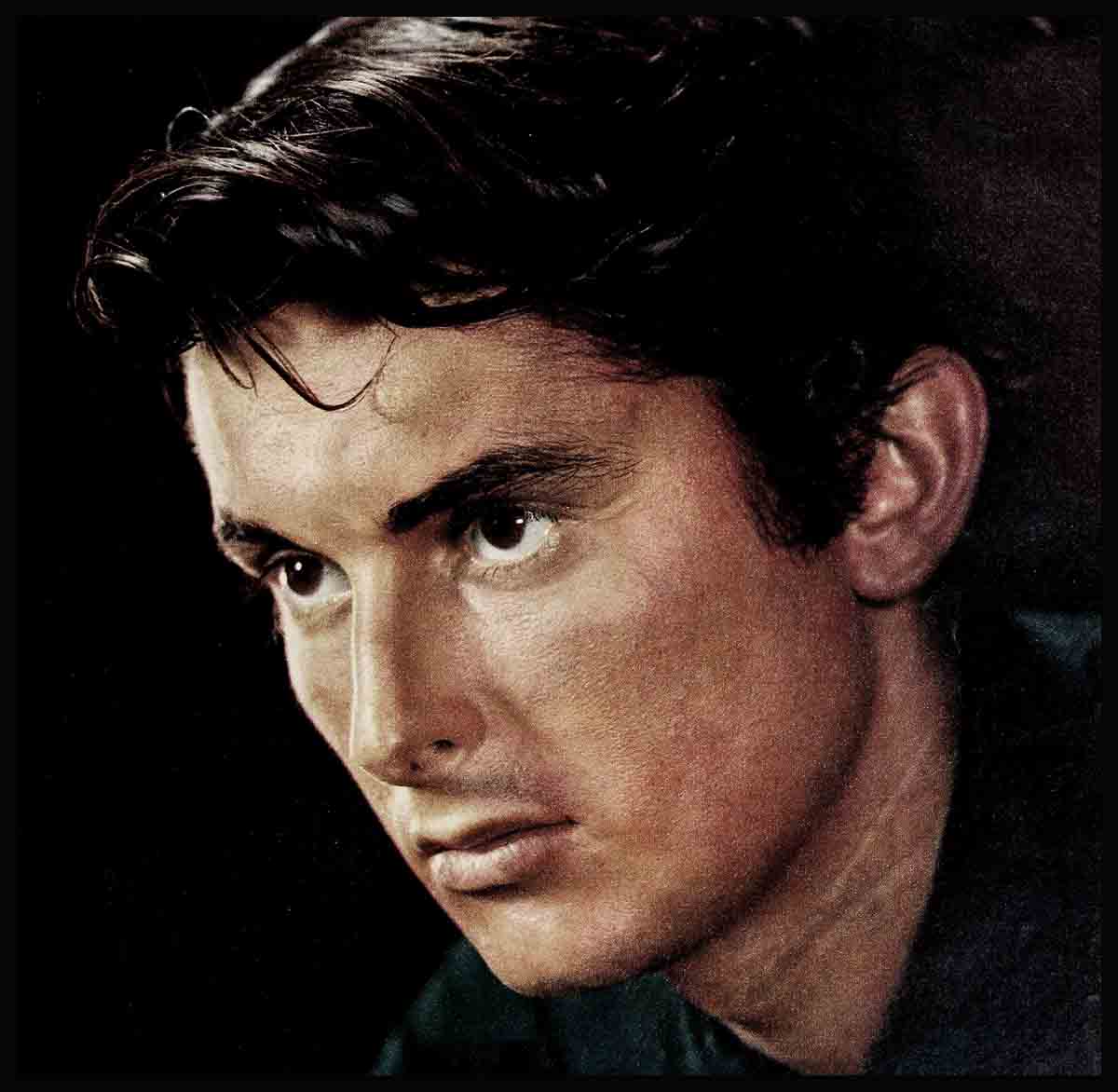

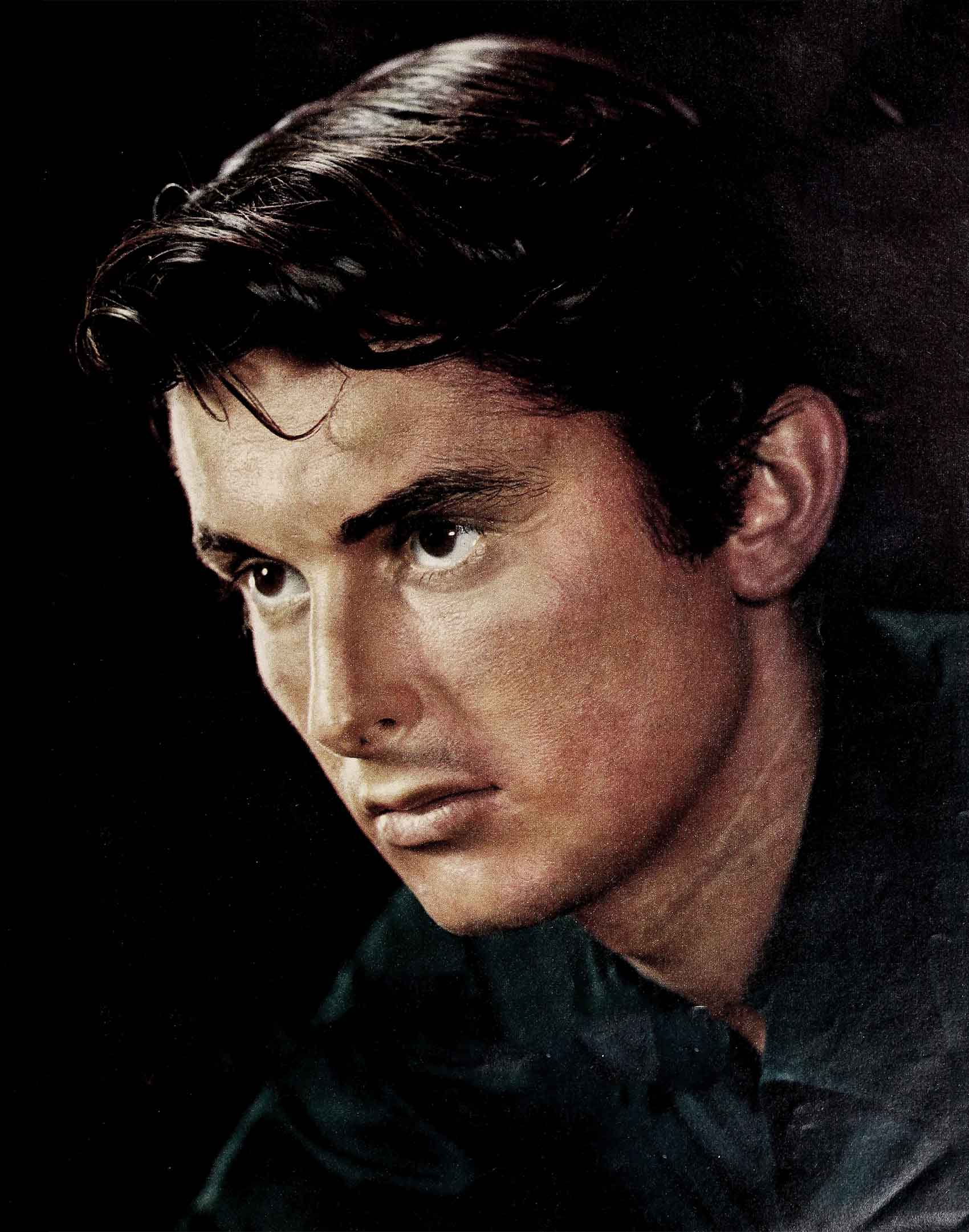

Robert Evans: “I’ll Never Fall In Love Again”

When she walked into the cocktail party that night a few years ago, back when Bob Evans worked as a cloak-and-suit salesman on New York’s Seventh Avenue before he became a Hollywood star—Bob had been about to leave. Instead, he put down his coat and went back over to the corner where he’d been standing for the last hour alone. He had been getting bored with all these drinking, chattering people he barely knew. But now he stood there—still alone—so he could watch her, this girl who’d just come in.

She fascinated him and she puzzled him.

She fascinated him because she was so darn pretty and sweet-looking and, though she was a blonde—and maybe even a dyed blonde, she was nothing like the hard, breezy girls he’d been meeting and then avoiding at the few parties he’d gone to in the past five or six weeks.

Yet she puzzled him, too. Because sweet as she looked, she’d arrived with two very dapper-looking men, not too young—in fact not young at all.

Bob stood there, holding a drink he wasn’t really drinking and lighting a cigarette he barely puffed at from time to time. He nodded vaguely at people who stared his way now and then—but kept watching her.

And his fascination grew. Finally, after what must have been half an hour, when for a moment she was alone, he walked over to her and said, “Excuse me, but I’m Robert Evans. And I’ve been watching you.”

Bob had expected her to say Oh, really? or Why? Is there a smudge on my face? or Do you think you saw me in Cannes, maybe, last Spring? or any of a hundred empty nothings a girl who came to this type of New York cocktail party might ordinarily have said.

But instead the girl looked him in the eye and, frankly said, “I know. Because I’ve been watching you, too.”

“I didn’t notice,” Bob said.

“That’s good,” the girl replied. “My sex has to be careful about being too obvious when it comes to things like that.”

Bob smiled.

So did the girl.

And anybody else who might have been standing around at that point, watching them as they’d been watching each other, could have told you that the most beautiful and important chemicals in the world were beginning to brew up a storm right now between these two—a very subtle, complicated, crazy, wonderful, exasperating, incomprehensible kind of storm that is commonly known as love.

The meeting took place five or six years ago and we don’t know too much about this girl today. As Bob told us recently, “I can’t tell you her name. I wouldn’t want to do that. But she’s an actress. And you’ve probably seen her a few times, though she hasn’t been doing very much work lately.”

His mother’s view

In an interview a couple of days later his mother said, “She was a fine girl and very talented and we all wished her well in her career. For a time, when it looked as if everything was serious with her and Bob, we wished them well, too, even though she was of a different religious faith.”

Said a friend of Bob’s, “I liked her because Bob did. But I could never get over the feeling that no good would ever come of this match. She was a swell girl in many ways. She was smart and she was good-natured ‘and she was fun. But like lots of girls who want to become actresses, she was aS aggressive as a Russian in Budapest. She didn’t show it much. But she showed it at times. And this I didn’t like.

At the time they met, Bob was as ready to fall in love as any man has ever been. Unfortunately, as we will see, he fell too hard.

Why was he so ready? Simple. He’d been very sick for the last couple of years and he’d undergone a slow recuperation and at a time other fellows his age were going out on dates and flings, Bob had been getting to bed at nine and nine-thirty every night. As he now jokes about this period, “You can dream about girls that way, but you sure don’t get to meet them!”

Joking aside, though, the illness was a bad one and it nearly cost Bob his life.

“It came suddenly,” his mother says. “Bobby and his father and I were driving down to Florida for a three-week vacation. We were in a little town, a little more than halfway there, when he began to complain about a pain in his chest. We rushed him to a local doctor. The doctor examined him and smiled and said there was nothing to worry about, that Bobby had a case of indigestion. He gave us some pills: and said everything would be all cleared up by the time we got to Florida.

“But when we got there, Bobby’s condition was worse. We took him up to the hotel room first, thinking that maybe if he lay down for a while he’d feel better. But after a very little while we could see this was no good. Thank God there was a hospital right across the street from the hotel. We took Bobby there. A doctor examined him while we waited in an office next door. I thought the examination would never end. Finally, the doctor came out. He asked us to stay seated and be calm while he told us what was wrong. He said that one of Bobby’s lungs had collapsed, that it was pushing against his heart—and that Bobby would be dead in another couple of hours if he wasn’t taken care of right away.

“Bobby’s father and I stayed up all that night, right there in the office. We prayed. And the next morning when the doctor came back in and told us that our boy had pulled through the crisis, that he’d have to stay in the hospital a couple of months and rest for at least a year after that, we were so glad he was going to live and we weren’t going to lose him, that we couldn’t do anything else but take each other’s hands and cry.”

So ends Bob Evans’ medical history.

And it had lots to do with his later, romantic history.

Especially the night at the crowded New York cocktail party when he met the first girl he’d fallen for since his teens—this very pretty, sweet-faced blonde, this girl he’d first seen only a little while earlier and had suddenly wanted so much to get to know.

That night was wonderful

They left the party and had dinner together. The girl explained that the two men she’d arrived with were theatrical agents who were so drunk that they could hardly remember each other, let alone her.

Dinner that night was wonderful.

The girl told Bob about herself: that she wanted more than anything in the world to be an actress; that things seemed to be moving along pretty well; that she expected she might be in Hollywood and in pictures by the end of a year or two.

Then Bob told her something about himself. He’d been an actor once, way back—when he was eleven, “Here I was, just a kid,” he said, “with this ambition to perform burning inside me. Even at that age, though, I knew the theater was tough to crack. But our family used to listen to the radio a lot. And one day I realized there were lots of stories being told on the radio and that more than one of them had parts for boys about my age. So the next day I got on the subway and went to downtown New York, to CBS. By luck I got to see a director and I guess he liked the way I talked, the tone of my voice, because he said, ‘Okay, young man, we can use you.’ I remember it was later that day when Eleanor Kilgallen, Dorothy Kilgallen’s sister, was signing me up, that she looked at me and said, ‘This is the sorriest move you could make, my boy. You know, it’s not going to be an easy life after this.’ ”

“It might not have been easy,” Bob went on. “But it sure was fun.” He continued with the kid radio stuff for a few years, then stopped a while, and again went back to radio in Florida where, for about a year, he worked as the youngest disc-jockey in the state.

“But now that’s all behind me, I think,” Bob told her. “A little while back, when I was recuperating, I decided maybe acting wasn’t for me. So I came to New York again to get a job, a steady job. I thought I’d like to get into the garment business. Nobody would hire me at first. They didn’t think anybody with an acting background was stable enough. But finally this one place said they’d give me a try. They took me on as a messenger boy for forty-five whole dollars a week. Right after work, I’d go to school for a course in marketing and selling. I figured that in this business it’s important to know what adjectives to use—because if you don’t use the right ones at the right time, you might as well give up.”

He ordered another cup of coffee for himself and the girl as he went on.

Bob continues his story

“The study paid off,” he said. “I was a salesman in less than a year. And now, well, my brother, Charles, and Joe Picone, a friend, have started their own business in women’s sportswear—it’s called Evan-Picone—and they’ve invited me to join them as a partner. It’s not a big business yet, but I think someday it will be, and. . . .”

The young man who was soon to become a millionaire through this very business, stopped now and shrugged. “Well, I guess you’ve heard enough about me for one night,” he said.

“Why?” the girl asked, stirring her coffee but not looking down at it. “Will there be other nights?”

“There could be tomorrow night,” Bob said.

“There could.” She looked at him, very seriously for a moment.

And then she burst into a big, happy smile.

“I’ll be ready at six-thirty,” she said. “Or six, if that’s not too early for you.”

Bob made it at five to six that next night, secretly glad that he would be able to see this girl for five minutes more than the fates of time-arranging had planned.

And the girl was glad, too. After their first meeting, she’d thought about Bob all that night—as she was to tell him later—and all that morning and afternoon. And now he was there and they were going out on a date and there’d be no stopping the great time they would have that night.

And it wasn’t many dates later that they both stopped long enough to tell each other they were in love and that there were no two luckier people in the whole wide world than they.

Two of the nicest

Their love lasted for two happy years.

“They were probably the most in-love young couple I’ve ever seen,” a friend of Bob’s has said. “And why shouldn’t they have been? They were two of the most attractive young people in New York. They were two of the nicest. Her career was beginning to do better and better. And on Bob’s side, Evan-Picone was becoming what it is today—one of the finest and most successful women’s fashion houses in the world. Yes, things were really going great guns and there was talk of marriage.

“And then came a little phone call from Hollywood and it was like a love story in a magazine where the type-setters had made a mistake and suddenly it became a different story. Because the love element wasn’t there any more—at least, not on the part of one of them.”

The phone call, of course, was for the girl. It was from a producer who was offering her a part in a picture. The picture, he said, was due to roll within a couple of weeks and she would have to come out to the Coast, pronto.

The good-byes between Bob and his girl had to be brief. But somewhere along the line—at the airport, in fact—the girl made Bob promise that he’d be out to California to see her.

“It won’t be easy re-arranging the business schedule,” Bob said. “And you won’t be out there very long, anyway. And—”

The girl interrupted him, frantically. “But you will be out, won’t you?” she asked. “Please?”

It made Bob feel very good to know that this girl loved him this much, so much.

“Yes,” he said, nodding, “I’ll be out in a couple of weeks, just as soon as I can get away.”

Then he kissed her long and hard.

And he watched her as she rushed off to board the plane for that fabulous town in the West that has a tendency to change most people who come in contact with it—some for the better, some for the worse. . . .

It was a few weeks later when Bob phoned his girl from New York. “Everything’s set,” he said. “I’m leaving on a morning flight tomorrow and I’ll see you for dinner.”

The girl sounded overjoyed. She explained that production on the picture was being held up for a while and so they’d have at least a week together, just the two of them.

“Hurry darling,” she said, as if she were about to break down and cry. “Hurry.”

And that was all Bob needed.

“I love you. I love you. . . .” he said over and over, till the operator interrupted and told him his time was up. “I love you,” he said once again before hanging up, meaning those words as he never knew they could be meant before. . . .

Then in Hollywood . . .

When Bob got to the Hollywood hotel where his girl was staying, he knocked on her door and then looked down at his watch.

It was exactly five minutes to six.

He smiled. This was a very setimental hour in his book, and it seemed to him to be one of those perfect coincidences that could only lead to more perfect things.

When the girl opened the door, she was in her robe.

“Oh, Bob!” she said, looking terribly confused. “I’d almost forgotten you were coming!”

And if ever a heart has dropped, low, to the pit of the stomach, Bob’s did then.

“Bobby,” she said, after kissing him quickly and leading him into the room, “last night I got a call from the studio. They want me to go to Boston for about a week to do some public appearances for them.”

“When do you have to go?” Bob asked.

“Tonight,” the girl said.

At that moment, the telephone rang.

“Oh, hello,” she said, beginning to laugh. “Yes, isn’t it marvelous? Not that Boston is New York or Chicago, but I’ll be doing publicity work before I’ve ever even been in a picture!”

She shot a quick glance over at a stunned Bob and indicated to him that she’d be off the phone in a minute.

“Yes, yes,’ she continued, “and I spent all day buying some new dresses and getting a hat and bag and. . . .”

She went on, for lots more than a minute.

And when she hung up, she barely had time to explain things to Bob. “It all happened so quickly,” she said. “And I meant to phone you back last night, but then I forgot—”

“You forgot?”

“Well, I kind of put it off and then I got sleepy and—well, yes, I forgot,” she admitted.

In this business . . .

Bob stared at her as she talked. It was as if, after two years, he were looking at another girl. Her voice sounded different—shrill, tense, excited. And her face while still pretty was different too. Her eyes, especiallyher eyes, were different—the softness in them Bob had loved so much was suddenly gone—all the warmth gone, all the love gone.

“I had thought that maybe you could fly back East with me tonight—that is, if you wanted to,” the girl went on, “but then you’re probably tired and would like to hang around here for a few days.”

“Sure,” Bob said. “Sure.”

The girl patted him on the cheek. “I hope you’re not hurt, darling,” she said, this different voice spewing out the string of quick sympathy. “But if a girl’s going to get anywhere in this business, she’s got to go where they tell her.”

With that she rushed into the bedroom to change.

And in less than an hour she was gone. . . .

“It took me a long time to get over that,” Bob said the other day, “but after a while you get over anything, I guess, especially something that you learn probably wasn’t worth having anyway. And still, though I got over it, it left me with the feeling that I would never fall in love again. . . . I still have this feeling.”

Bob paused as if he were thinking about another trip he made to Hollywood a couple of years later, the business trip on which he was discovered by Norma Shearer and given a part in Man of a Thousand Faces, a bigger part next in The Sun Also Rises, and most recently the big hunk of part in a picture that is already, months before its release, being called a Western Classic by the inside movie crowd, Quick Draw.

“I guess I feel I may never fall in love again because, honestly, I don’t seem to meet many girls,” he went on. “Oh sure, I’m out in Hollywood, the business being what it is, I see a lot of glamor-type girls and date them from time to time. And when I’m in New York, at the office, there are models around all the time, beautiful girls, very beautiful girls. But, I don’t know—for some reason I can’t seem to get too worked up over them. I guess what I really want is a girl who’s not in these professions and in a position like mine. It’s hard to meet this kind of girl.

“So what do I do? Well, I turn down approximately one party invitation a night, maybe going to one a week. Maybe one or two other nights a week I’ll go to a nightclub or to the theater. But the rest of the nights I go home and I just stay put. I have a big apartment in New York—a beauty, overlooking the East River. And on the quiet nights I make a bite to eat and sit around and read.

Again he paused. And then he asked, “It all sounds kind of sad, doesn’t it? Well, I don’t know if it’s sad or not. But that’s the way it is. Sure, maybe someday I’ll be at the right place at the right time and the right girl will happen to walk into the room and I’ll take a look at her and I’ll know. But then again, maybe that time will never be. So if sad’s the word you want—well then yes, it is sad.”

As Bob was speaking this time, of that right girl just happening to walk in, we couldn’t help thinking of another girl—a pretty, sweet-faced blonde, who’d walked into a certain room on a certain night a few years back.

And we couldn’t help but wonder if maybe she—this girl who was going to become a big movie star and who gave the heave to a very nice guy who’s on his way now to becoming a really big movie star—if maybe she feels things worked out pretty sad, too.

THE END

Look for Bob in 20th-Fox’s QUICK DRAW.

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE SEPTEMBER 1958