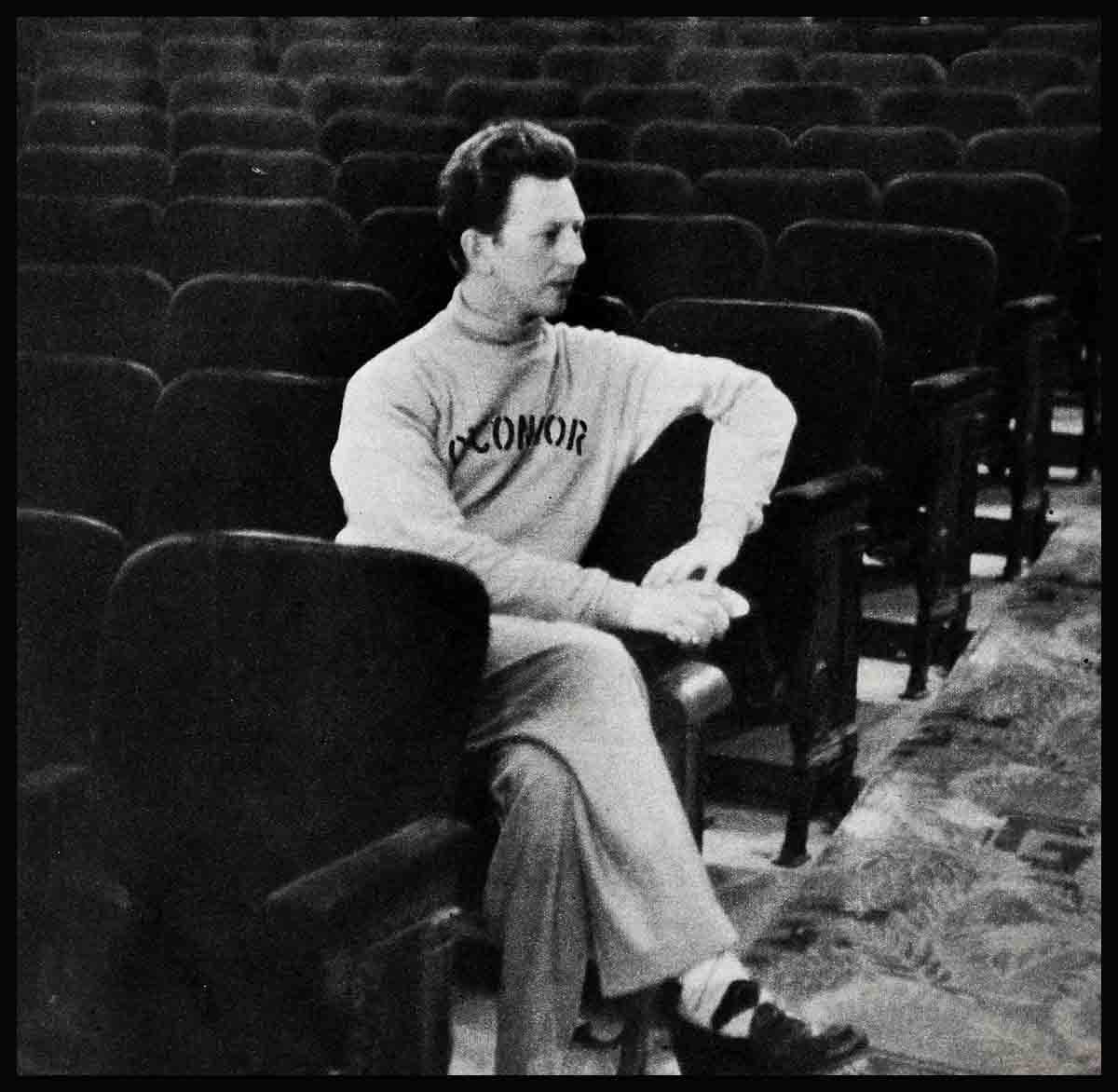

Too Busy For The Blues—Donald O’Connor

At twenty-seven, Donald O’Connor has made four comebacks in showbusiness. He speaks of the fact with a tinge of wonder that he could have been so fortunate. Yet the great majority of entertainers are lucky if they have made, at twenty-seven, the first step on the ladder to success.

It is part of Donald’s charm that he minimizes, both to others and to himself, the peak he has reached. His sporadic appearances on television’s Comedy Hour in the last two years have built him from one of the lesser lights in the world of showbusiness to one of the top five entertainers in America today. The talent has been with Donald all his life, but not until the advent of television did he have an opportunity to display to so many people the fact that he can sing, dance, clown—and think—with the best of them. His fan mail has soared to phenomenal quantities, and some have said that the young Mr. O’Connor’s performances are second only to the “I Love Lucy” show in the hearts of the nation.

Donald himself says, “I’m just starting to go places.” This statement doesn’t stem from any urge for power and glory; rather it indicates that he himself doesn’t realize he is at the top.

Like all comedians, he is expected to be a funny man in his personal as well as his professional life, and it comes as a pleasant surprise to people meeting him for the first time to find that Donald is actually rather shy, a modest young man who seems uncomfortable in the glare of the public spotlight. His conversation tends to be on the serious side, and the

humor that creeps into it is quiet and delightfully subtle. He holds up amazingly well under the continual pressure exerted on him by his busy schedule. But although the famed O’Connor energy is still there, he appears to be trying to hide the fact that he is, underneath the facade of the successful entertainer, an extremely tired young man.

It is small wonder. In the past year he has made three movies (the average for an established Hollywood actor); he has formed a music publishing company with his sidekick, Sidney Miller; he has contracted to make recordings for Decca, and approximately every five weeks he has starred on the Comedy Hour, a stint requiring a grueling month of rehearsals for each show.

On top of this, his personal life is in a turmoil, resulting from a separation from his wife. It is not the first time Gwen and Donald O’Connor have gone their separate ways. The nine-year-old marriage has survived several temporary rifts, some of them lasting only a week, others stretching into a month.

Neither Gwen nor Donald will discuss their troubles, and the consensus of opinion seems to be that while the two are still in love, their temperaments are such that they cannot live together peacefully.

Many comedies have been written for both stage and motion pictures that revolve around a married couple who worship each other yet are scrapping perpetually. It can be funny in a play or a film. But it is far from amusing when it happens in real life. Donald and Gwen have suffered a lot of heartaches. Their first serious quarrel came in the spring of 1948 when they had been married four years; another followed in the fall of that same year. The year 1950 saw another rift, and 1952 began a series of spats. Each successive separation took a little longer to mend, and it can be assumed that while their earlier reconciliations were made possible by the resiliency of their extreme youth, the more recent rhubarbs are a much greater strain on both. Possibly they are beginning to look on their troubles with more maturity and are trying to find a middle road that will make their marriage more secure.

As this is being written they have been separated more than three months, making the most serious rift thus far, but it is the hope of everyone that rumors pointing to another reconciliation may be true. Both are well liked by all of Hollywood, and both have mutual friends rooting for a permanent reunion.

Donald himself will make no statement concerning the situation, and the reason for his silence is a thoughful one. “This is a business that is built on sensationalism, and it’s also one in which the performers are looked up to by the young kids in America. For some reason, they tend to pattern themselves after their favorite entertainers, so a guy in my position has a lot of responsibility. I can’t make a statement about my marriage because I myself don’t know how. things will work out. If and when the situation has settled down and cleared, then I’ll have something to say. I’m not an impulsive guy—I don’t go around saying one thing one week and something else the next. When I know what the score is, I’ll let other people know. Until then, the most sensible and logical thing to do is to keep quiet about it. That’s the least I can do for kids who might be so affected that they’d get the idea that it’s smart to split up a marriage. It isn’t. Nobody knows that better than I do.”

Donald has often been referred to as an example of the typical American youth. (“I don’t get it,” he says. “The average American boy is six feet tall, and look at me.”) And this is undoubtedly the reason he feels so strongly that any personal acts of his own might influence others. His consideration of his responsibility under the circumstances is remarkable, and rare. A great many people in Hollywood conduct themselves like lunatics on a binge in a monkey house, with neither a thought nor a care for the impression they are giving the youngsters who have regarded them as heroes and heroines. It’s fair to say, however, that most of these are people who came to success in movies later in life. Those who grew up backstage, such as Donald, feel a greater debt to their fans.

O’Connor’s whole life has been influenced by show business and its responsibilities, and he feels he is lucky because of it. “I grew up learning a trade, and I learned it from the bottom up. It became natural to me, so that today going into a dance is a part of me, like one of my toes. When you grow up with a career, you build not only your stage personality, but your own true personality is affected by it every step of the way.”

A lot of bitterness and heartbreak have gone along with his remarkable career. As a child he spent both the light and dark hours on stages of countless theatres, both drab and elegant, contributing his bit to the family’s vaudeville act. Success seemed to come when at twelve he was signed by Paramount Studios to appear as a child actor in “Sing You Sinners” with Bing Crosby. He made many movies there, and one at Warner Brothers, but like all child actors, he eventually reached an age where there were no parts for him. He went back to vaudeville with the family, and then his brother Billy died, and Donald stayed with the act.

In 1942, when he was sixteen, he made a new start in movies, and once again the spotlight pointed him out as an important find for the screen. In two years at Universal Studios he became a headliner whose future promised great things. He had fallen in love with Gwen Carter and despite the fact she was only seventeen and he eighteen, he began thinking seriously of marriage. It was decided for him when the United States Army invited his membership. He and Gwen were married, and that same night he left for his designated camp.

Two years later he climbed into civilian clothes once more, and trotted happily to his home lot, Universal. At the time, Universal was merging with International Pictures, and no one at the studio was quite sure of future plans. One thing they were sure of—they didn’t know what to do with Donald O’Connor. His fame had held fairly well, inasmuch as he had slaved through eleven movies in the last year before he went into the Army, and the last film of that batch was still showing at the time of his release. However, new faces had come onto the scene while Donald was doing his stint, like so many returning actors, he found it impossible to pick up where he had left off. The studio paid him his contract salary but had no work for him, and so Donald took off on a series of personal appearance tours. He did this for two reasons. The first was that he is a born trouper and can’t stand idleness. Show business is in his blood and to Donald, no bookings mean no contentment. The other reason was financial, He not only had a wife to support, but a ew baby daughter, and his salary as Pvt. O’Connor hadn’t added up to exactly a lush existence for the family.

It was his first experience with big money in two years—the salary from the studio and the income from the tours, and Donald threw money to the four winds. He bought a house, he bought automobiles, he took his wife to a fur shop and his mother to a jewelry store. He lavished gifts on everyone and the following March was stunned by a staggering tax bill from Uncle Sam. He just didn’t have the money, and for a while it seemed he might have to sell the house, the first and only home he and Gwen ever had together. The situation was saved by the trust fund into which had gone fifty per cent of his earnings as a child actor. The taxes were finally paid and Donald put himself on a flat allowance of fifty dollars a week for spending money, a figure he hasn’t changed despite the recent boom in his career.

During that first year out of the Army he lost some self-confidence. He still had talent, but if the studio didn’t seem to want to put him to work, it left him without direction and with considerable, understandable bitterness. “Francis,” the movie about a talking mule, changed all that. The picture was immensely popular and put Donald solidly back on the silver screens of the world. It grossed tremendous profits and the studio, now consolidated and ready for planning, went ahead with a batch of sequels to the first “Francis” movie. The latest is “Francis Covers the Big Town.” Donald became so closely associated with the pictures that strangers frequently addressed him as Francis.

But like all sequels they gradually dwindled in quality, and Donald was beginning to wonder if he and the mule would be making movies together twenty years hence, when Jimmy Durante asked Universal-International if Donald could appear on his Comedy Hour show. The timing was perfect. Donald’s bit on the program was such an immediate hit that the sponsors began negotiations to give O’Connor his own show. He not only got it, but the new surge of his popularity opened the eyes of movie producers at other studios. He was loaned to Twentieth Century-Fox for “Call Me Madam” and to M-G-M for “Singin’ in the Rain” and “I Love Melvin.” At U-I he did “Walking My Baby Back Home.” This fall he will make “White Christmas” at Paramount, re-joining Bing in a movie after fourteen years.

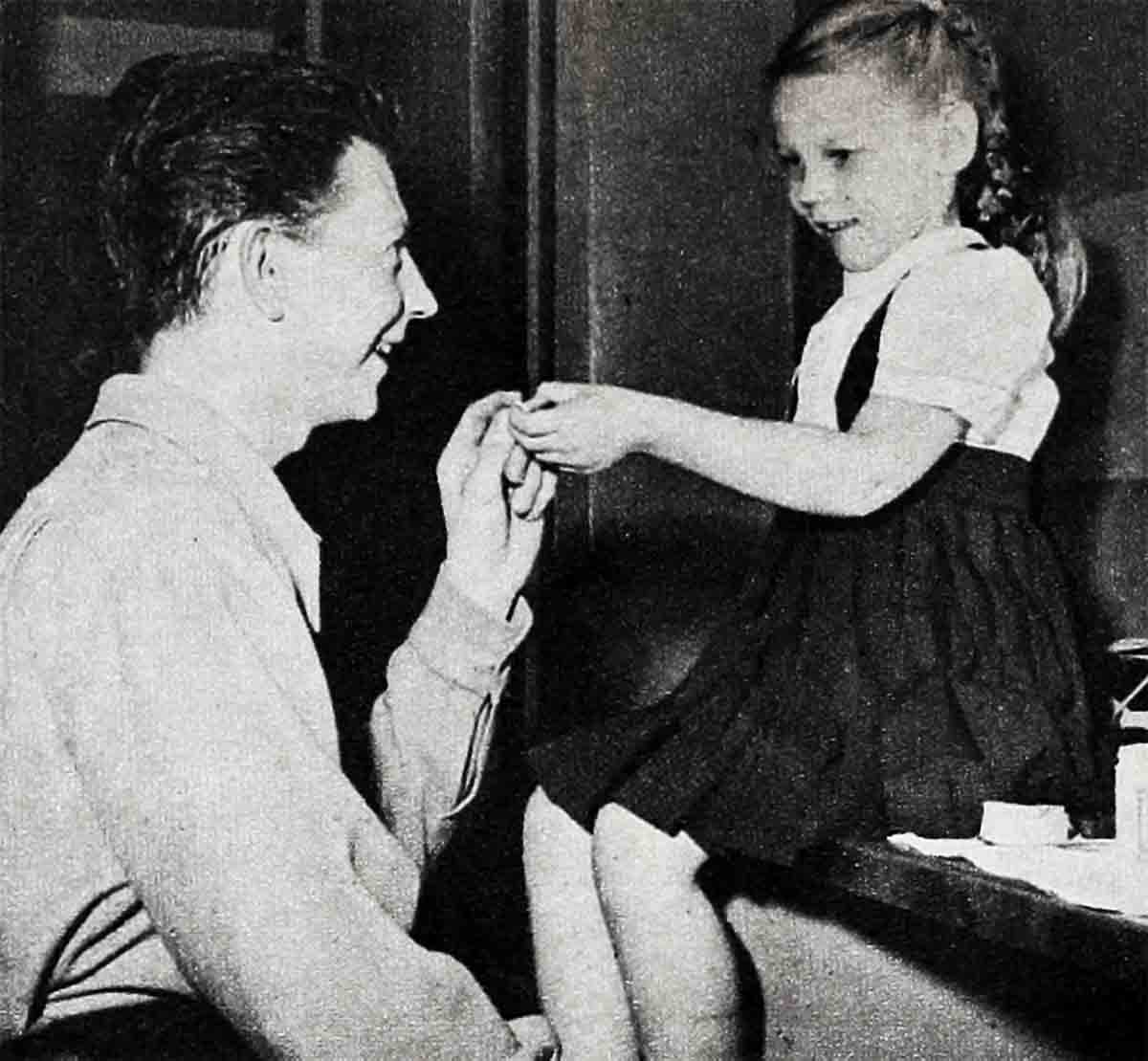

The letters pour in from older people who remember him on stage with his family when he was knee-high, and from the new younger generation, the kids who don’t recall his movie career in the prewar days. To keep up the pace, Donald puts in six and sometimes seven days (and nights) a week. He tries desperately to save Sundays for himself, to give him a chance to take his six-year-old Donna to an amusement park or the lion farm. There is a great bond between the father and daughter, and Donald says with a slight smile, “I think I can safely say that she really likes her mother and father.”

Sundays are the only days he has time to get out in the sun. He is perhaps the palest performer on record, as the overwhelming majority of daylight hours are Spent inside offices, sound stages, recording studios and theatres. When he does get some time off he goes in for golf, and sometimes will spend a few hours boxing in a gym to keep himself in condition. He tries, however, to go outdoors whenever he has the opportunity, and in the winter has grabbed a few short weekends for skiing. He is a natural athlete, as are most dancers because of their muscular coordination and sense of timing, and annoys friends when he picks up a racquet or bat or football and without any training betters those who have spent months in practice. Last winter he had three whole weeks to himself and spent so much time wondering what to do with himself that at the last minute he could squeeze only six days for a trip to Honolulu. His hesitation was perhaps because he likes so well to stay at home. Surprisingly enough, many of his friends are not in show business. He likes people and feels he can learn something from everyone, and talking shop is not his idea of a stimulating conversation.

The nervous type, he stays thin as a stick, and after ten years he weighs less than he did when he went into the Army. He watches his diet carefully, not from a weight standpoint but strictly for health. He drinks quantities of milk and orange juice, and eats sensible meals always well garnished with fruits, red meats and raw vegetables. If he slips up on sleep or food he is bedded by flu or some other bug, and the precious lost time frets him more than the illness itself. Others in the entertainment world, busy as they might be, wonder how Donald does it. Most of his activity is no doubt fueled by nervous energy, and no matter how physically tired he may be he always works to the hilt. When whipping up skits for his show with Sidney Miller and Sidney Kuller, he gets so enthusiastic that the writers sometimes have to slow him down. “I get in their hair,” he says. “Sid Kuller looks at me and says, ‘You’re pressing, you’re pressing’—which is a polite way of telling me to shut up.”

When he is aware he’s too tired, he has the common sense to refuse new assignments, and last year cancelled two television shows. But when he feels tiptop he can’t seem to get enough work. “I’d like to go on the Comedy Hour every four weeks instead of five, but picture commitments take up too much time.”

The show takes up the majority of his time and he tries to make it a well-rounded presentation with varied sets designed to please all types of people. He worries at criticism, no matter how small it might be. He worries about whether slapstick is still funny to people, he worries awake and asleep about every dance step, every dialogue bit in the show. Once in while a little thought creeps into his mind—“Let’s play golf. Why are you beating yourself? Come on, the sun’s out!”

“But, you see,” he smiles, “I can’t do it. I’m building to something. I’m trying to reach the point I’ve been striving for. Things have been happening fast and furious, and it may be tough right now, but when I’ve built my career in TV and pictures to where I want it, I can slack off a little.”

Enough people have told Donald that he has already reached the top, but he can’t believe that it’s true. Now the O’Connor needs only two things—repairs on his home life, and somebody who can convince him that he can play golf on a Tuesday without worrying. His fourth comeback has brought him back to stay.

THE END

—BY JANE WILKIE

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE AUGUST 1953

No Comments