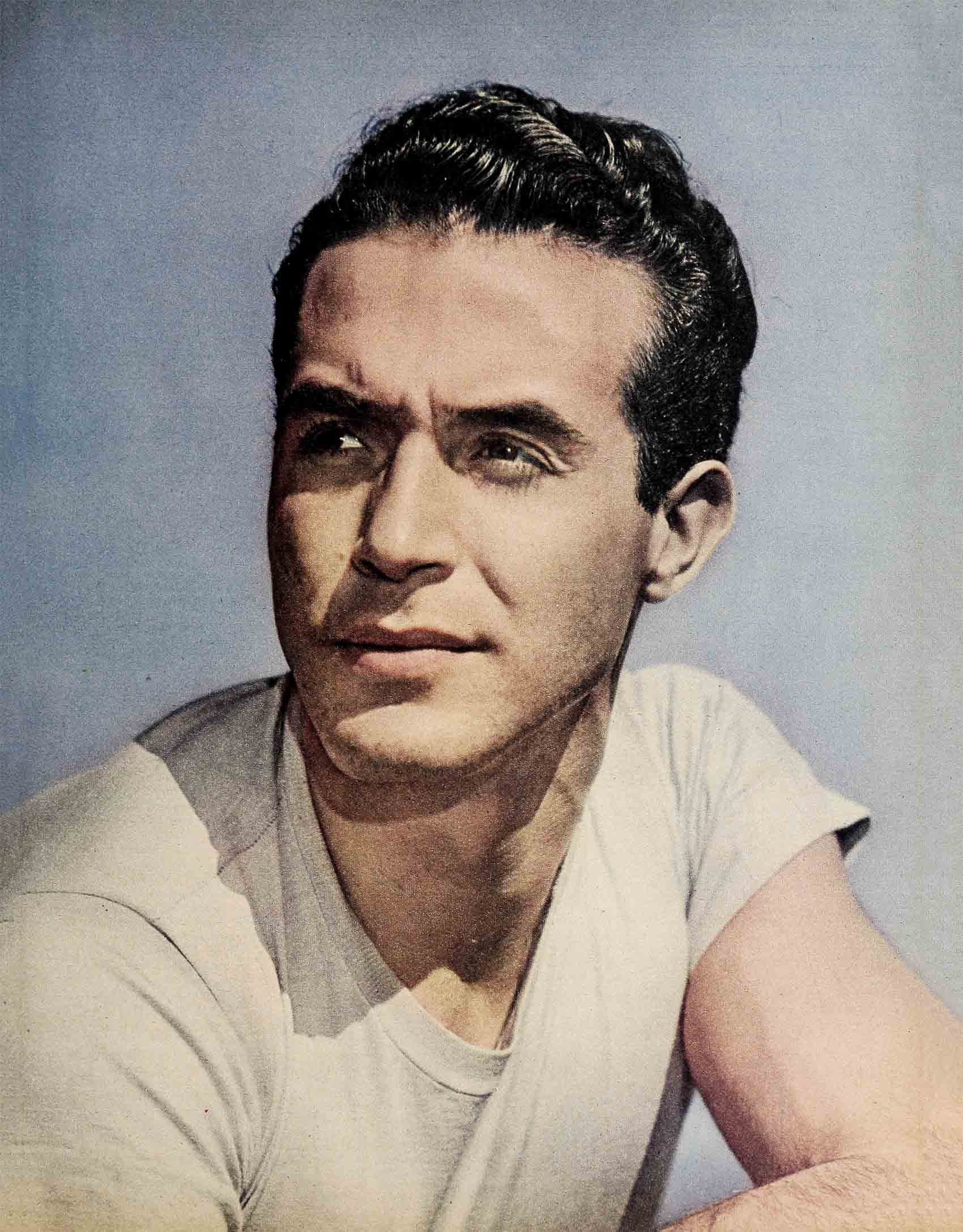

Dark Man In Your Future—Ricardo Montalbán

His name is Ricardo Montalbán. Mont (as in don’t)—tahl—bahn, with a slight emphasis on the Mont.

In the picture Fiesta, he was required to dance a little number with Cyd Charisse called “The Flaming Flamingo,” and to play a terrific concerto on the piano, and to seem as proficient a matador as the men who spend lifetimes practicing.

He also had to act.

He doesn’t look like the typical American conception of a Mexican, but Americans have some funny conceptions. His charm has an effervescent quality about it: he is a bundle of nerves, but they are under control. And he is a genuinely intelligent man.

He remembers being eight years old, and the first plane coming over their little city of Torreon. Everyone stood in the streets and watched it, that first day, because they didn’t know what would happen, and in Northern Mexico, in 1928, one had not seen many flying machines.

Directly over the center of town, the pilot leaned out and dropped a small black object, which plummetted straight down and made a noise and a flash when it hit.

Then the airplane flew away, and there was a great deal of rushing about and confusion. The revolution had come to Torreon.

Every day at noon, after that, for twenty successive days, Ric’s father and uncle would wait in front of the house, searching the sky until the droning speck appeared in the distance. They would shout, “There it is! There it is! Andale!” And mother would round up Ric and his brother and sister and shove them under one of the big beds. It, was all great fun, and Ric was sorry when the plane stopped coming.

Torreon was in a barren part of Mexico, but two rivers ran past it and in the country outside, endless fields of wheat and cotton stretched toward the distant mountains; from the fields gold poured into the town, making it one of the richest cities in Mexico. Here, Senor Montalbán, who had come from Spain, established his department stores.

first bull-fight . . .

It was when Ric was twelve that he spent his first summer vacation at the great Durango hacienda of Senor Gurza, his father’s old friend. Senor Gurza raised That August, Ric saw his first Tienda.

All the neighboring rancheros and their families gathered around the private bullring at the Gurza hacienda, after the noonday barbecue, and Juan Gonzales, the foreman’s son, explained the Tienda to Ric. “It is that you can fight a bull only once,” he said. “After that they know— they shy from the cape. But the Senor Gurza must find out if the little bull is growing up to be a sissy, or if he will be fierce and put up a stiff battle.

“Now, mira, all the little bulls have sisters, and it is known that a bull and his sister always are born the same, with the same characteristics. So we have a trial fight with the little cow, just nicking her a little, not to hurt her, and ‘so we find out. Verdad?”

“Men do not fight cows,” Ric said.

“No. You and I and the other muchachos will fight them. Come along.”

“I? I’ve never faced a bull—or a cow, even. I’d be gored.”

Juan looked scornful. “You have to start sometime. You know the passes, don’t you? You’ve seen fights?”

“Yes, but—”

“Then come on. They’ll think you’re afraid.”

Ric stood trembling in the middle of the ring, watching the young cow—no delicate hers—pounding toward him. He had never realized how much taller a cow was than he, until she pulled up, raised her head and stood glowering at him, for a moment. Then she lowered her head again and charged.

Shutting his eyes tight, because he was afraid to look, he waited until the sound of hooves was almost upon him; then, as he had seen the matadors do, he made a slow wheeling turn to his right, sweeping his cape in an arc as he did so.

The cow thundered past, and in momentary relief, he opened his eyes, waiting for applause. Instead, there was a storm of laughter from the wall, and hoots of derision. The cow had charged behind him—

Fury mounted in him, throbbing in his throat and making his face dark. He faced he ugly little cow again, brandishing the cape wildly, and met her second charge full-face, with his eyes open. He was so angry he forgot to sidestep. The next instant, he was sprawled in the dirt, stunned and breathless, and the cow was worrying him with her horns and a forefoot. A cow-hand distracted her before he was too badly mauled, and he had not been gored. But he was a sorry sight.

Senor Gurza was furious. “You shouldn’t have tried it without practice!”

“I will do this again tomorrow, with your permission, sir,” Ric said. “I couldn’t let a cow beat me in the ring.”

The older man smiled. “As you like.”

After six summers at the Gurza, Ric was a fairly accomplished amateur matador.

But the rest of his early life was mundane enough. He had a remarkable boy’s soprano until he was fourteen, and his voice shattered on a high C one afternoon and thereafter was no good at all.

Since his father was a merchant, it occurred to him that he might become an accountant; and by the time he finished high school he was considered one.

But a few weeks as an apprentice in a dry goods store cured him. He was bored.

“I shall be an engineer,” he announnced grandly.

“How?” asked his father.

“There are schools in Mexico City.”

“Your brother,” Senor Montalbán said, “has a better idea. He is living in Beverly Hills, and he writes that if you want to live with him and go to school in Los Angeles, he will be happy to watch over you.”

“Don’t they teach school in English in Los Angeles?”

“Learn it.”

Ric learned. It took him three months, in the only high school in Southern California which accepted students who did not speak English.

By the time he switched to Fairfax, he was good enough to play the lead in the school production of Tovarich,and that was the beginning.

When his brother went to New York to live, Ric went too, determined to be an actor.

He tramped the streets for weeks. Then, one afternoon, he read of an audition, and applied for it.

The first candidate was a tall, good-looking gentleman, with a barrel chest, who sang two songs in a loud tenor. He was quite good, and there was applause. After him came a statuesque contralto. More applause.

“And now,” said the announcer, “Ricardo Montalbán will sing a Spanish ballad for us.”

no canary he . . .

Ric stood up. “I can’t sing.”

There was a slight pause. “Oh well,” he added, if I could use the mike, maybe—”

He adjusted the mike until it blasted, and eventually started singing “El Rancho Grande.” By this time, everyone was laughing, anyway, and he thought he might as well gag the whole thing.

When he was finished, the agent conducting the audition called him aside.

“You’ll never get anywhere with that face or that voice,” he said, “but you’ve got guts, and a personality. I’ll find a place for you somewhere.” And he did.

An actor in Tallulah Bankhead’s play, Her Cardboard Lover, forgot his lines, and Ric stepped in as the logical replacement. After that, he made some slot machine movies—one of which was called The Latin From Staten Island—and then went back to Mexico, where he made nine pictures, was mentioned for the Mexican Academy Award, and was discovered by Preston Foster.

Whereupon, of course, he came back to Hollywood.

The traffic cop was most understanding. “I’m late for mass,” Ric told him, and the cop, whose name was O’Mara, nodded.

“I’ll just have a look at your license, me boy, and if it’s in order, you may hightail it for the church.”

Ric handed him the cellophane folder from his wallet. The cop examined one side of the license; then, turning the folder over, stared. “Who’s this?”

Flushing, Ric said, “Just a picture of a girl.”

“But she’s only about eleven or twelve.”

“I’ve had it for seven or eight years. I just like to look at it.”

“Well, I can’t give you a ticket for that. Say a Hail Mary for me.”

“That I will,” Ric promised. He was late, all right; all the parking places were gone and he had to leave his car in the alley behind the church. Later, coming out, he saw another motorist had had the same idea. She passed him, and he had a glimpse of flying blonde hair and a lovely almost-familiar face.

Her car was already turning into the street when it came to him who she was. A moment later he careened out of the alley after her. Catching up, he leaned out of his window and said “Hey!” It was all he could think of, and it was not enough.

Georgianna Young, whose picture he had carried for almost eight years, allowed him one icy glare, and disappeared in a cloud of fine California dust.

Two weeks later, Ric ran into Norman Foster. “We haven’t had a decent talk in too long,” Norman said. “Come home with me to dinner.”

“Delighted,” said Ric; unknowingly accepting a date with destiny.

Because Norman Foster’s wife is Sally Blane Foster, and Sally Blane and Loretta Young and Georgianna Young are all sisters.

Wherefore, when Ric stepped through the doorway of Norman’s house an hour later, three beautiful girls walked into the entrance hall to be introduced.

It is not for a Montalbán to be without words for very long.

“Hey,” he said.

“I’m beginning to think you really mean that.” Georgianna grinned. “D’you know, all that Sunday I wondered why you’d chased me. At first, of course, I thought you were just another wolf. Then I remembered what you looked like, and it occurred to me there must have been something wrong with the car, and finally, I got out of the car and went in back and saw what you meant.”

“I beg your pardon?”

“The tail light. Knocked off and hanging down and banging against the fender. That was it, wasn’t it?”

After a moment he said, “But, of course. That was it.”

“What are you two babbling about?” Sally asked. “I thought you didn’t know each other.”

“What a ridiculous notion,” Ric told her. “We’re old friends.” He smiled disarmingly at Georgianna. “Aren’t we?”

She smiled back. “Oddly enough,” she said, “I believe we are.”

And it was shortly after that that Ric told Georgianna how long he had loved her, and how much; and how desperately he needed and wanted her for his wife. That was on the twelfth night after the evening of the dinner party at the Fosters’.

And on the fourteenth day they were married. It was, to be exact, October 26, 1944.

On August 12, 1946, their first child, Laura, was born. Their son, Mark, followed as soon as God and nature would permit. Somehow, this is also typical of Ric: this haste in the great, important things of life as well as in the lesser things. He wants everything, and he wants it immediately.

Robert Hillyer wrote a verse called “Twentieth Century” once, and its lines fit the way Ric is headed for fame and fortune and greatness:

There is no time,

No time,

There is no time—

Not-even for this,

Not even for this rhyme.

THE END

—BY GEORGE BENJAMIN

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE FEBRUARY 1948