Barbara Stanwyck: “I Never Had A Doll”

I don’t remember them at all.

Catherine, my lovely Irish mother, died when I was two and my English father, Byron Stevens, just up and disappeared soon after. He had loved my mother madly, and when she died he went gypsy; working—when he worked—as a laborer.

Millie, my youngest sister, took on most of the responsibility of looking after me. She managed, through some miracle of ingenuity, to stretch her skimpy chorus-girl wages to pay for my room and board with various families in Brooklyn.

In the environment in which I grew up, kids existed on the very brink of domestic or financial disaster. We were alert, precocious and savage. I endured this world by developing a bitter hatred of it, which I made no effort to conceal, and by retreating to a dream world of my own.

One blistering afternoon I was hanging around on the sidewalk watching a group of boys lazily playing catch in the street. I heard a kind of hissing sound and there was a dirty-faced brat shaking her finger at me. “She’s a orphan!” she yelled. The kids ringed around me, a stealthy, menacing, yelling mob, jumping up and down and chanting: “Yas, yah, yah! Orphant, orphant, orphant!” I gritted my teeth, salt stinging my eyes. I stared them down as long as I could keep the tears from spilling. I hid for the rest of the afternoon in the darkest hallway I could find.

On Sunday afternoons, sometimes, Millie would take me to a movie. Pearl White serials, The Perils Of Pauline, The Exploits Of Elaine, were my passion.

From these sessions with dazzling adventure in hot and stuffy neighborhood theatres, I emerged, no longer Ruby Stevens, the orphan drab and desolate, but the counterpart of my idol.

In all my life, in all the parts I’ve played, I have never forgotten Pearl White. I’m bedeviled by the urgency, whenever one of my pictures has any kind of a stunt scene, not to have a double. True, the double is hired and gets her check but I have to ride over that cliff or under that waterfall or run through that burning building or scream through that train wreck—all in the best tradition of my intrepid Pearl.

The Reverend William Carter, Pastor of the little Dutch Reformed Church in Flatbush, always smiled at me whenever I walked by, and one day, he spoke to me. He asked me if I’d ever been baptized. I told him no, and he looked so sorrowful that I asked him to baptize me. I’ve always kept the New Testament Reverend Carter gave to me on my twelfth birthday.

Whenever Millie took me backstage for a Saturday matinee at whatever theatre she was working, I stood in the wings, promising myself, passionately, that I would, someday, be a great dancer—another Isadora Duncan!

When I was thirteen, I got a job as a clerk for the telephone company and got myself fired almost as soon as I was hired. An irate subscriber confronted me with a mistake in her bill. Where I came from—somebody yelled at you, you yelled back louder. I was out of my job in nothing flat.

I trudged from one place to another, in answer to every likely ad in the help-wanted columns and finally landed in the pattern department of Condé Nast.

One day a lady came to me for instructions in cutting some expensive material to the pattern I’d sold her. With the superb authority of utter stupidity, I gave her explicit directions. The lady trustingly followed them.

The management struck me from the payroll. This time, I bounced happily down the stairs. Now I knew where I was going. Show business. That was my business! As for trying to be anything but a dancer, I’d had it.

Confidence and the example of an indomitable serial queen are ripe assets in a teenster. I was fifteen—a statistic to be denied. I went winging my way in and out of casting offices, my hair plastered in “dips,” mouth painted, eyes heavily, un-skilfully outlined, my lashes loaded with mascara. I’m sure the man who hired line dancers for the Strand Roof knew how young and green I was, but he hired me.

I was a hoofer!

In my sole compatibility with the neighborhood kids, I had danced for “hat money”—small change tossed by passersby. The ruthlessness I’d developed as a part of my survival equipment, because my fists were as important as my feet in getting my share of the tossed coins, was priceless.

When the Strand Roof closed, I shuttled from one chorus job to another. I loved going through the battered stage doors. I loved the scramble for places before curtain time; the music, the excitement, the color. I even loved the hazards. I didn’t panic when I was broke between jobs, and like the rest of us hoofers, acted filthy rich when I had any salary coming in.

Between jobs, we all shared one precious resource. That was Billy LaHiff, our father confessor; Mr. LaHiff, my Good Samaritan. He owned The Tavern on 48th Street and a heart as big as a circus tent. He never refused a meal to a hungry chorine nor to an out-of-work actor. And he had no memory at all for what you owed him if your luck was slow.

Mae Clarke; Wanda Mansfield and I shared a cold-water, walk-up room. We were short on cash and tall on dreams in our “Three Musketeer” relationship. If one got a job we all ate; if we were all “at liberty” we shared our lack of resources just as thoroughly. We laughed a lot and kept worry a stranger.

One night Billy LaHiff collared me and said, “Ruby, I think I can get you a job. Willard Mack’s casting—looking for a chorus girl. Come meet him.”

Willard Mack! A top “legit” producer, actor, playwright, director. I was not awed. Legit had little to do with my beloved branch of show business.

Mr. LaHiff said, “Name’s Ruby Stevens, Bill. Helluva little hoofer—sweet pair o’ gams, too.” Mr. Mack said, after giving me a sharp-eyed inspection, that, yes, I could have the chorine bit in The Noose. “There are three of us hoofers, Mr. Mack,” I said. “I don’t accept any job except it’s one for all of us.”

Wrinkles of amusement splashed the corners of his eyes. “All right, Ruby,” he said, “bring your friends.”

The tryout of The Noose in Philadelphia was as dreary as a wake. It was a turkey. Mr. Mack went to work again. He rewrote, re-cast and rehearsed, rehearsed, rehearsed. When he changed the story, he became possessed of the conviction that Ruby Stevens could be trained into an actress! I was never so shocked in my whole life. I felt like Pearl White, in a real big peril. But by now, I kept my mouth shut when Mr. Mack gave any orders.

Day and night he drilled, drilled, drilled me to play one of the most poignant dramatic roles he ever wrote. After a week made up of days and nights of endless work, work, work, it was again curtain time for The Noose. In Pittsburgh.

When the curtain fell on that second performance everyone was ecstatic. Except me. I was just lightheaded—from no sleep and gallons and gallons of coffee and skipped meals. But, taking my first bow, I was lighthearted. If the applause was to be trusted, I hadn’t let Mr. Mack down.

We tried out for three more weeks on the road. Then we went to New York for pre-Broadway rehearsals at the Belasco. We were all in the green room when Mr. Mack arrived. He walked over to me and said, “Ruby Stevens is no name for a star.” He glanced around the room. The walls were lined with framed programs. One read, “Jane Stanwyck in Barbara Fritchie.” Mr. Mack turned, held out his hand, “Hello, Barbara Stanwyck,” he said.

That’s what became of Ruby Stevens, who was going to be a dancer.

Nothing was the same after that. Mr. Mack introduced me to a world I entered resistlessly only because this great and kind man had staked his reputation on my performance. I lived, ate, slept, dreamed the part I had to play. Most of the time I was too tired to breathe.

I did get a wire off to my sisters in Brooklyn telling them I had an important part and that there would be tickets for them at the box office opening night. The Noose was a hit. I was besprinkled with the lavish excitement of a Broadway first night. Everyone else had friends and family galore backstage after the performance. Mr. Mack introduced me to lots of people but I kept watching for my sisters. Finally, when the crowd was all gone and only the eerie work lights were left on the stage, I gave up, took my make-up off and got to a telephone booth.

Well, they’d been at the theatre all right. They’d had fine seats, right down in front; they looked through the program, didn’t see my name and when I didn’t come on in the first act, they decided there was a mistake somewhere and went home.

I had forgotten to tell them I was Barbara Stanwyck.

The Noose ran for nearly a year on Broadway. Mr. Mack continued to coach me—to teach me what acting was all about. It was a lonely, concentrated, consecrated life. He made me learn a new play every week. He drilled me as carefully in each week’s role as though I were going to open in it on Broadway. No one ever had so great a gift from so great a master. Willard Mack was theatre. Acting was his religion. It became mine.

I still missed Wanda and Mae, remembering our zany laughter whether we were in or out of jobs. In the midst of being a successful dramatic star on Broadway, I’d wonder, when I had any time at all to do anything except study the endless scripts Mr. Mack assigned me, what would have happened to Ruby Stevens if Billy LaHiff hadn’t decided to get her a job.

She was a kid who never had been a child, really. Now she didn’t exist at all.

One night Oscar Levant brought a friend to my dressingroom. Loving show business, I worshiped at the shrine of talent. I’d seen Frank Fay in his incomparable performances time and again at the Palace Theatre. He had, also, indisputably irresistible personal charm.

I met him. I loved him, I married him.

I came with him to California.

I lacked the social ease which those who have always been welcome wherever they go wear as gracefully and casually as a model wears a mink coat, and our life was a series of glamorous parties where I sat in the corner attracting no more attention than the furniture. Listening to all the bright, easy, sophisticated conversation, watching Frank sprinkle his magic over everything, watching the women glow under the spell of his charm, watching Frank, gay and happy and unaware of me until going-home-time.

I polished the chip on my shoulder. I pasted a smile on my face. I hated everything but the hours I had with Frank alone. As these grew fewer I grew more silent. If I kept very quiet I could hear all the lovely, happy chatter of my dream-world people.

True, I was in Hollywood as Mrs. Fay, but as nothing in my background had fitted me to fill the endless hours of Mr. Fay’s. absence from the hearthside, I thought I ought to put Mr. Mack’s teachings to practical use. I got an agent.

I made test after test—nine of them, by actual count. Each and all were deplorably unproductive.

One day a young director—his name was Frank Capra—sent for me. “I think you’d be great for this part. I’d like to make a test,” he said. Bitterness overwhelmed me. Poker-faced, I walked to the door.

“No, thanks,” I said, holding tight to the doorknob, hoping my trembling didn’t show. “I’ve had some.” I started out.

“Take it easy, Barbara,” Capra spoke, real quiet. I stopped. I looked back.

Capra was grinning. He said, “Report for wardrobe, nine o’clock Monday. Our picture is Ladies Of Leisure. I’ve got faith in it—I’ve got faith in you, too.”

That faith and Ladies Of Leisure changed my life in Hollywood. It also established Capra as a director of the first magnitude. Now I was a girl named Stanwyck—who had a hit picture. That’s the nicest friend a girl can have in Hollywood.

Just as my marriage to Frank Fay was inevitable, so, I guess, was our parting after seven years. We were divorced in 1936.

Once again, I knew the world was alien and unfriendly and I didn’t want to know any different. The chip on my shoulder held my shoulders straight and my chin up and my eyes were curtained so that no one would know I didn’t believe in anything in the world.

Marian and Zeppo Marx refused to be snubbed by my indifference. Hepped on the idea of establishing a horse breeding business in the Valley, they urged me to join them. I found myself co-owner of Marwyck Ranch, as incongruous a bit of self-casting as I’ve ever heard of!

They built their house on one hill—I built mine on one adjoining. I built the swimming pool, they the tennis court—both of which we shared. The stables spread across the land beneath our houses. When all the building was done I had no interest in any of it. I sat in my house on that hilltop looking through eyes clouded with the bitterness inside me, across the acres which were half mine. I knew it was a far cry from the Brooklyn tenements. I knew there was beauty in my home. There was no beauty in me. I was still a bitter child cowering in a dark hallway.

Zeppo and Marian persisted in saying they wanted me to meet a man whose name, I gathered, was Artique. They insisted I’d like him. Finally, I gave in and said I’d go to dinner with them at the Trocadero.

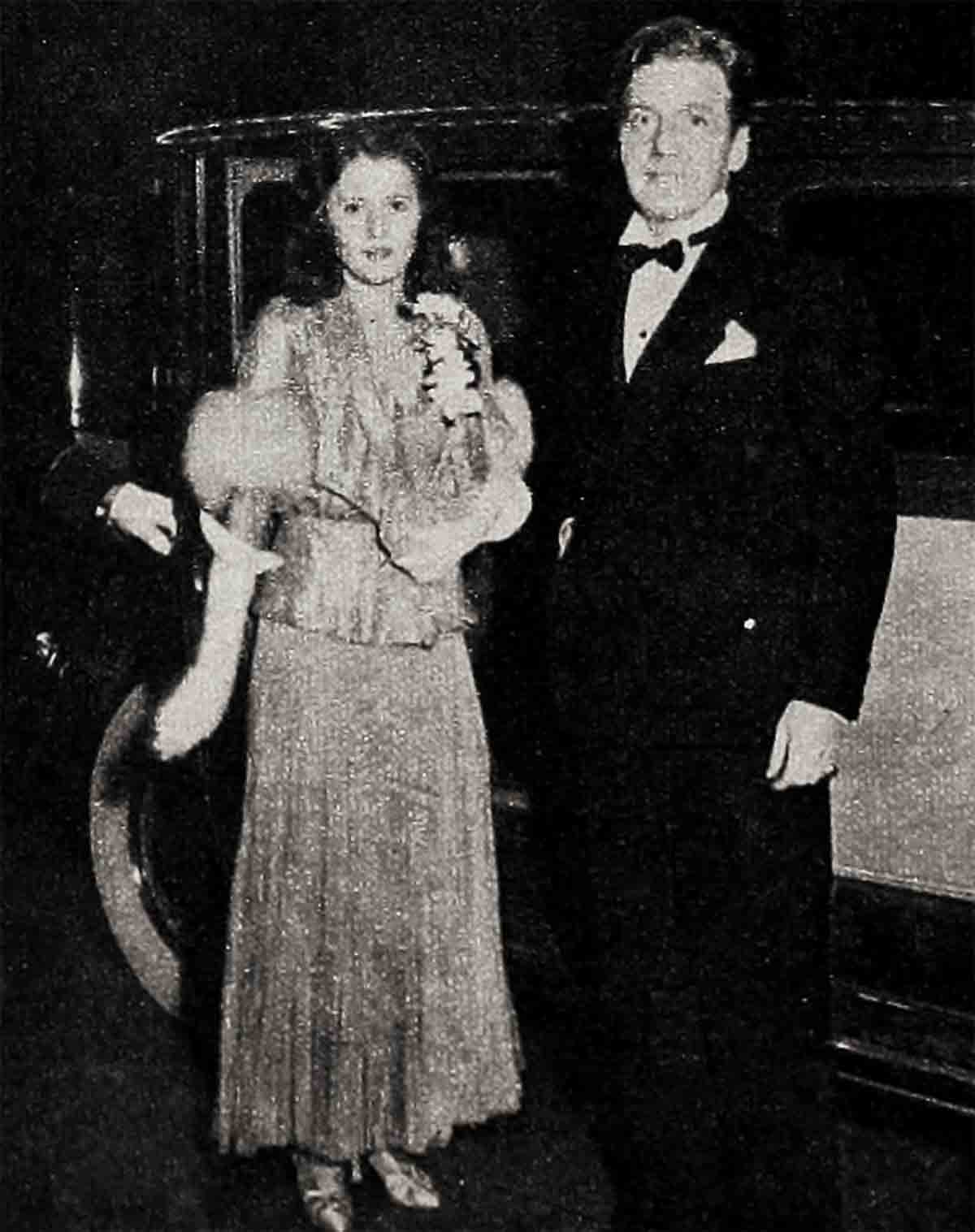

A young man who was the latest motion picture box-office rage, was sitting at our table. I was introduced to Robert Taylor.

We made polite conversation, while I wondered what had happened to my “date.” Then I confided, “I was supposed to meet a Mr. Artique here tonight.”

Taylor’s blue eyes twinkled like crazy; he grinned that famous grin, and gave with the warmest chuckle I ever heard. He murmured, “R.T., Ma’am, R.T. That’s the one you were to meet, and—I am he!”

It was okay with me. Marian and Zeppo were right. I did like Robert Taylor.

For the next three years, R.T., my friend, held an absorbing place in my thoughts and absorbed most of my time. We were not, we protested publicly and to each other, in love; we simply and frankly enjoyed being together.

Bob had to go to England to make A Yank At Oxford. When he returned, the old, good-companion relationship, the camaraderie that had been so rewarding, just wasn’t there any more. We were possessed of an awareness of each other that made mere friendship impossible.

On May 13, 1939, we drove to San Diego with Zeppo and Marian and Ida Koverman and we were married by a Justice of the Peace at one minute after midnight. The Little People made pretty music in my secret world.

No sooner was the dream house we built a long-awaited reality, than Navy Lieutenant Robert Taylor left for duty.

The loneliness of waiting for the lieutenant’s return was not like any other loneliness because I shared it as a member of an enormous family which stretched across the world. It was a family made up only of women—and men too old or too young to leave us. In this loneliness no wife was really alone; millions of wives endured the living in a state of suspense—of suspended animation—thinking life would resume, at the war’s end, exactly as it was before. Eventually, it was over. Eventually, our men came home—those who could come home, I mean.

Soon after Bob’s return he got his own plane and flew all over the country on fishing and hunting expeditions. One long location trip after another took him away, too. To England, Italy, Utah, New Mexico—we were weeks apart after years apart. Ten days before Christmas of the year 1950, we called Helen Ferguson and told her to prepare our divorce announcement for the papers.

I bought a new house, sold our house, and every stick of its furniture. Wandering through those empty rooms a wracking bitterness held me.

I started down the stairs. A sort of blackness enveloped me.

When I opened my eyes, Helen was leaning over me and the doctor was there. I said, “I’ve lost my husband.” As though that explained everything. I expected her to comfort me. But, her face stern, she said, “What makes you so proud of that? It’s a very commonplace accomplishment.”

I could have killed her.

I turned my head away. I wouldn’t look at her. She leaned close and said, in the softest whisper, “You’re the daughter I never had.” Helen has a mother-heart; only her lack of years disqualified her. I didn’t move or hear her leave. My world was filled with what she had whispered.

I’d been called “daughter.”

I wish I could say that from that moment I began to let all the kindnesses friends held out to me reach me. It would be a lie. I didn’t get rid of my bitterness. I went to parties dressed in my finest, and I talked with crackling bitterness—and too much. And I laughed a lot.

Then Nancy Sinatra planned a surprise party for my birthday. When I saw all the smiling, loving faces in her living room, I resented the invasion of my misery. But I made myself very gay.

I didn’t want to open the presents piled high at the end of the room. But they made me. So I exclaimed over all the generous and extravagant gifts and everyone smiled, rewarded, and I felt like a worm in a spotlight. I came to Helen’s gift. It was not extravagant. It was something she had written—something lettered on parchment, and it was in a little silver frame. It had a title, “A Prayer For Missy.”

Even before I finished reading it the dam inside me broke.

And now the tears were sweet and cleansing and I heard, with my heart, the tinkling sounds of the joy of my Little People. It was no strain to hear them, because there was no sound at all in Nancy Sinatra’s lovely room. It was filled with the waiting, understanding silence of people who loved me.

Part of the miracle was that I wasn’t embarrassed because I was crying.

In those tears, the death of my bitterness began. This was the start of my journey away from my childhood.

Next day, I showed “A Prayer For Missy” to Nana, (that’s what we call Helen’s mother). She smiled and I smiled and there was a glow about everything.

We were in Nana’s room. She was surrounded by dolls of all styles and sizes and piles of paper and she was wrapping each doll very carefully. I knew the dolls had belonged to her granddaughter.

“Nana,” I accused her, “aren’t you a little old to be playing with dolls?”

“I’m just loving them a little as I put them away.” She looked at me and said, “Never be ‘too old’ for anything, Bobbie.”

It is said of Nana by all who love her, that she talks in Braille, but we’ve learned she has a special way of telling us what she knows it is time for us to hear. Nana never bludgeons us with her wisdom. She offers it with a bright unexpectedness; with a soft delicacy.

So I was quiet, thinking. I watched her tender inspection of each doll before she hid it in the paper. Then she looked up and asked, “Didn’t you ever have a doll?”

“No,” I said.

“Ah,” said Nana. She looked again at the doll in her hands. Her face was sober.

“Well, it does take a lot longer to grow up without a doll.” That’s what Nana said.

Then she grinned at me, and we shared another secret. A peaceful secret.

That was three years ago.

Before I knew better, one of my proudest boasts was that I always prayed only for others. I still pray for others. But in all humility, I now pray for myself, too. And I know He listens. Nana taught me because her years are so many and her heart so young and trusting—not to be afraid to grow up. Nana’s example brought me to restored believing, to faith, to daily prayer; to gratefulness for the blessings I have had—and which I truly love to share. I have had so many of them. I’ve given a lot of lip-service to God, but now I know how to properly thank Him.

When bitterness goes, there’s plenty of room for a lot of nice things. Like—really wanting Bob and Ursula Taylor to be happy in their whole future together; like appreciating the things I receive, whether they are just exactly what I’ve asked for or not; like waking up in the morning knowing I’ve good hard work ahead of me at the studio, and friendly folk to help to do it; like laughing because I’m happy and not laughing at something or someone as a cover-up for disappointment and turmoil within me; like filling the hours I spend alone with hope instead of distrust; and like praying with confidence instead of being afraid to pray at all.

Last Christmas Helen gave me a doll. Tied to its hand was a card which said, “I belong to Ruby Stevens.”

I laughed and laughed until I cried!

I’m a big girl now!

THE END

—BY BARBARA STANWYCK

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE JUNE 1955