Between Heaven and. . .

PART I

Late one afternoon, several years ago, Anne Baxter climbed miserably into bed in a Montreal hotel. Her skin was covered with ugly red hives. She was shivering. Already the star of some twenty-five Hollywood movies, Anne was now touring the North American continent in a stage presentation of “John Brown’s Body.” She was scheduled for a performance the very next evening; it was no time to be ill. She telephoned the company manager, who sent for a doctor.

When the doctor arrived, he took a seat beside Anne, while she attempted to tell him what was wrong. She began talking and seemed not able to stop. He didn’t try to interrupt. It was clear he sensed that the hives were symptomatic of a serious State of emotional unrest and that a little truth-telling might well be therapeutic. But as the doctor listened, he realized that he was getting not only an insight into the private life of an actress, but also hearing truths about Hollywood and its way of life which are seldom if ever brought to public attention.

AUDIO BOOK

“How can I go on before an audience tomorrow night?” she appealed. “I have to look beautiful and poised and be sure of myself. I feel so far from it!”

She went on from this to dip into her troubles as an actress generally. But after a while she was no longer talking about her professional problems. She was talking about the personal problems of Anne Baxter, woman.

By this time she was crying. As if she too realized that the only way to be rid of some inner affliction was to purge herself, she was pouring forth a long tirade of self-condemnation. She said that she had grown up only in certain ways, ways that were necessary to fulfilling her ambitions. In other ways she had never grown up. She spoke about her marriage and blamed herself for the divorce which ended it.

“Our greatest fault, my husband’s and mine,” she said, “was that we couldn’t fight, and let the truth out. We were too reserved. Or too frightened, if the truth be known, to let our real differences emerge. We avoided, as too many couples do, those honesties through which you come to grips with a marriage and handle it. Or handle yourselves.

“I blame myself most because I was the woman. It was my business to see what was happening. And if I had really been in charge of myself, instead of master only of that part which was ambitious and self-seeking, there might never have been a divorce. And even then, there might have been a reconciliation. It sickens me that what I have left behind in my life aren’t footsteps in the sands of time, but footprints in cement. It can be too late!”

The doctor busied himself to give her a sedative. After a while it began to take effect, and her eyes grew heavy-lidded. He rose quietly to his feet, but before he could go, Anne had a few more words to say, this time (and the doctor had to smile inwardly) spoken as an actress, as if she well knew what was happening and was trying for a good curtain line . . . and the lines came out all mixed up.

“I so often think of the play ‘Our Town,’ when Emily Web, the young girl who has died, comes back from her grave for a brief interlude. She tries to establish communication with her family and fails. Finally, sadly, she has to say, ‘Oh, it all goes so fast. We don’t have time to look at one another. I didn’t realize—all that was going on and we never noticed.’ ”

Now the actress fell asleep. The doctor lowered the shades and tiptoed from the room. When he reached the lobby of the hotel, he telephoned the company manager and told him that he saw no need to cancel the show the next night. Miss Baxter would be able to go on.

The doctor was right. Anne Baxter went on and performed well. She has always been able to go on. It is only in real life that she has failed to perform in a manner calculated to bring a full measure of happiness. This is purely because she hasn’t done a good job of playing the most important role of all—the role of Anne Baxter. She is both too intelligent and too honest to think that she ever will.

“I know now,” she once said, “that the life in Hollywood which I had to lead, that any inordinately ambitious young actress has to lead, is like walking through a mine field. What you stand to lose, with each mine you touch off, is another phase of your own identity—your all-important, personally possessed you. It means a steadily increasing inability to be yourself during those precious moments when it is only as yourself that you can be touched by the heart’s warmth we all hunger for. Real friendships. Even more fleetingly, real love.

“After a while you know the field is mined, and you know what is happening to you. But you can’t help it. You still walk through the field. And when you get blown up—and you do—you try in a dazed way to put yourself together again. The only trouble is that you can’t put yourself together exactly the same as you were before. There is a difference. And you don’t always like this difference. It sometimes even frightens you, and you try to hide your fright from the members of your family or your close friends. ‘Is this what I have become?’ you ask yourself.”

What has happened to Anne Baxter is not uncommon. It is true, probably, of most sensitive feminine stars, and of practically all the more beautiful and successful ones. But where an Ava Gardner or a Marilyn Monroe or a Rita Hayworth will seek sooner or later to leave Hollywood, as if by so doing she will thus be able to leave her unhappiness behind, an Anne Baxter is under no such illusion.

“That’s just kidding yourself,” she commented recently. “Between an actress’s private life and her professional life there can be no partition, as so many have so hopefully claimed. After you’ve made your bed, you can’t lie on it a woman in love one minute and a public personality the next. Each conflicts with the other and both conflict with the inner you. The ambitions, the crackling nerves you take to the studio you take wherever else you go. They are damningly still with you when you want to take your hands off the controls and be just a woman.

“You can get pretty desperate because this is true. Because whatever the magic of stardom is, with all its lights and glamour and shouting, it is not the magic that leads to simple fulfillment. In time this has its effect on you. I have become, quite frankly, a manic-depressive, saved only by—thank God for it—a sense of humor. When I feel good I feel so wonderfully good. But Lord, how low I can get, and how often I go through the cycle!”

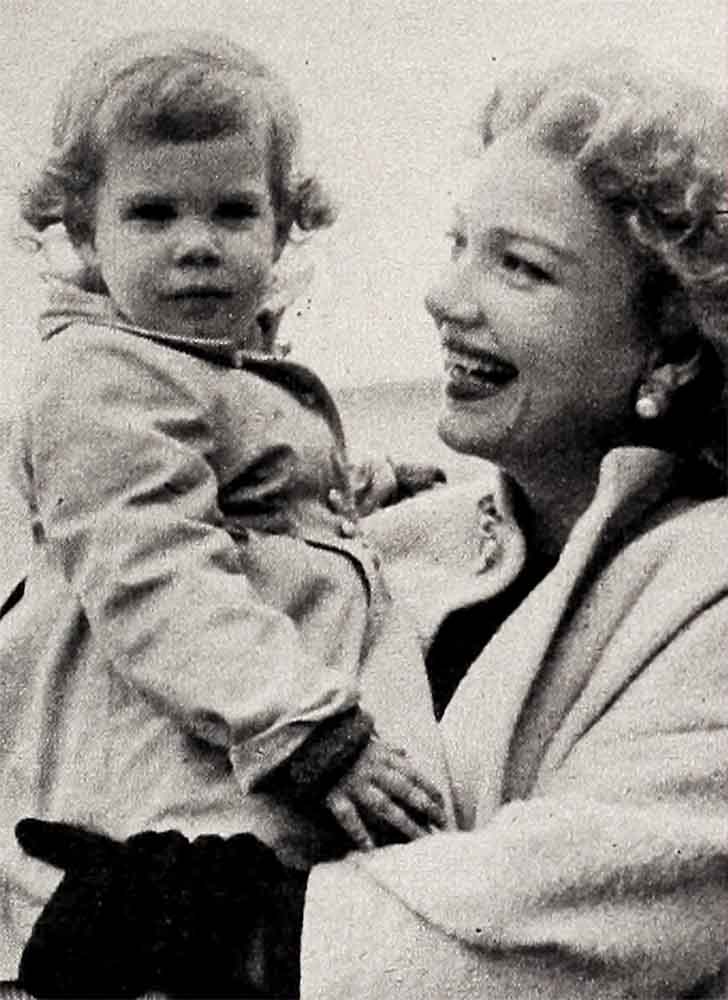

A hazel-eyed, intense girl who has always had to fight off a tendency to be pudgy, Anne is successfully slim as she now enters her thirties. She has lived quietly with her five-year-old daughter Katrina, ever since her divorce in 1953 from John Hodiak, who died of a heart attack a little more than a year ago. Anne’s home is now a shrubbery-hidden, smartly remodeled Hollywood house located just above the Sunset Strip, where are gathered all the town’s night clubs—to which she rarely goes.

She has a fervor for acting that is as strong today, apparently, as it was when she was just a child living in Westchester County, New York, and begging her folks to bring her to Manhattan to see the Broadway plays. She can remember every part she has ever had, from her grade-school roles to her latest ones in Cecil B. De Mille’s “The Ten Commandments” and in “Three Violent People.” This was aptly demonstrated one evening about five years ago when she happened to be eating with Hodiak in a Beverly Hills restaurant. The waiter brought a note from a diner who had observed her enter.

“I was your leading man once, in the sixth grade at Horace Greeley School in Chappaqua, New York,” the note read. Anne took one look at the signature and wrote a quick reply. “No, I was your leading lady,” she corrected. She was right. He had been the star.

She is very precise about such things; she tends to date events by the roles she happened to be playing when they occurred. “It was just before I worked in ‘Sunday Dinner for a Soldier’ that I met John,” she will say. This was in 1944, and John, incidentally, was also starred in the same picture. While making the film they fell in love. “But,” as she has also said, “it wasn’t until I was cast in ‘The Razor’s Edge’ that I decided to marry John.” That was in July of 1946. Their little daughter was born in July of 1951, or, as Anne would put it, just before she worked in “The Outcasts of Poker Fiat.”

A deep unhappiness made itself evident in their lives a year later and they were unable to cope with it. She won her divorce decree from Hodiak at a time when her name was being linked romantically with director-publicist Russell Birdwell.

If Anne Baxter’s cup is not brim full today, it is all the more strange because she never needed Hollywood in the first place. But it seems that little girls who are also stragestruck are made not only of sugar and spice but great gobs of dissatisfaction as well.

Anne’s parents, Mr. and Mrs. Kenneth Stuart Baxter, learned this about their only child when she was barely able to talk. Mr. Baxter, vice president of a distillery Corporation, was quite well-to-do. Mrs. Baxter’s father was, and still is, a world-renowned figure in architecture, the much discussed non-conformist Frank Lloyd Wright. Anne had only to accept her status to gain for herself a good life, it would seem. But this was too easy. This she would not do.

“Some people have to overcome the handicap of adversity to get places,” she once explained. “My barrier, I knew right from the start, was the cushion my birth had put behind me. all I had to do was lean back and live comfortably. I was frightened at the prospect, because I knew it would take the fight out of me, make the life I craved seem less important. It is hard to remember exactly how you felt as a child, but the essence of it all was, I think, that I wasn’t satisfied being just myself. Nor did I want to be some beautiful, mystical creature. I felt a great urge to be useful . . . through acting. Besides, if it isn’t enough being just you, what better place than the stage to be someone else?”

Anne was not yet twelve when she was studying the theatre in a dramatic school in New York. This was after her folks had moved to Chappaqua from Michigan City, Indiana, where she was born. She was not yet fifteen, had been an acting apprentice at the Cape Playhouse and had done three Broadway plays when she was invited to make a movie test by the then titan of picture-making, David O. Selznick. Her mother chaperoned her West, and Anne has never forgotten the afternoon she was ushered into Selznick’s office in Culver City.

“I thought this was the moment when my dreams would all take real form,” she reports. “Somehow I had found out that they wanted me for ‘Rebecca,’ to co-star with Laurence Olivier, under the direction of Alfred Hitchcock. My head was filled with this upper realm of acting which I was about to enter, and I planned to conquer Mr. Selznick with my poise and beauty.

“ ‘How do you do?’ I began, as soon as I was in his presence. I waited for him to jump up and greet me.

“ ‘Come here,’ he said. ‘I want to look at your teeth.’ ”

Mr. Selznick got to look at Anne’s teeth, and she did not, as was her wild impulse at the time, neigh like a horse while he was peering at them. In any event, the tests (she made eight of them) did not win her the part she was up for. The makeup man did his best, but Anne kept looking more like Olivier’s daughter than his bride. The role went to Joan Fontaine. But Anne had made an impression, and within a few months she was offered a term contract for $350 a week at 20th Century-Fox Studios. She was still only fifteen.

Her father’s business was in the East. Her mother wanted to stay with her husband. But a great new world was calling Anne, and they had only to look at their daughter to know that she would explode on their hands if they did not give in to her. Mrs. Baxter came to California again to establish a home for Anne. Mr. Baxter set about trying to transfer his business interests to the West Coast as well. It was to take several years before he succeeded. In that time Anne had worked with Wallace Beery in “Twenty Mule Team,” with John Barrymore in “The Great Profile,” with Dana Andrews in “Swamp Water” and with Orson Welles in “The Magnificent Ambersons.”

Wallace Beery was aghast at her eager-beaverness, and urged her to slow down. John Barrymore watched her trying to give her part everything she had, gestures and all, and asked sarcastically, “Does she have to swim?”’

She was properly impressed by her first co-starring role, but in her following picture Orson Welles had only to glower at her once to calm her down.

Anne at seventeen looked it, or perhaps less. She hadn’t the mature appearance that some girls achieve early. She was truly unsophisticated. once, in a scene in “The Great Profile,” Barrymore let loose a long string of invective in her presence, but she wasn’t aware that he was cursing until director Walter Lang made him apologize to her. Anne had never before so much as heard any of the words Barrymore had used; she certainly didn’t understand them.

As a matter of fact she spent a great deal of her time then trying not to be shocked—or at least not to look shocked—at the things she was hearing and seeing in Hollywood. With a sort of schoolgirl instinct she tried to conform. When people she was with laughed at something, she laughed too, though she generally had no idea what had been said that was funny.

She used a little mascara, a little lip— stick and felt she was a dud in conversations because she had no “line.” She had been a good student and could talk well on general subjects. But Hollywood conversations had a gambit all their own, which ran to gossip about persons, studio opportunities, romantic opportunities, any old opportunities, beds, houses, love and cars—in about that order. On such subjects she found herself nettled because she wasn’t in the know, afraid of being considered gauche. She came home from parties dissatisfied, impatient with having not yet lived, and vaguely convinced that she owed it to herself to do something about it. And about this time she had her first “adventure.”

It had its beginning when her mother was called away and asked a friend of theirs to act as a companion and chaperon for Anne. After her mother left, Anne decided that she didn’t like this arrangement. She told the chaperon that she was going to spend the weekend with a girl friend in Catalina, and promised to return Monday morning. She actually did go to Catalina on Saturday, but she came back to Hollywood on Sunday instead of Monday. instead of going home she got into her car, which she had left at the boat dock, and drove off. That evening the car was parked alongside the lake in Sherwood Forest, and Anne spent the night in the car seat. It was an escapade in every sense of the word but one—she was alone.

Choked with restlessness, feeling strange compulsions, she sat frozen through most of the early hours, sometimes weeping, and shaken by the fancy that she was rehearsing to be a bad girl.

That night, Anne came to comprehend something about herself that she now knows to be true and is trying to correct: Her thinking had mostly just an emotional basis. And she knew, too, that this would be a heavy burden for her. “Like carrying yourself on your own back,” she thought. But there was nothing she could do about it then.

“The world to me was like a boy I was crazy about and going out with,” is the way she has described her feeling of this period. “The boy carries himself well, he is smart, he smokes and drinks and knows all the latest references, and I haven’t any convictions of my own but just try desperately to keep up with him. I’m not comfortable as myself, so I try to be somebody else. Somebody who laughs, has a gay time, acts as if she knows just what is going on, and how she is going to fit into life. But she doesn’t. She doesn’t really!”

The car in which Anne spent that night was a Cadillac that she had bought from a Turkish gambler in Hollywood. It was a black coupe, and she called it both “Ferdinand” and “Ticket to Freedom.” It had not only a horn, but also a set of bells, which she’d added. Anne drove to Sherwood Forest Lake because on a previous visit she had fallen in love with the wild ducks there. On her way home the next morning, teeth chattering, she kept telling herself, “You have to do something. You have to be what you are even if you freeze to death!”

She remembered that once, when she was thirteen, she had made a movie test in New York and thought it was terrible. She had sunk lower and lower into her seat as it ran on, and the director who had had charge of it tried vainly to console her.

“We can compare anything in the world except the thing about ourselves that makes us unique,” he had explained. “That we cannot compare with anything. You’re having a peek at yourself as others see you . . . and that is always a shock!”

But this hadn’t helped. She had squirmed way down into her seat, couldn’t take her eyes off herself on the screen, and hated what she saw. “I knew then that I was going to have a lot of trouble with myself,” she said.

Before the next year was over, after her Sherwood Forest episode, Anne, hardly eighteen, rebelled against her mother’s authority. She wanted to live alone. Among girls of her age this was a fairly unusual thing at the time, but it was certainly a questionable move to make in Hollywood, where the abysses were many, and of extra depth. Yet it came to this: Tired of fighting with Anne, her mother left. But not without misgivings.

Anne was not on her own the very moment her mother left. As a matter of fact, Mrs. Baxter first exacted a promise that Anne would stay with friends, the late Nigel Bruce and his wife, Bunnie, while a maid could be taught to keep a home for her. Anne lived with the Bruces for four months, during which time a girl was hired and trained. But when Anne rented an apartment in Westwood and moved in, thrilled at having her own menage at last, the new maid began developing “stomach attacks” which eventually were revealed to be alcoholic binges.

The maid did not wait to be dismissed. She left of her own accord. But Anne did not go back to the Bruces. In her ears rang warnings from her mother. But Anne was in her own place at last, and she intended not to lose the independence she had finally gained.

Not many of Hollywood’s actresses have an actual love for the fine lines written for them in their pictures; for the most part they are not talented in the arts at all, outside of the art of giving of themselves to the characters they play. Anne Baxter is different, in the sense that she has a fine taste for words—often to the point of poetry. Speaking of a fine Paris rain, she once said, “It sprinkles you like a nice fat laundress doing her ironing.” “Venice,” she wrote home in a letter, “is so beautiful it can grow you a new heart if you have lost your own.” She has talked of Mexico’s little burros, “tiptoeing through the village.”

At eighteen Anne was talking a lot about boys. Most of the boys she met were between college and settling-down age, when World War II further upset their plans. She recalls, “No one knew anything, except that it was a good time to have fun. If you were a girl and didn’t want to mope at home alone, you went along.

“There were goodbye parties for boys going to camp, last-leave parties, hello parties and first-leave parties. The boys seemed to feel that they had nothing left in the world but what they could grab. They grabbed for drinks, for laughs, for you. It was a time to get what you wanted because there might not be any other time. And for youth, time has always seemed like that anyway.

“I remember I learned how to drink then, even though I didn’t like to drink, and still don’t. They were all fancy drinks, concoctions with your initials outlined on top of the liquor in nutmeg or the like. It was very smart to drink them. It was very smart to stay out all night, or mostly all night. It was very smart to brag of having come home at four in the morning to sleep an hour, then take a shower and rush off to the studio.

“It was terribly smart, terribly gay, except when it would become suddenly and terribly shocking. A boy you thought you loved and with whom you had stolen some moments of tenderness and magic would walk off into a matter-of-fact dawn with a casual, ‘Well, so long,’ leaving you standing mortified, maybe laughing ruefully at yourself, in a ringing emptiness that you knew to be closer to your real life than all the wild pretending you had been doing.”

It was about then that Anne Baxter began wondering whether this was really what she had wanted. Whether freedom that could turn out to be abandon was really freedom. Whether this running around too much and laughing too much and crying out “fabulous” at stories she didn’t even understand, was really what she wanted. And the answer that came to her was short. “No,” she told herself, “that isn’t it, either.”

She told herself more than this. Anne knew she was afraid of something. She was afraid that she was developing many false faces in Hollywood, without ever having found her own.

“Suppose a man fell in love with one of these false faces?” she asked herself. “I’d be playing a dirty trick on him—and on myself.”

She decided that she wanted very much to wear her own face, to be herself. And she knew it for a certainty one morning, in the home of Alfred Hitchcock, when a dark-haired man with a strongly masculine cast to his features walked into the room from the garden. She had never met him, but she knew his name. His looks were like a challenge to her, and she accepted the challenge. He was John Hodiak. He didn’t give her as much as a smile that first morning.

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE APRIL 1957

AUDIO BOOK