Man Power

In every town there are certain men the girls think about—and talk about—whether the men are bachelors, fiancés or devoted husbands. For they have, these dangerous men, that intangible quality of attraction that is spelled s-e-x.

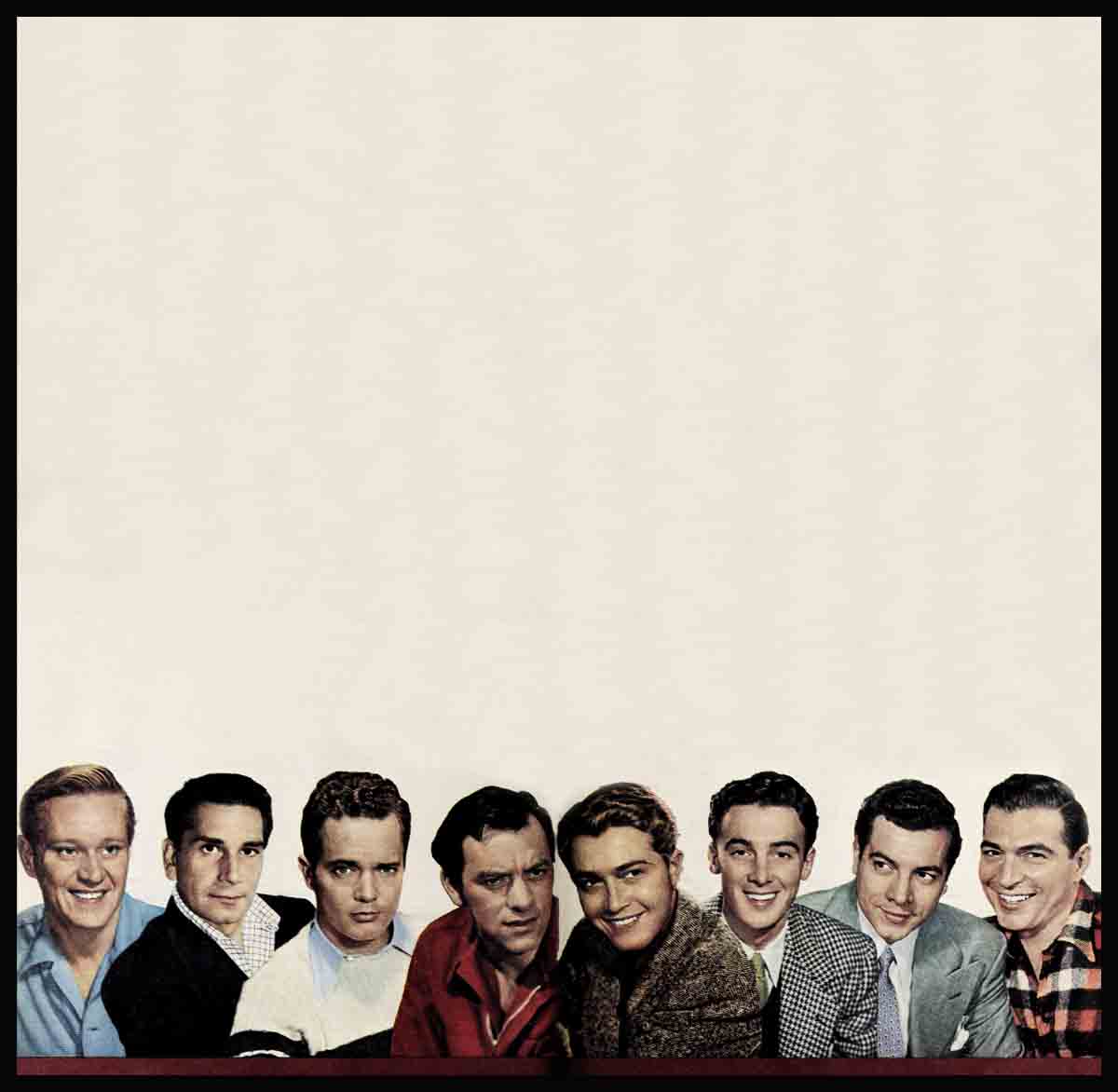

In Hollywood, currently, girl-talk concentrates upon David Brian, Richard Conte, Douglas Dick, John Ireland, Johnny Sands, Jerome Courtland, Mario Lanza and Stephen McNally.

They’re not all young or handsome or, as yet, bright stars. And, with the exception of Douglas, Jerome and Johnny, they’re all happily married.

David’s practically a bridegroom. He and Adrian Booth are devoted, go everywhere together. And everywhere they go, feminine eyes follow. Don’t think Adrian doesn’t know this. But David doesn’t seem to. However, you can’t tell about David. That’s part of his challenge. He has that easy, smiling sophistication that’s born of knowledge and poise, good manners and a nice sense of humor. All this, plus his habit of looking at a woman as if to sat, “You’re quite delightful, really. . . .”

Joan Crawford recognized his attraction the first time she laid her discerning eyes upon him. Whereupon, he was given the crucial role of the political boss in “Flamingo Road” even though he’d never played so much as a bit part on the screen.

Sometimes, it’s difficult to analyze a man’s attraction. But with Richard Conte’s you know at once that his great appeal lies in his strength, mental and physical. Dick’s the quietly confident kind; knows what he wants and goes right after it.

“House of Strangers” marked his first romantic lead at Twentieth Century-Fox. And his love scenes with Susan Hayward, scorching the screen, started a lot more women thinking, and talking.

It wasn’t his looks that put him where he is today. Gene Tierney, his co-star in “Whirlpool,” told director Otto Preminger. “All right. So he’s not handsome. But he looks like a real guy. And that’s not bad.”

Strength in repose: Richard Conte appears next in “Whirlpool”

Alert and attentive: Douglas Dick was in “Home of the Brave”

Dark and dynamic: John Ireland, next in “Cargo to Capetown”

Easy-going ace: Johnny Sands, who will be seen in “Outrage”

Disarmingly different: Jerome Courtland is in “The Palomino”

Direct appeal: Mario Lanza stars next in “Serenade to Suzette”

Masculine magnetism: Stephen McNally of “Woman in Hiding”

Dick’s a Hollywood conversation-piece without being a part of the social scene. He lives quietly with his wife Ruth Strohm. She’s never pursued a career. He thinks she should. And it would be difficult for any woman, even a wife, to resist him.

Then, there’s Douglas Dick, unquestionably one of the town’s most desirable young bachelors, in spite of the fact that he prefers a concert to a premiere and spends much of his spare time writing a play in which there’s an excellent part for a young actor like Douglas Dick.

When he first came to Hollywood, he horrified executives at the Paramount studios by coming to work on a bicycle. Finally, bored with their violent protests, he bought a jeep. In his jeep, to give you some idea of his charm, he carried a scarf so his girl friends, and they are plural, could tie down their hair.

John Ireland, the fourth Hollywood gentleman to intrigue the home-town girls, is described, succinctly, both by Paulette Goddard who played with him in “Anna Lucasta” and Dorothy McGuire who worked with him at La Jolla last summer.

“He has an explosive force,” says Paulette.

“Enormously masculine,” says Dorothy.

Joanne Dru, married to John, might have more to say about the subtleties of his charm. But, when a man’s as intensely masculine as John, that’s sex. For the chemical attraction John received from one of Mother Nature’s overgenerous moments, in itself, is pretty overpowering.

Johnny Sands, with his disarmingly “boy-next-door” way, is another killer. Take that episode of last summer. . . .

A magazine brought a contest winner on a trip to Hollywood. Her Big Moment was a dinner date with Johnny.

He took her to dinner and was very polite, and that was that. But the next day the girl refused to leave town. She was, she said, going to break her engagement to the boy back home, stay in Hollywood, and, she hoped, marry Johnny Sands with whom she had fallen madly in love.

Johnny’s the kind of young man that women like to mother. He has a sweet quality that doesn’t, we hasten to add, detract even remotely from his masculinity. He’s far more interested in other people than most actors. Sensitive, too. Recently, for instance, when he was out with Macdonald Carey, he was embarrassed because the boys and girls waiting outside a restaurant recognized him and not Mac.

Scores of people have sought to label the certain something which sets these men apart. It, the old B.U. (biological urge, to you) high voltage, the get-together principle, whatever you call it, it boils down to good old-fashioned sex appeal. This quality in men or women causes the opposite sex to light up in a way that puts the brightest Neon lights to shame the minute they walk into a room.

This brings us to Elizabeth Taylor’s apt description of Jerome Courtland.

“Something happens when Jerry’s around,” Liz says. since she and Jerry travel in the same young set, she ought to know. “People are gayer, the conversation is brighter . . . I watch, just for fun, as all the girls head his way.”

Jerry comes from the Tennessee hill country. But he’s no hillbilly. Neither is he the sophisticate he might be with his mother something of a socialite. He’s utterly and completely Jerry. Therein lies his charm and, we suspect, the charm of anyone, man or girl, worth talking about.

Jerry drives his studio slightly mad because he takes off on outdoor sport activities without warning. So what if there’s a chance of danger! He drives girls slightly mad, too. Because he takes a girl out two or three times, showers her with attention and then, when she’s convinced she’s the One-and-Only he’s off, with that gay pixie quality of his, on another date.

There are two exceptions to this Courtland rule. Terry Moore, whom he’s dated over and over and over. And Lillian Barclay, the dramatic coach at the Columbia Studios. He returned to study with her when he came home from war. Jerry can be constant enough, she’ll tell you, when anything is really important to him.

There is nothing, nothing, if you ask Kathryn Grayson, even mildly amazing about Mario Lanza’s immediate and sensational success. Kathryn would have been amazed if it had been any other way.

Kathryn doesn’t talk about Mario’s thrilling tenor timbre. It’s her description of the Lanza follow-up with which he holds the girls spellbound at parties.

“Mario,” Kathryn tells the girls, “likes people and goes much more than halfway to meet them. He has the most wonderful way of making you feel that you’re the most important person in the world, and that what you’re saying is the most interesting thing in the world. He’s magnetic. . . .”

Eighth and last comes Stephen McNally, Hollywood’s mystery man. Stephen’s pleasant enough, with the very nicest manners. But don’t pry beyond the complete barrier he maintains between himself and the curious—however beautiful and charming the curious may be. If, Stephen says, it came to a point where he’d have to reveal his personal life or quit pictures, he’d quit pictures. Nobody doubts his word.

He had no notion about playing romantic roles. Neither did his bosses have any notion about casting him in these roles. Leave it to the girls to do it.

“He has the same fascination that Gable has,” Barbara Stanwyck insisted after she worked with him in “The Lady Gambles.” “And he will keep it for a long, long time.”

The studio brass hats remembered what Barbara had said when Stephen’s fan mail recorded, over and over, the same sentiment.

One thing about Stephen that’s no mystery, certainly, is his attraction.

Some men have it. And some, alas, don’t.

Some men know they have it. And some, again but not alas, don’t.

To discover who they are—in Hollywood or any other town—listen to the girls

THE END

—BY NANCY TOWNSEND

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE MARCH 1950