Bruce Lee’s Game Of Death

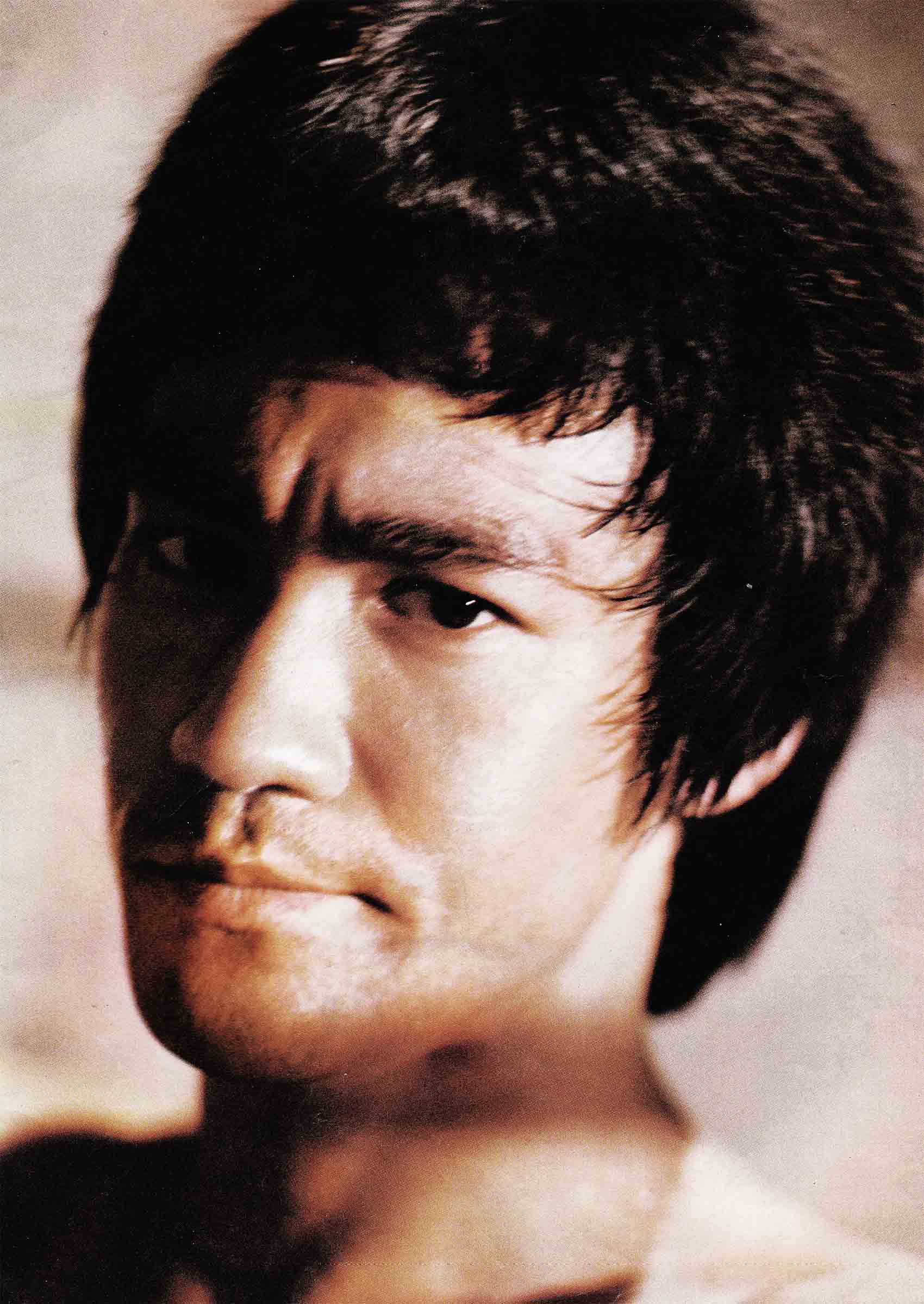

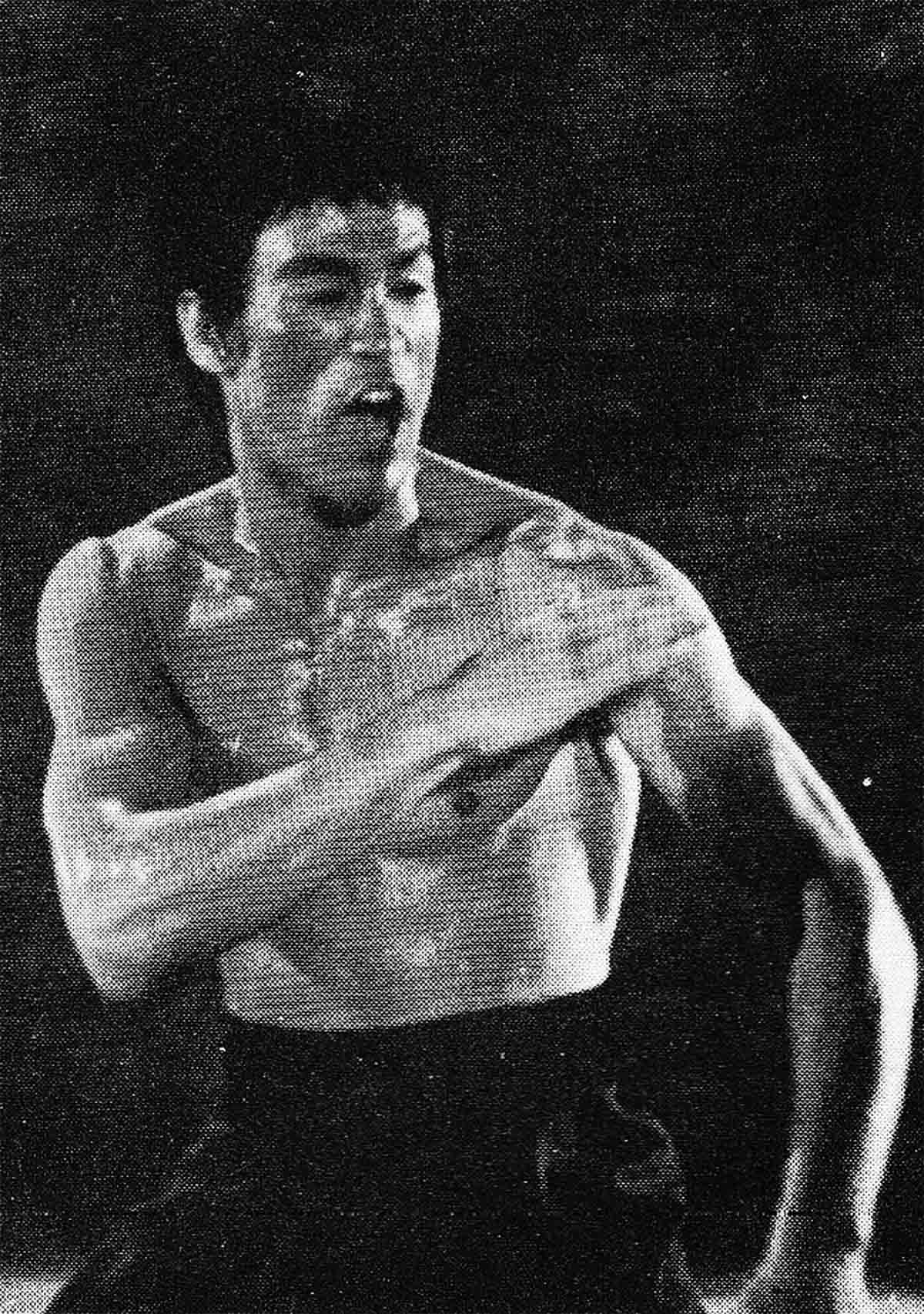

It has now been three years since that fateful mid-July night in Hong Kong that Bruce Lee the man they called Little Dragon—died. In the days preceding his death, Lee knew that, after a decade of struggle, he had finally won. In the last few years of his brief life, he had single-handedly transformed the face of the massive Far East film industry, sparked a martial arts craze which was to sweep the globe, and rocketed from bit parts in television serials to the role of highest-paid actor in the world. Lee’s career had exploded far beyond his wildest dreams, and 1973—the year of Enter the Dragon, Way of the Dragon and Game of Death seemed destined to seal his remarkable success. Truly, if ever death robbed anyone of something more than life, it robbed Bruce Lee!

But it is a curious quirk pf human society that in death heroes often attain heights which they could never have achieved in life. As it was with Rudolph Valentino, James Dean and Marilyn Monroe, so too was it with Bruce Lee. With his death, Lee passed into legend, and in the three years since that tragic evening, this legend took root and grew unchecked in the minds Of his countless fans and followers. Lee himself would undoubtedly have been embarrassed and uneasy at the adulation which is now heaped upon him by his adoring fans. “Look, I’m the same guy I’ve always been,” he once scolded one of his friends who had grown shy of approaching such a famous film star.

But as with Dean and Monroe, the Bruce Lee cult refused to die. Today, so long as his films continue their endless repeats in cinemas across five continents, the Little Dragon’s fans will line the pavements. As long as Kung-Fu is practised and mastered, his name will be remembered. It is this worship which has made Bruce Lee’s last, unfinished, action epic—the eerily titled Game of Death—the most eagerly awaited film in cinema history! Arid, perhaps, the most mysterious!

For three years the footage Bruce Lee managed to shoot for Game of Death has lain untouched in the vaults of Golden Harvest, the Hong Kong production company Lee helped build; from a mere idea into the second largest studio in the East. Until now, only the barest details about Game of Death have leaked from Golden Harvest. “He was an open man in life, but everything about him turned mysterious after his death,” commented a Hong Kong film director at Bruce’s funeral, pin-pointing the impending controversy which would later surround Lee’s last hours. This same comment could just as well apply to Game of Death. Under Lee’s own direction it was the most open of films, shot with the voluntary assistance of a score of Lee’s friends and acquaintances. After his death, the film became an enigma, caught up in the intrigue of the man’s private life.

Now the news from Hong Kong is that Game of Death is back in production and tentatively scheduled for release later this year. Although officially the wraps are still on tight, enough detail has leaked out for an accurate picture to be pieced together. This, then is the story behind probably the last great Kung-Fu movie ever . . . Bruce Lee’s Game of Death!

Game of Death was born at the precise moment Bruce Lee’s career began to erupt internationally. To producers in Hong Kong, the name Bruce Lee on the marquee was already a gilt-edged guarantee of at least a million dollars. Lee’s first two films—The Big Boss and Fist of Fury (titled respectively Fists of Fury and The Chinese Connection in the U.S.)—had shattered box office records throughout the Far East and reaped extraordinary profits for Golden Harvest. So great was Lee’s impact on the Eastern industry that the Chinese producers began thinking’ seriously for the first time ever of exporting their wares to the West. Kung-Fu, it was felt, might just take off.

The first producer to take the plunge was Run Run Shaw, head of the giant Shaw Brothers Studios and acknowledged czar of Oriental film-making. His King Boxer (Five Fingers of Death in the U.S.) starring Lo Lieh, was the Westerners’ first taste of Kung-Fu, and it was immediately obvious that a KungFu invasion was imminent. In just eleven weeks, Five Fingers notched up a cool $3,800,000 in the U.S. Alone!

After several other Shaw Bros, movies had been released in the West, Golden Harvest decided to launch Bruce Lee’s first effort, The Big Boss. Standing head and shoulders above any other actor in the East, Lee’s appeal was a foregone conclusion. Overnight, the Western fans transformed him into an international superstar!

At this time, Lee had already completed his third film—The Way of the Dragon (Return of the Dragon in the U.S.). Way of the Dragon was Bruce’s first solo film-making effort. Besides playing the leading role, he had elbowed out veteran director Lo Wei and taken control himself, working from his own script. Perhaps more importantly, he had technically ‘left’ Golden Harvest and had set up his own film company—Concord—together with Raymond Chow, the Big Boss of Golden Harvest. The move meant not only that Lee would receive a cut in the profits from his films—an unheard of arrangement in the old fashioned Hong Kong film world—but that from now on he would have complete say in what he was doing. Lee’s ambition, so often the driving force in his life, demanded that he pull the strings. For the first time in his career, he was in a position to do just that. What he decided on was a film which he had vaguely planned in his mind, a film which would provide the ultimate showcase for the martial arts. For many months his concept of the film was so sketchy that he did not even give it a working title. Later he would refer to it as Game of Death.

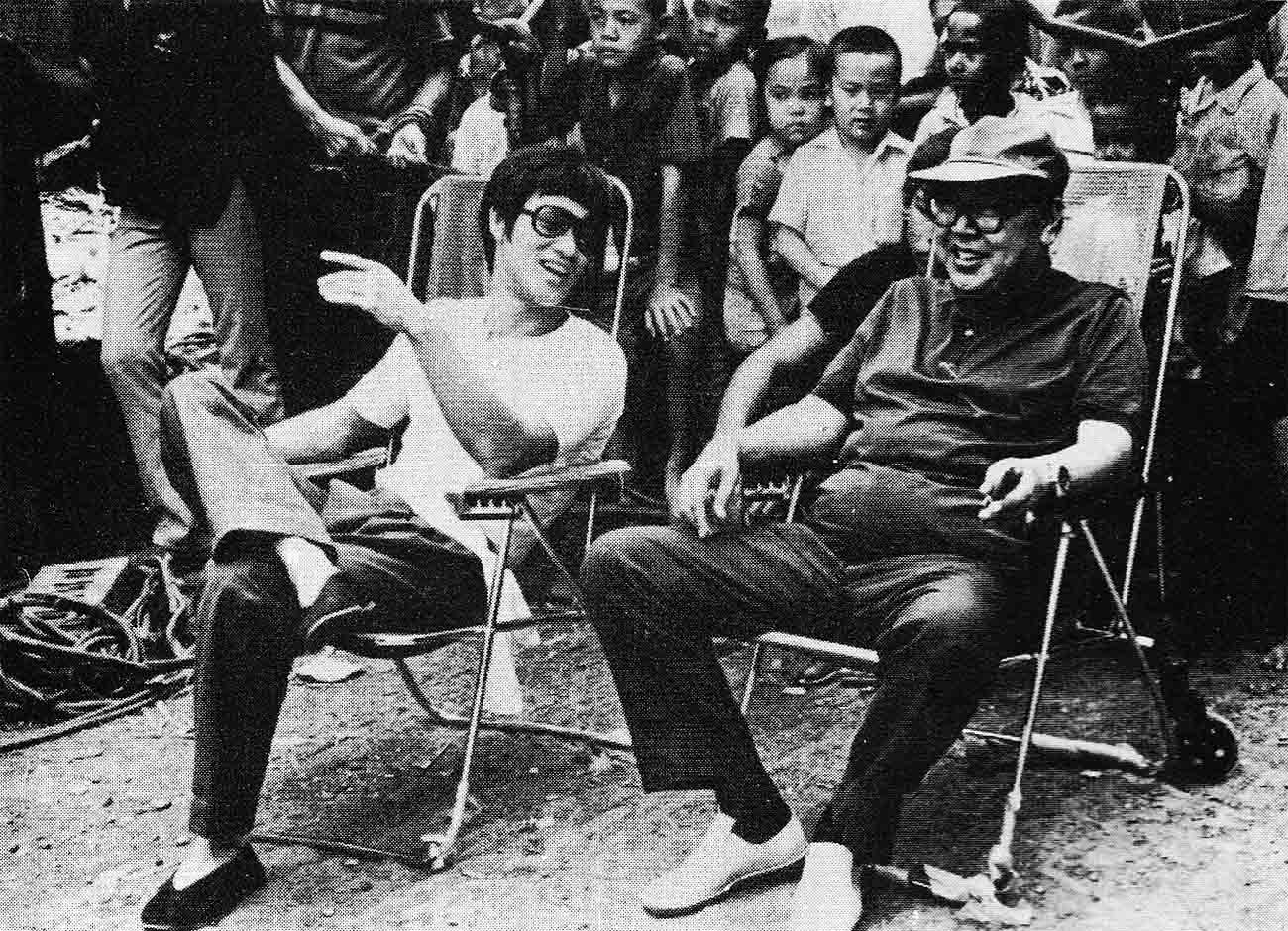

Lee began actual filming for Game of Death long before the ideas in his mind had congealed into anything even resembling a story line. He had originally planned to take a breather after Way of the Dragon was complete, work out a plot, write a script, choose a cast and crew and then begin cranking the camera. However, this schedule was thrown into confusion by the appearance of a giant from Milwaukee Kareem ‘Big Lew’ Abdul-Jabbar. Bruce and Lew—ace centre player for the Milwaukee Bucks and one of the top basketball players in America—had been friends for many years. When Bruce heard that Lew was planning a visit to Hong Kong, he wrote to him suggesting that they shoot some footage together for Game of Death. Perhaps his father’s theatrical background helped Bruce see the showmanship possibilities in a Kung-Fu bout between himself and a man a full two foot taller than him! Lew readily agreed and shortly after his arrival visited the Golden Harvest studios and began work.

Although Jabbar could never claim to come within a mile of equalling Lee’s martial prowess, the scenes which unfolded were apparently highly realistic and entertaining, a masterly mixture of the sublime and the ridiculous. Shooting took a full week, and when it was complete, cast, crew and extras were all profoundly pleased. Everyone, that is, except Big Lew’s manager back in the States. Jabbar, at the peak of his profession, is about as heavily insured as the Crown Jewels. When his manager heard he had been spending his Hong Kong holiday sparring with Bruce Lee, he had apoplexy.

Big Lew’s departure heralded not only the end of his cameo role, but also the suspension of the whole project. Lee’s international fame suddenly caught up with him with a vengeance. As Big Boss—followed by Fist of Fury—stomped across first Europe then America, re-writing box office receipt books and stringing queues of fans five deep around city blocks, producers from Hollywood to Hungary began falling over themselves to sign up the Little Dragon. For Lee it was as if the heavens had suddenly opened, raining contracts down on him like hailstones. For years he had found it impossible to break down the racial prejudices of the West—and Hollywood in particular. Now he was at the centre of a whirlwind.

At the head of this million dollar queue stood Warner Bros. Warner’s production executive Fred Weintraub flew to Hong Kong to offer Conford the chance to co-produce “the first martial arts film made by an American company”, as the studio publicity machine later dubbed the venture. It was an offer Lee and Chow could not refuse. Although the total budget for the film to be called Enter the Dragon—was just $600,000, a fraction of the cost of most full-scale Hollywood projects, by Hong Kong standards it was astronomical. Obviously Warners were offering Lee the chance of capturing the West, lock, stock and barrel. It was his biggest break yet and he was wildly enthusiastic. Game of Death was postponed indefinitely.

Plots and Plans

“At present I am working on the script for my next film. I haven’t really decided on the title yet, but what I want to show is the necessity to adapt oneself to changing circumstances. The inability to adapt brings destruction. I already have the first scene in my mind. As the film opens, the audience sees a wide expanse of snow. Then the camera closes in on a clump of trees while the sounds of a strong gale fill the screen.

“There is a huge tree in the centre of the screen and it is all covered with thick snow. Suddenly there is a loud snap and a huge branch of the tree falls to the ground. It cannot yield to the force of the snow so it breaks. Then the camera moves to a willow tree which is bending with the wind. Because it adapts itself to the environment, the willow survives.

“It is this sort of symbolism which I think Chinese action films should seek to have. In this way I hope to broaden the scope of action films.”

When Bruce Lee said these words to a newspaper interviewer in Hong Kong, his next film was Way of the Dragon. However, it is more than safe to assume that he was thinking of the film which would later become Game of Death. The story that Lee evolved echoed precisely these words, a story highlighting the necessity for adaption and change, specifically in the realm of martial arts. As such it was a story summing up virtually the whole of Lee’s martial arts career.

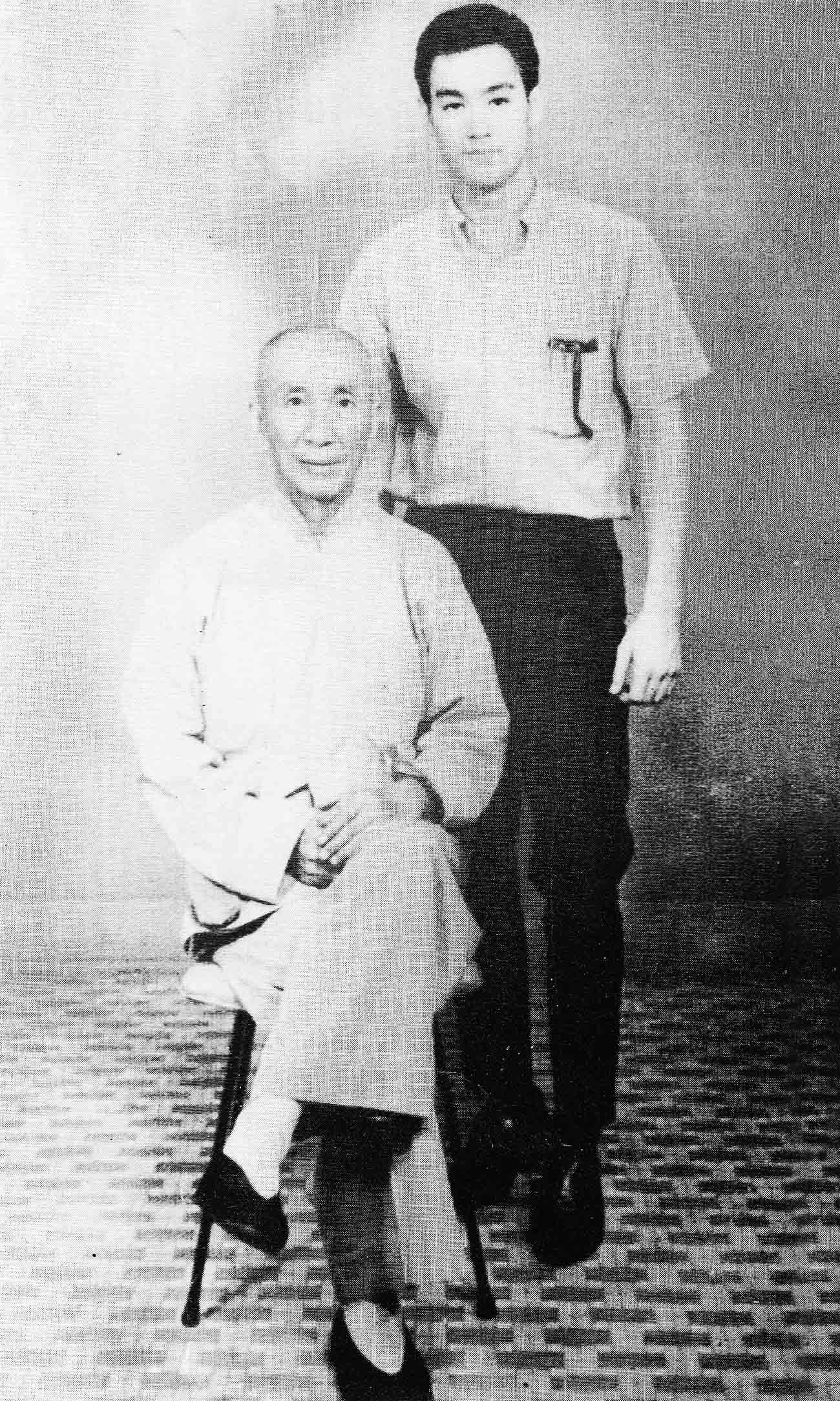

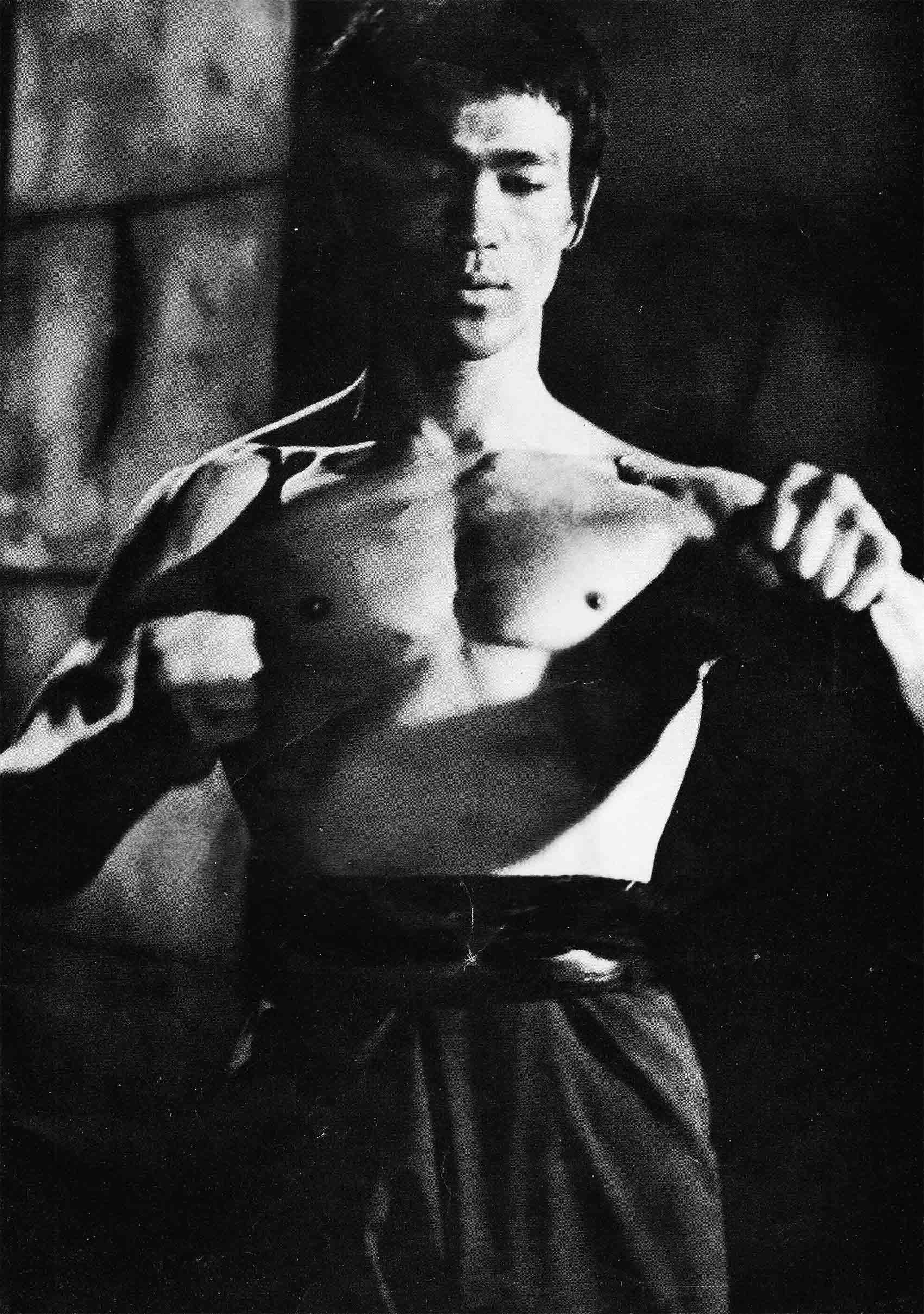

Lee began his Kung-Fu training under a master of the Wing Chun school of Kung-Fu, an old man by the name of Yip Man. Wing Chun is a curious style of Kung-Fu which was developed by a woman—Yim Wing Chun—some time between the 16th and 17th centuries as a protest against the more rigid, traditional schools. After studying Kung-Fu under a Shaolin nun, Madam Yim had come to the conclusion that the traditional styles were in danger of being suffocated by their own traditions. She drastically cut the number of katas required, placed the emphasis on close quarter fighting and came up with Wing Chun.

Learning under a Wing Chun master, Bruce was instilled with the knowledge that simplicity and directness were far more useful attributes than an ability to recall hundreds of katas. Under Yip Man, the young Bruce mastered the art of fighting without having to follow a pre-set pattern. In particular, Wing Chun taught Bruce to use an opponent’s strength and ‘bend with the wind’, rather than attempt to dominate it. Already the roots of Game of Death adapt and yield—were beginning to grow.

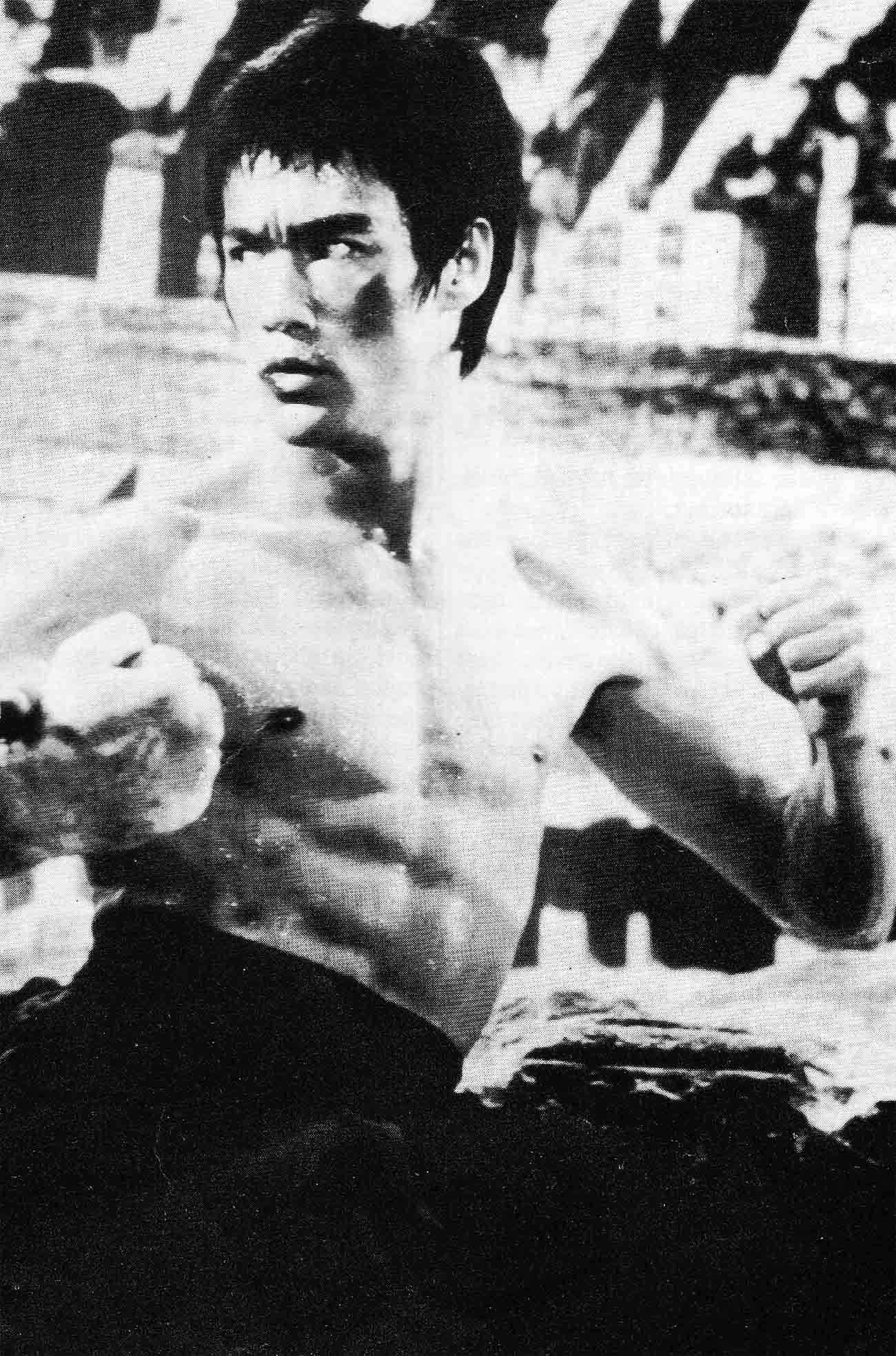

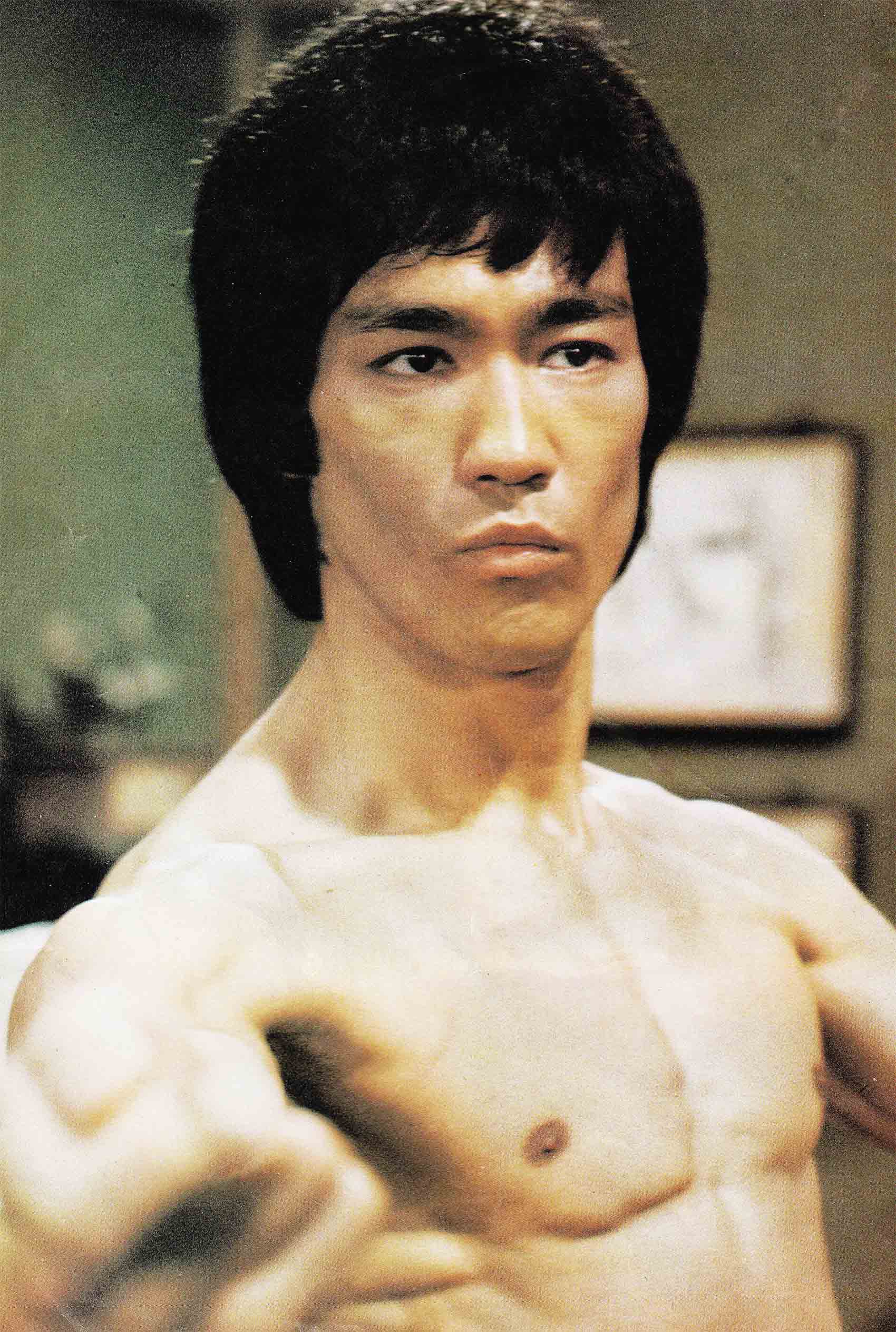

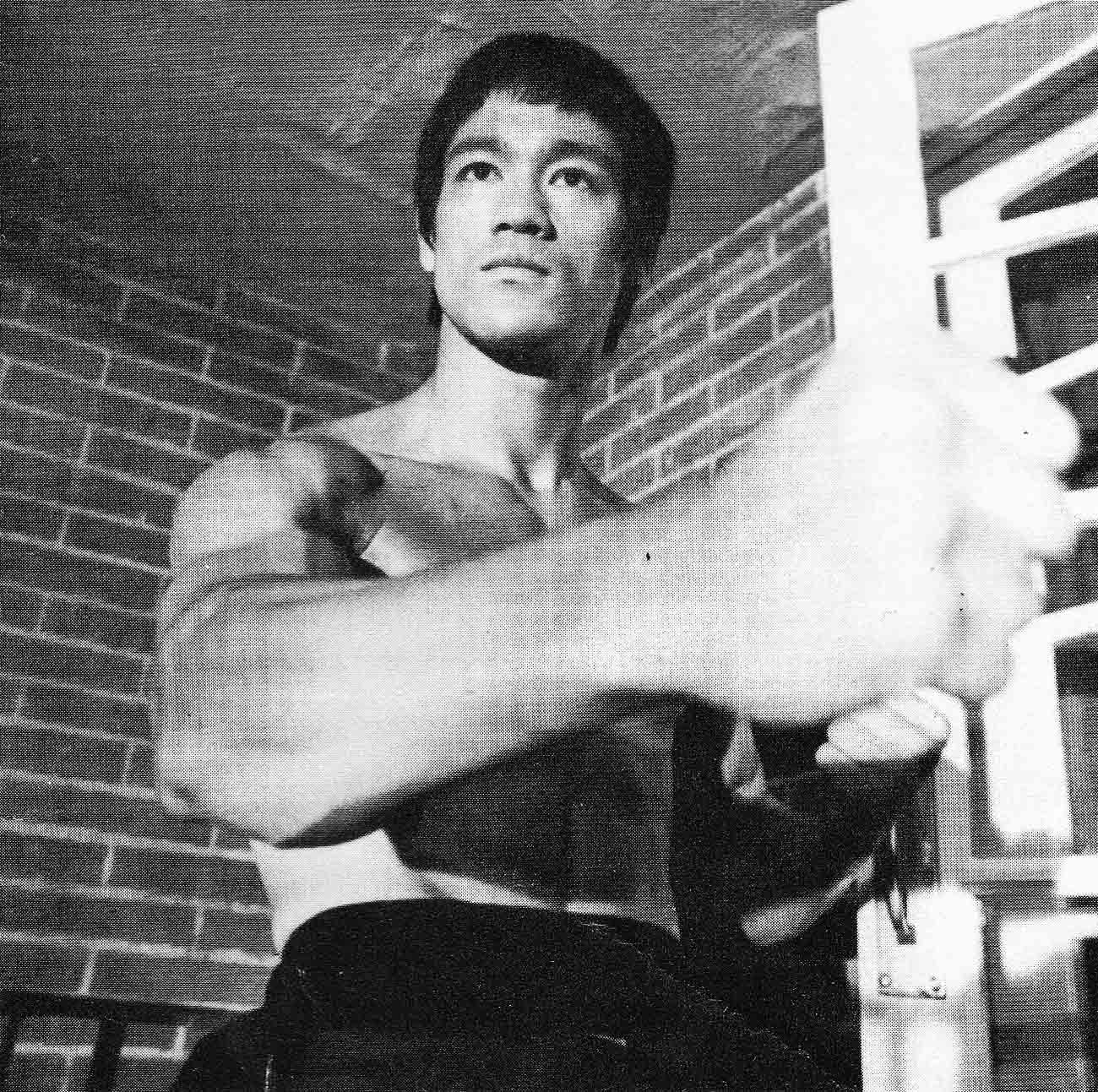

But even Wing Chun was too restrictive for Lee. Why not, he thought, throw all style out the window and try for total fighting freedom? The ‘style’ which he subsequently developed himself was, in fact, no style at all. Jeet Kune Do—The Way of the Intercepting Fist—allowed its disciples to use literally every trick in the book, from Western boxing to wrestling to judo to Thai kick boxing.

“I am no style, but I am all styles,” Lee would lecture his pupils. “You don’l know what I am going to do, and ever I don’t know what I am going to do. My movement is the result of your movement; my technique is the result of your technique.”

In retrospect it seems certain that this is what Lee was intending to show in Game of Death. All his martial career he had been breaking rules, stepping on the toes of the traditionalists, exhorting martial artists to step through the mass of styles which held them in check. If ever Bruce Lee had a message to pass on to his pupils, this was it. It became his life’s work. After his death it was even rumoured that he had been assassinated by a traditionalist master angered by his blasphemy. Game of Death was to provide living proof of the validity of his belief.

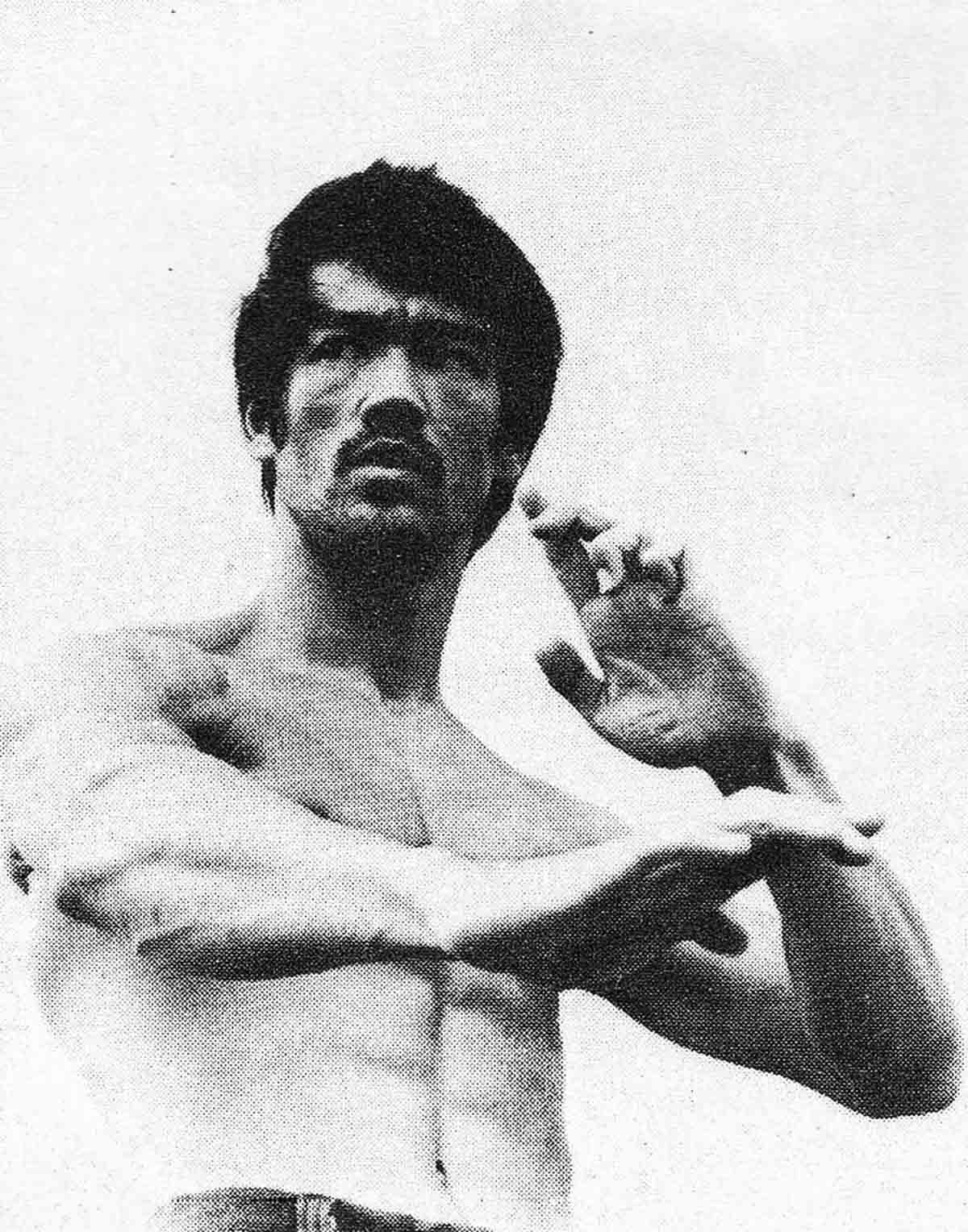

Dan Inosanto, an old friend of Lee’s who appeared with him in some of the scenes which were completed for Game of Death, once spelled out Bruce’s real intentions clearly in an interview with an American martial arts magazine. The point behind Game of Death was, he said, that the martial artist had to be better than the martial tradition. All the fighters Lee picked as his opponents in the film depicted a certain tradition.

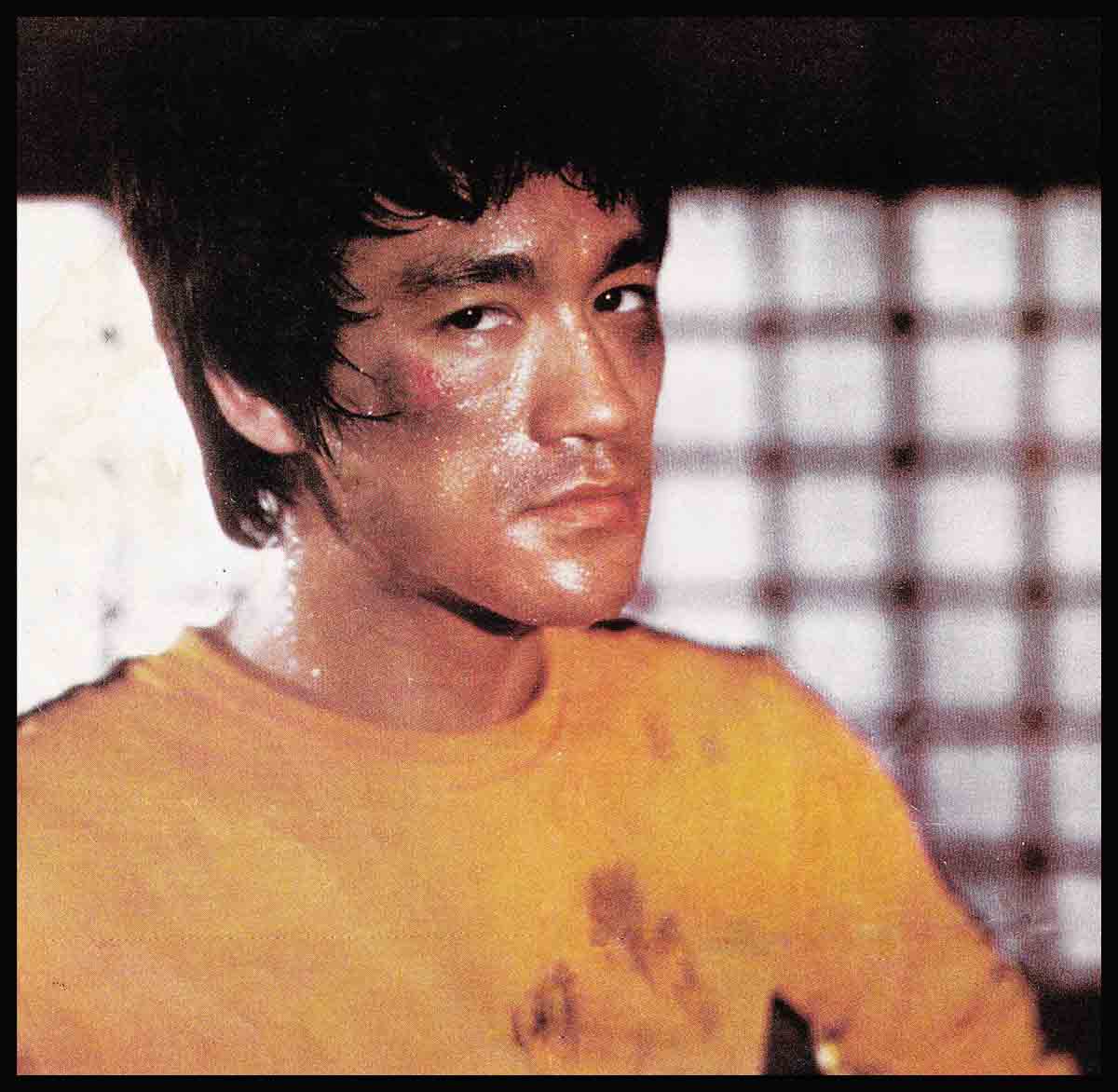

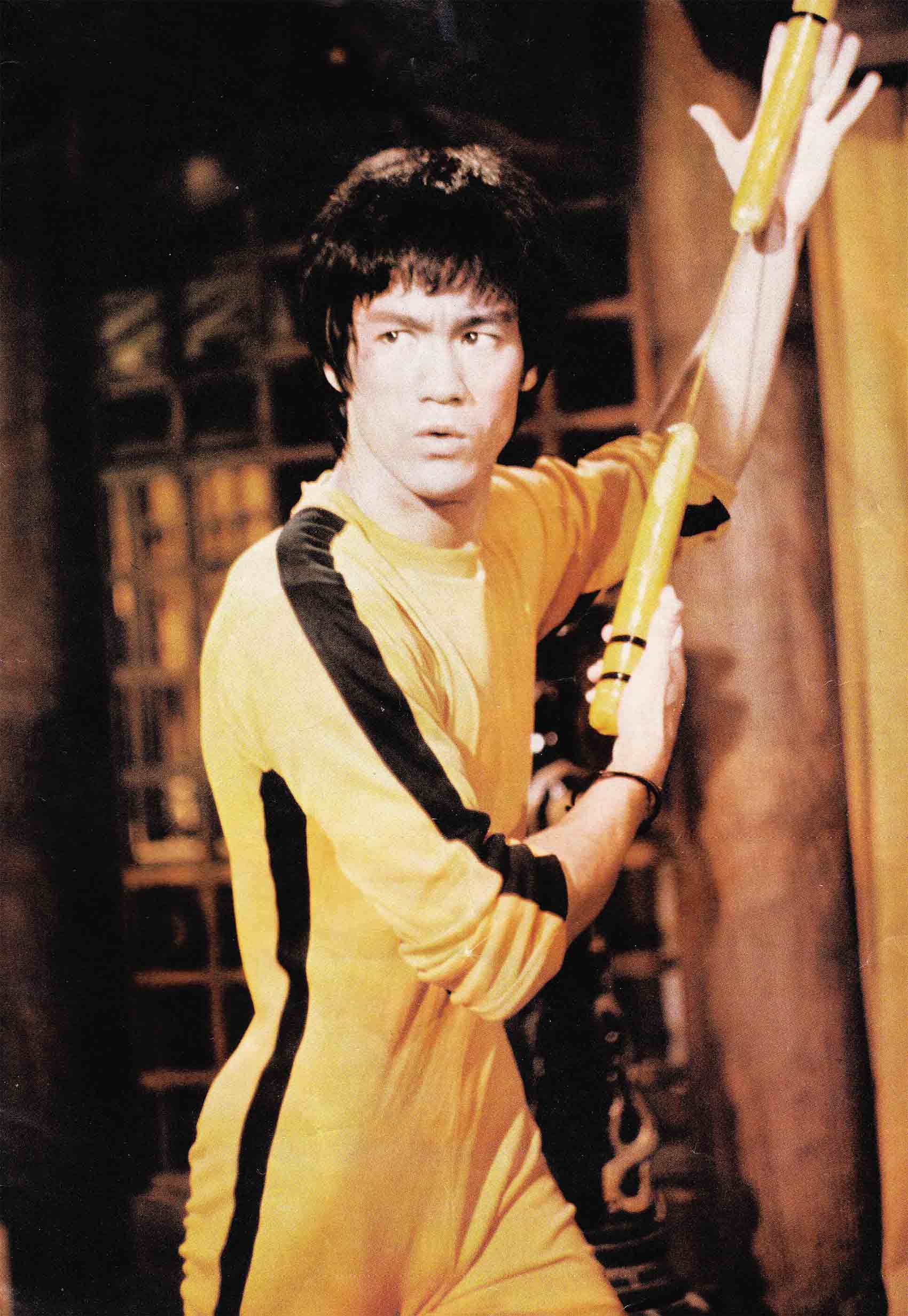

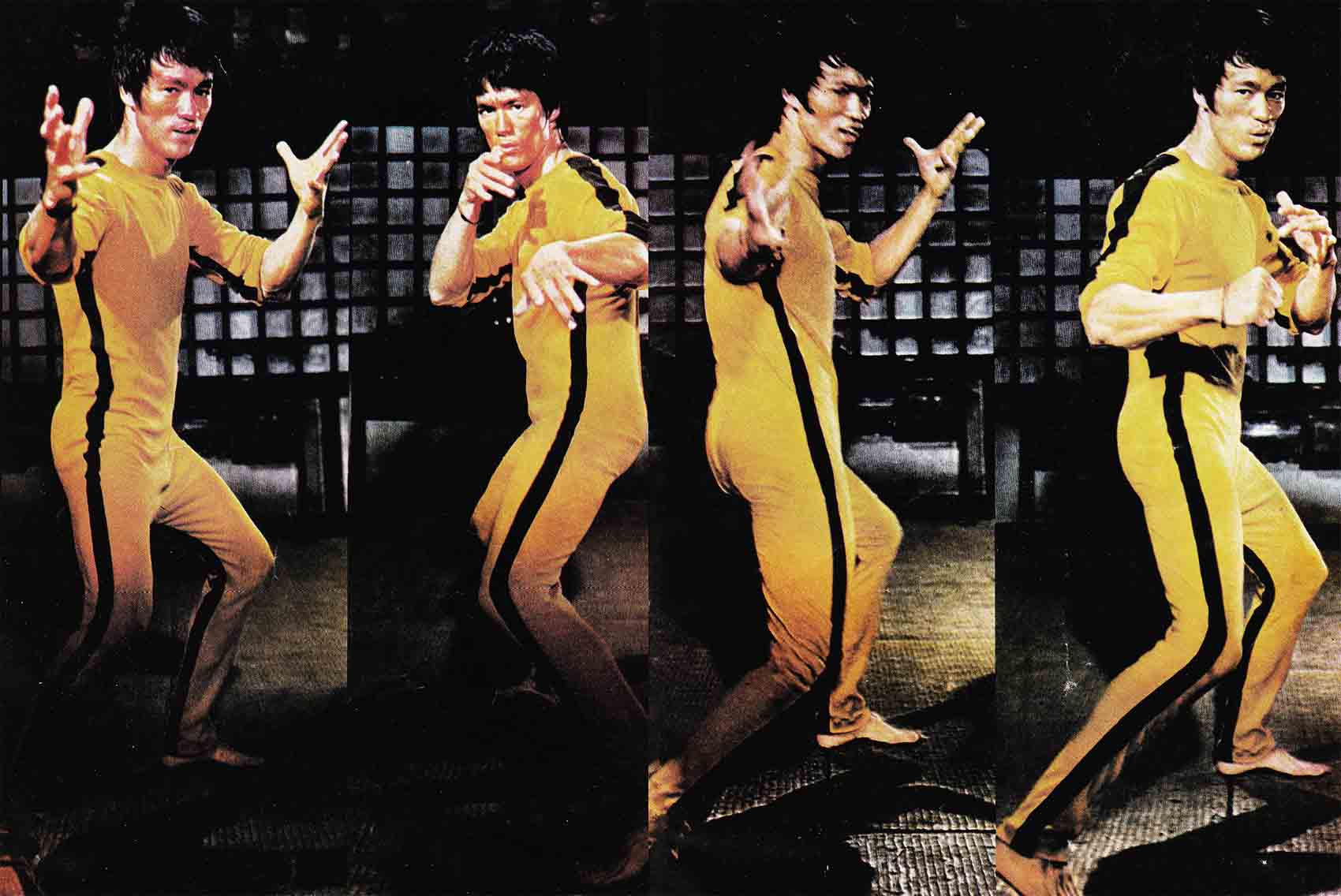

“Even me,” commented Inosanto, who played the part of a Filipino ‘escrima’ in Game of Death, “I’m dressed in a typical Moslem outfit. But Bruce Lee wears that yellow outfit and looks like the jet set, modern. Everybody else is in traditional garb. Again, his thing is bringing out that the greatest thing is to be better than the tradition.”

As Inosanto himself pointed out, Lee’s other films all carried messages for the martial artist. For instance, the epic Coliseum battle with Chuck Norris in Way of the Dragon showed how being a practical fighter is often not enough. Initially Lee appears to be losing to Norris because he is fighting in a purely practical fashion. It is only when he switches to what Inosanto labelled an ‘offset’ rhythm that he begins to get the upper hand. What was different about Game of Death , however, was that Lee appears to have balanced the entire film upon his philosophical message of ‘adapt and bend’.

So far as can be judged from what he said before his death and from the footage that he did manage to capture, this is what Bruce Lee had in mind as the story line of Game of Death.

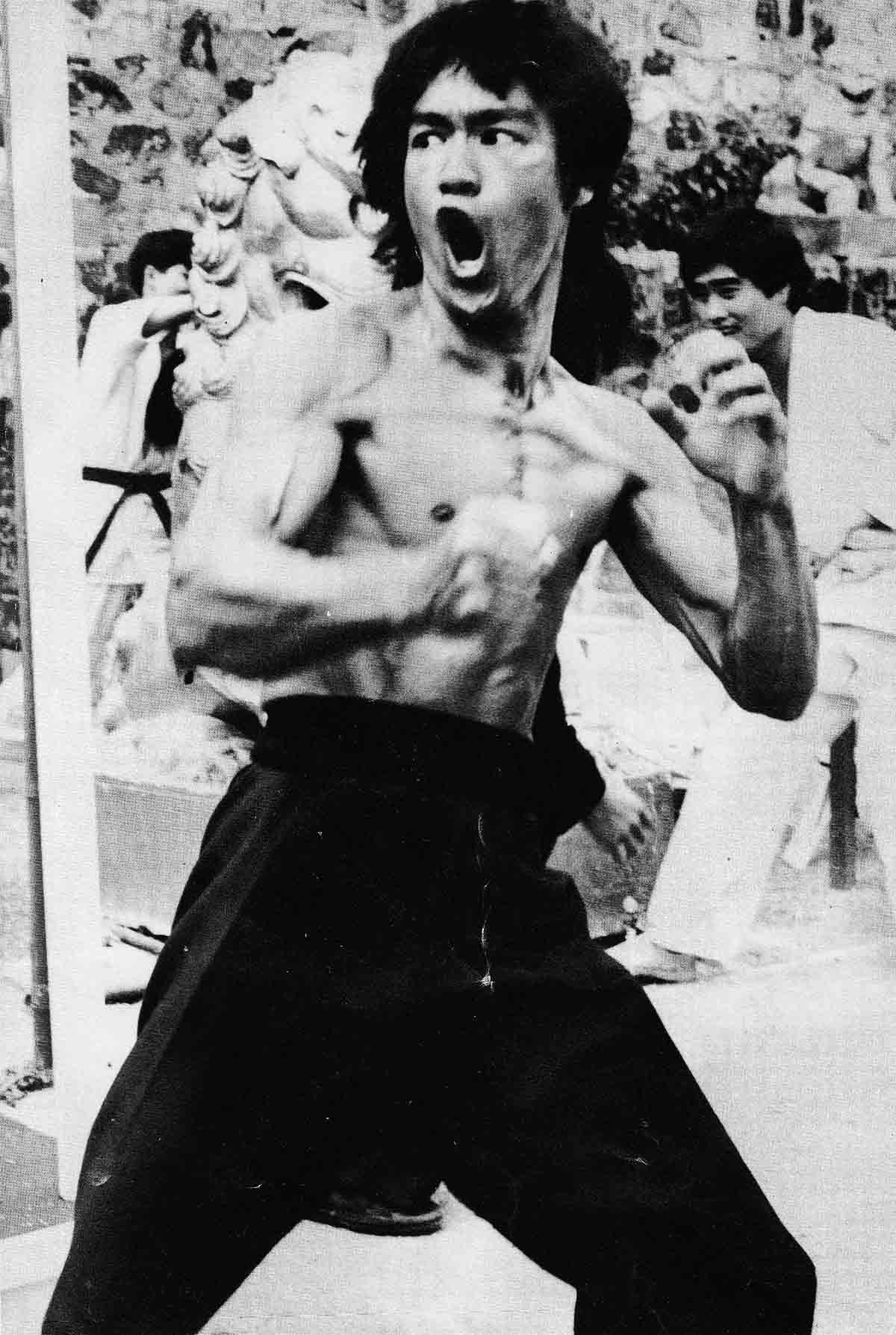

A national treasure is stolen and spirited away to Korea where it is hidden on the top floor of a pagoda-style temple. This pagoda is, in fact, a training school for martial artists of differing styles, and each floor is given over to students of the various forms of defence. The First floor is ruled by a Karateka guard; the second by a hapkido exponent; the third by a Kung-Fu disciple; the fourth by the escrima and the Fifth and Final floor by a fighter whose style is as close to Bruce Lee’s Jeet Kune Do as possible. That is, it encompasses ah the other styles but also supersedes them. Bruce Lee, accompanied by four other martial artists, travels to the island on which the pagoda stands, fights his way through the various floors—meeting finally with the giant Kareem Abdul-Jabbar who is the Master of the Unknown—and wins back the treasure. To ensure that no guns or weapons are used and that the action relies entirely on martial expertise, metal detectors scan the island.

It was all there—the fighter unburdened by restrictions taking on the traditionalists and beating them into the ground. As a climax, Bruce had planned a twist to put a real sting in the tail of his plot—Lee, the master of Jeet Kune Do, master of the ‘anything goes’ style versus Abdul Kareem Jabbar, master of no style, just master of himself. On this final, fifth floor, both sides threw away the rule books and relied entirely on their own native, natural skills, man-to-man! Some Fight! Some film!

The Celluloid Battlefield

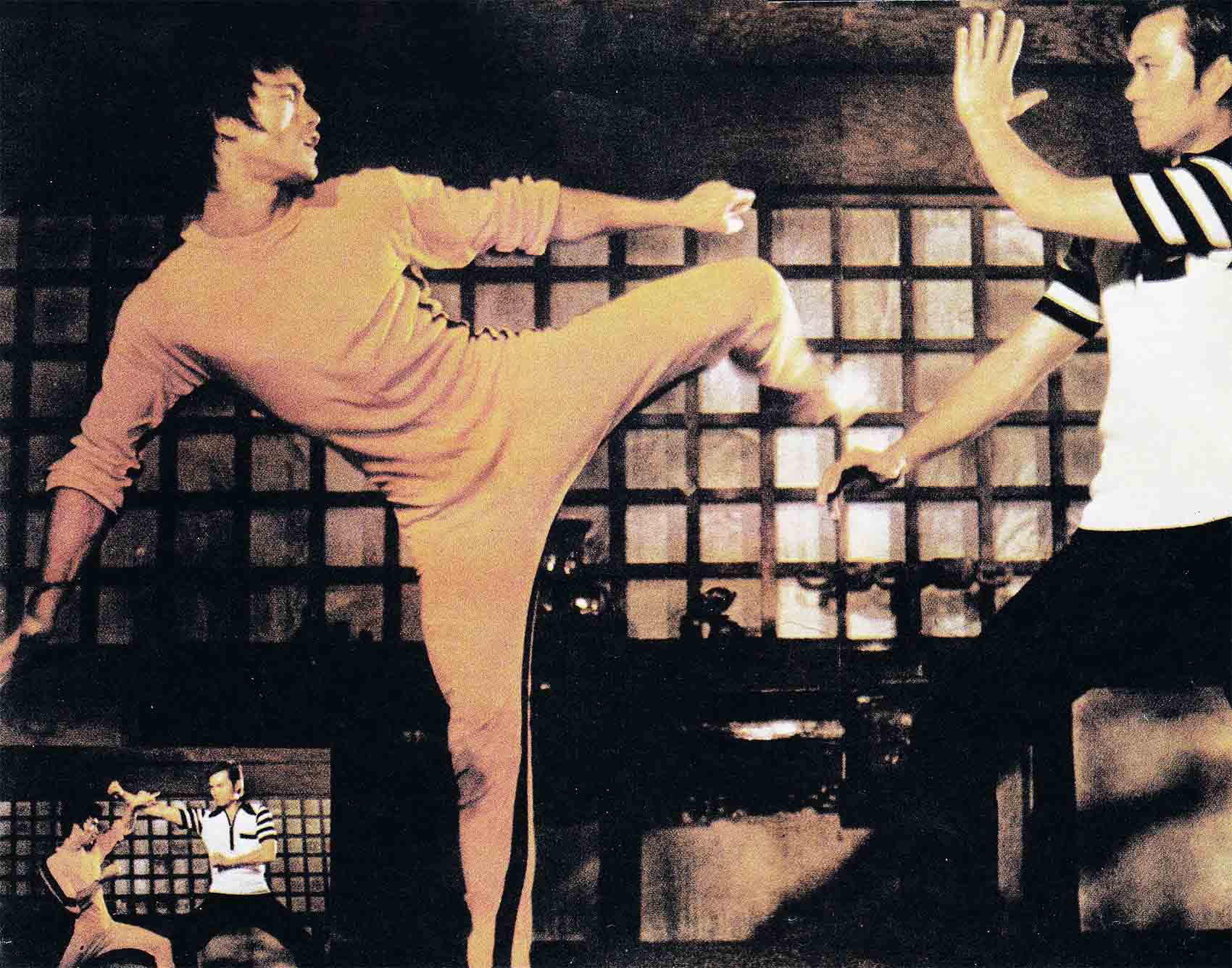

Way of the Dragon pointed the way for Bruce Lee when he sat down to plan Game of Death in more ways than one, not the least being the choice of actors and actresses to fill the pagoda’s lethal levels. In his third film, Lee had packed his cast list with genuine top-level martial artists in preference to actors. Consequently, it included such fighting talents as Yang Sze, Shotokan champion of South East Asia, and Chuck Norris, seven-time Karate champion. This move towards authenticity rather than good acting paid huge dividends for Lee; indeed his epic battle with Norris must be one of the most gripping action episodes ever filmed.

This casting policy was carried over from Way of the Dragon to Enter the Dragon. On Lee’s insistence, such martial masters as Bob Wall, Angela Mao and Jim Kelly were included, along with a host of other martial artists drawn from all over the globe. Even co-star John Saxon—better known to film fans for his good looks than his fast fists—was a Kung-Fu enthusiast.

Lee was determined that expertise would continue to be the hallmark of his films and to this end he envisaged Game of Death as a sort of celluloid battlefield for the cream of the world’s martial masters. It was his wish that the film would sponsor the most glittering array of fighters ever assembled.

Big Lew was perhaps little more than a casting department’s happy accident—the right man on the right spot at the right time. The other stars of Game of Death, however, were chosen after much deep thought by Lee. Unfortunately, what roles they were to play Lee more often than not kept to himself. One star we are certain about though is Dan Inosanto, whose role as keeper of the fourth floor was one of the three fight scenes to be fully completed before Lee’s death.

Inosanto first met Bruce Lee in 1964 at a Californian martial arts demonstration. At this time Inosanto was proficient in a number of the arts, notably Korean, Okinawan and Japanese karate. He was introduced to escrima by Ed Parker, the grand old man of American martial arts. Inosanto studied under escrima’s finest masters in both California and Hawaii, names which included the likes of Angel Cabales, Max Sarmiento, Braulio Pedoy and Subing Subing. In time he also had mastered the art.

Escrima (together with its varian kali and arnis) is the ancient Filipino art of stick fighting.

Today, its development has led it into the realms of sword and dagger combat, but essentially its basis is the block and attack movements of the staff. The art was named by the Spanish conquerors—escrima, meaning skirmish—before they realised its lethal power and banned it. In the north Philippines the movements were kept alive in dance form. In the Muslim region in the south, the natives repelled the conquerors and continued the art intact. Today it still survives unchanged in the south where the Muslims, still a rebellious and proud people, are conducting a bitter and bloody civil war against the central Filipino Government.

In Game of Death, Danny Inosanto wears the costume of a Muslim escrima, notable for itsMoro headband. Although escrima has in recent years been somewhat swamped by the popularity of Kung-Fu, another film besides Game of Death has been made highlighting the art—The Pacific Connection.

After their meeting in 1964, Bruce and Danny became close friends and several years later began seriously studying together. When Bruce landed the part of Kato in the Twentieth Century Fox series The Green Hornet,he had a lot of time on his hands to devote to Kung-Fu and training with Danny. Inosanto stood in for actor Mako Iwamatsu in one Green Hornet episode, titled ‘The Praying Mantis’.

In Hong Kong, when Lee was putting together a cast list for Game of Death, he immediately thought of his old friend Inosanto as the guardian of one of the pagoda floors. He forwarded a China Airlines ticket to Inosanto, who flew out as soon as he could manage leave from his physical education teaching duties. He remembers how Linda, Bruce’s pretty American wife, met him at Kai Tak airport because “Bruce always got mobbed.” Within a day the two men were hard at work.

The third and final fight sequence to be completed was the hapkido bout with Chi Hon Joi, a seventh degree black belt. Unfortunately little is known about this episode, except that two of Bruce’s allies are killed by Chi Hon Joi before he manages to overcome the hapkido master. Hapkido, like escrima, is another non-Chinese martial art, hailing originally from Korea. Actually it has only recently been formalised from a mass of ancient Korean teachings dating back some thirteen hundred years. Although its origins are rather obscure, it appears certain that the dreaded Harang Do, the samurai-style knights of ancient Korea, included it in their arsenal. Later the art was carried on by isolated monks who, forbidden by the emperors to carry arms, used it as a defence technique. Modern hapkido relies much on high kicks which means that physical perfection is a must.

It is interesting to note that besides Chi Hon Joi, Lee considered a second hapkido expert for a part in Game of Death, the now-famous ‘Lady Whirlwind’, Angela Mao. Angela, another Golden Harvest discovery, has, more than any single person, played a leading role in exporting hapkido to the West and popularising it there. She began her martial film career in the Golden Harvest production Angry River and followed it up with the aptly named and enormously successful Hap Ki Do. However, the role most Westerners will remember her in is as Bruce Lee’s little sister in Enter the Dragon Since then she has completed a number of films for Golden Harvest—Deep Thrust, Hand of Death, Back Alley Princes and The Fate of Lee Khan. All have proved box office hits both in the Far East and the West. Now she is one of Hong Kong’s top three actresses. This year, Golden Harvest plan to promote her even harder as the star of their martial extravaganza The Himalayans. Although no-one knows what Bruce Lee had in mind for her in Game of Death, one thing is certain, she would not have failed his judgement.

For the rest of the planned cast, their roles can only be guessed at. Shotokan champion Yang Sze, who appeared as the hired Japanese assassin in Way of the Dragon, was scheduled to appear and it is not unreasonable to assume that he would have been given the part of master of the first floor, the karateka. Bruce’s real-life girl-friend, Betty Ting Pei, was also to have received a role. (As Betty recently told us in Hong Kong, she was also to have had a part in Enter the Dragon, but “I got sick and my mother sent me to the hospital”.) However, she too was not told what her part was to be.

Other martial artists and actors reportedly due to appear were Wong In-Sik, James Tien, Jhoon Rhee, Hung Kam-Po and, apparently, Chuck Norris himself.

The biggest name in acting circles to appear was that of George Lazenby, the Australian actor who shot overnight from male modelling and TV commercial making into Sean Connery’s shoes as the ‘new James Bond’. Lazenby had been hanging around in California when one day he had chanced to wander into a local movie house showing Bruce Lee’s Fist of Fury. According to Lazenby, he was so knocked out by what he saw he “caught the next plane to Hong Kong” and negotiated a part in Game of Death.

Taky Kimura, another old friend of Bruce’s from the American years, was also offered a part. Now an instructor in Seattle—and today considered the world’s leading Jeet Kune Do practitioner—Taky received a ticket to Hong Kong in his post box out of the blue. Taky rang Bruce, who explained he wanted him for Game of Death. At first Taky declined, saying he was no film star. However Bruce replied: “Everybody looks good in my films,” and Taky just had to agree. Twelve hours later he answered the phone only to learn Bruce Lee was dead.

Action!

Game of Death was without a shadow of a doubt strictly a one-man show. And that man, of course, was Bruce Lee himself “His movie-making is like his fighting,” Dan Inosanto said recently. “He just did it. He didn’t know until the night before exactly what he was going to do. Then he put it together. He made up the story details as he went along, spontaneously. That’s the way Game of Death was.”

As Inosanto noted, most of Bruce Lee’s movies came from inside Bruce Lee’s head, and in Game of Death this unique style of film-making was taken to its extreme. Lee had been given a totally free hand with Way of the Dragon and he had revelled in the experience. Enter the Dragon, following hard on the heels of Way of the Dragon, must have come as a big anti-climax for the Little Dragon, what with having to once again buckle under to a scriptwriter, director, cameraman and so on. With Game of Death he was breathing free air again. Everything could be done exactly as he wished it.

It would seem perhaps that working with such a dictator might try the patience and temper of even the most good natured actor or actress. Not content with just outlining what was required, Lee would put a performer through his or her paces all the while shouting directions from the sidelines. Because the soundtrack of Hong Kong films is always dubbed in later, he could work like the silent directors of old, coaching actors even as the cameras turned for a final take.

It would certainly seem to be an off-putting experience filming under the direction of Mr, Lee, but in fact Danny Inosanto, making his first-ever full-length film, said it was in fact quite the opposite. When he first arrived, Danny was one nervous martial artist, afraid that he would ‘foul up’ a Bruce Lee movie. However, immediately his friend put him at ease. Shortly after Danny’s arrival, Bruce began outlining the fight plans he had churning around in his head. For the first three or four days the two men rehearsed the details with Bruce using a video-tape machine (a technique he had pioneered during his Green Hornet days). What he did was to film a rehearsal with video and then play it back immediately. What he wanted was not only the best martial skills, but also the movements that would show up best on camera. As Inosanto later commented, “He was a genius.”

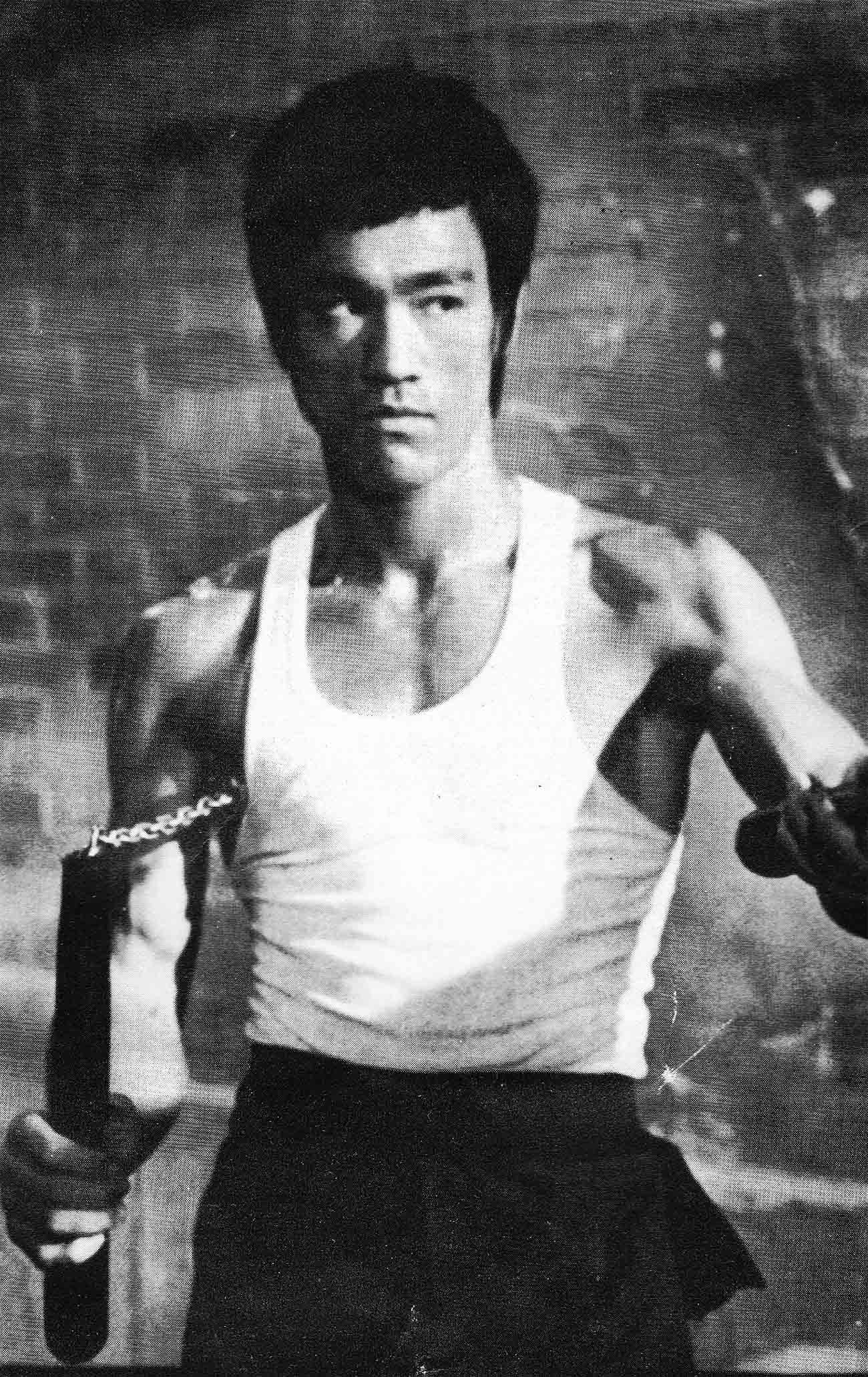

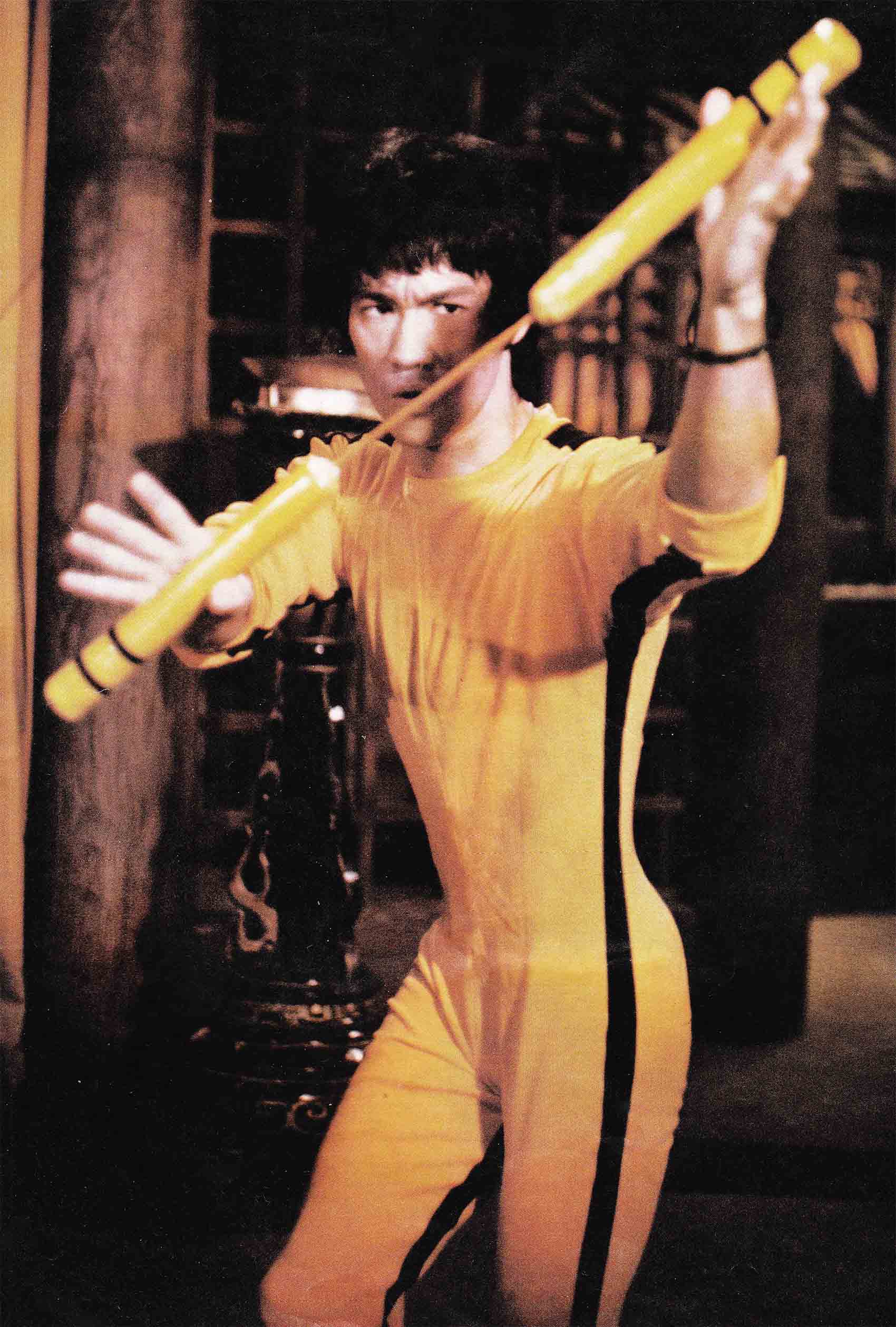

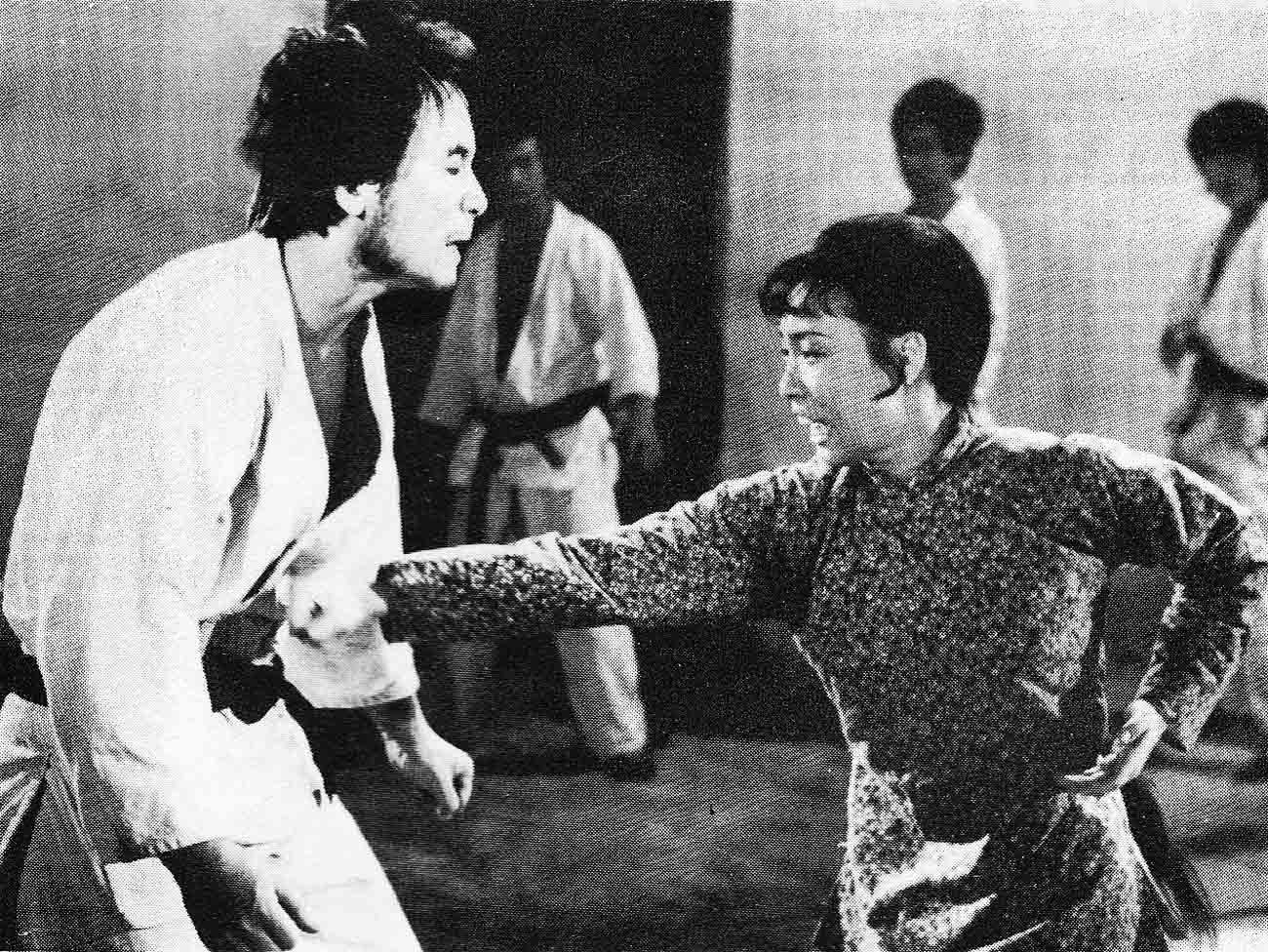

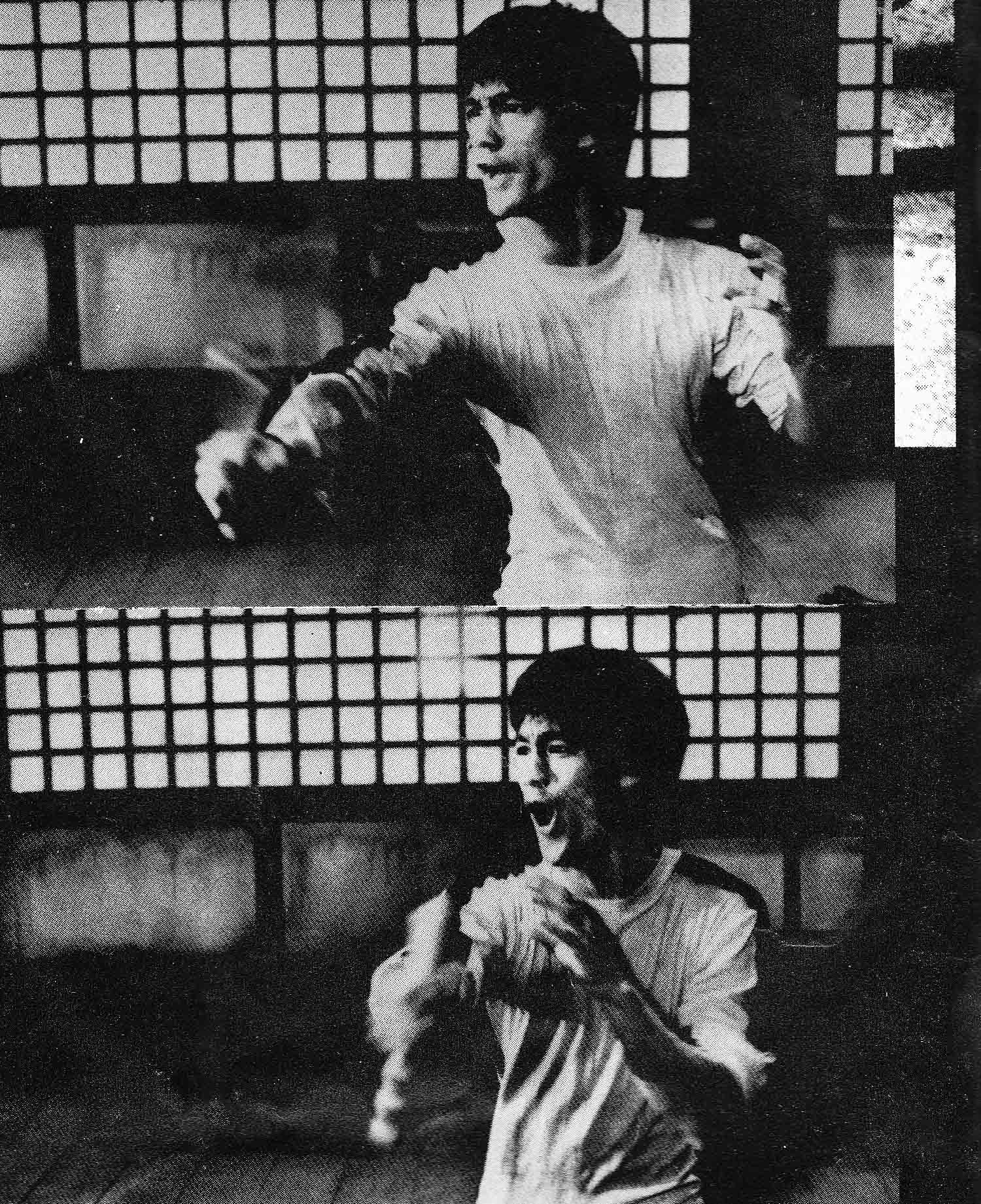

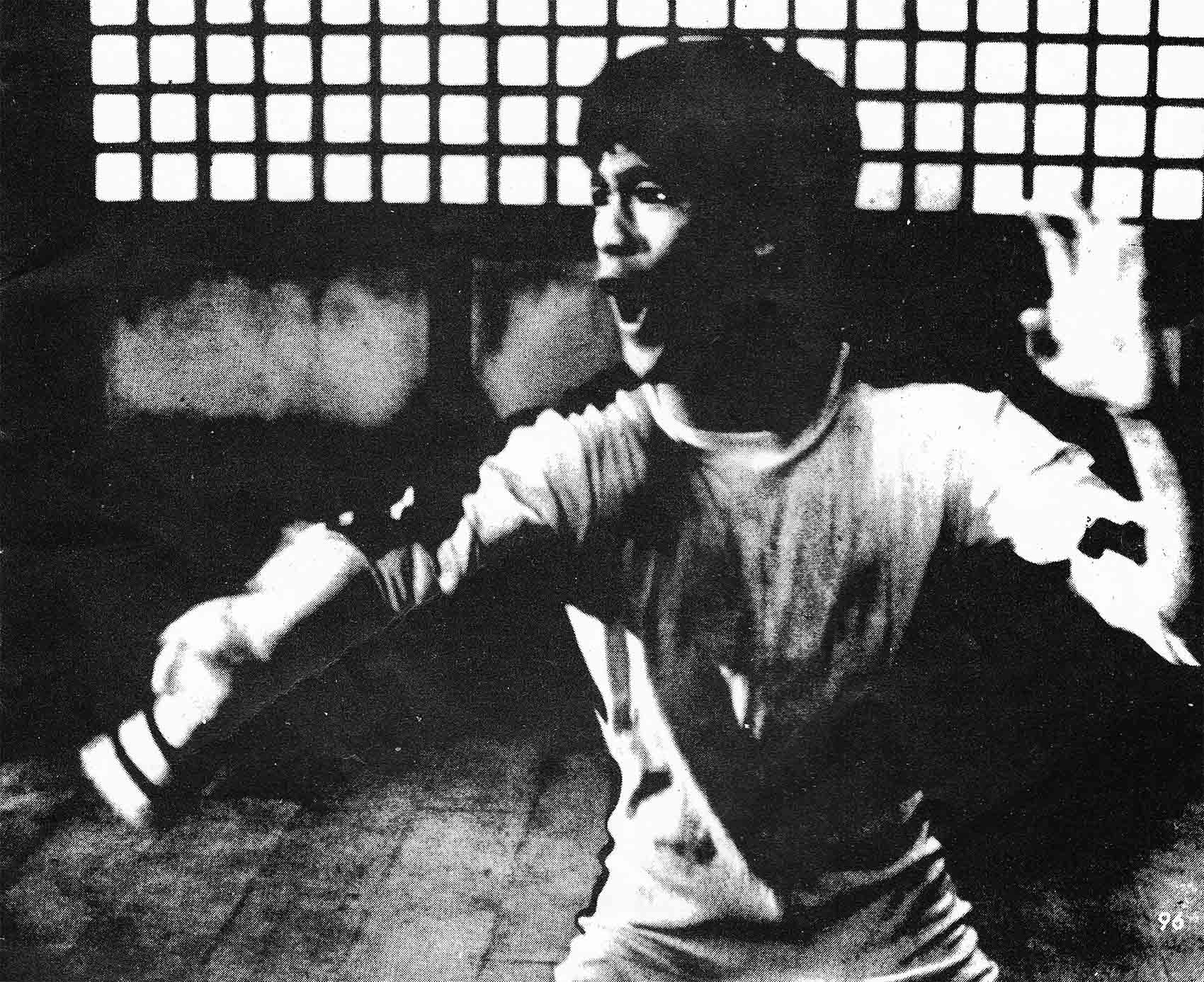

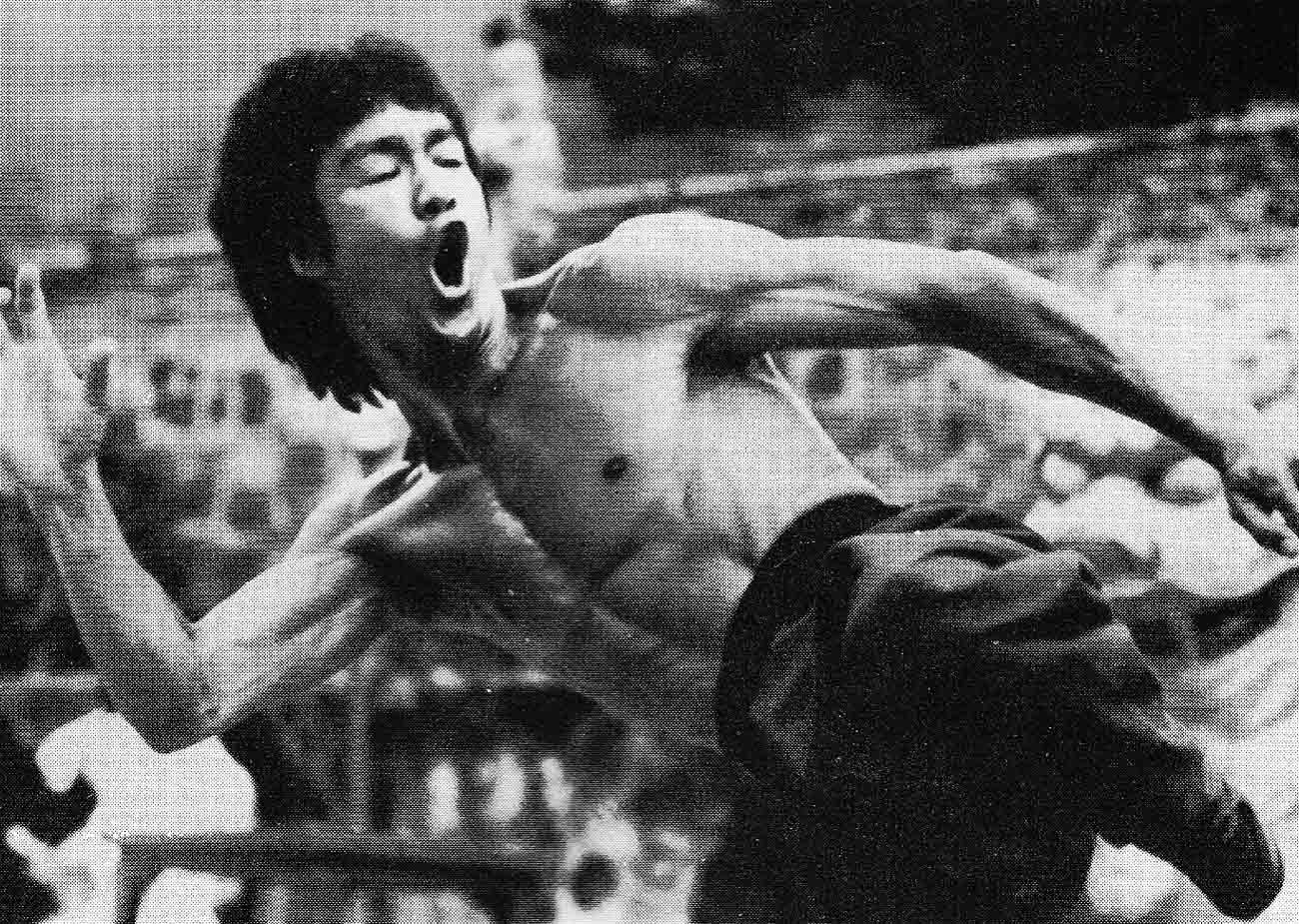

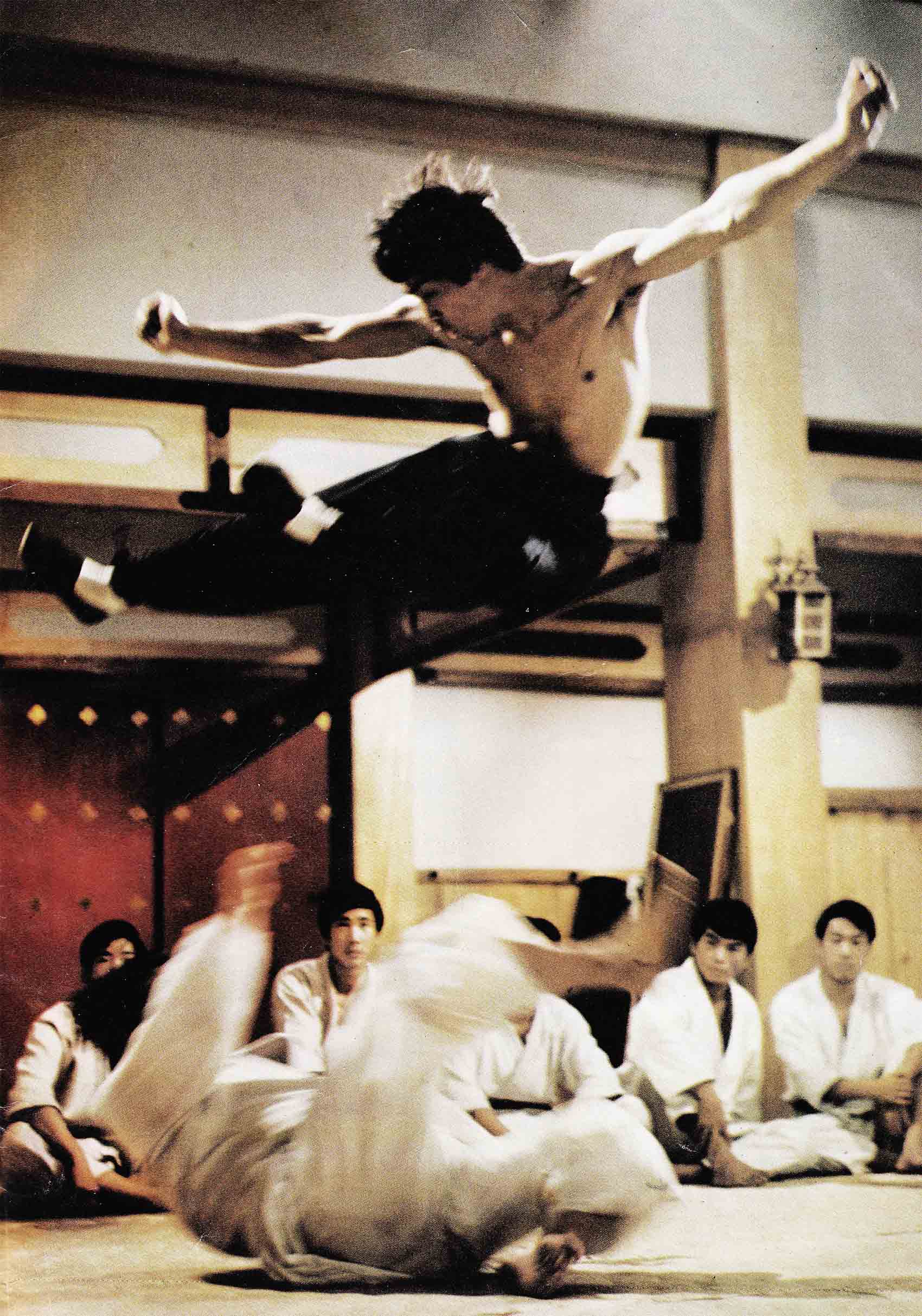

In time, Bruce and Danny had worked out the basis of the escrima bout. The sequence starts off with the escrima putting one of Bruce’s allies out of action. After he is dragged from the floor, Bruce and Danny get down to it. Three weapons are used during the episode. First up, the escrima chooses the double sticks and Bruce a Chinese bako, a thin whip-like staff of bamboo. Using the bako, Bruce disarms the escrima, who then picks up the nan-chukkas. Bruce follows suit and the two fight a nanchukka duel to the death. By all accounts the entire episode—titled ‘The Temple of the Tiger’—equals any battle Bruce Lee ever filmed. As a tribute to the escrima’s courage and martial skill, Lee lets him die a hero.

As many of Lee’s associates have also mentioned, Inosanto noted that Bruce was, above all else, a perfectionist. During both rehearsals and final takes he demanded total attention from his actors. When he was given it, he would create scenes at a furious pace, always getting the best out of the people and material at hand. “Bruce was an expert with material for his films,” Inosanto recalled after the Little Dragon’s death. “Especially in the fight scenes. He could develop it for people who did not know how to fight. Bruce made everyone look good. For those of us who were martial artists, he had a challenge—to make us all look even better. And he always succeeded.”

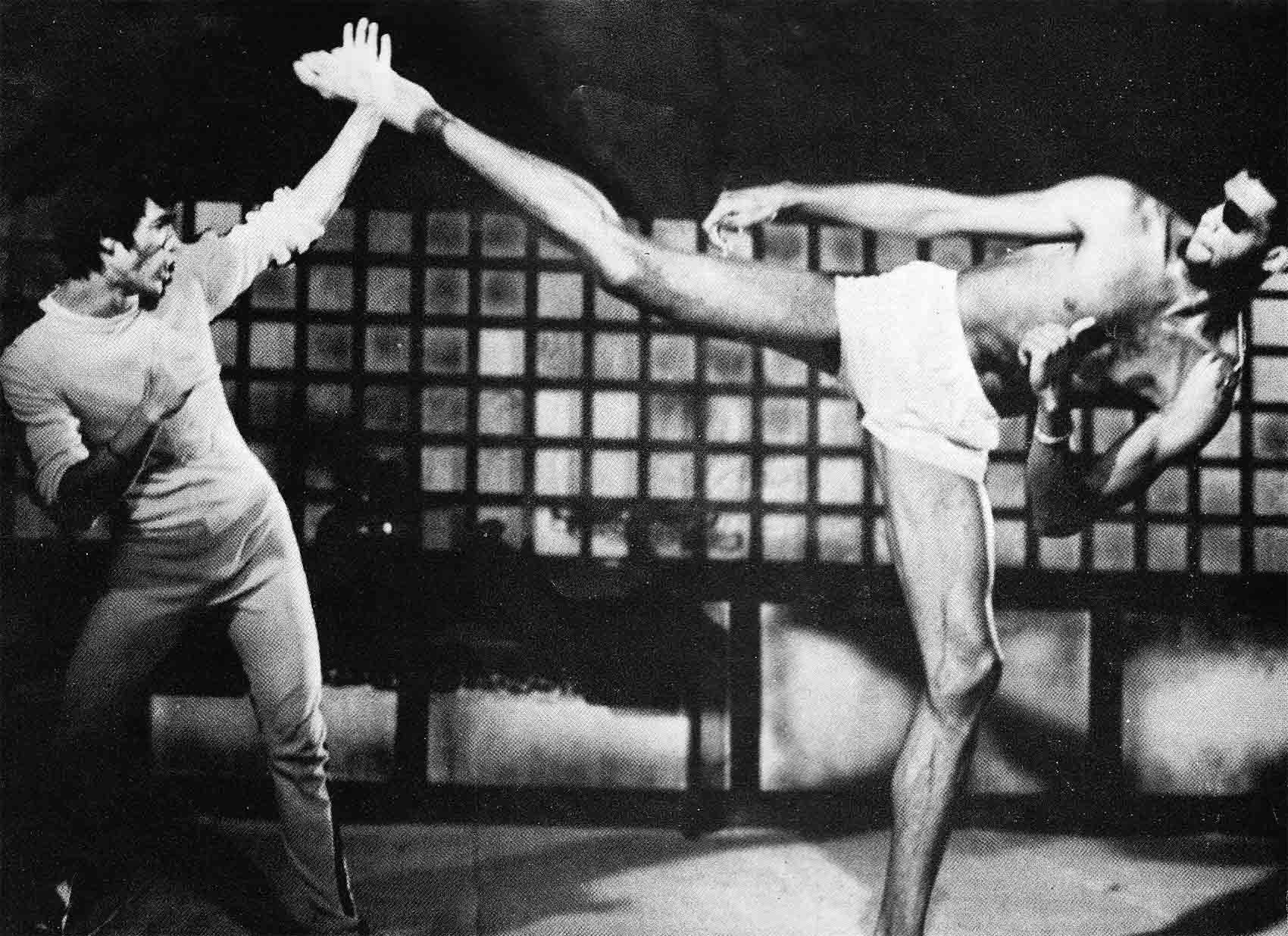

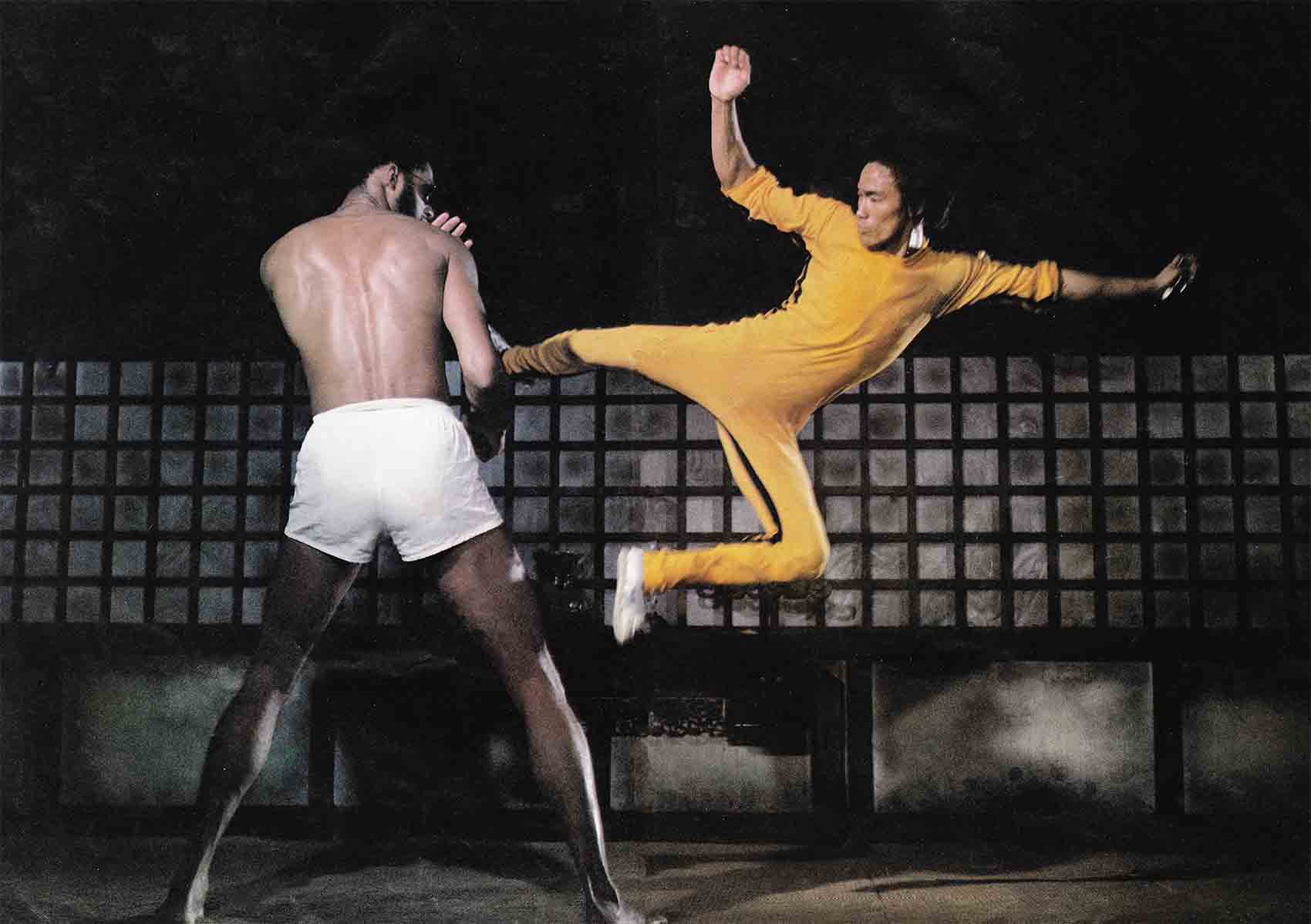

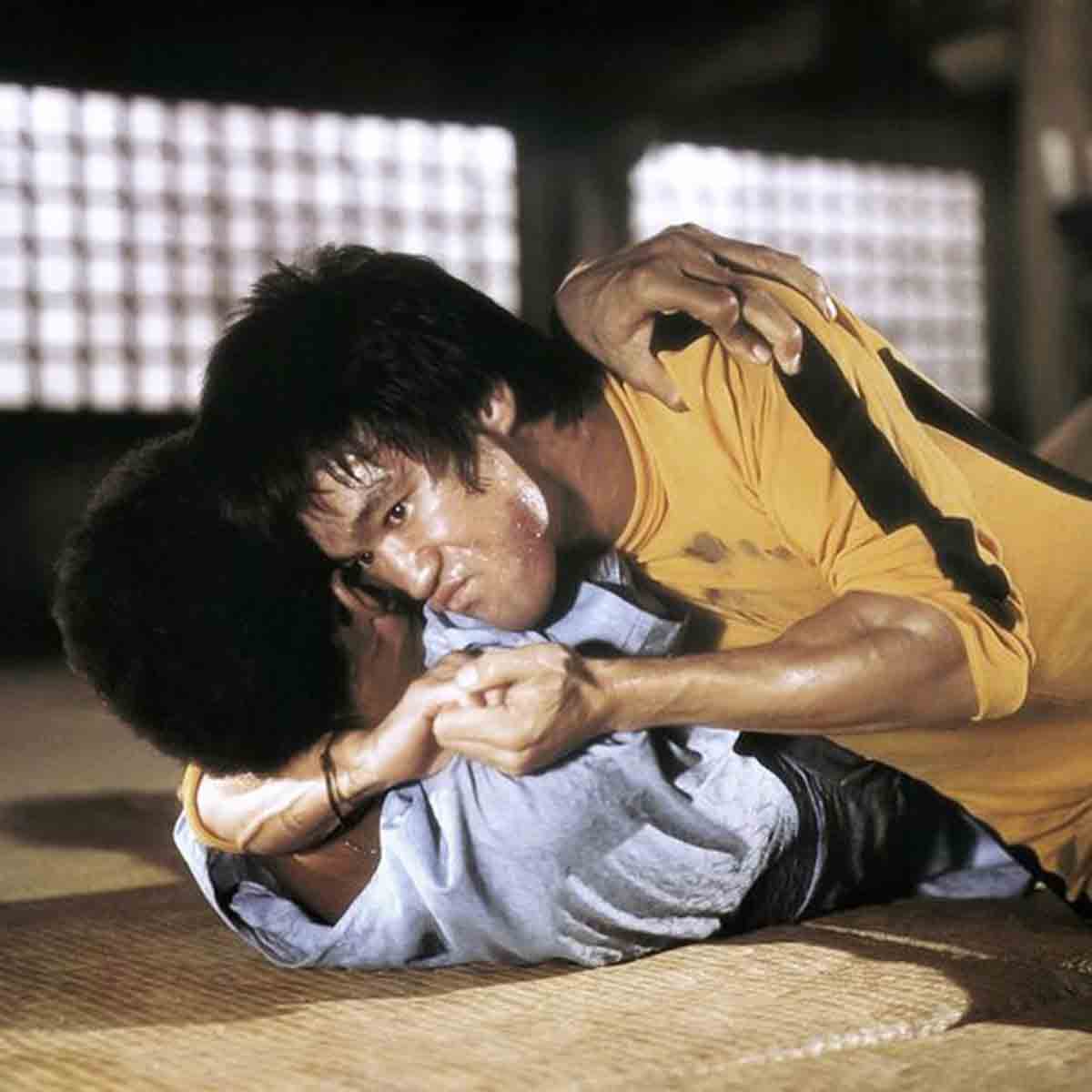

Apparently Kareem Abdul-Jabbar found working under Bruce Lee equally stimulating and rewarding. Although a novice at the martial arts, he and Bruce devised a sequence—titled ‘The Temple of the Unknown’—which promises to be as breath-taking as it is bizarre. The sequence opens with Bruce and his last remaining ally bursting into the top floor of the pagoda to face Big Lew, the fighter of the unknown style. Big Lew defeats Bruce’s aide and hurls him to the floor below. Then these two extraordinary opponents begin their deadly combat. Stills from the film highlight just how bizarre the match is—when he kicks, Big Lew’s enormous foot scythes the air several feet above Bruce’s head! Bruce, of course, is the eventual victor.

These then, together with the hapkido sequence, were the three episodes completed before death intervened. Just how long they run for is still something of a mystery: Dan Inosanto remembers being told that a bare 28 minutes of footage was available. Sources in London claim that at least half the film was completed. When we travelled to Hong Kong, we were informed by a Golden Harvest representative that footage lasting longer than a whole film had been shot and that all that was needed to finish it for release was a series of linking sequences.

Whatever the case, the scenes Bruce did manage to capture on celluloid will be well worth seeing even if there are only 28 minutes worth of them. As Dan Inosanto said, when it came to producing action films, Bruce Lee was a genius!

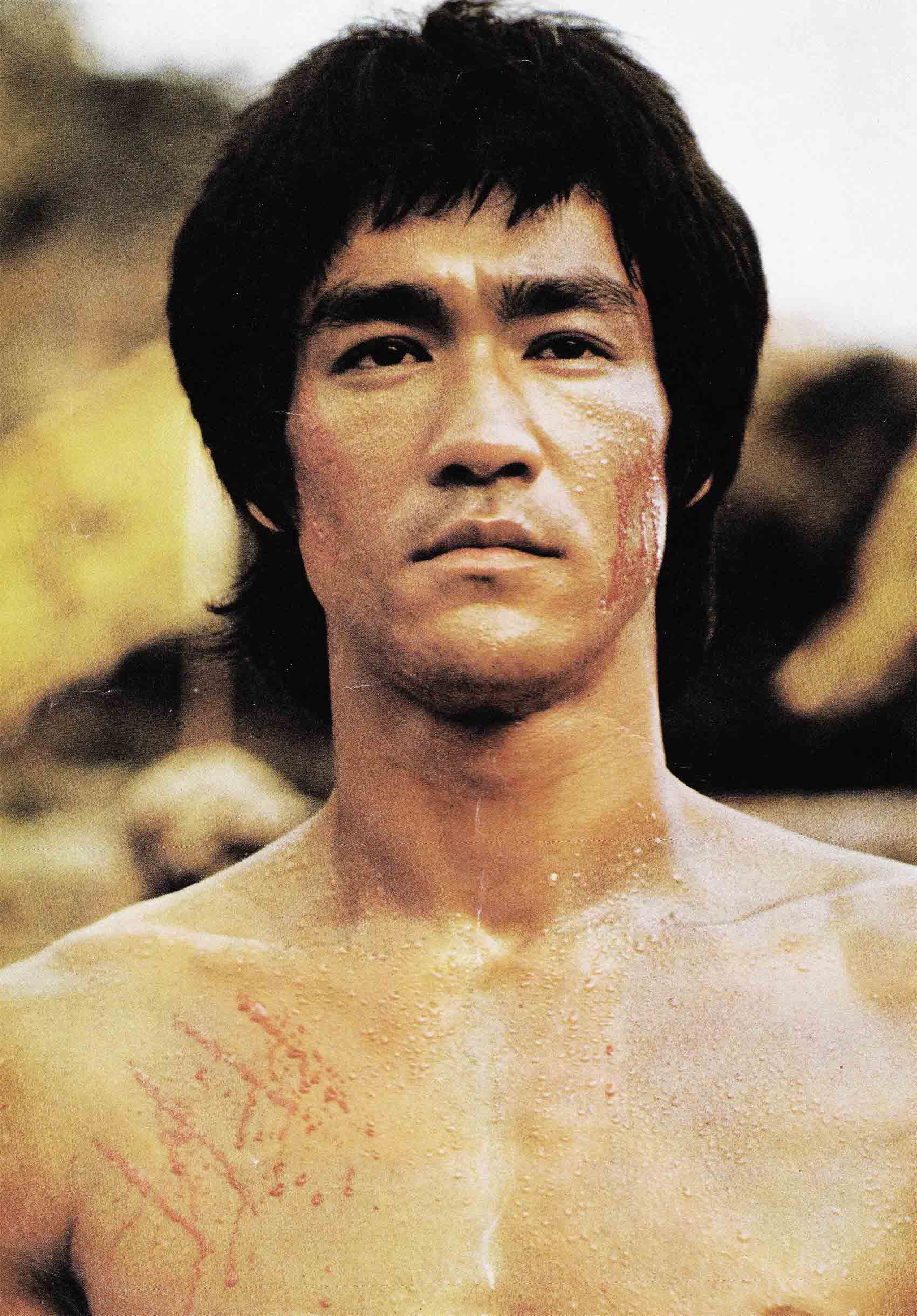

End of the Game

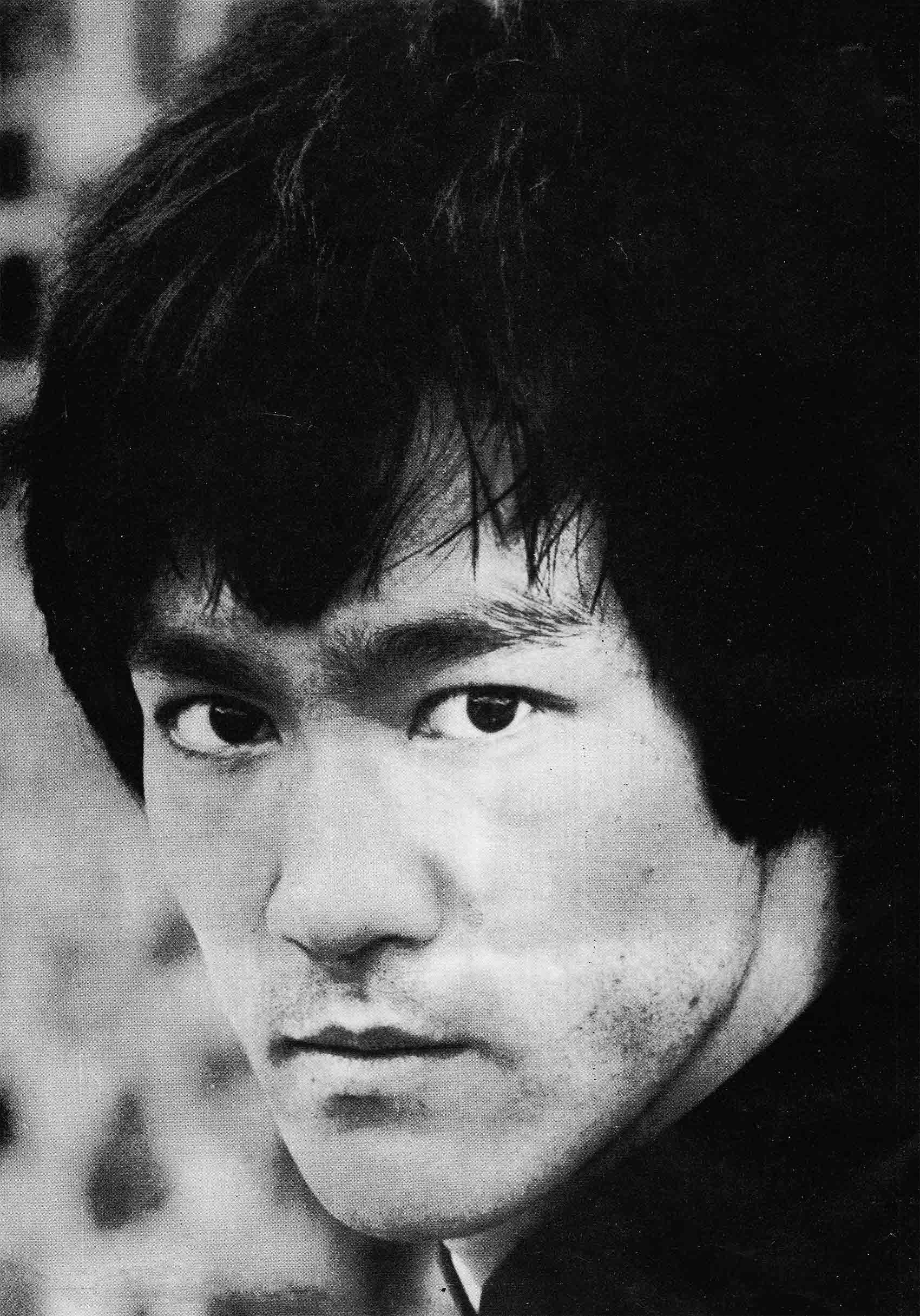

On the evening of July 20th 1973, Bruce Lee and Raymond Chow arrived at Betty Ting Pei’s Kowloon apartment. They were there to discuss Betty’s role in Game of Death. After many months, Enter the Dragonhad been given its final touches and was now waiting to go out on release. Bruce’s mind was now firmly fixed on picking up where he had left off on Game of Death. He was confident that, whereas his last solo film (Way of the Dragon) had been made really only for an Asian audience, Game of Death would prove to the world and Hong Kong film-makers in particular—that Chinese films could be made which would overwhelm both ends of the market—East and West.

A few days earlier George Lazenby had arrived in Hong Kong, and after the visit to Betty’s apartment, Bruce and Raymond Chow planned to have dinner with the Australian actor to discuss his role in Game of Death. Sometime during the course of the evening, Bruce complained of a headache. Betty told him to lie down and gave him a sleeping pill to help ease the pain. Before he fell asleep, Bruce told Raymond Chow to go on ahead to the restaurant and he would meet him later. In a few short hours, Bruce Lee was dead. Triggered by the sleeping pill poor Betty had given him, his brain had suffered a seizure—the second in a matter of months—and he had died without regaining consciousness.

When the news broke that Bruce Lee, the fittest man in the world, had died at the incredible age of 32, Hong Kong and the rest of the Far East could not believe its ears. One popular rumour which surfaced immediately and swept a dozen Eastern countries was that it was all just a publicity stunt cooked up to promote Game of Death. “The fans have been entering heated arguments over the issue and even placing bets,” reported one local newspaper. In time, however, an autopsy was conducted. An inquiry was held to halt the avalanche of rumours, intrigue and innuendo surrounding his death, and eventually a verdict was given: death by misadventure. Bruce Lee, it was decided, had been hypersensitive to the sleeping pill Betty had given him.

That was the clinical report. However, perhaps the cause of his death is more related to what his mother said when she heard the news: “Too much work.” Bruce’s wife Linda seems to support this theory in her recent biography of Bruce. In her book she says that Bruce had come to believe that the only relaxation he could enjoy was more work. “I know John Saxon took the view that Bruce’s life was just ‘spiralling away’,” she writes, “that he had reached a point where he no longer had a goal, that he was just going to go on without ever knowing how high he was going . . . The strain was there. And the moods were there. I saw his difficulties and I did my best not to add to the stress and strain.”

Perhaps it was the very perfectionism which Danny Inosanto and so many others noticed, the quest for perfection which kept Lee going at such a furious pace, that eventually burned him out and cut short his life at such a tragically young age. One after another he had churned out his films, going faster and faster each time. Perhaps Game of Death was the straw which broke the camel’s back.

One incident from this period stands out as an example of the pressures Lee was undergoing having jumped from Enter the Dragon straight back into the thick of Game of Death. Ever since The Big Boss, Lee and director Lo Wei had been engaged in a running feud centering on artistic and ego differences. Just a few weeks before his death, Bruce arrived at the Golden Harvest studio to run through the Game of Death plot with Raymond Chow. Learning that Lo Wei was in a nearby screening room, Lee suddenly erupted and rushed in to tell the startled director what he thought of him. The matter was not resolved until the police had been called and Bruce had signed a slip of paper promising in writing to leave Lo Wei alone.

Besides providing incredible work pressures on Bruce, Game of Death was also blamed in a more straightforward fashion by the Chinese community for Bruce’s death. The Chinese have a long tradition of superstitious belief—known as Fung Shui—and the film’s title was, to the Chinese fans, an obvious bad luck symbol. It was reported that when the title was first thought of, Lo Wei, recalling a top Chinese actor who had died in a car crash ten years previously after filming a movie titled Rendezvous with Death, warned that Game of Death was tempting fate.

The Future

With the grief and controversy over Lee’s death raging throughout the Far East, Game of Death was somehow lost ip the uproar. For months it lay forgotten in the Golden Harvest archives while the world debated the facts surrounding Lee’s tragic demise. For any other actor, death would spell the end of big box office pulling power. But with Lee, it acted in the reverse: overnight he crossed the line from millionaire actor to mysterious legend. Throughout the West the lines outside the cinemas swelled to their largest ever. The Bruce Lee cult had begun.

With such extraordinary public appeal being generated by Bruce’s movies both at home and abroad, it was, naturally enough, not long before Raymond Chow began thinking about releasing Game of Death. What with fans packing out showings of Marlowe, a B-grade Hollywood detective story starring James Garner in which Lee appeared for about five short minutes as an oriental villain, Chow must certainly have realised that a ‘new Bruce Lee film’, even if it contained only 28 minutes of Bruce himself, would have caused a sensation. However, Game of Death remained on the shelf. Indeed, it-was to be a full three years before the threads were finally taken up once again.

There are a number of reasons why Game of Death was neglected for so long. According to several sources in Hong Kong, the main stumbling block for many months was the name of the film itself. Linda Lee objected—quite understandably—to the inclusion of the word ‘death’ in the title. Raymond Chow, on the other hand, was convinced that, from a business point of view, Game of Death was the only title that was acceptable. Game of Death was what the fans knew. It was what they were expecting. Any other title would have caused confusion. Chow was even more convinced as to the validity of his argument when a sudden spate of ‘Bruce Lee’ imitations began to flood the market. Using doubles, these films purported to tell Lee’s life story, usually through a mixture of innuendo and tired old gossip. But one of these imitations went one step further: titled Legend of Bruce Lee, it had a plot line remarkably similar to parts of the Game of Death script.

The film opens with the bogus Lee (played by a young actor from Taiwan named Li Roy Lung who has made a recent career out of portraying the Little Dragon) being ushered into a movie screening room by a man closely resembling Raymond Chow. On the screen is another film—obviously meant to be Game of Death. After much incomprehensible coming and going, Lung’s girlfriend (who is doubtless meant to be portraying Betty Ting Pei) is kidnapped. Lung changes into a yellow track suit (!) and learns she is being held on the top floor of a pagoda. It is up to Lung to battle his way up each floor to rescue her. One of his opponents just happens to be a very tall black American! With this sort of rip-off film doing the rounds, it must have been an obvious fact in the Golden Harvest boardroom that Game of Death under any other title may very well have been lost in the flood of cheap imitations.

According to American rumours, another stumbling block to the film’s early release was Linda’s desire to complete her own film biography of Bruce. However, it is difficult to imagine that Bruce’s widow would contemplate holding up the film if it could possibly be completed and released. A much more powerful reason is contained in Linda’s book describing her life with Bruce. In the book she states that, before any moves are made, the problems associated with shooting a large part of the movie without Bruce appearing must be overcome. As it stands now, only the fight scenes have been completed. This means that a whole connecting plot must be constructed linking the scenes—all without the Little Dragon. There have been a number of suggestions aimed at surmounting the problem. A double of Bruce could be used (although this seems a very unsatisfactory way of getting around it; after all, Bruce Lee’s face is one of the most famous in the world, and to ask an audience to forget who it is they are looking at one moment and then to show them the real thing the next would appear to be stretching reactions to the extreme). Another suggestion is that Bruce’s action sequences could be used as the flashbacks in the mind of another, entirely new, hero.

If a double is to be used, one likely candidate for the role is a young martial artist by the name of Alex Kwon. First Artists, the Hollywood production company handling Linda Lee’s Tribute to Bruce Lee, spent weeks auditioning martial artists hopeful of stepping into the Little Dragon’s celluloid shoes. Unfortunately, no-one could be found to fit the bill. By chance, an editor of a leading American martial arts magazine spotted up-and-coming Kung-Fu competitor Alex Kwon wandering through his office one day. The editor was so struck by Kwon’s resemblance to Lee that he forwarded him to Hollywood post haste. After throwing the right punches and pulling the proper faces, Kwon was hired. By fortunate coincidence, Kwon’s style of martial art—known as my jong law horn—is similar to jeet kune do in that it is extremely fluid. Even though Tribute to Bruce Lee has not yet gone into production (it is scheduled for spring shooting), Alex Kwon is already making an impression on the Hollywood backlots. Steve McQueen, who saw Alex work out for his screen test, claims the young martial artist bears an “uncanny” resemblance to the Little Dragon.

As things stand now, the first steps are now being taken to pull Game of Death back into production. As one Golden Harvest spokesman told us in Hong Kong, four scripts have been prepared and submitted to Raymond Chow. If Chow likes one of the four, it will provide the basis for linking Bruce’s fight scenes and tying them in to a complete movie. If he rejects them all, a new script will be speedily written by one of the Californian script writers who have been approached by Golden Harvest over the past few weeks. Perhaps sometime in April shooting will commence. Perhaps sometime in autumn, Game of Death will be complete.

In Hong Kong recently, a Golden Harvest executive, when asked the reason for the three year delay in reshooting Game of Death, paused for a moment and then answered that, although there were other factors, perhaps the biggest reason was that the company felt everything had to be done just right. It was Bruce Lee’s last testament, he said, and it had to be re-made exactly as he would have wished it. Anything less than perfection would be unforgiveable. Soon the waiting will be over and Game of Death, the most fascinating film in recent years, will flash onto cinema screens around the globe. Let’s just pray that it is a legacy worthy of the most extraordinary man of our time . . . Bruce Lee, Little Dragon.

It is a quote. KUNG-FU MONTHLY MAGAZINE

No Comments