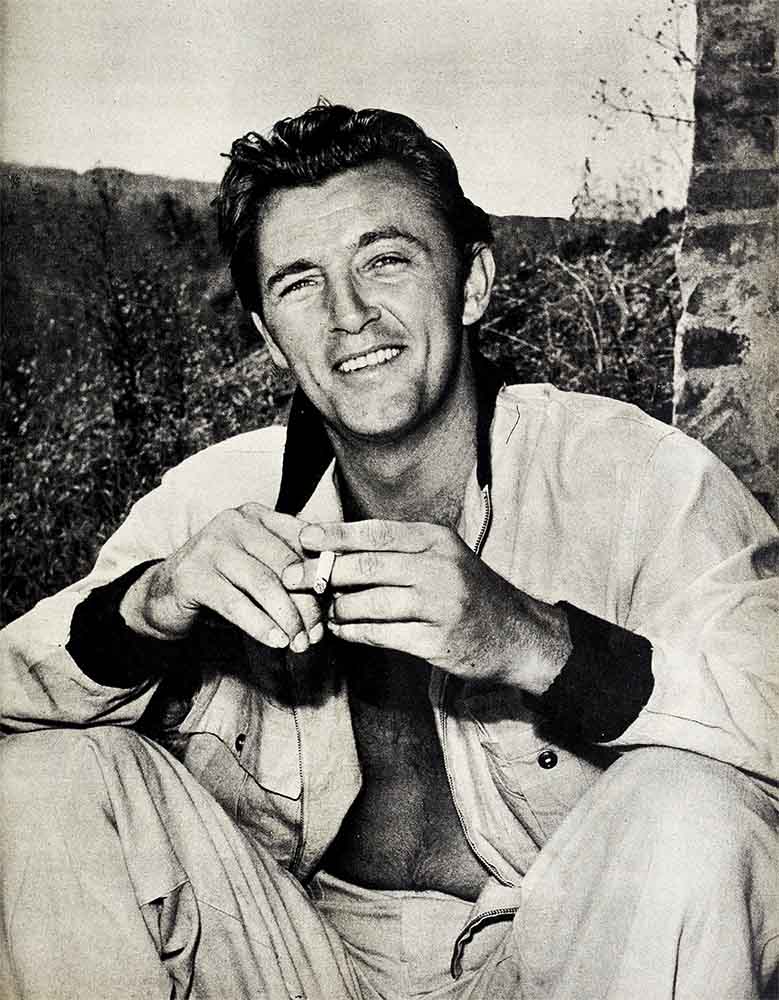

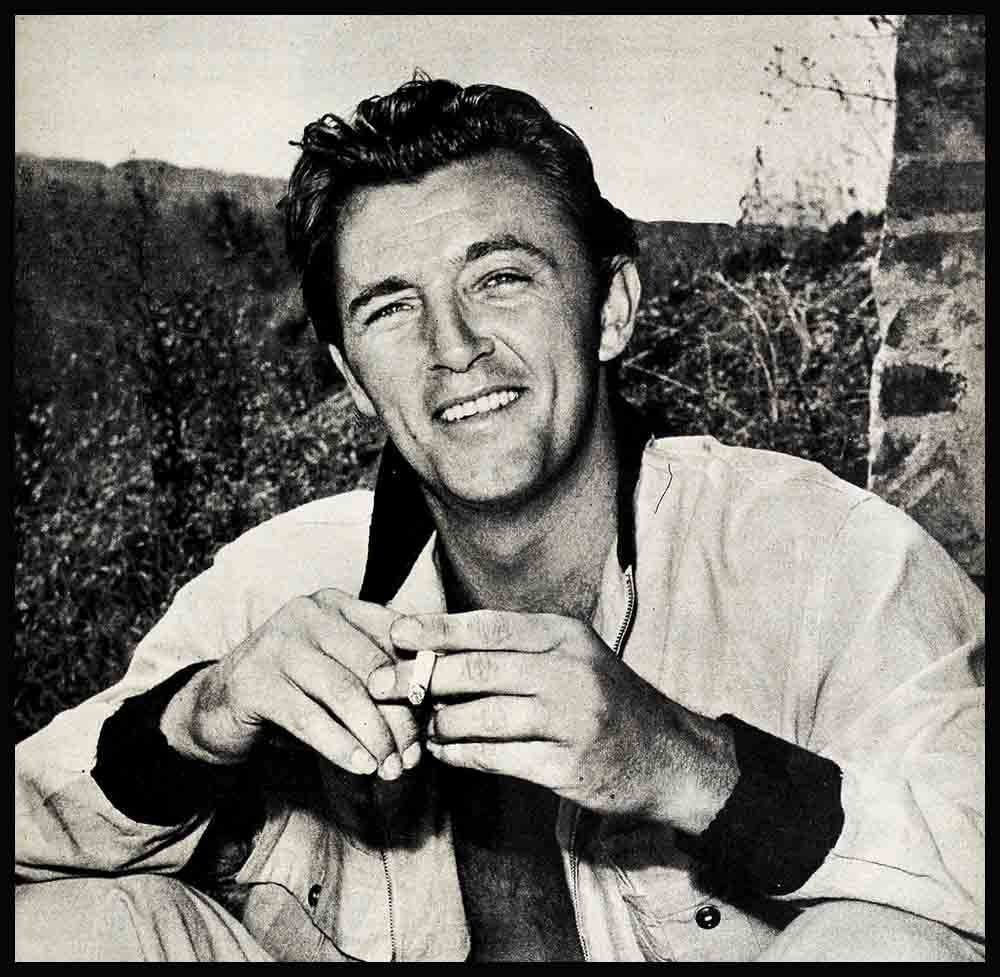

What You Don’t Know About Robert Mitchum?

No considerable feat of memory is required to evoke an incident which happened in Hollywood only a few years ago in which a young actor named Robert Mitchum was sentenced to serve a term in prison after having been convicted on a charge of marijuana smoking. While the press of the country came screaming in for the kill, Mitchum himself accepted his fate with stoic calm, did his stretch at the Wayside Honor Farm near Los Angeles, and returned to pick up the shattered remnants of his career.

Immediately, sibilant whispers were heard in the halls of various studios and on the streets of Beverly Hills: “The guy is through.” “He’s had it!” or “Back to the docks for Mitchum.”

Singularly—and happily—all these poisoned arrows missed their mark by a margin a mile wide. The actor, who still seems largely indifferent to his Hollywood career, continues to saunter with sleepy-eyed nonchalance through a wide variety of roles and to turn in performances which are balm to the troubled hearts of directors.

AUDIO BOOK

So it was with considerable interest that I accepted an invitation to dine with Mitchum and his family at their home in Mandeville Canyon. It was the chance to find out just how this relaxed, go-jump-in-the-river individual comported himself in the midst of that most kindly yet discriminating audience—his own family.

Dorothy Mitchum, a tall, pretty girl whose serious, thoughtful face lights up amazingly in a smile of greeting, led the way into a large library where books, all of which had the friendly look of frequent use, filled one wall. There were large, comfortable chairs scattered about and one huge leather davenport at least eight feet long. A ceiling-high fireplace looked benignly out upon tables piled with magazines, cigarette boxes and plate-size ash trays. It was a room that held out its hand and made you welcome.

Bob had not arrived home yet, and Mrs. Mitchum, apologetically announcing that it was the baby’s supper time, left me alone for a few minutes. Suddenly a miniature Bob Mitchum, about eleven years old, appeared—same wide, sloping shoulders, long upper lip, same candid appraising eyes. “Hello,” he said gravely, “I’m Jim. You’re waiting to see my father?”

I nodded, and noticing a toy airplane he was holding, asked: “You make it?”

He said almost scornfully: “Sure. It isn’t much. I’ve got a better one. Like to see it?”

He left the room and came back, a few moments later, bearing a balsam wood creation that looked as if it might take off into the wild blue yonder at any moment. “It’s got a Wasp motor,” Jim observed, “and when it gets going good it really sets up a howl.”

He began filling a plastic fuel tank with an evil-smelling liquid which, he explained, was a mixture of the highest octane gas and castor oil. “Costs eighty cents a pint,” he said, “but it sure makes a motor talk.”

While he was attaching the wires of a dry-cell battery and twisting the propeller, I remembered a story that Bob had told me about Jim. “There’s a plot of grass and flowers just across the little bridge leading into my place,” he said, “and a neighborhood girl kept riding her pony across it. Jim talked to her about it several times and finally came to me. ‘It’s your problem, Kid,’ I said. ‘You’ll have to figure it out for yourself’

“Well, the next time she showed up with her pony, Jim met her with an air rifle. She didn’t pay any attention to his warning and rode her pony right over the flower patch. Jim took aim and planted a bee-bee shot smack in the pony’s rump. The little animal went into the air, of course, and his rider landed on her little behind. She hasn’t been back since. Jim had taken care of the situation himself. That’s what I think youngsters should always be allowed to do.”

The motor broke into a banshee wail, just as Dorothy Mitchum came back into the room carrying her eight-months-old daughter, Petrine. Frightened at the unearthly noise, the baby began to cry and Jim, with an expression of real concern, shut off the motor. Dorothy smiled. “Thank you, Jim,” she said. “Now we can talk.”

At that moment, a younger boy appeared and stood in the doorway. “This is Chris,” Dorothy said. We shook hands and then both youngsters went in to their supper.

“Chris isn’t like Jim,” Dorothy said thoughtfully. “He was a cuddly, quiet baby. Jim began putting sentences together when he was a year old, but Chris just cooed and smiled. Bob was certain he’d grow up to be an idiot.”

“Either of them want to be an actor?” I asked.

“Jim does. He idolizes his father and tries to be like him in every way. One day when Warner Brothers needed a boy in a picture, they spoke to Bob about Jim, and he said it was all right with him. But as it turned out, Jim was too big for the part and they chose Chris instead. Poor Chris! He was so frightened that he froze solid—couldn’t say a word. Jim was furious. ‘I gave you my part,’ he yelled, ‘and you blew it.’ ”

The telephone rang and Dorothy answered it. It was then almost eight o’clock. “It’s Bob,” she said. “He wants to speak to you.”

“Look,” Bob said placatingly at the other end of the wire, “I got fouled up with a couple of high lamas. Do you know what a high lama is? It’s something that talks in a low, important voice and gives off a sweet odor that smells like money. They want me to do a thing and I’m pretty certain it’s garbage. Tell Jim to put some kindling in the fireplace, pour kerosene on it, then add split logs and pour on more kerosene. I’ll be right home.”

Jim had come back into the library and was twisting the propeller of his airplane again. “Your father wants you to build up a big heat in the fireplace,” I said. “Use plenty of kerosene.”

Jim looked dubious. “Sounds weird to me,” he said. “I know how to build a fire, but I’ll do it just like he ordered.”

When Bob came in the fire was leaping high. He went straight to his wife and kissed her gently. “I’m sorry, honey, but they got me in a corner. I fought my way out and here I am.”

“So is your guest,” she reminded him.

Swinging around, he held out his hand. “Too bad you had to wait. Hope you weren’t bored.”

“Anything but!”

He laughed. “Okay, now we’ll talk. Scram, you guys,” he added quietly to Jim and Chris.

Jim was still violently manipulating the propeller of the airplane. “It won’t start,” he lamented. “You know, Dad, this thing ought to have some kind of gadget that’ll wind it up fast. Like a regular ship.”

Mitchum got down on the floor and took the model plane in his hands. “Duck soup,” he said. “We’ll get a small electric drill with a ratchet attached. Remind me tomorrow. Now would you disappear?”

As the boys left, Mitchum said thoughtfully, “He’s quite a guy, that Jim. The boys at the military school made it a little rough for him at first on account of me. You can understand why. But he took it in stride and now he’s one of the gang. It takes character to ride through a deal like that.”

We began talking about Bob’s career (a word he objects to strongly). “Just now I find myself a leading man,” he said. “It’s most embarrassing. Tomorrow I might be out of Hollywood on my ear. Well, I made a living as a dock-hand once and I could do it again and be quite happy.”

He is constantly beset by a feeling of insecurity, despite his salary of $5,000 a week. Up to the time of his last raise to this impressive figure, he would insist with complete gravity that he has never been really solvent in his life. Things happen to him. once his business manager, a trusted friend, vanished with all his savings. Not long ago he bought an expensive automobile, and a garage hand, driving it to California from Texas, where Bob had been vacationing, put the wrong kind of oil in the crankcase and ruined the engine. “I’ll never have any dough,” Bob States with conviction. “I get conned out of it. I’m always meeting guys I knew when I was on the bum as a kid, and they’re in trouble. But not so much trouble that ready cash won’t solve the problem. I’m a push-over because I remember the swell Joes who were good to me in the jungle camp days.”

One senses that he often goes back in his thoughts to those free, irresponsible days with at least a small feeling of nostalgia. He likes to talk about the nights when he slept on the grass beside a softly-flowing river in the south, with the moon coming up over a tamarack swamp and a loon crying dementedly somewhere in the distance. He recalls the good mulligan stews they used to make in a kerosene tin while a buddy sang nostalgic songs.

Now thirty-five years old, six-feet-two and erect as a Marine sergeant, Mitchum is what they used to call “a fine figger of a man.” His thick, coarse hair, the color of faded wheat straw, falls over a high, rather fine forehead. His face is long and faintly sullen. He walks with complete grace and a truculent roll of the shoulders. It was this walk of his which first drew the attention of William Wellman, the director. “I had never seen an actor move with such perfect rhythm,” he says, “so I called him over to the studio and gave him a test. It was a page or two of dialogue from the script of ‘The Story Of G.I. Joe,’ and I stood him up beside the wheel of a broken gun carriage and told him to sound off. He turned in a performance that would shake your heart. Of course, he was hungry then, broke and needing a job. Hungry actors are generally good actors.”

Henry Hathaway, who is directing Mitchum in his latest picture, “White Witch Doctor,” confirms Wellman’s high opinion of Bob’s histrionic abilities. “He is one of the few actors I know who can turn in an almost perfect performance on the first take,” he says.

The economic conditions under which Mitchum grew up seem to have alternated between “dangerous” and “desperate.” With the death of his father, when Bob was eighteen months old, his mother went to work on a newspaper, later marrying the feature editor. The boy spent his time on the streets of Bridgeport, Connecticut, completely without supervision of any kind. In 1927, he ran away to Long Beach, California, where his married sister, Julie, was actively engaged in a small, experimental theatre movement.

After numerous jobs, ranging from acting in the Long Beach Civic Theater to common labor, he returned to the east where, a few years later, he married his boyhood sweetheart, Dorothy Spence of Dover, Delaware. The young couple then came back to California and Bob found employment in an airplane factory. This precarious existence endured until Harry Sherman, prodigious maker of Western movies, gave him a small part in one of his pictures. That night he rushed home to the bleak flat where he and his young wife were living, shouting wildly that their future was assured. After that, there ensued a succession of Westerns, culminating at last in “Thirty Seconds over Tokyo,” which he regards as one of his best pictures. His more recent films include “The Lusty Men,” “Angel Face,” and “White Witch Doctor.”

The hour was late and it was time to go. Mrs. Mitchum appeared in the doorway and beckoned. “I want to show you something,” she said, and led the way into a bedroom where Jim and Chris were fast asleep—with plastic space helmets completely enclosing their tousled heads.

Bob grinned. “Look at the little monsters,” he said. “They’re probably halfway to the moon by now.”

There was something in his voice, a quality his audiences do not know. Tough guy, eh? So this was the hard character who has battered his way up from jungle camps under railroad bridges to a high-salared position as one of Hollywood’s most controversial figures. There was nothing ruthless, no harshness in his face then. A remark he had made earlier in the evening came back. “It’s been rough sometimes,” he said, “but I’ve enjoyed every bit of it.”

But there had been no moment in his life, that was clear, that had ever equaled this one in that quiet room with his wife as they stood looking down on the sleeping forms of their two sons.

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE APRIL 1953

AUDIO BOOK