Audrey’s Harvest Of The Heart

The search for happiness, like the search for truth, is a lonely one. No one can tell us when we’ve found it, and few of our friends agree with us when we raise our voices to shout exultantly, “This is it!”

Audrey Hepburn is no exception. Following her searching heart, consulting that heart and not her head, as all true lovers do, Audrey found her happiness in a most unlikely place—or so said her friends, and her critics, warning her against Mel Ferrer. Not that they had anything against him—they didn’t. As a man, as an actor, as a person, they tossed Mel their accolades and their approval. It was only for Audrey. “He’s too old for her,” they said, though the difference in their ages is not really great. “He has too much influence over her,” they sounded their ominous warning. “He’ll resent it when her career outstrips his,” the gloom-sayers and the doom-sayers predicted, carrying this one step farther. And, all the time, they were trying to analyze what cannot and could not be analyzed—which is, simply, the fundamental appeal that attracts one human being to another, regardless of the seemingly insurmountable barriers which must be overcome before love can find fulfillment.

Audrey once said of herself that her greatest asset is her discontent.

It was a professional reference, of course, meaning that she always refused to be wholly satisfied with her work. But, hearing of this, a friend and admirer commented: “Discontent is also her greatest personal liability.”

This comment was made several years ago, before Mel Ferrer had appeared on the scene, and it was not entirely untrue—then. Discontent was not the precise word, but it was a distant cousin. It is truer to say that, when Audrey Hepburn left Paramount after making “Sabrina,” she had not yet found herself, found the woman she was to become. Her life was singularly intense and one-dimensional. She loved her work, as she loves it now, and that ruled out discontent and its various implications. But she didn’t have much aside from her work; she was living for Audrey Hepburn’s career. Today, she still takes that career with utmost seriousness. But it constitutes only one dimension in her life. The perspective has shifted and widened since she fell in love and married. In the process, Audrey became a woman. The change may be indescribable, but that hasn’t stopped her friends from trying to describe it.

“I’ll tell you,” said one of them recently. “Two years ago, she was a pixie. You didn’t know but what she’d suddenly climb a tree or hurdle a hedge or just vanish in a spiral of smoke. Now you’re reasonably sure she’ll eat a ham sandwich and go to a ball game—or whatever.”

Said another: “We’ve always loved her here on this lot. But, before she met Mel, you sensed something—maybe it was unhappiness or insecurity, I’m not really sure. But there was a sort of fragility of temperament; you handled her with care. Now—well, what I’m trying to say is, now I know her. She’s an entirely different person since her marriage to Mel.”

“I hate to labor a word like this,” said a third friend. “But this girl is transfixed. Happiness in love has turned her inside out.”

Now let’s hear what Audrey herself has to say on the subject.

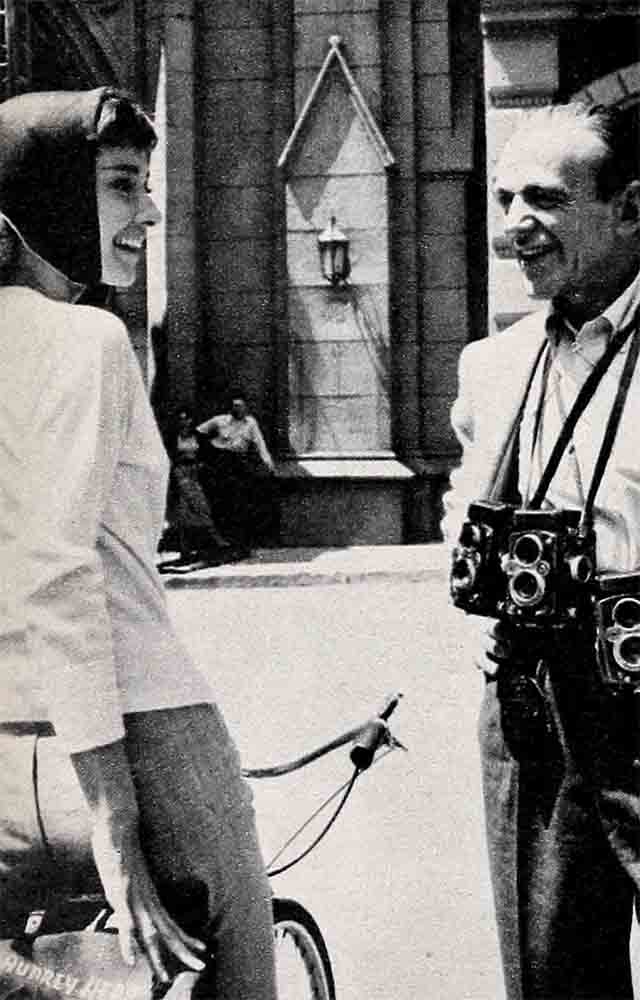

Having completed “War and Peace” in Italy, Audrey was back in Hollywood, but only long enough to make some scenes for “Funny Face,” with Fred Astaire. Then she would be on her way to France to finish the film.

Audrey sat in her period dressing room, wearing slacks and eating fruit salad and sliced cold meat. No endive. Never in her life will she again eat endive. As a child during World War II, she once survived for days on nothing but endive. Just the thought of it now turns her stomach.

When asked about the change in her, Audrey grew thoughtful and said, “I want to be agreeable, but I want to be accurate, too. Perhaps the words used are too neat. I mean, if I was discontented, I wasn’t aware of it then. I was very busy. But looking back, perhaps it was so. I never had any conscious feeling of insecurity, but I suppose many insecure people are that way. I—I don’t think now that I was a whole woman then. No woman is, without love. I was dedicated. My work, my dance lessons, terrific application—I thought this was enough. Now I know it wasn’t. Mel has meant—well, everything.”

Here there seemed to lay the seeds of conflict. In other words, if Mel so wished it, would Audrey forsake her career?

She considered the question for some time. “If you’ll forgive me,” she said finally, “it’s not a fair question. It sets up an issue I don’t think would ever arise.

“If Mel,” she said, “put it to me that it was of the most vital concern to him that I retire—yes, I would. But it would make me very unhappy. As I say, though, I can’t imagine his doing it. Oh, perhaps if— if something drastic happened, something I can’t even conceive of, at the moment. But Mel knows what my work means to me. He likes for me to work if it makes me happy. We work together. Some author once said, a writer’s only salvation is to write. It’s that way with us, too, perhaps. The question upsets me a little, because I think I know where it comes from. All this talk, especially in New York, that Mel is a kind of Svengali to my Trilby, dominating my career. It’s so ridiculous and so unfair to Mel. He advises me, yes, and sometimes I advise him. Isn’t it that way with all couples? We want to help each other, it’s one of the wonderful things of marriage. But dominating—oh, no!”

Audrey and Mel were married in Switzerland, in September, 1954, not long after the Broadway run of “Ondine,” in which he was her co-star. The news raised the eyebrows of many right up to the hairline, and a few were muttering “Svengali” before the honeymoon even started. But they were wrong. “They” are wrong so often, it might be wondered sometimes why “they” even bother to come to bat. The Ferrers honeymooned in Europe and were ecstatically happy. They lived on an Italian farm for a while and, while Audrey made “Funny Face,” they rented a beach house at Malibu, which they both loved.

Since they have yet to own a home of their own, they are tireless house renters.

“We’d love to own one,” says Audrey. “But not yet. We go wherever our careers take us, where the good roles are to be found. It would be silly to buy a home and then spend a year or more away from it. But we have a villa in mind like the one we had in Italy, and one day we’re going to have it—perhaps perched on a California hillside near the ocean.”

But, as she says, not yet. First there are pictures to be made, in Paris, maybe Rome, maybe London. So for the present, Hollywood is just another way station, and the villa by the sea a somewhat remote dream.

“Anyway,” Audrey continued, “sometimes things get printed and there’s nothing you can do about it. After all, you don’t complain when the words are praise, so it should work both ways. But now and then—oh, I don’t know. For instance, today I’m having lunch in my dressing room. Well, I usually do—have lunch in my dressing room, I mean. Being alone, I re-charge my batteries. Anyway, I thought I was being a good girl, giving my all to the picture this way. But then one of the columnists—and one I thought I got along with—wrote a line about what goes with snooty Audrey Hepburn, not eating in the commissary. I never thought of it that way. So now do I have to begin eating in the commissary just to pacify this columnist? I’m afraid it would be cowardly of me. He’s committed me to a course of action.”

Returning to the subject of love, Audrey’s eyes grew tender as she said, “For me, the growth has been in the giving and the strength in the sense of protection. I’m not alone any more. Don’t make that sound pathetic. I never minded being alone. But I’d mind it now. I didn’t know it then; I do now: no one should be alone. But when I was last here, in Hollywood, my every movement was for Audrey Hepburn, and in a way that makes you ingrown. Now I know what it is to—how else can I say it?—live for another. It has an archaic sound, but that’s how it is. I’ve been restless, but that’s over. I didn’t know exactly where or what I wanted to be. Now I do. Wherever Mel is, I’m home.”

And, in truth, home has been an elusive project for Audrey. Her life reads a little like an improbable operetta—but a dead serious one. She was born in Brussels, Belgium, in 1929. Her father, J. A. Hepburn-Ruston, was Anglo-Irish. Her mother is of Dutch nobility.

Audrey was tomboyish as a child, loved animals and had no regard for dolls. (“They never seemed real to me.”) In 1939, her parents were divorced, and when the war came Audrey went to stay at Arnhem in Holland. It was there, one day in 1940, that she fell in love with ballet, after seeing a performance of the famed Sadler’s Wells. She went home that night determined to be a ballerina. The next day the Nazis invaded.

Arnhem in those years was a grim and fantastic place for a child to be. Audrey learned ballet and sometimes carried underground messages in her shoes. Her attitude toward the Nazis was, of course, far from amiable; her English was completely fluent. She was hungry much of the time. But she came out of it all in one piece.

For three years after the war, she studied in Amsterdam, then in London under ballet director Marie Rambert, who once said of her: “She was a wonderful learner. If she had wanted to persevere in ballet, she might have become an outstanding ballerina.” Lack of perseverence is not ordinarily one of Audrey’s weaknesses, but then she had a feeling that time was running out. She was in a hurry. The search had begun in earnest.

She got chorus girl and night-club jobs, such as in the London company of “High Button Shoes.” But all the time she studied, too. Then fate, that literary convenience, took her to Monte Carlo for a bit part in a picture, and there she was spotted by Colette, the famed and respected French authoress. Anita Loos, the playwright, had just then completed a dramatization of Colette’s book, Gigi. Colette took just one look at Audrey Hepburn and said: “Voila!” Miss Loos agreed.

When it opened on Broadway, “Gigi” turned out to be less than a roaring hit, but Audrey Hepburn in the title role was the event of the season. She also shook Hollywood observers to the marrow.

After Audrey’s first appearance before a camera, Paramount director William Wyler said, “She was absolutely delicious.”

A top Paramount executive agreed with him, adding, “We were fascinated.”

And so striking was her impact, after “Roman Holiday,” that Billy Wilder was moved to observe: “This girl, singlehanded, may make bosoms a thing of the past.”

Audrey Hepburn, however, the twenty-seven-year-old cosmopolite, who looks like every girl and like no girl (“She doesn’t even look like Audrey Hepburn,” a friend once remarked), is not inclined to ponder her own stature.

“Now and then,” she did concede one day recently, “it staggers you a little. So many people pointing cameras, especially in Europe. And now and then, you find yourself out of your depth. The questions—all the way from what do I think of love or how does it feel to be a star, to enormous ones, even political, with as many prongs as a pitchfork. Here I am, an innocent little actress trying to do a job, and it seems that my opinion on policy in the Middle East is worth something. I don’t say I don’t have an opinion, but I doubt its worth.”

Making “Funny Face,” Audrey Hepburn was a busy girl. Dancing with Fred Astaire is not for idlers. But Audrey loved every minute of it. The ballerina, bit appears, was not wasted.

Nor have her years of searching bee in vain. At one time, according to intimates, Audrey was extremely shy. Now she is gay and more confident.

Once, after her name had gone up in New York lights over “Gigi,” Audrey gazed at the marquee like a little girl. Then suddenly she said: “Oh, dear, and I still have to learn how to act.” If she has such misgivings now, she doesn’t mention them.

Audrey is by no means brash, and the little girl aura is still a part of her. But it’s quite plain to see that Audrey Hepburn has come to terms with herself.

In what can be loosely called the old days, Audrey Hepburn would go home to her apartment after work, still in a state of nervous concentration. She would be alone, and she would want it to be tomorrow, because her work was her fulfillment. And when she stopped and was alone again, there would be a sense of desolation and, occasionally, even a feeling of fright.

But now on this sunny day, she was going to wind up the afternoon and point her car west toward the sea, then north to Malibu. If she got there early enough, she would do the shopping. Then—home. Mel would be waiting there, he and the beach house and the sea. There was no need to wish for tomorrow, because the missing parts have fallen into place. The search for Audrey Hepburn is over. At least, for now. . . .

THE END

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE SEPTEMBER 1956