Robert Mitchum’s Way

A few months ago Robert Mitchum received what might be considered a surprising and flattering offer: a two-week engagement with Britain’s Stratford-on-Avon company, to play King Richard. Except that nothing surprises Mitch very much, and flattery will get you nowhere with him. Predictably, he declined the bid.

“Demmit, Bob,” said Charles Laughton, who was then directing him, “you ought to do it. It would be the first time they had a living, breathing actor in the role in quarter of a century!”

Mitch’s big shoulders shrugged lazily. “What would it prove? That I can do Shakespeare? For two weeks? I’d rather be a bum.”

Than an actor? “Than anything,” Robert corrected; he had already dismissed the honor, if such it was, and gone on to other things. “I’ve worked at just about everything a man can do to earn a living, and the longer I think about it, the more I’m convinced that I just don’t like to work.”

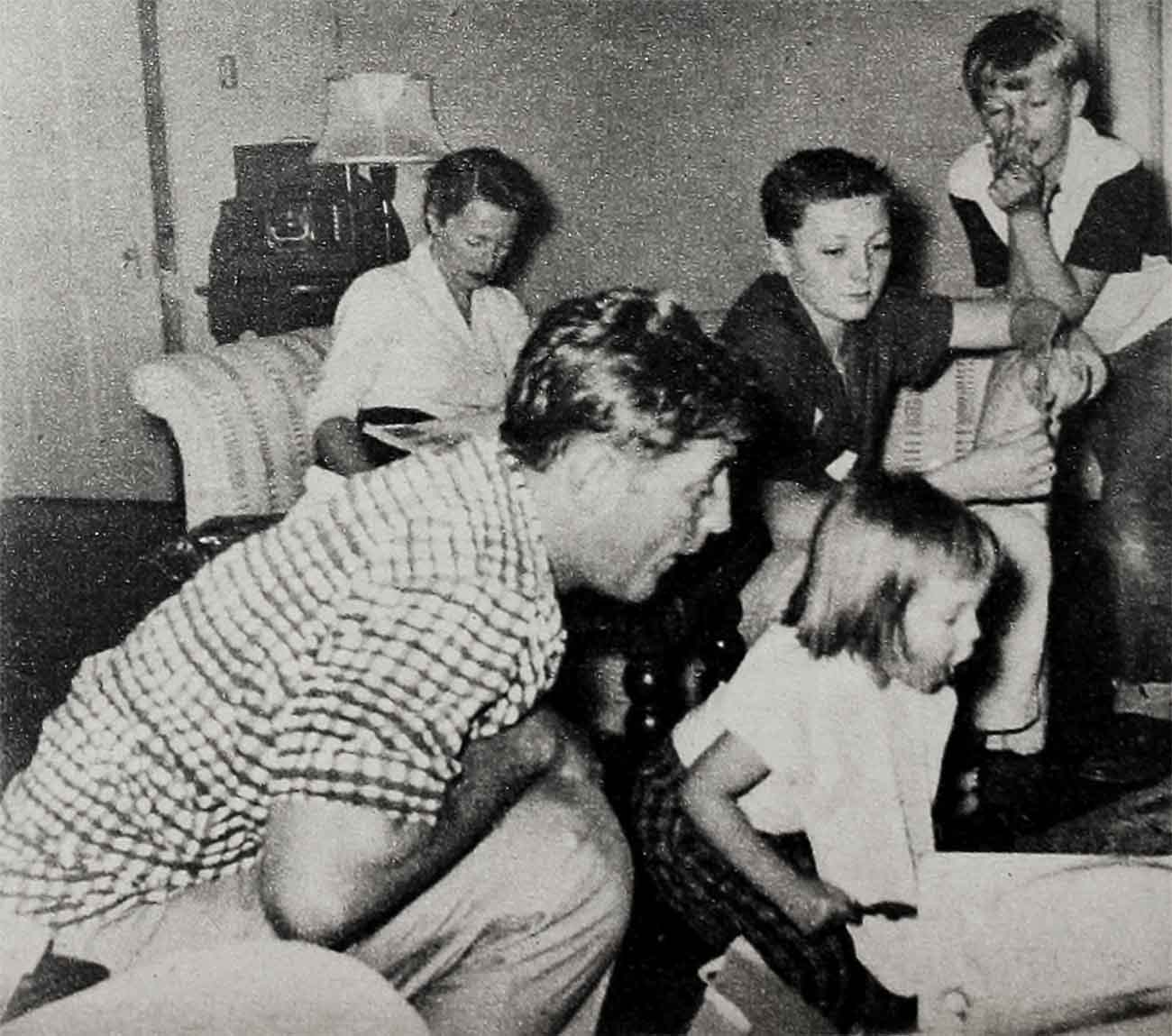

Yes, but you can’t not work when you have a wife and three children. Bob snorted derisively. “Look, I can be a bum and still make half a million dollars a year to take care of my family. Don’t you see? I am a bum. And I have nothing to prove, so why should I go to England to play Richard when I’d rather travel with my wife? . . . Besides, if I worked myself to death at acting, the same people would be saying I was wasting myself. No matter what I did, they’d still say it. Why bother, since being a bum is more natural?”

There are these people who believe Mitchum is an undeveloped genius. Like Mr. Laughton, who found nothing odd in the idea of his playing Shakespeare.

Like young Tab Hunter, who said in tones of pure hero-worship, “You have to work with him to know. Walking from the parking lot to the set he would learn whole scenes—and give a performance you could never forget.”

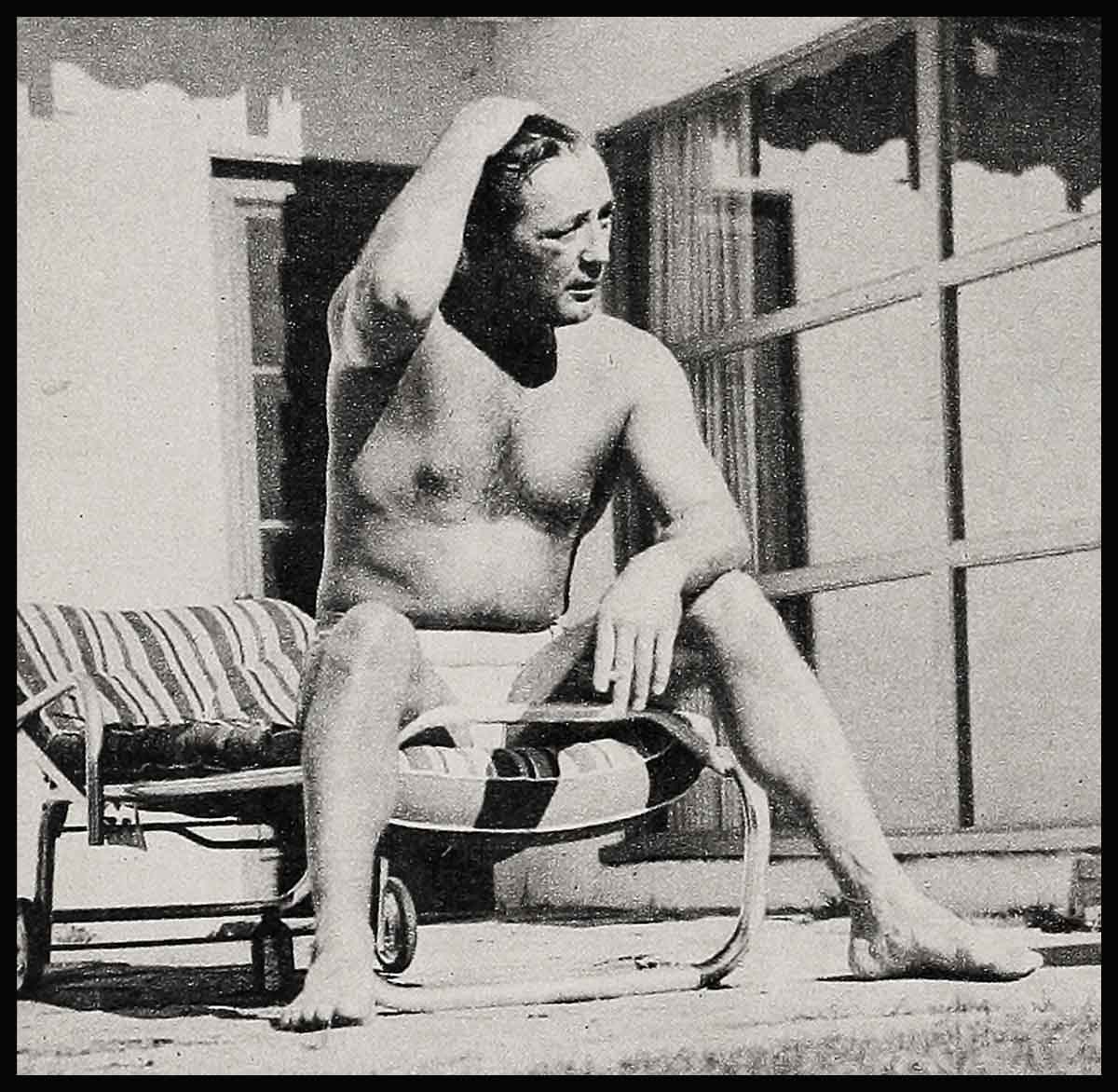

Or like Stanley Kramer, who was deafened but undaunted by the wails of anguish from the reading public when he east Mitch in the role of Lucas Marsh in Not As A Stranger. Wrote Kramer, less in self-defense than pride, “We knew the instant we laid down the script after the first reading that Mitchum was Lucas Marsh. We consider Bob’s crinkly-eyed loping through a decade of bad pictures not the faintest indication of his talent as an actor . . . there is no reason why a dedicated idealist has to look or talk like an underfed Shelley. Mitchum has the power, the sex, the violence and—above all—the brains to be Lucas Marsh.”

It goes without saying that Robert Mitchum had not sought the controversial role, though he might well have been the only star in Hollywood who didn’t covet it. When he was approached, never having read the book, he said, “I’ll read the script, and if I think I can do anything for the picture, okay. But I’ll tell you this: after I’ve read it, if I think Monty Clift or Brando would be better for you, I’m ready to say so.

This being the acting plum of the year, one of the men sitting in on the conference was understandably confused. “What gives with this guy?” he appealed to Stanley Kramer. “It sounds to me like he doesn’t want to make the picture.”

“No,” answered the smiling Kramer. “He’s just being honest and you can’t ask for more than that.”

As it happened, things didn’t work out that way; Robert never laid eyes on the script before the deal was closed. He was on location while the final shooting script was being prepared, and when he got back he found Kramer in a bind for time. He needed an immediate yea or nay, because two other top stars were holding themselves in readiness to slip into the role if Mitch should turn it down.

The momentous decision took about this long: Mitchum asked, “Do you think I’m right for it?”

“Yes, Bob, I do,” said Kramer.

That was all. Without even knowing what the role would demand of him, Mitch said, “I’ll do it.” A pretty big decision to leave to someone else, but he was serene and untroubled in mind. “I knew I could trust Stanley’s judgment,” he commented later. “Who knows more about making pictures?”

The critics who like to characterize Mitchum as an irresponsible slob who merely happens to affect women the way uranium affects a Geiger counter would have had a tough time recognizing him during this production. Working for a man he respects on a picture he believed in, Bob was a model of decorum. Granted that he, Frank Sinatra and Broderick Crawford present an explosive array of potential mischief, Robert was too busy riding herd on his supercharged pals to get into any trouble on his own.

There was the sentimental moment when they decided that buddies should not be separated ever, by anything, whereupon Brod calmly kicked the door off the dressing room in which they sat. The other doors soon followed—but Mitch was there to exercise restraint before the walls came tumbling down.

And there is the story that Frank himself has told all over town. “I went to a party one night, and the next morning I woke up in my dressing room at the studio. An icebag was on my head, pads were on my eyes—all the work of Mother Mitchum, who was hovering anxiously over me. After he got me some coffee, he went over to the set and stalled through a couple of scenes until old Snodgrass was ready to work.” To this day The Voice is known as Snodgrass to the big guy, who goes under the unlikely name of Mother.

As insurance against the loss of his good intentions, it seemed advisable that someone should also ride herd on Mitch, a chore courageously undertaken by Olivia de Havilland.

“You read in the columns about the time she slapped a can of beer out of my hand?” Bob shook his head, obviously tickled. “I never did find out what she’s got against beer.

“We were shooting out at the airport for a couple of days, and during the breaks all the guys would go to this joint to have a beer. Except me. Olivia would grab me by the arm and say, ‘Now you stay here! I won’t have you wasting yourself, swilling that filthy stuff!’

“One day I was having a beer with my lunch when she walked in. She looked to see what was in the paper cup, flirted around with it, and then—flick—over it went!

“I asked her, ‘Are you satisfied now?’ She said yes, so I said fine and got myself another beer. They reported it as an incident in the columns, missing the whole point: Olivia was laughing so hard she could barely talk the whole time.”

That was what was missing from the then-current Robert Mitchum story—the incidents. He had been working hard, making in quick succession, Track Of The Cat, Night Of The Hunter and Not As A Stranger without incidentally making any headlines for misconduct. Not even a traffic ticket for burning up the roads in his hot little Jaguar. Mitch was beginning to look like the peace-loving guy his friends have always claimed him to be.

One such, Jane Russell, said, “All people see is Robert making a shambles out of some place because somebody gave him an accidental nudge. What they don’t know or care enough to think about is that he has already been shoved across the room without opening his mouth before that last little nudge causes him to blow up.”

People do anticipate the blow-ups, though, and they were not disappointed when John Wayne flew up to the San Francisco Bay area to replace Mitchum as the star of Blood Alley. The reasons given were numerous. It was said that Mitch carried his rough-housing too far when he dunked a crew member in the icy drink—which would be an incredibly childish thing to do. It was said that he created disharmony within the company—but those who work with Bob swear by him as well as at him. True, in Canada he once belted an inquisitive bear over the snout with a short-handled spade, but technically the bear was part of the scenery rather than the company. And it was said that Director William Wellman found him fractious and unmanageable, which has an odd ring. Mr. Wellman isn’t called Wild Bill for nothing.

“A great story,” commented Mitch laconically, “except that none of it ever happened.” True to form, he was completely disinterested in telling his side of the rhubarb. But Mitch never fights it; he couldn’t care less for the sound of his own voice saying, “I wuz robbed!”

Apropos of Blood Alley, what actually happened could be the story of Mitchum’s life: he told the truth to a man who laughed when he should have been listening. Mitch’s is not a simple personality, to say the least, and he is shatteringly direct in his efforts to remain as uncomplicated as possible. On this occasion, a party, he was approached by a gentleman who wanted to make a film deal, and this was not the kind of man with whom Robert deals. If he had been evasive, suggesting that they discuss it over lunch at some nebulous time, the man would inevitably have called to set the date. So, in forthright Mitchumese he said instead, “Look, I’m not interested in a picture deal with you. I don’t like you. I heard about you before I met you, and you’re even worse than anything I heard.” This is not to imply that it is the right way and it certainly isn’t the tactful way, but telling the unvarnished truth is Mitch’s way.

The film executive thought he was kidding, as people all too often do. With a nervous giggle he said, “Bob, you are a character!” and moved on to greet some other people. A few minutes later he was back, making the same pitch about a deal, and Robert, who thought he had made himself clear the first time, became irritated. He coupled a few words unsuited to these pages with the opinion that the gentleman was no less than the village idiot and stalked away.

What happened next? “What happened,” was the dry contribution of Bob’s alter ago, Reva Fredericks, “is that Robert’s ‘village idiot’ figures rather prominently in the future of Batjac Productions. He went home and thought about it for a few days, and the next thing we knew, Robert was out of Blood Alley.”

“Well, Duke Wayne and Bob Fellows couldn’t afford to keep me in the cast once he started turning the screws,” Mitch said reasonably. “After all, their pictures have to be released by someone, so these guys can’t go around antagonizing important people for the sake of a principle. They couldn’t let me make the picture, and if they had fired me without cause, I’d have sued for a million bucks. Robert Mitchum had to be made to look like a naughty boy.” There was the familiar, artistic shrug. “Duke and Bob? Sure they’re still friends of mine—why fight City Hall?” Now that it was over and done, there was no animosity in him. Only a mild, amused contempt for the man who would take out his malice in such a petty, underhand way.

They were at lunch, Mitch, Reva and a friend. Reva Fredericks is Robert’s secretary, a lively, cool-eyed girl endowed with more than her share of brains, who would just as leave be shot as to see her name in a story about the boss. She is also his friend, advisor and chief brow-beater, and at the time she was giving a working demonstration of what happens when you tell people the truth and they don’t believe you. And Mitch was enjoying her frustration to the utmost.

Reva’s problem was a waiter of the sort who relies on his talent as a comedian to cover up for extraordinarily poor service. The entire time she attempted to order, he was offering feeble jokes to Robert, so that she had to repeat herself several times. She told him to bring Mitch a large salad and some Melba toast; he brought a side order of salad and no toast and asked what Mr. Mitchum would like to have for lunch. He forgot to bring the basket of hot rolls, it escaped him that coffee had been ordered with the meal. When he did get around to bringing it twenty minutes later, it was stone cold.

“You,” Reva addressed him, “are an inefficient moron.” That fractured him.

Next time around, she tried again. “I’ve got news for you, you bumbling idiot. I’m going to sign the check for this meal, and if you think you’re going to get a nickel tip, you’re crazy.”

That made her almost as funny as he was, and he laughed fit to bust.

The service didn’t improve, though, and finally Reva said, “Look, go away. Tell the maitre de I want to see him—and don’t come back.”

“Sure, sure, Miss Fredericks, you bet, first thing,” he chortled, trying to chuck her under the chin.

She shook her head in desperation. “He thinks I’m kidding. I tell him exactly how it is and he thinks it’s a big joke.”

The entire time she belabored the waiter, Mitch grinned from ear to ear. “Did she learn this from you, Bob?” he was asked.

“No,” he said, “but it’s her defense against me. Any time I start acting up, she clobbers me, too.”

“Before the smoke had cleared away on the Blood Alley situation, Robert had fired me fourteen times and I had quit fifteen times.” Which nonsense probably ceased only because they ran out of harsh truths to hurl at each other.

Mitchum yawned and stretched hugely. “Man, I’m tired! You know how I spend my life? Reading scripts. I’ve got one more picture commitment, a western for Sam Goldwyn, Jr., and that will be a hundred and seven I’ve made. When that’s done, I’m gonna blow. Dorothy and I are going to get on a slow freighter for Spain, Portugal—around there. Spend four months, maybe. Sheldon Reynolds talked to me about making a picture there that would only take ten weeks. I may do that.

“But mostly, I just want to loaf. I’ve got a friend, a writer named Jim Phillips, who lives down in the Canary Islands.” The sleepy eyes glinted with mischief. “Now, there is a bright boy. He liked it so much down there that he wanted to stay, but he couldn’t find a place to live. All the houses are on the banana plantations, and of course the owners live in them. Jim looked the situation over and found that the house he liked best of all belonged to a beautiful, twenty-two-year-old contessa. Since he couldn’t rent the place, he married the girl.

“That’s for me. I’m gonna go down there and visit old Jim and just lie there under a banana tree.”

He rose to his not inconsiderable height, suddenly turning serious. “Now I’ve got to go. I’m going over to Beverly Hills to buy Dorothy a present.”

“You think you’ll make it this time?” Reva asked sympathetically.

“I’m going to try,” he answered, looking grim. Then his awful secret came out: Mitch has demophobia. The guy who can call a studio head the village idiot without turning a hair is petrified by the perfectly ordinary people on the streets and in the shops. Not because they stare at him, though he doesn’t like that any more than any one else. Not because he’s so easily recognizable that shopkeepers pull out their higher price tags immediately—that’s human nature, and Robert would be the last one to quarrel with nature.

“I don’t know what it is; I can’t define it,” he said slowly, “but I’ve been that way all my life. I get the feeling that I can’t breathe. Sometimes when I have something to buy, I drive around in circles, trying to make myself park—and then I light out for the hills.”

“I’ll buy it for you, Robert,’ Reva offered.

“Nope,” Mitch answered as he jackknifed his long legs into the Jaguar. “I’ve got to get over this some time, and today may be the day.”

He didn’t say goodbye or even wave when he roared off. But then, he never does.

THE END

—BY TONI NOEL

It is a quote. MODERN SCREEN MAGAZINE JUNE 1955

No Comments