Alas, He’s No Hero To His Cat

In Southern California, it is the custom for enterprising real-estate fellows to bulldoze shelves into the perpendicular hills, slap houses and sometimes swimming pools onto the shelves, build perpendicular driveways leading thereto, and then grab for the nearest movie star. It is a highly successful business.

And on one of these shelves in a section called Sherman Oaks, in a house whose architecture he characterizes as Early Nothing, lives a man who would like to be George Nader.

It is a Walter Mitty-ish situation, since this man, despite the evident advantages of being handsome, pleasant and solvent, is by his own admission a long way from his goal. As most film-goers are well aware, George Nader is a swashbuckling chap who, on the screen, always says and does the right thing at the right time.

The Mitty of Sherman Oaks, on the other hand, misdials telephone numbers, has extraordinarily bad luck “seating” ladies at dinner tables, and on occasion runs out of conversational fodder after he’s taken the weather apart.

AUDIO BOOK

Again, when George Nader, umpty-nine feet of awesome manhood on the nation’s screens, wishes to dash down a flight of stairs, lunge into the back seat of a taxi and say, “Follow that cab!” there’s always a taxi waiting. If off-screen Nader tried the same thing, he’d undoubtedly be told by the doorman that the nearest hack was three blocks away.

Nor does our hero doubt that if the screen’s George Nader wanted to sing a love ballad to his best girl in the middle of a dance floor, the orchestra would just cue in with him, whereas if this Mitty fellow attempted any such hijinks, he would be frog-walked out of there on a charge of being drunk and disorderly.

All in all, there is only one notable resemblance between our man and George Nader. They have the same name. Purists might even argue they are the same person, but the George Nader of Sherman Oaks won’t buy any of that.

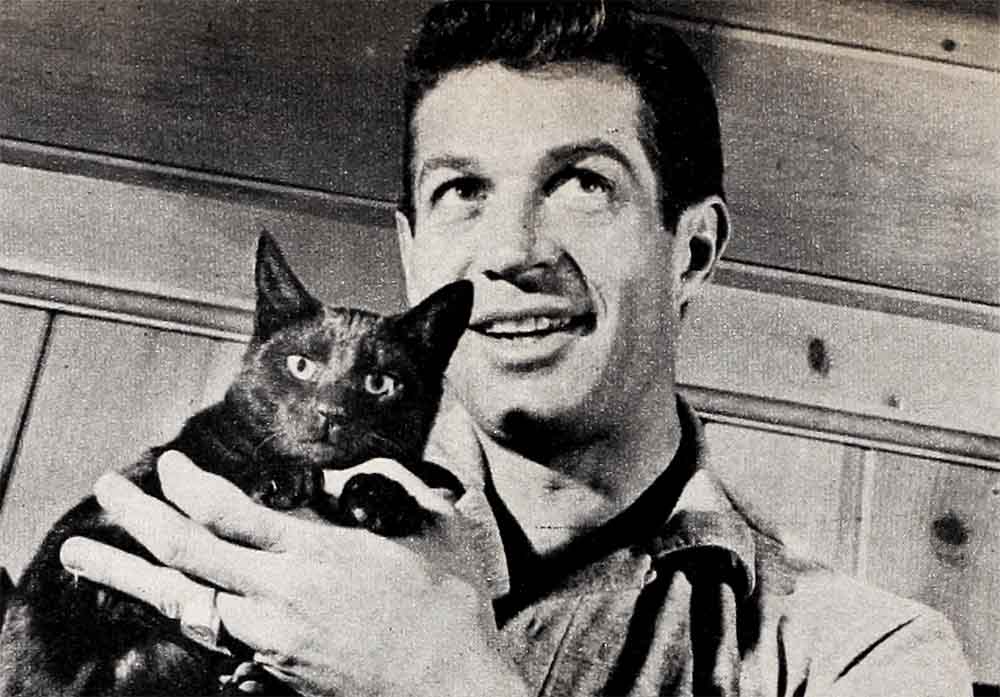

“It is,” he said on a recent afternoon, “a snare and a delusion. I have watched this Nader bucko in screening rooms and theatres. He has yet to trip over a chair or drop an ice cube down the love of his life’s back. He never dials a wrong number. And when the time comes for the girl to fail into his arms, she falls. Or at least sways. What all this has to do with me is impossible to say, but I do envy him. Give me another fifty years and maybe I’ll be George Nader. Meanwhile, I’m going to stumble around on my hillside and trip over the cat when I go to the refrigerator. And in a way, I don’t really mind. I feel a lot closer to that guy than I do to this Nader. The screen Nader’s a stranger to me.”

In fact, Nader did have a serious point to make, although he disguised it fairly well.

“I want to be careful how I say it,” he remarked thoughtfully. “This business I’m in—of illusion or dreams—is an honorable one. But people should try to realize this and not be carried away by the illusion. The image you and I have of George Nader is a skilled contrivance of writers and directors, sound men and cameramen. It’s not real life and, in my opinion, it shouldn’t be. But fantasy is fine only so long as it doesn’t drug people’s thinking.

“To give you a rather extreme example, let’s take Elvis Presley. When I went to the Orient to make ‘Joe Butterfly,’ I’d never heard of him. When I came back, I didn’t hear of anything else, and had to be checked out on him. Now whether he’s good, bad or indifferent, I can’t say. It’s not my field. But I do know he’s a promotion in the same way George Nader is—only to a greater degree. It’s an intelligent promotion, but my point is this: The emotional extravagance lavished on him is disturbing, like almost any other emotional extravagance. Or so I think.

“Things can go hogwild, at times. A few months ago, while I was away, mind you, an article appeared quoting me as to the kind of wife I’d like.” Nader turned slightly pale under his surprisingly deep tan; he’s a beach boy by avocation. Perspiration made a thin film on his forehead. “Holy cow! In the first place, it would be effrontery on my part to make such a statement. It’s an infringement on women’s individuality. In the second, it’s a point on which I have no clear notion. But the mail was waiting for me just the same. A lot of it was cute but a certain percentage was the sort that would have alarmed parents. And rightly so. It was really disturbing. Now consider Presley and what must happen to him. and you get a better idea of what I’m trying to say.

“These girls simply weren’t writing to me. They were writing to that guy on the screen who is big as Goliath and never trips over a cat. My unattainable ideal. But as remote from me as he is from them.”

The cheerful bachelor who does trip over the cat lives in his Early Nothing house—it is handsomer inside than out—bordered by cliffs on the south going up and cliffs on the north going down. He is fairly inaccessible both by virtue of a driveway that none but the most zealous autograph seeker would tackle, and a gate across the driveway which operates from the house. He lives alone but he is not lonely; he would seem to be one of those who prefers aloneness as a free and untrammeled base from which to operate. He dates frequently but never, he says, for the sake of publicity.

“It may sound to you like eyewash,” he told a friend recently, “but there are plenty of things I wouldn’t do to advance my so-called career by an inch or a mile, and one of them’s to date a girl I didn’t like. I date them in and out of the profession, but never for publicity reasons. There’s not a studio alive that could make me do that, including my own, Universal-International. I’m a quarter German, a quarter English, a quarter Scottish, and a quarter Irish, which makes me four times as stubborn as the normal man, and I’m just not going out to be seen. Besides, parties are more fun right here at home. Everybody can roll down the drive for the payoff. Also, I don’t get around much in Hollywood because I’m a dull son-of-a-gun and I don’t feel any great need to. But if you ever read about my being with this girl or that, star or unknown, it’ll be because I called her without any outside pressures from anyone.”

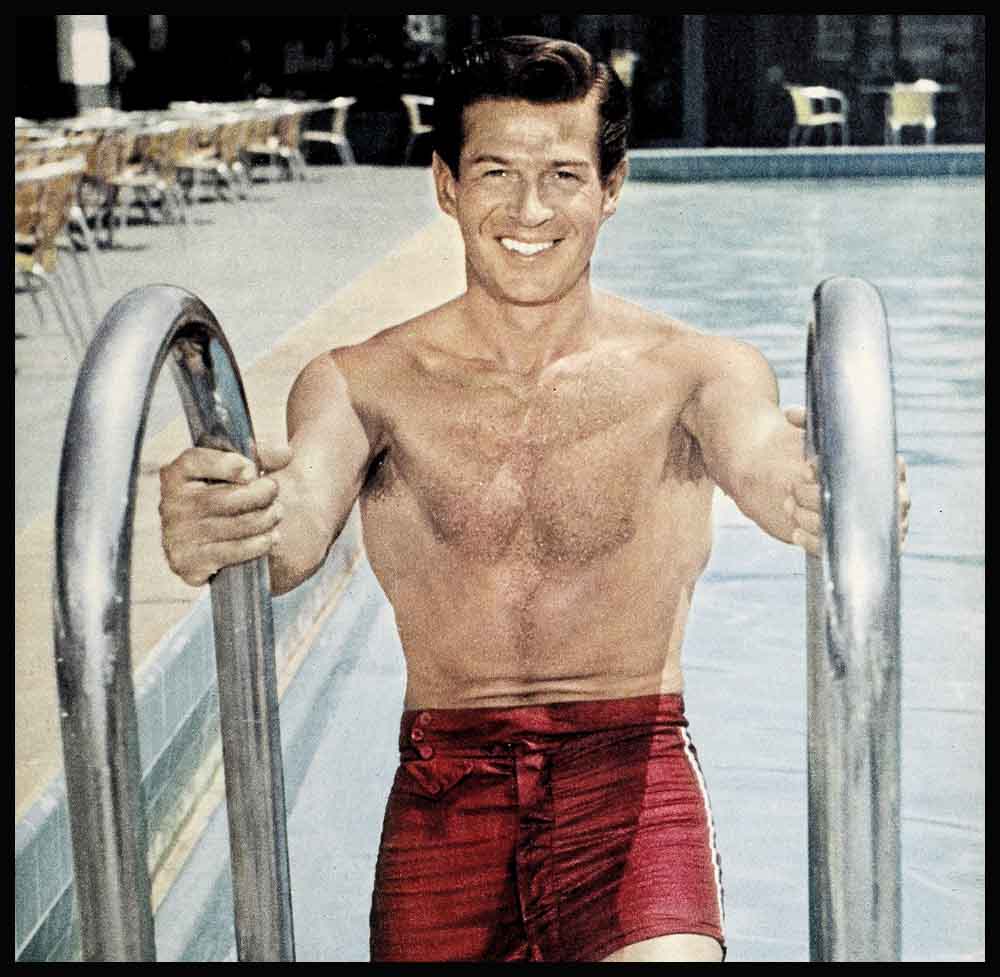

One enters the Nader house through the kitchen—very few stars can make that claim—and proceeds to a pleasant, sunny room with scatter rugs and big windows. The modest pool is just outside and a sheer cliff rises behind. The livestock includes a boxer dog as well as the cat.

Nader gets up early, whether he is or isn’t working. If he is working, he gets up very early. Otherwise, it’s around eight. Occasionally he shocks himself by breakfasting on fried pork chops. He swims a great deal and, when the pool strikes him as being of claustrophobic dimensions, drives to his beloved beach, where he lifts weights until his conscience is appeased. He likes girls as girls and women as women.

When boredom descends on him, he takes to the telephone, but he hates to answer it. Indeed, the sound of it freezes him, and sometimes he exerts a mighty effort of will to let it ring, but psychological necessity always wins out. There are not many people living who can let a phone ring.

Nader looks younger off the screen than on. It is rule of thumb that all actors look younger, all actresses smaller. He reads a great deal of Science fiction for relaxation, and a great deal of mutinous Philip Wylie when he wants to get his blood churning and his hair to stand on end. Wylie, an author of spectacular antipathies, detests mother love among other things, but this should not be attributed by inference to Nader. He is in favor of it.

It must be pretty well known by now that George Nader made it from Pasadena to Hollywood the hard way—or at least the long way—via India, Sweden and Germany, about 30,000 miles all told. In India, he played opposite Ursula Thiess, now Mrs. Robert Taylor, in “Monsoon”; in Sweden with Anita Bjork in “Memory of Love,” and in Germany with Anne Baxter and Steve Cochran in “Carnival Story.”

Interludes included an honorable Navy stint in World War II and Hollywood television. Now he has a string of U-I films running, the latest of which is “Man Afraid,” co-starring Tim Hovey, a child actor. Nader’s courage is such that this circumstance does not frighten him. To play opposite children is for any actor a kind of purgatory, but Nader does not care.

All that frightens him at the moment, and it cannot be overemphasized, is the public tendency to confuse the burnished symmetry of drama and motion pictures with the aimless and sometimes comic and sometimes cruel chaos of life.

“The contrast may depress people,” he said not long ago. “I know sometimes it depresses me. But I know me. I don’t fool myself. Say this big bucko, this Nader, this actor, say he’s a cowboy. A hero, of course, and he’s standing at the bar drinking buttermilk. A heavy comes in through the swinging door and draws. But Nader sees him in the mirror, flashes around and shoots the varmint’s gun out of his hand. But me, if I were doing it, I wouldn’t even be looking in the mirror. Or if I were, the gun’d get caught in my key ring and he’d shoot me six times through the stomach before I knew which way was up. See what I mean?

“Or the scene calls for Nader, black tie and all, to ‘seat’ the lady. Stand behind the chair, you know, and ease her into the table. In pictures, it’s easy. You see a shot of Nader taking the proper stance. In the next take, the lady’s in. That’s gypping. In my own case, I stand behind the chair and she sits down. Where are we now? Still two feet from the table. You have a choice. You can pick her up bodily and throw her at the table, which is not gentlemanly. Or she can rise slightly, in a kind of crouch, and squiggle her way in, pulling the chair behind her, while you continue holding it back, more of a hindrance than a help. I admit it does my morale good to watch George Nader on the screen but it doesn’t make me any less Walter Mitty.

“Or love conquers all. In pictures, yes. Practically always. It’s easy as long as the writers are behind you. But in life you haven’t got any writers. You play it by ear and hope your ear’s not defective.”

Nader professes many artistic reverences—Wylie, Rachmaninoff, Barbara Stanwyck, Loretta Young, William Holden, Greta Garbo, et al, plus the man who first creamed corn—but denies any special attachment. He does not deny it vigorously. He even denies it rather wanly like a man wary of going out on a limb. But he does deny it. Most frequently mentioned with him is a young actress named Dani Crayne, who’s pretty nice mentioning.

However, an associate says of him, “George is thirty-five, and may have made up his mind by now that bachelorhood’s what he prefers. He really rolls in it, you know. Freedom of action’s a fetish with him, and particularly the freedom to do nothing if he feels like it. Also, I’d say aloneness is an integral part of him. Not ‘loneliness’—I doubt that he’s ever lonely. There are people who just prefer the State of being by themselves whenever and however they like, even if their natures are social otherwise, and George strikes me as one of them. He’s as social a guy as you could know, when he’s social. But the idea of running in tandem through legal compulsion may irk him. I don’t know it, I’m just guessing. But I think it’s a pretty good guess. He tells you about that bugaboo of his? About refusing dates made by the publicity department? Well, there’s your answer. He doesn’t mind—but he wants to do the calling.”

The speaker is quite close to Nader. Hollywood, which is not especially close to him, prefers to reason it’ll be a quick Vegas deal whenever the right bride comes along, generally on the idea that George has bottled up a latent domesticity too long. Nader himself is so remote on the subject, it is next to impossible to say.

Of course, it is inevitable that George Nader, the screen hero, that is, would meet someone’s eyes in a medium shot across a crowded room and wind up a few reels later ducking rice or wandering into a sunset. But the truth is that anyone wandering into a sunset from the hillside home of George Nader, the ordinary Citizen, would stand a fine chance of falling down the cliff and breaking his neck—and two people could hardly escape it. It may yet come to pass, but only when the Walter Mitty of Sherman Oaks learns his lessons from George Nader, the man he would wistfully pattern his life after. And that, as he already has stated, may take fifty years.

THE END

LOOK FOR: George Nader in Universal-International’s “Four Girls in Town,” “Joe Butterfly” and “Man Afraid.”

It is a quote. PHOTOPLAY MAGAZINE APRIL 1957

AUDIO BOOK